Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Acta Obstétrica e Ginecológica Portuguesa

versão impressa ISSN 1646-5830

Acta Obstet Ginecol Port vol.14 no.3 Coimbra set. 2020

CASE REPORT/CASO CLÍNICO

In utero diagnosis of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Diagnóstico pré-natal de Doença Renal Poliquística Autossómica Dominante

Margarida Cal1, Iolanda Godinho2, Mariana Soeiro e Sá3, Margarida Cunha4, Rui Marques de Carvalho5

Departamento de Obstetrícia, Ginecologia e Medicina da ReproduçãoCentro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte - Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisboa, Portugal

1 Interna de Formação Específica de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. Departamento de Obstetrícia, Ginecologia e Medicina da Reprodução, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte - Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisboa, Portugal

2 Assistente Hospitalar de Nefrologia, Divisão de Nefrologia e Transplantação Renal, Departamento de Medicina, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte - Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisboa, Portugal

3 Assistente Hospitalar de Genética Médica, Divisão de Genética Médica, Departamento de Pediatria, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte, Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisboa, Portugal

4 Interna da Formação Específica de Pediatria, Departamento de Pediatria, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte - Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisboa, Portugal

5 Assistente Hospitalar Graduado de Obstetrícia e Ginecologia, Departamento de Obstetrícia, Ginecologia e Medicina da Reprodução, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte - Hospital de Santa

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited renal disease; its diagnosis, which used to be made during adulthood, has shifted towards earlier ages due to the development and widespread use of ultrasonography. Very-early onset (VEO) cases represent a high-risk group of patients. We describe a case of prenatal diagnosis in a pregnant woman with ADPKD. This case shows how diagnosis of ADPKD through ultrasound may signal high-risk patients that may benefit from early and timely treatment.

Keywords: ADPKD; In utero diagnosis; VEO; Ultrasound; Preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

Introduction

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited renal disease, with an estimated incidence of 1:1000 to 1:500 live births, affecting 12 million people worldwide1,2. Two genes have been identified: PKD1, located on chromosome 16 (16p13.3) and PKD2, on chromosome 4 (4q22.1), responsible for 85% and 15% of cases, respectively3. It is a systemic disorder characterized by bilateral progressive cystic dilatation and enlargement of the kidneys. It is associated with various extrarenal manifestations, such as hepatic and pancreatic cysts, intracranial aneurysms, mitral valve prolapse and colonic diverticula. ADPKD is a prominent cause of chronic kidney disease worldwide, accounting for approximately 5% of the total population with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)[1]. Progression to ESRD typically occurs within the fifth or sixth decades of life for PKD1 and seventh or eighth decades for PKD2 (median 54 years vs 74 years)4. While the majority of patients are diagnosed in adulthood, diagnosis at earlier ages or in utero has increased, mainly due to the development of ultrasonography and other renal imaging techniques [1]. Cases diagnosed either in utero or within the first 18 months of life are considered very-early onset (VEO) disease cases 1. VEO-ADPKD patients are more likely to have hypertension, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and larger age-adjusted kidney volume by ultrasound5.

