Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ensuring the highest standard of health is a fundamental right of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition1. Likewise, the Portuguese Republic Constitution states in its 64th article that everyone has the right to health protection and the duty to defend and promote it2.

Moreover, healthcare should be adapted to communities according to their special needs, and mainly to each person in its specificity. In particular, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual/Transgender, Queer, Intersexual, Asexual and Others (LGBTQIA+) community presents specific and unique health needs, where Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) is of particular importance3. Nevertheless, there are some disparities in the literature among heterosexual and LGBTQIA+ people regarding the access to healthcare, mainly in the context of SRH, including contraception, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and cervical cancer screening4-8.

Previous negative experiences faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals in health services, particularly those related to sexuality and gender identity, are some of the barriers that could justify these inequalities, having been demonstrated in the study “Health in Equality” by Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Intervention (ILGA) Portugal4 and the European LGBTI 2020 Survey9 of the Agency for Fundamental Rights of the European Union. In the same way, the use of heteronormative language was also emphasized in the literature as a possible barrier to healthcare access. Both factors may contribute to decrease the interaction between LGBTQIA+ people and healthcare providers, thus impairing the quality of assistance to this community3.

On the other hand, the knowledge and awareness of health professionals about the LGBTQIA+ community and their needs are often inadequate and scarce. Indeed, many health professionals reported to feel unprepared or even uncomfortable to provide counselling and therapeutic guidance for this population. Furthermore, even though many health professionals know the meaning of the acronym LGBTQIA+, issues related to sexuality and gender identity still remain poorly understood and worked on3,4.

Frequently, sexual identity is confounded with sexual behavior, leading health professionals to presume that the majority of LGBTQIA+ people don’t need contraception, despite its non-contraceptive benefits that could be of interest in this particular community (menstrual avoiding or protection from STDs). In fact, evidence suggests that 1 in 3 sexual minority women seek contraceptive counseling. Nonetheless, it would be more likely that they use less effective contraceptive methods or no contraception than heterosexuals, which could explain the increase in unwanted pregnancy and STDs rates in this community3,5-7,10-12.

In fact, some studies have described the LGBTQIA+ point of view and the barriers faced in accessing healthcare4,8,9. However, there is actually insufficient published evidence regarding the perspective of healthcare providers and their main challenges in providing care to this community, particularly in the context of SRH.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to understand the perception of Gynecology/Obstetrics (G/O) and General Practice (GP) physicians in Portugal within the scope of providing SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people, evaluating their clinical experience, level of knowledge and training needs in this field. Additionally, we intend to evaluate whether these outcomes were affected by the physician’s individual factors like age, medical specialty, professional category, number of years in practice and region of the country where they work from.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment and survey development

In September 2021, we recruited physicians directly involved with SRH counseling, in particular of G/O and GP specialties, to complete a survey about their self-perception of knowledge and practices on SRH care to the LGBTQIA+ community. The survey link was shared online through the physician’s professional contacts, email addresses and social networks, involving the collaboration of the main national societies of both medical specialties. To be eligible for our study, the participants needed to currently work as a physician (resident or specialist) in G/O or GP and provide medical care in a public and/or private Portuguese healthcare institution.

The survey was only available in Portuguese and data were collected until April 2022 using Google Forms. Participants’ consent for the study was collected electronically. Participation was voluntary and not compensated, being blinded relative to physician identification, in order to guarantee the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants. All clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Clinical Research and Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra determined that a review board approval was not necessary to report the results of the survey.

The survey included a structured and customized questionnaire that was developed by the research team for this purpose. Before fielding the survey, four medical providers with relevant clinical expertise beta-tested the survey to ensure the content was clear and appropriate for the intended audience and that the skip logic worked appropriately.

