Introduction

Primary aldosteronism (PA), also known as Conn’s syndrome, was first reported by Conn et al., and is described as a clinical syndrome characterized by hypertension, hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis, as a result of autonomous aldosterone production1-3. PA is commonly caused by an adrenal adenoma or by adrenal hyperplasia (unilateral or bilateral) 4. With a prevalence between 3 and 10% in the hypertensive population5,6, PA is one of the leading causes of secondary hypertension.

Hypertension affects 2-8% of pregnancies, and is associated with significant maternal-fetal morbidity7. Nevertheless, PA is a rare diagnosis in pregnant women1,2,8, with an estimated incidence of 0,6-0,8% and is scarcely reported in postpartum9. However, that is likely significantly underestimated due to difficulty of establishing a diagnosis1. Diagnosing PA during pregnancy or the postpartum period is challenging due to heterogeneity in clinical manifestations and to marked alterations in the renin angiotensin system in normal pregnancy8. Moreover, it remains uncertain which patients should be screened for PA in the postpartum period10.

Herein, we report a case of a pregnant woman with primary aldosteronism, diagnosed during the postpartum period.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Case Report

A healthy 31-year-old Caucasian GII/PI woman at 35 weeks of gestation was referred to our emergency department due to new onset of hypertension and mild headaches. The previous gestation, which occurred nine years earlier, was uneventful, with a normal tensional profile, with a vaginal term birth.

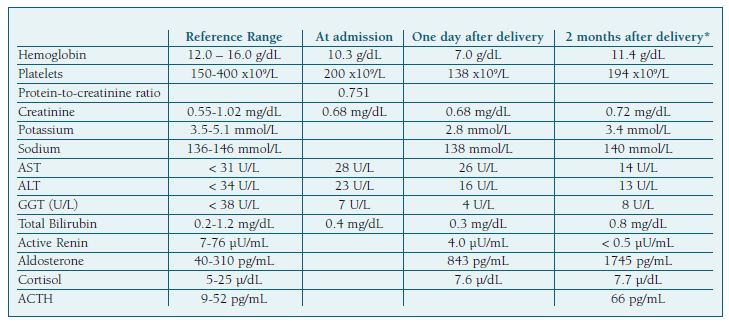

The initial evaluation reported high blood pressure (182/106 mmHg) and proteinuria, determined by the urine dipstick test 2+. Severe hypertension was documented following blood pressure re-evaluation. Laboratory tests (Table I) were normal with the exception of a protein-to-creatinine ratio in a random urine specimen of 0.751 mg/mg. Intravenous labetalol was introduced aiming to control blood pressure (duration of 6 hours, cumulative dose of 300 mg at a maximum infusion of 80 mg/h), according to local protocol. Preeclampsia with severity criteria was assumed due to uncontrolled severe blood pressure and labor was induced at 35 weeks of pregnancy, resulting in a vaginal delivery of a baby with 2645 g. (Figure 1).

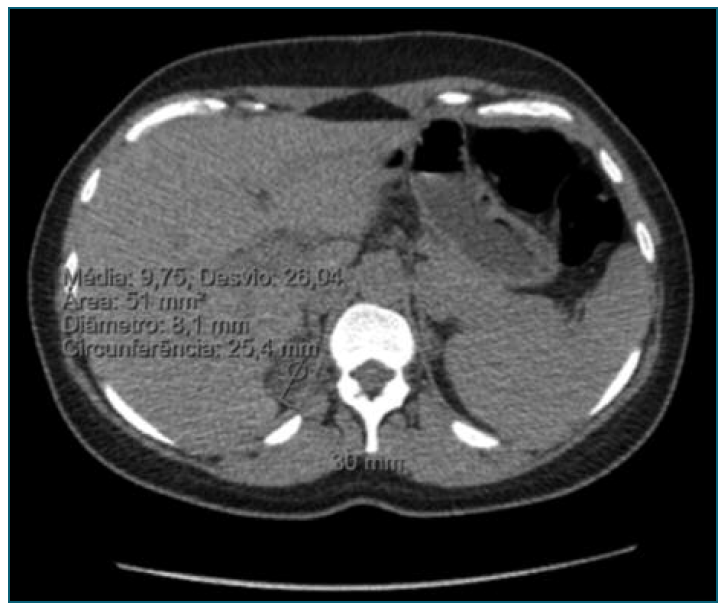

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography showing a hypodense solid adrenal mass in the right adrenal gland.

After delivery, despite antihypertensive treatment with intravenous labetalol (max 80 mL/h) and oral perindopril (5 mg per day), the patient blood pressure remained elevated (160/100 mmHg). Subsequent laboratory evaluation included the concentration of potassium (which remained low at 2.7-2.9 mmol/L despite intravenous supplementation), plasma aldosterone (843.0 pg/mL) and active renin (4.0 µU/mL) (Table I). According to these data, PA was diagnosed and the treatment readjusted. In order to control blood pressure, an extensive regimen was prescribed (perindopril 5 mg bid, spironolactone 50 mg id and nifedipine 60 mg id). The patient was discharged eight days after delivery with strict blood pressure control and with scheduled etiologic evaluation.

