Introduction

Ovarian carcinoma is the most lethal gynecological cancer1. Standardized ovarian cancer incidence rate for a Portuguese population is 9.5 / 100.00 women2. 90% of all ovarian cancers are epithelial and among these 16-25% are endometrioid carcinomas3. About 15-20% of endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary are synchronized with an endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium4. A distinction between metastasis and primary cancer has prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Endometrioide ovarian tumor and endometrial carcinoma type I share clinical features such as perimenopause age, early stages, low degrees of differentiation or with more favorable prognoses5. They also present similar molecular changes such as microsatellite instability, P53 mutation, nuclear b-catetin expression and mutations of the ARID1A, PTEN, KRAS and PIK3CA4 genes5.

Although the etiology and pathology of synchronous ovary and endometrium tumor are unclear, it has been postulated that similar tissues when simultaneously exposed to a common carcinogen or molecular event, may develop synchronous neoplasms within a single preneoplasic field6. Endometrioid hystology is relatively rare among ovarian carcinomas and it has been reported to be associated with the same risk factors as endometrioid carcinomas of the endometrium6. Endometriosis may contribute to its etiology6-8. Two theories support this relation: (1) a potential direct malignant transformation on endometriotic implants and (2) the idea that endometriosis and cancer share many predisposing factors (environmental, immunological, hormonal and genetic)7.

To highlight the clinical and genetic characteristics, management and prognosis of women with synchronous endometrial and ovarian carcinoma (SEOC), we report a case of a 49-year-old woman with endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium and synchronous endometrioid ovarian cancer. The authors requered prior approval by Ethics Committee of Instituto Português de Ginecologia Francisco Gentil de Coimbra and request informed consent from the respective patient.

Case Description

We report a case of a 49-year-old female patient (gravida 1, para 1) who presented with abnormal uterine bleeding with 6 months of evolution. During gynaecological examination, a large mass was identified in the right adnexal region. The parametrium were free on physical examination. In the endovaginal ultrasonography, a large, irregular, multilocular-solid cystic, right adnexal mass measuring 17x15x11cm and an endometrial thickness of 31mm was visualized. Serum CA 125 concentration was 466 U/mL (normal range <35 U/mL). Others tumor markers such as Carcinoembryonic Antigen e Human Epididymis Protein 4 were in normal range. According to the IOTA simple rules9 the cyst was classified as malignant, because it has one malign feature (irregular multilocular-solid cyst with largest diameter ≥ 10cm) and no benign features. IOTA - Adnex Model revealed 43.4% of malignancy risk.

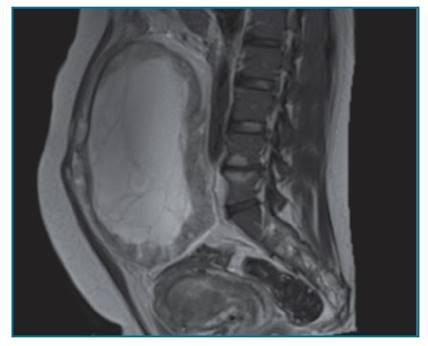

An endometrial biopsy guided by hysteroscopy was performed that revealed an endometrioid G2 endometrial carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging identified a large complex pelvic mass, predominantly cystic, but with an extensive peripheral solid component, measuring about 20x19x10cm, likely originating in the right ovary, suggestive of malignant epithelial neoplasia. Distending the endometrial cavity, a lesion suggestive of neoplasm confined to the body of the uterus was observed, which does not appear to invade the myometrium or the cervical stroma (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Magnetic Resonance: Magnetic resonance imaging showing a large complex pelvic mass, predominantly cystic, but with an extensive peripheral solid component, measuring about 20x19x10cm, likely originating in the right ovary, suggestive of malignant epithelial neoplasia. Distending the endometrial cavity, it is possible to identify a lesion suggestive of neoplasm confined to the body of the uterus, which does not appear to invade the myometrium or the cervical stroma.

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. During inspection it was identified a large ovoid right ovarian mass 20x19x10cm, with a predominantly smooth, pink surface, on one side with multiple nodular formations varying between 2 and 5 cm of major axis with brownish areas. The uterus was normal-sized, covered with smooth and pink serosa. The left ovarian and tubes were macroscopically normal. On the anterior edge of vagina, a brownish nodule with a larger diameter of 3.5 cm was seen. No other lesions were identified in the abdominal cavity. Standard cancer staging surgery was performed with collection of ascitic fluid, total hysterectomy, bilateral anexectomy, infracolic omentectomy, para-aortic lymphadenectomy (6 lymph nodes) and bilateral pelvic (11 left and 9 right lymph nodes), Douglas fundus biopsy and an excision of a nodule on the anterior broadside of the vagina. The patient underwent ovarian intraoperative evaluation. Two frozen sections were made: one of the ovarian surface (that was focally involved), and the other of the inner of the ovarian (that was extensively necrosed). The result of the intraoperative evaluation showed glandular proliferation of endometrioid and mucinous glands, with atypia suggesting Borderline tumor.

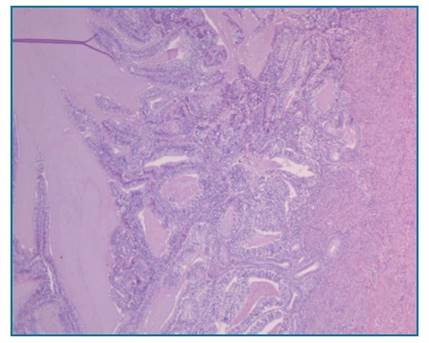

Figure 2 H.E. x 5 - Endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Endometrial cavity containing malignant glandular proliferation, showing confluent glandular growth with loss of intervening stroma, invading the inner half of the myometrium (which is present in the photo’s right side); the glands are lined by pseudostratified / stratified atypical epithelium. No lymphovascular invasion was identified.