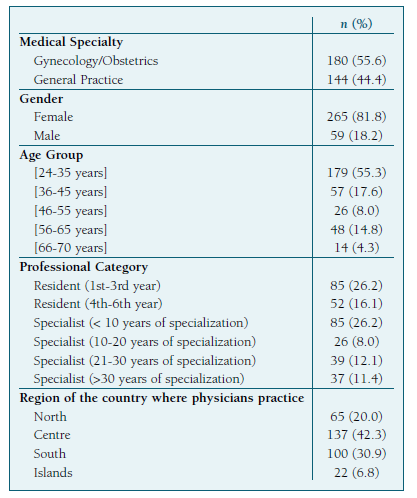

Sample characteristics

Overall, 324 physicians completed the survey, of which 55.6% were Gynecologists/Obstetricians and 44.4% were General Practitioners. Among participating physicians, over half (57.7%) were specialists, most of them (31.5%) with at least 10 years of specialized practice. The majority of respondents were female (81.8%) and over half (55.3%) were under 35 years of age. The professionals that work in the Centre and South regions of the country yielded the most responses (73.2%). The demographic characterization of the participants was summarized on Table I.

Survey instrument

The questionnaire comprised a small explanatory text indicating the goals of the study, followed by four groups of questions. The first group contained 5 questions aimed at sample characterization (physician age, gender, medical specialty, professional category/years of clinical practice and region of the country where they work from). The second group included 5 questions regarding practices and clinical experience on sexuality and gender identity. The third group had 10 questions focusing on the level of knowledge and experience of physicians concerning SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people. In this section, questions approaching the following issues were included: difficulties and barriers experienced by LGBTQIA+ patients in SRH care, reasons that motivate a LGBTQIA+ family planning consultation and physician’s preparation to perform this assignment, use of contraception and type of contraceptive methods, occurrence of unplanned pregnancies and existence of multiple partners. Finally, in the fourth group, a question to access the training needs in this field was considered, as well as other additional suggestions.

The questionnaire encompassed open and closed-ended questions, including dichotomous, multiple-choice and Likert scale types.

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out to characterize the study sample and assess the physician’s responses. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and analyzed considering the χ2 test. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed using STATA® software version 16.0.

