Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease defined by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity1. Endometriosis usually affects women in reproductive age. Its incidence is difficult to determine, but it can be estimated at 10%2,3,4.

Pelvic endometriosis is the most common site for the development of the disease. However, approximately 12% of all cases of endometriosis can occur in extrapelvic locations1,2. The most common site of endometriosis implantation outside the pelvis is in the thoracic cavity, which can involve the parenchyma, pleural surfaces, and diaphragm. Diaphragmatic endometriosis (DE) is a rare disease, with a prevalence ranging from 0.1% to 1.5%2. Most of DE patients are asymptomatic (70%)5, however they may present with non-specific symptoms such as chronic shoulder or pleuritic chest pain, right upper quadrant pain, and cough1. These symptoms may or may not be related to menstruation1.

DE is often a misdiagnosed condition2. It frequently occurs in association with pelvic endometriosis (50% to 90%), for this reason, a systematic inspection of the diaphragm during laparoscopy for pelvic endometriosis is recommended2,5.

Currently, the treatment of DE is based on a small case series from the literature and a few case reports. We present two cases of diagnosis and laparoscopic treatment of DE associated with pelvic endometriosis.

Case 1

A 44-year-old nulliparous woman was referred to the pelvic pathology appointment at our institution. She suffered recurrent pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea, with a visual analog scale of 8 in 10 during the menstrual cycle. The patient mentioned a history of right catamenial shoulder pain (7/10) and right upper abdominal pain (7/10) with six months of duration. She denied dyschezia and a history of trauma or chronic lung disease. The patient had smoking habits. She had a history of a previous laparoscopic resection of pelvic endometriosis, with a colorectal segmental recession, and partial cystectomy five years ago. The symptoms were refractory to medical treatment (combined oral contraceptives (COC) and GnRH agonists). Pelvic ultrasound showed adenomyosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed deep pelvic endometriosis with involvement of the rectovaginal pouch, uterosacral ligaments, and adjacent paraovarian adhesions. MRI also showed a 6 cm hyperintense nodule at the level of the right diaphragm, suggesting endometriosis (Figure 1).

Case 2

A 32-year-old nulliparous woman with a history of dysmenorrhea (9/10), as well as dyspareunia (9/10) and catamenial shoulder pain (8/10), was referred to our institution. The patient had no known history of pneumothorax or catamenial hemothorax. She had no known medical comorbidities and no history of previous surgery. MRI demonstrated deep pelvic endometriosis with involvement of the ovaries, rectovaginal pouch, and uterosacral ligaments. MRI also revealed a 5 cm nodular density along the right hemidiaphragm, suggesting endometriosis. The medical treatment was primarily hormonal-based therapies encompassing COC and GnRH agonists. The simptoms persisting despite hormonal treatment.

Procedure

In both cases, the procedure was performed laparoscopically under general anesthesia with a double-lumen endotracheal tube for controlled ventilation due to the risk of pneumothorax. The patient was lying in dorsal lithotomy position and Trendelenburg position. A 10 mm optical trocar with a zero-degree endoscope (umbilical port) was used. Under visualization, three additional 5 mm auxiliary trocars, one placed in the suprapubic area and two positioned laterally, were placed to gain access to the pelvic cavity.

A complete evaluation of the peritoneal cavity was performed. Operative findings included a severe pelvic disease involving the ovaries, and the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac. In both cases, exploration of the upper abdominal cavity confirmed infiltrative endometriosis of the anterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm.

After laparoscopic excision of pelvic endometriosis, the Trendelenburg position was reversed and the patient was placed in left lateral decubitus position for an adequate exposure of the right side of the diaphragm. Assessment of the right anterior hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left side of the diaphragm was carried out using the umbilical port.