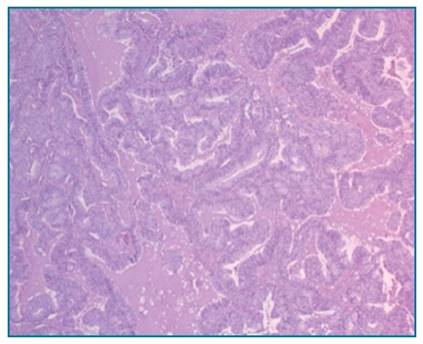

The final histological report confirmed a endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium staged as FIGO IA, G2, R0 (Figure 2). In addition, a synchronous right ovary endometrioid carcinoma was identified staged as FIGO IC2, G2, R0 (Figure 3). Peritoneal

fluid cytology and all biopsies, as well as lymph nodes were negative for malignant cells.

FIGURE 3 H.E.x10 - Right Ovaric endometrioid carcinoma. Confluent glandular growth with loss of intervening stroma; the glands are lined by pseudostratified / stratified atypical epithelium. No lymphovascular invasion was identified. The left ovary was normal.

The patient had no family history of colon, endometrial, breast or ovarian cancer. Hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer syndrome assessment by immunohistochemistry was performed and showed no microsatellite instability the MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2 proteins.

No adjuvant therapy was administered. Follow-up with regular clinical gynecological examinations and measure of Ca 125 was recommended. The patient has been asymptomatic and shows no evidence of local recurrence or systemic disease after 3 years of clinical surveillance.

Discussion

Simultaneous diagnosis of endometrium and ovarian carcinoma represents an uncommon event. According to multiple studies, 10% of women with ovarian cancer have SEOC and about 5% of women with endometrial cancer are diagnosed with SEOC8. The majority of women with SEOC are 41-54 years old, 40% of them are nulliparous, two thirds of them are premenopausal, and one third are obese10. Dogan in 2017 affirmed when managing young women with endometrial cancer, treating physicians should be aware that some of them will have synchronous ovarian cancer11. The most common symptom of SEOC is abnormal uterine bleeding, but some patients present in gynecological clinic due to pelvic pain or for a palpable pelvic mass12. In this case, we report a premenopausal woman with abnormal uterin bleeding and a palpable pelvic mass.

A final diagnosis of synchronous ovarian and endometrial cancer requires ruling out two other possible diagnoses: primary endometrial cancer with ovarian metastasis or primary ovarian cancer with endometrial metastasis12. In the past, pathologic criteria by Ulbright and Roth12 were used in order to distinguish synchronous primary tumors from metastasis. These criteria were revised in 1998 by Scully et al13. Since then, several authors have proposed methods for molecular analysis, but no consensus has been reached yet13,14. SEOCs are characterized by histological dissimilarity of the tumors, no or only superficial myometrial invasion of endometrial cancer, no vascular space invasion of endometrial and ovarian tumor, absence of other evidence of spread, ovarian unilateral tumor, ovarian tumor in the parenchyma and without involvement of the surface of the ovary, dissimilarity of molecular genetic or karyotypic abnormalities

in the tumors and different ploidy of DNA of the tumors13-15. Endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the endometrium typically express estrogen and progesterone receptors. Other frequently altered genes are KRAS, PTEN, and b-catenin16. A subset progress into high-grade carcinoma which is accompanied by loss of receptor expression and accumulation of TP53 mutations17. An accurate differential diagnosis between an ovarian metastasis and a second primary ovarian cancer is difficult. However, it is important to distinguish between these two entities because the correct diagnosis allows to differentiate patients in advanced stage who need adjuvant treatment from patients with SEOC diagnosed in early stage who do not benefit from this type of treatment18.

In this case report, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy. SEOC were diagnosed and treated in early stage with a good prognosis. The characteristics that support the diagnosis of two synchronous tumors are: similar size of both tumours, unilateral ovarian tumor, superficial invasion of the myometrium, no lymphovascular invasion identified, no involvement of the peritoneum, lymph nodes, fallopian tube. No adjuvant therapy was required. The patient has been asymptomatic and shows no evidence of local recurrence or systemic disease after 3 years of clinical surveillance.

An immunohistochemical analysis for mismatch repair proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) or microsatellite instability research should be performed4. Patients with MMR protein expression changes or microsatellite instability should be evaluated in a genetic consultation.4 In cases with normal expression of MMR proteins or with microsatellite stability, a genetic study is indicated when there is a suspicion of Lynch Syndrome, Cowden Syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome, POLE / POLD1-associated polyposis or other hereditary predisposition syndrome4.

The prognosis of women with SEOC is good based on a high proportion of early stage cases and favorable histologies12. Prognosis of women with SEOC seems to be the same in comparison with matched controls with either women with single ovarian or single endometrium cancer19. The mean recurrence-free survival time in women with SEOC was 1.9 years and the mean overall survival time was 4.0 years12.

In conclusion, although SEOC is a rare phenomenon, it is necessary to distinguish this type of malignancy from a metastatic disease. Molecular biomarkers are important in order to identify the characteristics and underlying pathogenesis of SEOC. The majority of the tumors are well differentiated and of endometrioid cell type with a good prognosis.