Results

Clinical practice on sexuality and gender identity

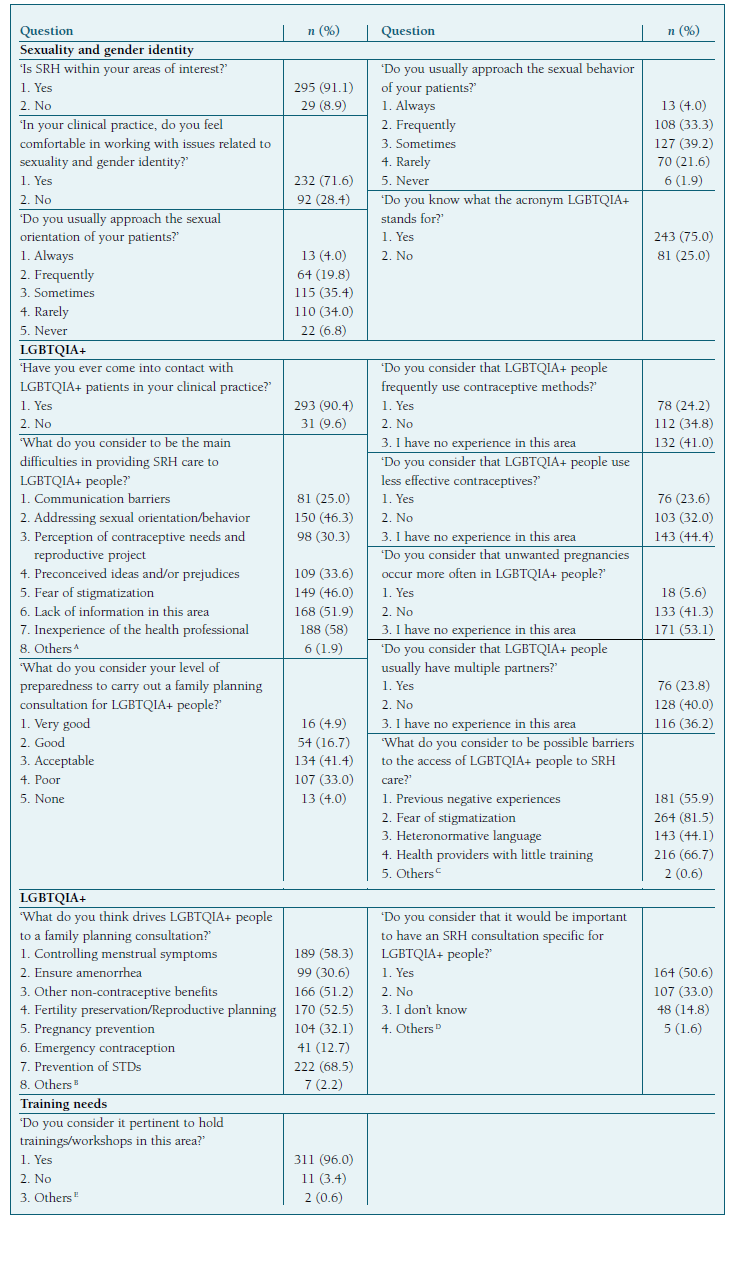

Most of the participants (91.1%) stated that SRH was within their areas of interest and the majority (71.6%) felt comfortable approaching issues related to sexuality and gender identity. Considering their practices, over half of the participants (69.4%) ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely’ address the sexual orientation of their patients, although the majority (72.5%) used to ‘frequently’ or ‘sometimes’ inquire their sexual behavior. Additionally, three-quarters of the respondents claimed to know the meaning of the acronym LGBTQIA+ (Table II).

Level of knowledge and experience on SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people

Most of physicians (90.4%) had contact with LGBTQIA+ individuals in their clinical practice. Health professional’s inexperience (58.0%), lack of information (51.9%), difficulty in addressing sexual orientation/behavior (46.3%) and fear of stigmatization (46.0%) were the main struggles pointed by the participants in providing SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people.

Over a third of the respondents (37.0%) considered that their level of preparedness to carry out a family planning consultation to LGBTQIA+ individuals was ‘poor’ or ‘none’, evoking the prevention of STDs (68.5%), the control of menstrual symptoms (58.3%) and the fertility preservation/reproductive planning (52.5%) as the main reasons that lead LGBTQIA+ patients to these appointments.

Concerning the use of contraception by LGBTQIA+ people, 24.2% of the participants believed that they often use contraceptive methods and 23.6% considered that they use less effective contraceptives. Moreover, 5.6% and 23.8% of the physicians considered that the rate of unwanted pregnancies and the existence of multiple partners were higher in the LGBTQIA+ community, respectively.

Fear of stigmatization (81.5%), healthcare providers without training (66.7%) and previous negative experiences (55.9%) were some of the barriers referred by participants that could hinder the access of LGBTQIA+ individuals to SRH assistance. In addition, near half of the physicians (50.6%) considered that it would be beneficial to have an SRH consultation specifically for LGBTQIA+ people (Table II).

Training needs on SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people

Most of the respondents (96.0%) recognized the importance of holding trainings/workshops dedicated to SRH care to the LGBTQIA+ community (Table II).

