Introduction

Cysts arising from the uterus are a rare condition with few cases reported on the literature1. These rare tumors are known to have an estimated prevalence of 0.07%2. The most frequent subtype is the cystic adenomyoma, while others include cystic degeneration of fibromyomas, congenital Müllerian cysts, and other anomalies of Müllerian structures, such as a rudimentary uterine horn3.

Adenomyotic cysts are typically associated with adenomyosis. They correspond to ectopic endometrial glands and stroma and are generally small (2 to 5 mm), located at a minimum depth of 2.5 mm below the endometrial-myometrial junction, with surrounding hypertrophic and hyperplastic myometrium4),(5.

A distinct entity, referred to as uterine cystic endometriosis6, has been identified by a few authors. The literature on this subject is exceedingly limited. In this condition, a cyst originating from endometrial cells is described, characterized by the absence of contact with the myometrium. We subsequently present a case illustrating the occurrence of a cystic mass suggestive of uterine cystic endometriosis.

Clinical Case

A 49-year-old postmenopausal female, with a personal obstetric history of two vaginal births and a surgical history of right salpingectomy via laparoscopy, was referred to a tertiary hospital due to chronic pelvic pain persisting for several months. She reported no additional symptoms.

Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a normal-sized uterus with regular contours. The myometrium appeared irregular and heterogeneous without any discernible abnormal masses. The endometrium was regular and uniform, measuring 5.4 mm in thickness. A unilocular, anechoic formation measuring 6.7 × 6.1 cm was identified in the left iliac fossa, lacking abnormal vascularization. The origin of this lesion was unclear, though it was most likely a para-ovarian or peritoneal cyst.

Physical examination was unremarkable, except for an apparent enlarged uterus or mass detected during bimanual examination, which caused protrusion of the posterior vaginal wall. Serum CA-125 levels were wi-thin normal limits (16 U/mL). Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a normal-sized uterus and endometrium without detectable abnormalities. A round, right-sided mass measuring 68 × 62 mm was identified, displaying no septations or debris, consistent with the characteristics of an ovarian cystadenoma.

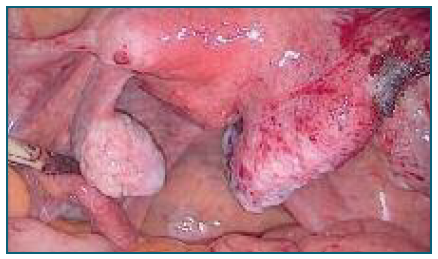

After counseling, the patient consented to a proposed laparoscopic bilateral adnexectomy. Diagnostic laparoscopy revealed a normal-sized uterus with both ovaries appearing normal. A mass approximately 7 cm in its largest dimension was observed arising from the serosal surface of the posterior uterine wall. It had a broad pedicle, regular wall, no vascularization, and appeared to contain fluid (Figure 1). The mass was in contact solely with the uterine serosa, without involvement of the myometrium. On the posterior uterine wall, near the origin of the uterosacral ligaments, small white vesicles measuring 0.5-1 cm were observed, suggestive of endometriosis lesions (Figure 2). Additionally, adhesions between the posterior uterine wall and the rectum were noted, causing obliteration of the posterior pelvic compartment.

The cyst was incised, draining clear serous fluid sent for cytological examination. The cyst capsule was excised using scissors and bipolar energy and submitted for pathological evaluation.

Cytological analysis of the fluid revealed blood cells, some macrophages, and epithelial cells without atypia, suggesting a benign cyst. Pathological evaluation of the cystic mass revealed it was primarily composed of columnar epithelium with underlying endometrial stroma positive for CD10, findings highly suggestive of an endometrioma. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and during follow-up consultations up to one year post-surgery, the patient reported significant improvement in pelvic pain.

Discussion

Regarding uterine masses, fibroids are the most common entity, considered the most frequent pelvic neoplasm, with a prevalence of up to 70-80%7-9. The primary differential diagnosis for fibroids is uterine sarcoma, a significantly rarer condition with an estimated prevalence of 1:10.000 to 1:50.0009. However, the differential diagnosis of uterine masses is broad, including adenomyomas (when adenomyosis cysts exceed 1 cm), variant leiomyomas, uterine carcinosarcoma, endometrial carcinoma, metastatic neoplasms (often originating from other primary neoplasms of the female genital tract), and hematometra8.

Uterine adenomyosis is a disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium, leading to hypertrophy of the surrounding myometrium. Some studies suggest that disruption of the junctional zone may result in ultrastructural changes and differential growth factor expression, facilitating the migration of endometrial cells into the myometrium10,11.

Diffuse adenomyosis results from the infiltration of endometrial tissue into the myometrium, causing hypertrophy of the adjacent myometrium and clusters of small cystic spaces filled with blood12 which rarely exceed 5 mm in diameter13. In rare instances, the lesion may present as a single cyst14 with a diameter ≥1 cm, filled with chocolate-brown fluid, referred to as cystic adenomyosis15.

Even rarer, with limited studies in the literature, are endometriomas of uterine origin, such as the one identified in this case6.

Based on the clinical findings, one might consider this lesion to be an adenomyoma. However, adenomyomas correspond to endometrial growth within the myometrium and are histologically accompanied by a surrounding muscular wall16, which was not observed in the pathological analysis of this specimen.

The presence of adhesions and white vesicles near the origin of the uterosacral ligaments suggests concurrent endometriosis, reinforcing the hypothesis that this mass could be an endometriotic cyst arising from the uterine wall, within the spectrum of uterine cystic endometriosis.

Accessory cavitated uterine malformation (ACUM) is a term introduced more recently to describe a non-communicating additional uterine cavity. Previously, ACUM has been referred to by various terms, such as juvenile cystic adenomyosis or “uterus-like mass.” Although ACUM should be considered in the differential diagnosis of the mass described in this case, it does not meet the diagnostic criteria established by leading authors. Specifically, the mass was not filled with chocolate-brown fluid, as described by Acién et al. (2010) (18. Furthermore, there was an absence of echogenic content in the anterolateral wall of the myometrium beneath the insertion of the round ligament, contrary to the criteria proposed by Acién et al. (2010) (18. Additionally, the patient was over 30 years old and did not present with a history of severe dysmenorrhea, as considered by Takeuchi et al. (2010) (20.

An extensive literature review identified only two other cases similar to ours, diagnosed as uterine cystic endometrioma21. Another author reported an endometriotic cyst in the retroperitoneum22. Therefore, it is pertinent to include this type of endometriotic cyst in the differential diagnosis of pelvic masses.

In conclusion, it is essential to consider the differential diagnosis of uterine cystic masses, as they are frequently mistaken for adnexal masses during preoperative evaluations. Endometriomas of uterine origin are rare and poorly defined in the literature; however, they should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pelvic cystic masses.