An abdominal CT scan three months after delivery revealed a 30 mm hypodense (9 HU) solid adrenal mass, which was consistent with adrenal adenoma. A right laparoscopic adrenalectomy was proposed and performed 13 months after birth. Following surgery, the patient discontinued all anti-hypertensive medications, achieving good blood pressure control and serum potassium returned to normal values. Pathologic evaluation of the adrenal gland revealed an aldosterone-secreting adrenal adenoma, which confirmed the medical imaging suspicion.

Discussion

Hypertension is a common clinical complication of pregnancy, and preeclampsia complicates around 2-8% of pregnancies7. Secondary causes of hypertension affect 0.24% of pregnancies and pose a significant short and long-term risk of complications for both mother and babies5. In this patient, resistant hypertension and hypokalemia during postpartum raised concern for a primary aldosteronism.

PA is a cause of secondary hypertension and one of the most potentially treatable5. This is relevant because PA is associated with adverse maternal-fetal outcomes such as severe hypertension, superimposed preeclampsia, placental abruption, and preterm delivery2,5. In fact, the estimated risk of developing preeclampsia associated with primary aldosteronism in pregnancy can be up to 31%2,11, which is higher than in women with primary chronic hypertension6.

As shown in this case, several factors contribute to the difficulty of diagnosing PA in pregnancy.

First new onset of severe hypertension in late pregnancy in a previous normotensive woman is generally interpreted as a hallmark of preeclampsia, potentially neglecting other causes of hypertension9. Secondly, distinguishing PA from preeclampsia is further complicated by the fact that proteinuria may be present in PA12. Because of this, it is hard to understand whether there was a superimposed preeclampsia11. Thirdly, the clinical manifestations of PA are heterogeneous, ranging from severe complications (hypertension, preterm delivery or even fetal loss) to little impact on pregnancies5,11.

Additionally, during pregnancy there are profound alterations in the renin-angiotensin system4,6,13 including: 1) elevated renin concentrations due to extra-renal release from ovaries through estrogen stimulation and maternal decidua8,9 and 2) increased liver production of angiotensinogen, which elevates aldosterone and angiotensin II levels8,14. There is also an increased aldosterone secretion because progesterone is a competitive inhibitor of aldosterone in the distal convoluted tubule8-10. The balance between progesterone and aldosterone leads to normal blood pressure in healthy pregnant women8. At the end of pregnancy, the reduction of circulating progesterone levels releases the action of aldosterone, triggering the peri-partum and postpartum presentation of hypertension in PA6,10. This may explain why some cases of PA can have normal or mildly elevated blood pressures during pregnancy, but presented with severe postpartum hypertension.

Currently, the diagnostic criteria for PA in pregnancy is not well defined2. Nonetheless, the most recent guidelines from the Endocrine Society for the diagnosis of PA recommend using the plasma aldosterone/renin ratio (ARR) to detect possible cases4. Confirmatory tests are not necessary in pregnant women with spontaneous hypokalemia, high aldosterone levels of more than 20 ng/dL (550 pmol/L) and a suppressed renin4,8.

Some authors suggest that PA should be screened in select patients, especially those with severe resistant hypertension and/or spontaneous hypokalemia4,8, or patients with hypertension at a young age12.

An adrenal CT scan is suggested as the first study to determine the subtype of PA4. If a solitary, hypodense, unilateral macroadenoma is found and there is normal contralateral adrenal morphology, an adrenal adenoma is the most probable diagnosis4,5. Since during pregnancy CT scan is contraindicated, adrenal MRI could be the baseline exam8,9.

When feasible, laparoscopic adrenalectomy is the treatment of choice, ideally performed in the second trimester5,13. Following a conservative management during pregnancy can be challenging because spironolactone and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are contraindicated8,15. After gestation, both spironolactone and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are considered safe for breastfeeding12.

This case illustrates the difficulty of diagnosing primary aldosteronism in both pregnancy and the post-partum period, primary aldosteronism in pregnancy and the postpartum period, and the overlap of clinical manifestations between PA and preeclampsia. It also highlighted the importance of investigating secondary causes of hypertension, such as PA in women with severe and resistant hypertensive disorder. Hypertension and hypokalemia are unreliable markers of PA, and despite hypokalemia not being a sensitive tool for screening, potassium levels should be checked in all resistant hypertension.

Prompt diagnosis followed by surgical treatment led to the resolution of hypertension and hypokalemia, reducing the risk of downstream cardiovascular events.

Author contribution statement

Daniela Agostinho David: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Visualization; Writing - review & editing. Rafaela Pires: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Visualization; Writing - review & editing. Ana Filipa Marques: Supervision; Visualization; Writing - review & editing. Isabel Santos Silva: Supervision; Visualization; Writing - review & editing.