Factors influencing physician’s knowledge and practices

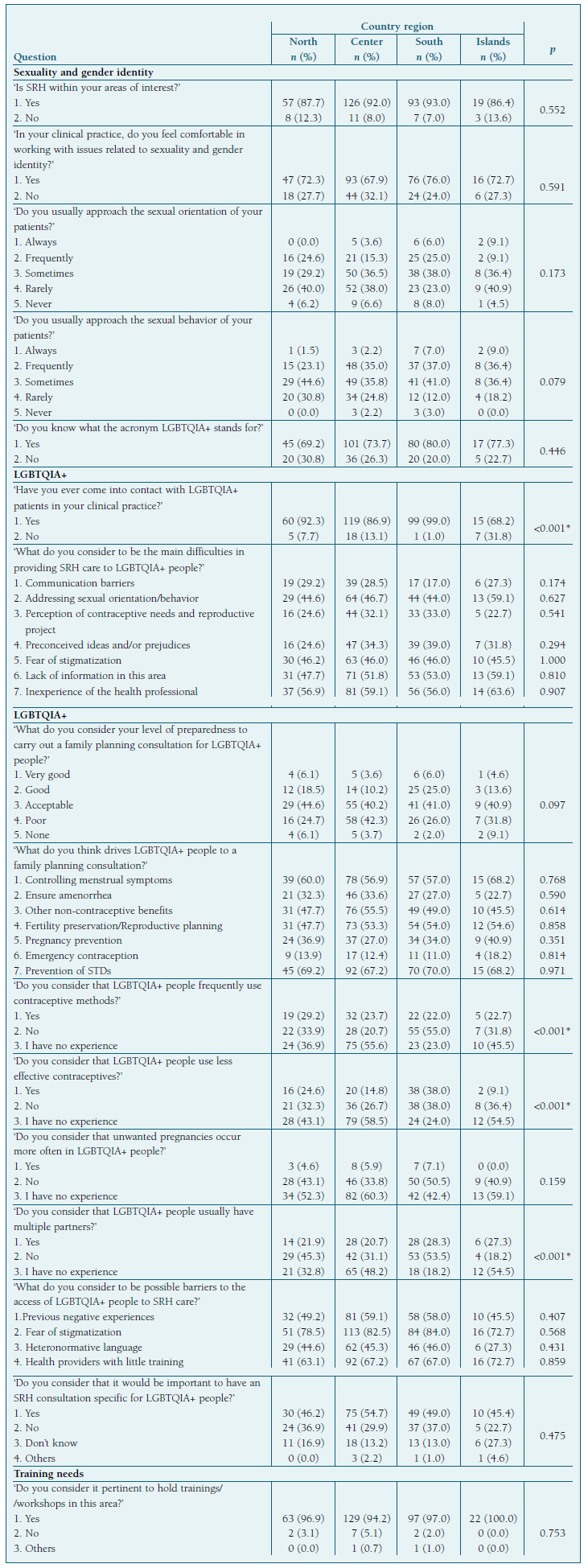

Comparative analysis revealed that physician age, specialty, professional category/years of clinical practice and region of the country where they work from significantly influenced their knowledge and practices.