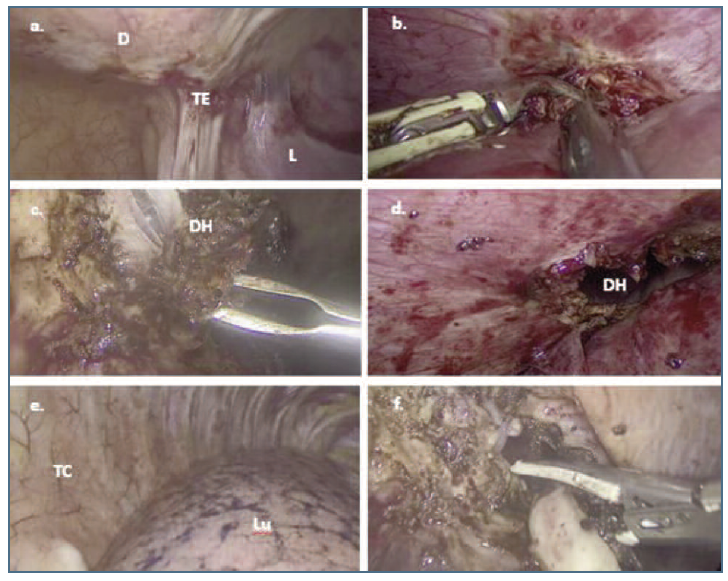

After clear identification of lesion edges, the lesion was meticulously dissected from medial to lateral using bipolar energy. Grasping forceps and monopolar energy were used for traction and extraction of the lesion. Most of the lesion was removed before opening the diaphragm and creating an iatrogenic pneumothorax. Laparoscopic full-thickness resection of the diaphragm was performed using Ligasure© assisted by grasping forceps. An accurate exploration of the thoracic cavity with the endoscope through the diaphragmatic defect did not demonstrate any disease involving the lung parenchyma and pleural surfaces. The surface of the lung showed findings consistent with patient 1 smoking habits (Figure 2).

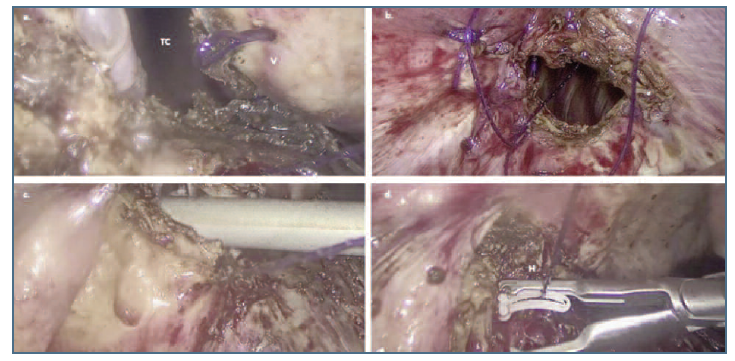

The defect on the right hemidiaphragm was repaired with a barbed suture, in double layer and running suture. Before the final closure knot, a laparoscopic aspirator was introduced into the thoracic cavity, and a gentle CO2 suction was performed, avoiding the use of a chest drain. An hemolock clip was inserted (Figure 3).

Figure 2 a. Laparoscopic view of endometriosis lesion in the inferior surface of right hemidiaphragm. b. Laparoscopic section of adherence between liver and inferior surface of right hemidiaphragm. c. and d. Laparoscopic view of the diaphragmatic nodule in the course of partial diaphragmatic resection with opening of the thoracic cavity. e. Laparoscopic view of the right thoracic cavity after introducing the optic through the diaphragmatic defect. f. Laparoscopic full-thickness resection of deep endometriotic nodule at right hemidiaphragm. D: right hemidiaphragm; TE: transmural endometriosis; L: liver; DH: diaphragm hole; TC: thoracic cavity; Lu: lung.

Figure 3 a and b. Laparoscopic suture of the defect in the right diaphragmatic using barbed suture. c. Introduction of the aspirator through the diaphragmatic defect before final closure stitch. d. Closure with hemolock clip. TC: thoracic cavity; V: barbed suture; H: hemolock clip.

The procedures were successfully performed. The estimated total intra-operative blood loss was less than 250 ml. There were no intra- or post-operative complications in either procedure. After surgery, both patients remained stable, without episodes of pain, and left the hospital 2 days after the operation. There were no recurrent symptoms at 6 months of follow-up. Histological evaluation of the surgical specimen confirmed endometrioc lesions.

