Introduction

Fetal pleural effusion (FPE) refers to the accumulation of fluid in the pleural space and is classified as a benign finding in approximately 50% of cases. The reported prevalence ranges from <1 to 2.2% among neonates admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit1. Neonatal death associated with FPE usually results from non-immune fetal hydrops, preterm birth, and pulmonary hypoplasia. It is known that fetal pleural effusions are associated with significant neonatal morbidity and mortality, and when diagnosed, referral to a specialized perinatal center for detailed ultrasound evaluation to search for structural abnormalities or findings suggestive of congenital infections or fetal anemia is essential2.

The placement of an intrauterine shunt is recommended in cases of extensive pleural effusions with significant mediastinal deviation or hydrops, as several studies have shown better outcomes in perinatal survival, particularly in hydropic fetuses3.

Clinical Case

A 36-year-old pregnant woman, G3P1 (1 cesarean section and 1 spontaneous abortion), with no relevant personal medical history was being followed-up in a hospital consultation.

Combined screening for first-trimester aneuploidies as well as pre-eclampsia screening were low-risk. The remaining first-trimester routines were normal.

At the second-trimester ultrasound, performed at 21 weeks and 5 days, a unilateral right-sided pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and slow gastric filling were identified. The patient was referred to a fetal medicine consultation, where a multidisciplinary team recommended amniocentesis, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) array, and a follow-up ultrasound at 24 weeks. Viral serologies were requested, and a genetic specialty opinion was also required.

The CGH Array showed deletion of the X Chromosome associated with ichthyosis (family history of male parent). Viral serologies were all negative, including Parvovirus and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) in amniotic fluid. In the reevaluation ultrasound at 22 weeks and 1 day, the pleural effusion had smaller dimensions (7 × 4 mm), and considering the favorable evolution and absence of changes in invasive tests, the couple chose to continue the pregnancy. Fetal echocardiogram revealed no abnormalities. Later, in the ultrasounds at 23 weeks and 5 days; 25 weeks and 6 days; 28 weeks and 1 day, growth and flow measurements were normal, and the effusion significantly reduced in size, measuring 7.8 × 3.9 mm at the 28-week and 1-day evaluation.

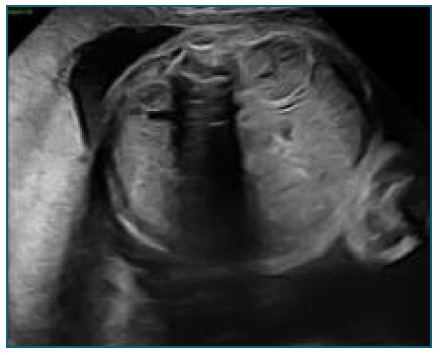

At 32 weeks (Figure 1), the fetus was found to have imaging findings consistent with fetal hydrops (bilateral pleural effusion and ascites), showing a sudden deterioration compared to the ultrasound performed at 28 weeks. Flowmetry was normal, but considering the worsening, a multidisciplinary meeting opted for hospitalization with induction of lung maturation and placement of pleuro-amniotic shunt.

The shunt placement, at 32 weeks and 3 days (Figure 2), occurred without complications, although laborious due to fetal positioning, pleural fluid was collected for analysis. The shunt appeared to be functioning with clear improvement in effusion (Figure 3).

However, 12 hours after shunt placement, ultrasound showed a large right pleural effusion - Figure 4 (larger than before shunt placement - Figure 5). The ultrasound image suggested migration of the catheter into the thoracic cavity with atelectasis and reappearence of pleural effusion (Figure 6).

Considering the findings, the decision was made to terminate the pregnancy due to worsening pleural effusion, with thoracic drainage performed to facilitate ventilation in the postnatal period, prior to cesarean section.

Approximately 50 cc of yellow citrine fluid was drained and sent for study. Cesarean section was performed at 32 weeks and 3 days without complications, and the newborn had an APGAR score of 7/9/9, wei-ghing 2090 g, admitted to the Neonatal intensive-care unit (NICU).

There was worsening of respiratory difficulty under non-invasive ventilation in the first hours of life, and a chest X-ray (Figure 7) revealed a large right pleural effusion. In this context, invasive ventilation and thoracentesis (pleural fluid with characteristics of chylothorax, negative bacteriological examination) were performed, followed by placement of a chest tube. Approximately 40 mL/day was drained with progressive reduction. Accidental removal of the chest tube occurred on day 4, with radiological surveillance showing complete resolution of the effusion by day 13. Room air was achieved by day 5 of life. The newborn was discharged from the hospital at 38 days of life, exclusively breastfed, with no recurrence of pleural effusion. Reevaluation at 2 months in clinic (corrected age of 2 weeks) showed good growth and psychomotor development. Currently, the newborn only requires follow-up in neonatology and pediatric surgery with indication for surgical removal of the Intrapleural shunt at 6 months.

Discussion

There are several complications associated with pleural effusion, with polyhydramnios and pulmonary hypoplasia being the most frequent. Polyhydramnios usually results from difficulty swallowing or underlying cardiac insufficiency secondary to vessel compression due to mediastinal deviation2.

Pulmonary hypoplasia occurs essentially due to extrinsic compression of the lung parenchyma, preventing its normal development. Shunt placement not only contributes to identifying the causal factor but also helps prevent fetal pulmonary hypoplasia phenomena5.

In fetuses with substantial pleural effusions, such as hydrothorax or chylothorax, the placement of a pleuroamniotic shunt can relieve elevated intrathoracic pressure, thereby reducing the risk of developing pulmonary hypoplasia4-6.

This approach is supported by systematic reviews, which found that the survival rate for fetuses with pleural effusion and hydrops who underwent shunting was significantly higher than for those managed expectantly (over 60% versus less than 25%, respectively). However, only uncontrolled observational data from case reports and small case series were available for review, as no controlled trials have been conducted7-9.

The most commonly reported complications are rupture of membranes leading to preterm delivery, although other potentially significant ones such as malfunctioning and migration of the shunt are frequently quoted10. A rare complication, as described in this case, is dislodgement of the shunt into the fetal chest.

There are few cases described in the literature regarding possible complications associated with fetal pulmonary shunt placement. One series published in 2005 by Sepulveda and his group, refers precisely to the long-term follow-up of 3 cases dislodgement of pleuro-amniotic shunt, all three infants were discharged without any attempts of removing the shunt and remained asymptomatic until the publication of the article (two of them with 2 years old and one with 10 months-old) (11.

Ultimately, the complication of a pleuro-amniotic shunt dislodging within the thoracic cavity can be identified prenatally via ultrasound. While preventing this issue may be difficult, if detected, a conservative approach to management appears to be a viable option11.

Finally, this case, due to its rarity and complexity, highlights a delicate clinical scenario and alerts to a possible complication underlying the placement of this device.