Case presentation

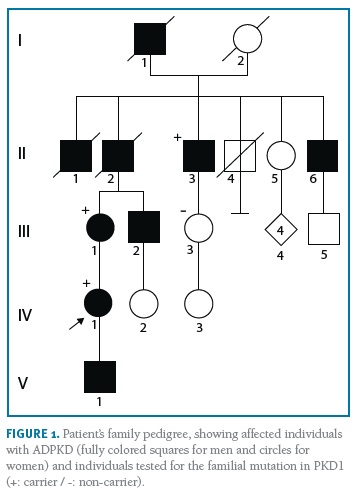

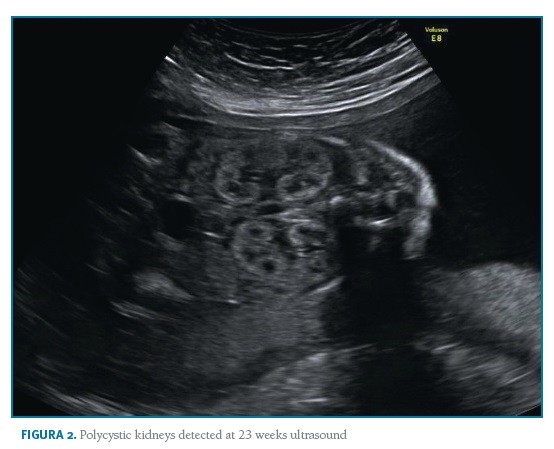

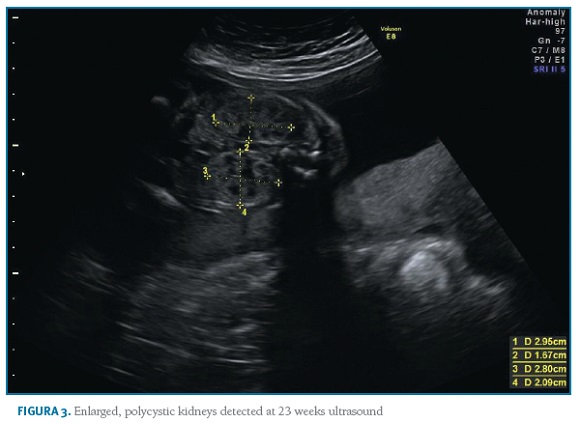

A 35-year-old nulliparous woman with ADPKD presented to a preconception appointment of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at our hospital. She had a familiar history of ADPKD (Figure 1) and her renal and hepatic ultrasound showed multiples cysts. Renal function was normal (serum creatinine 0.5mg/dL) and bland urinary sediment showed no proteinuria. She was normotensive and had no history of medication, alcohol or tobacco consumption. The patient was counselled about the risks, referred to Nephrology and Genetics clinics, and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) was suggested. She underwent genetic testing through complete sequencing of coding and intronic flanking regions of PKD1 and PKD2 on peripheral blood, which identified a heterozygous variant, c.6533_6541del (p.Cys2178_Thr2180del) in PKD1. No mutations were detected in PKD2. This variant, previously unreported, results in an in-frame deletion of 9 nucleotides and was originally considered as a variant of unknown significance. To help clarify its significance, familial segregation analysis was performed. The results revealed the presence of this variant on patient’s affected mother and maternal great-uncle, thus confirming its segregation with the phenotype and confirming its pathogenicity. Considering the 50% transmission risk to her offspring, PGD was discussed with the couple with further referral to specialized clinics. However, the patient had a spontaneous pregnancy meanwhile, and initiated a regular Obstetric surveillance. First trimester screening revealed a low-risk combined screening and no ultrasound abnormalities. Morphologic ultrasound performed at 21 weeks and confirmed at 23 weeks showed a male fetus with bilaterally enlarged polycystic kidneys and normal corticomedullary differentiation (Figures 2 and 3).

All other morphologic features were normal, including amniotic fluid volume. The couple was informed and counselled regarding prognosis in a multidisciplinary setting involving Obstetrics, Genetics, Adult and Paediatric Nephrology. Based on family history, invasive prenatal diagnosis was suggested to confirm the diagnostic hypothesis of in utero presentation of ADPKD, but the couple declined it. The 30 weeks ultrasound displayed comparable renal cysts dimensions, 44th growth percentile and normal blood flow. On 35 weeks ultrasound, the growth curve dropped to 8th percentile, with normal doppler of median cerebral artery, umbilical artery and cerebroplacental ratio (CPR). When doppler blood flow analysis was repeated one week later, it showed blood flow redistribution with CPR suggestive of centralization and fetal growth restriction (FGR). Labour was induced at 37 weeks according to institutional protocols. Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery was performed due to labour dystocia. The baby was born weighting 2490g with an Apgar score of 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 minutes after birth. There was no evidence of enlarged kidneys both on inspection or palpation and renal function was normal. There were no complications during the first days of life and both mother and baby were discharged home after five days, with follow-up at the paediatric nephrology clinic. Genetic testing of the newborn confirmed he was a carrier of the same familial variant identified in the mother.