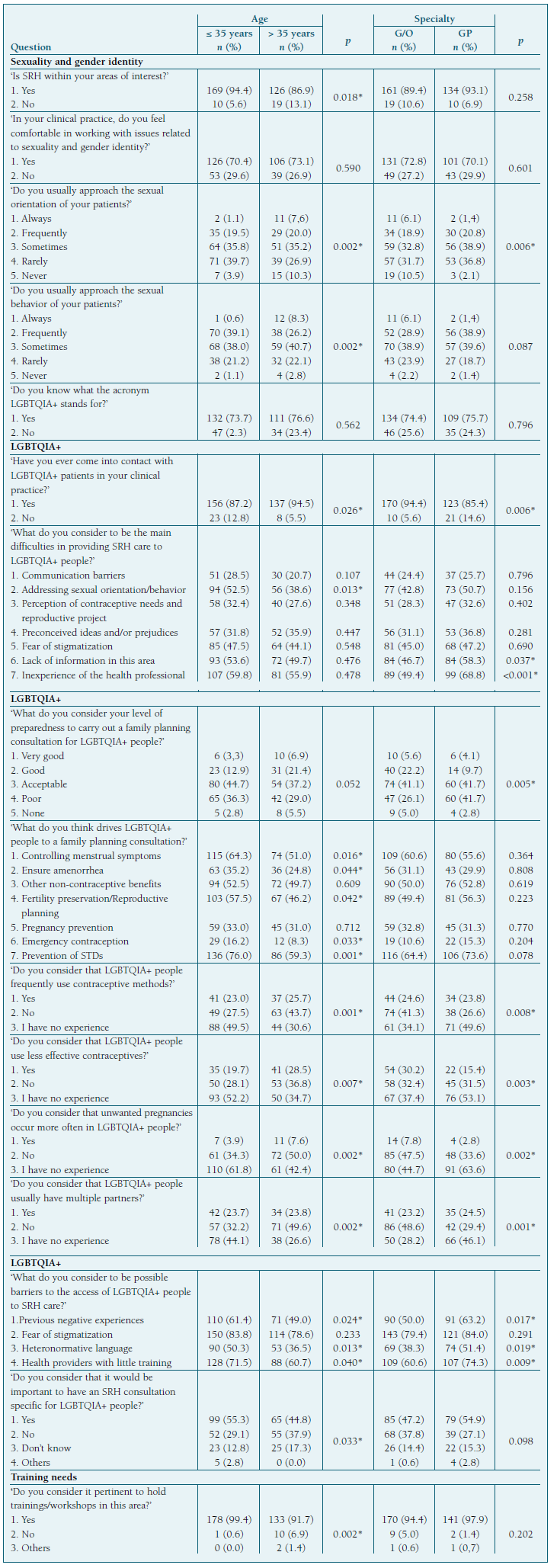

Physicians less than 35 years of age showed less experience and knowledge considering SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people than older professionals, recognizing more often the pertinence of holding trainings/workshops in this field (Table III).

Table III Physician experience, level of knowledge and training needs on SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people per age and specialty.

Likewise, physicians of GP self-assessed more frequently clinical inexperience and lack of information on SRH counseling to LGBTQIA+ individuals when compared to G/O practitioners (Table III).