Discussion

Endometriosis usually occurs in the female pelvis, but occasionally can occur in extrapelvic locations (12%)6. Endometriotic involvement of the diaphragm is rare, with a prevalence ranging from 0.1% to 1.5%1,9. DE is silent in 70% of the cases3 but when symptomatic can be clinically significant1,2,7. It can arise independently or in association with thoracic endometriosis1.

The right side of the diaphragm is more frequently affected, occurring in 95% of cases1,8. The theory of retrograde menstruation, described by Sampson, defends that menstrual reflux finds a barrier in the falciform ligament8, preventing endometrial cells from reaching the left hemidiaphragm.

We report two cases of women in reproductive age with DE. Both had shoulder and right upper quadrant pain, apparently in consequence of endometriotic lesions.

In these cases, women were symptomatic. However, most cases of DE are asymptomatic. In fact, some authors report that up to 70% of the patients will be asymptomatic5. Clinical symptoms are variable and non-specific, or similar to other disorders1. The severity of the symptoms varies with the depth of dia-phragm involvement8. For this reason, the diagnosis can be challenging and can be suspected in the presence of a history of pelvic endometriosis and recurrent catamenial upper abdominal pain6.

Preoperative image studies should be used to map suspicious lesions and plan the surgery9. MRI is preferable to identify and define the extension of endometriosis1 with a sensitivity of 78-83%5,10. MRI imaging depends on the phase of the menstrual cycle9. However, for a definitive diagnosis, surgical exploration and biopsy are required3,11. In our cases, MRI showed an endometrial lesion on the right side of the diaphragm and no lesion of pulmonary endometriosis.

Medical or surgical treatment can be performed. The choice must take into account the patient’s medical history and the severity of the symptoms8. In symptomatic cases, medical treatment is the first line, reserving surgery for women who have refractory symptoms related to hormonal suppression2,11. In our cases, medical treatment failed, so a laparoscopic full-thickness resection was performed.

There are different types of DE lesions, classified according to the extension and infiltration of the disease2. Different diaphragmatic surgical techniques have been described based on the type of lesions. Surgical treatment of diaphragmatic lesions included plasma ablation, hydro-dissection plus resection, laser CO2 vaporization, and bipolar cauterization; with the aim of vaporizing small superficial lesions while preserving the integrity of the diaphragm2. In the case of transmural infiltration of the diaphragm, a full-thickness resection followed by primary repair of the defect is indicated5. In our cases of full-thickness involvement of the diaphragm, before performing the final knot we use a laparoscopic aspirator for inflation of CO2 into the chest cavity and avoid the use of a chest drain. This last step reduced surgical time, the risk of complications, and increased patient comfort.

The laparoscopic technique is an excellent method for evaluating and treating DE9. When the disease is extensive and larger diaphragmatic resections are required near the central tendon, thoracoscopic surgery can be a useful tool, allowing the identification of phrenic nerve paths, and reducing the risk of incomplete resections, recurrences and postoperative complications1,7,9. Likewise, when the thoracic cavity is involved, thoracic and abdominal approaches should be performed, applying a combined procedure of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery/laparoscopy1,9.

The concomitant occurrence of diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis is observed between 50% and 90%2. Exploration of the diaphragm during a minimally invasive surgical approach should be done routinely, and surgical treatment should be included to prevent the possible progression of the lesion5,8.

Minimally invasive treatment of DE has a satisfactory outcome, with symptom control in around 85-100% of patients and a low risk of perioperative complications (<2%)2.

Conclusion

DE is a rare condition. Diagnosing DE is challenging due to variations and unspecified symptoms and requires high level of clinical suspicion. Medical treatment for DE is an option, however patients will frequently need a surgical approach. As the authors report, the minimally invasive approach confirms the diagnosis and relieves the symptoms. This disease can be safely treated by laparoscopy without major intra/post-operative complications. Multidisciplinary management and the surgeon’s experience are fundamental for an adequate minimally invasive treatment of this condition.

Frequently, involvement of the diaphragm is concomitant with pelvic endometriosis. Therefore, when a patient undergoes pelvic surgery for endometriosis, exploration of the lower diaphragm should be routinely assessed.

With improved diagnostic criteria and greater clinical suspicion, the prevalence of the disease will increase. With this report, we aim to describe our experience and contribute to a better understanding and management of the disease.