Introduction

Struma ovarii is a form of mature teratoma consisting predominantly of thyroid tissue1. It corresponds to about 5% of ovarian teratomas, with a peak incidence between 40-60 years old1. It represents 1% of ovarian tumors and approximately 3% of all dermoid tumors2.

Depending on its histological characteristics, it can be classified as benign or malignant and most of the time it presents with a unilateral adnexal mass3.

The symptoms are variable and may present with pain, abnormal uterine bleeding or pelvic mass in the gynecological examination, with a considerable percentage of asymptomatic patients, being the diagnosis incidentally made by ultrasound or other imaging exam3. In 5% of the cases, it may occur with ascites (20%) and pleural effusion, constituting the Pseudo-Meigs Syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by the presence of pleural effusion and ascites caused by a pelvic tumor other than a fibroma4,5.

Symptoms and analytical alterations of hyperthyroidism are uncommon, appearing in 5-8% of cases without anatomical changes of the thyroid gland1,3.

The serum marker cancer antigen-125 (CA-125) is used as a classic marker in the surveillance of women treated for epithelial ovarian carcinoma, however with poor specificity5. CA-125 elevation increases the suspicion of malignancy and it is described in some cases of malignant struma ovarii. Rarely, it is associated with Pseudo-Meigs Syndrome, being highly suggestive of malignancy4,5. This elevation can be explained by the irritation and subsequent inflammation of the pleura and peritoneum produced by the presence of fluids in these spaces6.

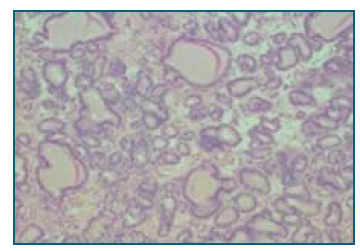

From the radiological point of view, it appears as a solid ovarian mass, without specific characteristics of this entity. The diagnosis is histological, with signs of malignancy being found in 5-37% of cases, being more frequent in large tumors7. The histological criteria for malignancy are the same as for other types of thyroid tumors1. The struma ovarii is composed by variably sized macro and microfollicles containing colloid8. Cells are flattened to cuboidal/columnar with small round to oval nuclei, even chromatin and pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm8. There are no histologic signs of malignancy such as papillary thyroid carcinoma (the most commonly associated malignancy in struma ovarii) cytologically characterized by crowded or overlapping elongated nuclei with irregular contours or chromatin clearing, and papillary architecture8. Follicular carcinoma is the second most common malignancy form in this tumor, and its histologic diagnosis implies the demonstration of tumor invasion trough capsule into surrounding ovarian tissue, vascular invasion or metastases1,9.

Metastasis is rare, occurring in 5% of cases, to the lung, bone, liver, and brain.

The treatment of malignant struma ovarii is not consensual and may involve bilateral oophorectomy, total hysterectomy, and adjuvant therapy1,3,10. In the benign form, the surgical tumor removal is sufficient for treatment3,10.

The prognosis is generally favorable, with a 5-year survival rate of 92-96.7%10. The prognostic factors associated with malignant disease are not entirely known, however, the lesion size and the histological subtype seem to have an impact on the survival1.

Clinical case

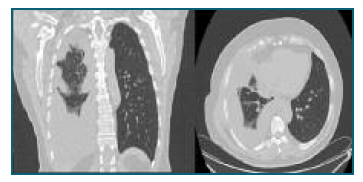

Female, 62 years old, with a personal history of arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and asthma, polymedicated. Multiparous, menopause at age 55, not having undergone hormone replacement therapy. Monitored in a Pulmonology consultation due to dyspnea for medium efforts with one year of evolution, with parapneumonic pleural effusion (Figures 1 and 2), requiring repeated thoracocentesis, with a negative cytological study. Pleural biopsy was performed, which was negative for malignancy. In this context, she underwent positron emission tomography (PET) which, in addition to a large pleural effusion, revealed the presence of ascitic fluid in the pelvis. The patient was referred to a Gynecology consultation to exclude a malignant gynecologic disease, not presenting changes in the gynecological examination.

Figure 1 and 2 Medium/large pleural effusion on the right, multiloculated at the bases. Thin layer of pleural effusion on the right.