Discussion

ADPKD is the most common inherited renal disease, with an estimated incidence of 1:500 to 1:1000 live births. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant disease with virtually complete penetrance and variable expressivity. PKD1 and PKD2 genes code for poly-cystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively, proteins localized on primary cilia that interact to form a complex important in renal tubular cell differentiation and maintenance. Loss-of-function mutations in PKD1 and PKD2 are responsible for defects in primary cilia, leading to progressive bilateral formation of cortical and medullary renal cysts6. While the majority of patients are diagnosed in adulthood, diagnosis in earlier ages has increased due to development of ultrasonography and other renal imaging techniques [1]. ADPKD is associated with increased rates of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, but it shows no association with fetal complications7. ADPKD is a significant entity in childhood with wide clinical presentation spectrum; histological or genetic analysis is necessary to differentiate it from Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease. There is a remarkable inter and intra-familial variability concerning progression of ADPKD. It can present as early as in utero, but ESRD typically occurs in late middle age. Kidney and cyst volumes are the strongest predictors of renal functional decline8. Other risk factors for progression to ESRD include truncated PKD1 mutations, black race, diagnosis or first episode of haematuria before age 30, onset of hypertension before age 35 and sickle cell trait9. PKD2-mutated cases tend to have later onset and milder clinical disease. Children diagnosed either in utero or within the first 18 months of life are considered to have very-early onset disease and represent a particularly high-risk group10. Two studies, by Shamshirsaz et al. and Nowak et al. found a greater hazard of adverse clinical outcomes in VEO-group, associated with development of hypertension and progression to ESRD14. Due to the highly variable presentation of ADPKD, it is extremely important to perform careful risk stratification in order to identify high-risk patients who will benefit from early intervention1,10. Blockade of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and reduction in blood pressure level showed potential for reducing renal growth and left ventricular mass and may be promising drugs11,12. Lifestyle and dietary changes are suggested to all patients and recent studies support a role of statins for early treatment of ADPKD in children and young adults13. Tolvaptan, a vasopressin receptor antagonist, is capable of slowing the rate of renal function decline in adults with eGFR>25ml/min/1.73/m2.14,15 Clinical trials concerning Tolvaptan for children with ADPKD [Tolvaptan (NCT02964273)] are underway. A number of new agents are currently being tested in clinical trials and waiting approval16. Tesevatinib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, is currently undergoing testing in a phase-2 clinical trial for ADPKD (NCT02616055) and in phase-1 trial for autossomic recessive polycystic disease (ARPKD). The interaction between genes, proteins, and overlapping cystic phenotypes suggests that therapeutic interventions and lessons learned from clinical trials in ADPKD can be applied to both patients with ADPKD/ARPKD17. However, there is limited evidence about long-term prognosis of these patients and it remains difficult to provide parents with evidence-based genetic counselling. For future parents in preconception stage, as for other monogenic diseases, the option of PGD allows testing the embryo for ADPKD-mutations, while pregnancy success rates are dependent on the assisted reproductive technology.

REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

1. Shamshirsaz A, Bekheirnia RM, Kamgar M, Johnson AM, Mcfann K, Cadnapaphornchai M, et al. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in infancy and childhood: Progression and outcome. Kidney Int. 2005; 68(5):2218-2224 [ Links ]

2. Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1287-1301 [ Links ]

3. Peters DJ, Spruit L, Saris JJ, Ravine D, Sandkuijl LA, Fossdal R, et al. Chromosome 4 localization of a second gene for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 1993;5:359-362 [ Links ]

4. Reddy BV, Chapman AB. The spectrum of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(1):31-42 [ Links ]

5. Harris P, Bae K, Rossetti S, Torres V, Grantham J, Chapman AB, et al. Cyst number but not the rate of cystic growth is associated with the mutated gene in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(11):3013-9. [ Links ]

6. Boyer O, Gagnadoux MF, Guest G, Biebuyck N, Charbit M, Salomon R et al. Prognosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease diagnosed in utero or at birth. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:380-388 [ Links ]

7. Nowak KL, Cadnapaphornchai MA, Chonchol MB, Schrier RW, Gitomer B. Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Very-Early Onset Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:171-178 [ Links ]

8. Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1533-43 [ Links ]

9. Boyer O, Gagnadoux MF, Guest G, Biebuyck N, Charbit M, Salomon R, Niaudet P. Prognosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease diagnosed in utero or at birth. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:380-388 [ Links ]

10. Wu M, Wang D, Zand L, Harris P, White W, Garovic V, Kermott C. Pregnancy Outcomes in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: a Case-Control Study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:807-812 [ Links ]

11. Chapman AB, Bost JE, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford L, Bae KT, Landsittel D, et al. Kidney volume and functional outcomes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):479-86 [ Links ]

12. Corradi V, Gastaldon F, Caprara C, Giuliani A, Martino F, Ferrari F, et al. Predictors of rapid disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Minerva Med. 2017;108(1):43-56. [ Links ]

13. Nowak KL, Cadnapaphornchai MA, Chonchol MB, Schrier RW, Gitomer B. Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Very-Early Onset Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:171-178 [ Links ]

14. Schrier RW, Shamshirsaz AA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Nephrol Hypertens. 2004;10:49-55 [ Links ]

15. Grantham JJ. Rationale for early treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:1053-1062 [ Links ]

16. Cadnapaphornchai MA, George DM, McFann K, Wang W, Gitomer B, Strain JD, et al. Effect of pravastatin on total kidney volume, left ventricular mass index, and microalbuminuria in pediatric autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:889-896 [ Links ]

17. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25): 2407-2418 [ Links ]

18. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Perrone RD, Koch G, et al. Tolvaptan in Later-Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1930-1942 [ Links ]

19. Riella C, Czarnecki PG, Steinman TI. Therapeutic advances in the treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;28(3-4):297-302 [ Links ]

20. Sweeney WE, Avner ED. Emerging Therapies for Childhood Polycystic Kidney Disease. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:77 [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Margarida Cal

Hospital de Santa Maria

E-Mail: margarida.cal@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency

Author contribution

All authors equally contributed to the conception of this work and were involved in critical discussion, drafting and revision of the manuscript and contributed to the final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Recebido em: 04/05/2020. Aceite para publicação: 06/07/2020.