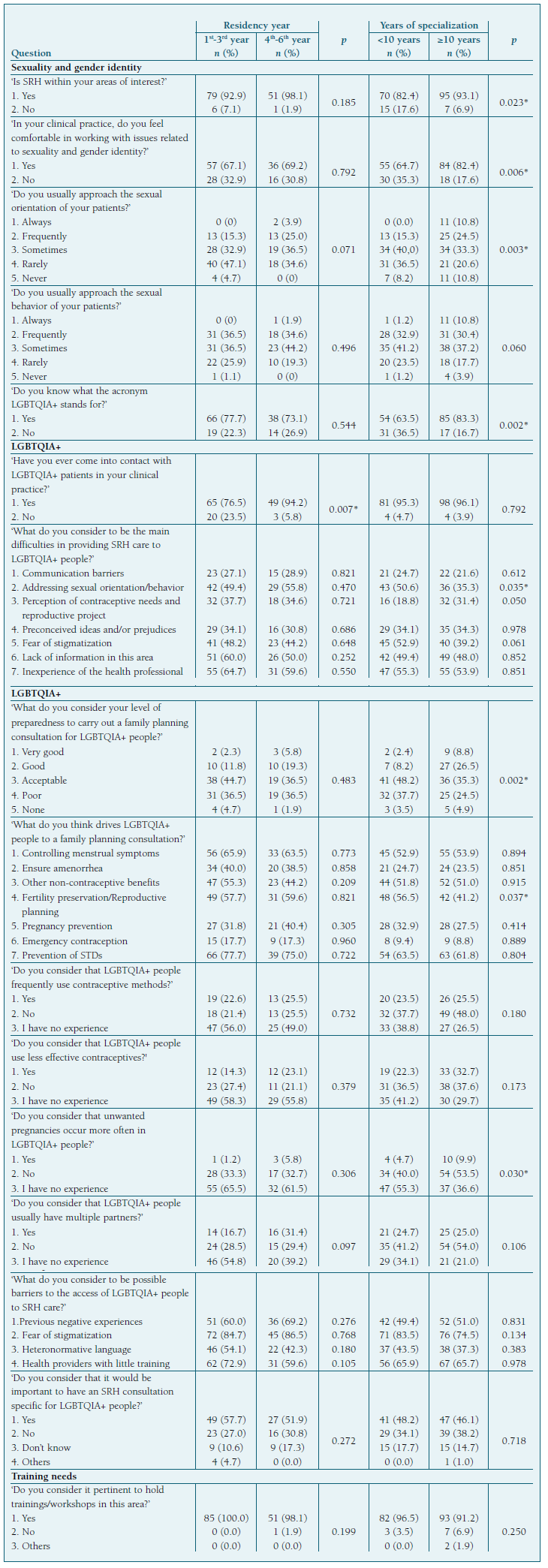

Overall, residents from the 4th-6th years and specialists with more than 10 years of specialization revealed to be more instructed and prepared to deal with issues related to sexuality and gender identity and providing SRH care to LGBTQIA+ individuals than physicians that accounted fewer years of clinical practice (Table IV).

Professionals that worked in the North and South regions of the country had a higher clinical involvement with sexual and gender minorities, while those from the Centre region and Islands described less experience in this field (Table V).

Table IV Physician experience, level of knowledge and training needs on SRH care to LGBTQIA+ people per professional category and years of clinical practice (residents and specialists).

Discussion

As to our knowledge, this is the first nationwide survey assessing the perspective of G/O and GP physicians on SRH providing care to LGBTQIA+ people with the focus on their clinical experience, level of knowledge and training needs.

In our study, even though the majority of the participants (91.1%) considered SRH one of their areas of interest, 25.0% of them were unaware of the meaning of the LGBTQIA+ acronym. Similarly, although most physicians (71.6%) felt comfortable in approaching issues related to sexuality and gender identity, more than 40.0% affirmed that they ‘have no experience’ when questioned about contraceptive practices and occurrence of unwanted pregnancies in the LGBTQIA+ community. Additionally, 40.8% and 23.5% of the physicians ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ used to address the sexual orientation and the sexual behavior of their patients, respectively. These results demonstrate that, in general, LGBTQIA+ SRH has not been carefully assessed and guided in clinical practice, which is in accordance with the study “Health in Equality” of ILGA Portugal, in which most of the surveyed LGBTQIA+ individuals (83.0%) reported that their sexual orientation had never been directly questioned in the context of a medical consultation and that 70.0% of health professionals assume that the patient is heterosexual or has sexual behavior exclusively with people of the opposite sex4.

Overall, most of the respondents (90.4%) had already contacted with LGBTQIA+ patients in their clinical practice, although only 21.6% self-assessed a ‘very good’ or ‘good’ preparedness to providing them with SRH care. Moreover, the main difficulties reported by physicians in this assignment were their own inexperience (58.0%) and the lack of information (51.9%) within this domain.

As conveyed by the literature, contraceptive counselling and SRH care are of unquestionable importance for all population, including LGBTQIA+ individuals, not only within the scope of STDs diagnosis and prevention, but also regarding the definition of a reproductive project, contraception-related issues and prevention of unwanted pregnancies.3,5-7,10-12 Nonetheless, in our study, the prevention of an unwanted pregnancy (32.1%) and the access to emergency contraception (12.7%) were the least mentioned reasons that drive LGBTQIA+ people to a family planning consultation.

According to the published evidence, LGBTQIA+ women are more likely to use less effective contraceptive methods or none at all compared to heterosexual women, thus being exposed to an increased rate of unintended pregnancy and STDs.3,5-7,10-12 In our study, 34.8% of the respondents also considered that LGBTQIA+ individuals don’t use frequent contraception. However, the majority considered that LGBTQIA+ people don’t use less effective contraceptives (32.0%) neither have an increased rate of unwanted pregnancy (41.3%) or multiple partners (40.0%), demonstrating a huge lack of knowledge and inexperience on these SRH related-issues.