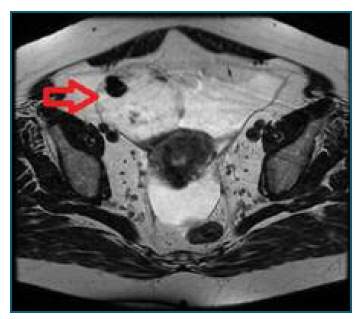

A transvaginal ultrasound was performed, which revealed a solid lesion of 70×54×28 mm, in the right ovarian, with peripheric increased vascularity on Doppler examination (score 3) and a slight ascitic effusion in the cul-de-sac. A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, confirming this finding with a description of a solid adnexal lesion measuring 75×60×30 mm, strongly enhancing contrast, with a low-uptake central region (Figure 3). In the analytical study performed, the patient had increased CA-125 (1475.8 U/ml - reference value of 35 U/ml) and normal thyroid function.

Figure 3 Solid right adnexal lesion in MRI, in an axial plane (red arrow). Lesion measuring 75×60×30 mm, solid, strong contrast uptake, with a low uptake central region.

Patient underwent exploratory laparotomy with collection of ascitic fluid and right adnexectomy, having the extemporaneous examination revealed a lesion compatible with struma ovarii. Total hysterectomy and left adnexectomy were performed, with no macroscopic residual disease at the end of the procedure.

The postoperative period was uneventful, with spontaneous resolution of the pulmonary condition.

Histological examination revealed an right ovary measuring 70×60×50 mm with a lesion with characteristics of struma ovarii without signs of malignancy (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Definitive histological examination in paraffin sections demonstrates an ovarian lesion with characteristics of struma ovarii, without signs of malignancy. H&E stain.

Observed in a Pulmonology consultation one month after gynecological surgery with complete resolution of the respiratory condition, having been discharged from the Pulmonology consultation. (Figure 5)

Figure 5 Chest radiography, 5 weeks after the surgical procedure, without signs of pleural effusion, spontaneous resolution.

Patient oriented to a Gynecology Oncology consultation for postoperative evaluation, with no complaints and no evidence of gynecological pathology and with normalization of CA-125 values.

Discussion

Struma ovarii is a rare form of mature teratoma consisting of more than 50% of thyroid tissue1. Most tumors are unilateral and benign, rarely appearing at menopause, with a peak incidence during childbearing age. They are mostly asymptomatic, being an imaging finding3. In the present case, the patient started with respiratory symptoms, being a diagnostic challenge, constituting the Pseudo-Meigs Syndrome. The pathophysiology of pleural effusion can be explained by the drainage of ascites through the diaphragm6. In this case, the pleural effusion and its characteristics became the pillar for the differential diagnosis of the patient’s pathology. The respiratory condition, despite multiple interventions, had spontaneous resolution after surgical removal of the teratoma.

Elevation of CA-125 increases the suspicion of malignancy in the study of adnexal masses and is described in about 5 to 37% of cases of struma ovarii7. Rarely, it is associated with Pseudo-Meigs Syndrome, being highly suggestive of malignancy4,5. This elevation can be explained by the irritation and subsequent inflammation of the pleura and peritoneum produced by the presence of fluids in these locals6. The patient had a considerable elevation of this marker, despite the benignity of the pathology, thus demonstrating its low specificity for malignancy.

Most of these tumors are functionally inactive, which is why symptoms and analytic changes of hyperthyroidism are uncommon. The patient under study never presented anatomical or analytical changes in thyroid function during her illness.

Imaging diagnostic suspicion is difficult, as it appears as a solid ovarian mass, without specific characteristics, and it is not easy to differentiate it from other types of ovarian tumor. In a postmenopausal woman, a solid mass with ascites and elevation of CA-125 should be assumed to be a high probability of malignancy and probably in an advanced stage. The patient had all these characteristics, with the hypothesis of ovarian cancer being the most likely. The diagnosis of struma ovarii is therefore histological, thyroid tissue is found on microscopic examination and the criteria for malignancy are the same as for other types of tumors of the gland1. Malignant transformation is described in 5-37% of cases7, being more frequent in large tumors (greater than 10 cm) and with more than 80% of stromal tissue11.

Treatment of malignant struma ovarii may involve bilateral oophorectomy, total hysterectomy and adjuvant therapy that may include radioactive iodine1,3. If benign, surgical treatment is sufficient3.

In this clinical case, the initial presentation with pleural effusion became a clinical challenge because the study was guided by the signs and symptoms presented by the patient, who did not present any gynecological complaints. Not being a frequent diagnosis in post-menopause, the atypical presentation made the diagnosis difficult. After surgery, the patient had spontaneous resolution of symptoms. In the presence of pleural effusion, pelvic mass, ascites and elevation of CA-125, although rare, it is possible to have a diagnosis of a benign situation.