With respect to the main barriers in the access of the LGBTQIA+ community to SRH care, the majority of the inquired physicians reported the fear of stigmatization (81.5%), the providers’ insufficient training (66.7%) and the existence of previous negative experiences (55.9%) as the most significant reasons.

Similarly, in the study “Health in Equality” of ILGA Portugal, 17.0% of the surveyed LGBTQIA+ individuals had already been subject to discrimination or inappropriate approaches in health services, 66.0% feared that mentioning their sexual orientation or gender identity would provoke discriminatory reactions during medical consultations and 37.0% had already omitted their sexual orientation and/or sexual behavior in a situation where it would have been important to mention this information4. Also in the European LGBTI 2020 Survey, 8.0% of the Portuguese transgender people and 6.0% of intersex individuals faced difficulties in accessing healthcare due to their gender identity and/or expression, 19.0% of trans people had been or had considered going abroad to access specific medical interventions/medications and 9.0% of intersex people reported not having access to adequate health assistance9.

Despite not consensual, half of the physicians considered a family planning consultation specifically for LGBTQIA+ individuals as a relevant accomplishment. On the contrary, other respondents highlighted the importance of training and developing competencies in this field instead of creating a consultation addressed to LGBTQIA+ people that may even enhance stigmatization. Likewise, when directly surveyed, the majority (96.0%) of the physicians recognized the pertinence of holding trainings/workshops in this area.

In addition, our findings revealed that physician’s individual factors such as age, medical specialty, professional category/years of clinical practice and region of the country where they work from, significantly impact their experience, level of knowledge and training needs on SRH care to the LGBTQIA+ community. Therefore, although both specialties were directly involved with SRH care in their clinical practice, GP professionals demonstrated less knowledge and clinical experience compared to G/O practitioners, reinforcing the need of additional training in this domain. Moreover, younger physicians and those with fewer years of clinical practice also showed to be less prepared to deal with sexuality and gender identity issues and providing SRH assistance to LGBTQIA+ people. Furthermore, professionals that worked in the North and South regions, which correspond to the most urbanized and inhabited parts of the country, revealed a higher involvement with sexual and gender minorities, contrarily to those from the Centre region and Islands.

A major strength of the present study is that it is a nationwide survey that included a significant number of G/O and GP physicians directly involved with SRH care in Portugal. Moreover, our findings may have important implications on clinical practice and healthcare assistance to sexual and gender minorities, highlighting the biggest challenges faced by physicians and their significant training needs on this subject, thus representing an important contribution to the literature.

The conclusions from this study should be evaluated within the context of its potential limitations. First, its self-assessment design, considering the opinion and perspective of health professionals involved with SRH, might have introduced inherent bias of information as their answers will be notably more subjective and dependent on their clinical experience. Besides, the use of an online and voluntary questionnaire, originally designed for this purpose, could be associated with several constraints, namely regarding its validation, disclosure and physicians’ adherence. In this way, it would be pertinent to extend this survey to a larger number of participants, increasing its duration and using other means for the questionnaire’s advertisement.

Conclusions

Physicians (G/O and GP) had insufficient knowledge and clinical experience regarding SRH care in sexual and gender minorities, recognizing their limitations and the imperious need of training in this field. These findings were more evident among General Practitioners, in young physicians and in those with less years of clinical practice, particularly if they work in the Centre region or Islands. Therefore, future training sessions aimed at physicians dedicated to SRH are fundamental in order to develop their skills and competency in providing care to the LGBTQIA+ community and improve global health assistance in our country.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions

DA, AR and DM contributed to the concept, study design, analysis and interpretation of data. DA and AR were responsible for the article draft. TB supervised the team research and revised the article critically. All authors approved the final article as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.