Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.1 Lisboa jan. 2016

Mobile identities: managing self and stigma in iPhone app use

Lorian Leong*

*London School of Economics, University of Western Ontario, 1151 Richmond St, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada. (l.leong@alumni.lse.ac.uk)

ABSTRACT

Based on qualitative analysis, this study empirically investigates the symbolic meanings in self-presentation, produced through the collection, placement, and use of mobile apps. Given the relatively unexplored nature of this subject matter, this study offers a range of views on the topic of mobile apps and the presentation of self among young adults in London in 2014. Findings showed that although impression management techniques on a smartphone screen were similar, the motivations differed. These motivations for impression management were primarily focused on the areas of social stigma, with specific reference to sexuality, race, and gender. Expansion of this research area can further investigate other motivations and applicability of this study to other social cultures and contexts.

Keywords: mobile; media; identity; presentation of self; apps; UX.

Introduction

In 2009, Apple noted that whatever the need, “there’s an app for that.”i Since then, smartphones and apps have become a burgeoning, personalised presence in the lives of people in both developed and emerging markets. As costs of mobile data and smartphones decrease, the use of mobile phone apps will increasingly integrate into our everyday habits. Mature smartphone markets already show the importance of smartphone and apps. Of the 128 minutes average UK users spend on their smartphones each day, only 22 minutes are now spent making calls and text messaging, with the remaining 83% of the time spent on mobile applications including internet browsing, social networking, gaming, and music listening (GSMA, 2013, 26).

Functionally, apps are many things: communication tools, entertainment platforms, information and learning devices. But fundamentally, they are products. They are products created and distributed on app markets, branded, and monetized through sales or ad-supported use. As of November 2013, the Apple iTunes App Store alone contained over a million apps and counting (Ingraham, 2013). The average smartphone in the UK contains 29 installed apps (“Our Mobile Planet,” 2013), each one serving different purposes and conveying different meanings to various segments of society.

As apps become ubiquitous and increasingly pervasive in all areas of life (health, beauty, entertainment, etc.), users may conceive additional motivations compelling use beyond functional. However, this remains a highly under-researched area of study despite the prevalence and proliferation of apps. The public use of smartphones creates an involuntary audience, where nearby viewers may decode these user interactions and users may consciously modify behaviour, particularly in the area of stigma. This interaction of use and perceived use then generates an internally negotiated space of identity projection and perception on the screen. The concept of apps themselves becomes tools to communicate facets of identity and become motivations to police identity.

This study investigates the conveyed meanings of app beyond functional purposes to show how some users use apps for purposes of identity projection and management, through means of self-presentation and image management, examining the specific issue of identity and perceived stigmatised sexual, gender, and racial identities. Drawing heavily from micro-functionalist approaches (Jacobsen & Kristiansen, 2010, 75) of self-presentation, this study explores the ‘communication-related practices’ that influence the conceptualization, experience and patterns of communication (Haddon, 2005, 9-10) in mobile app interaction in everyday life.

While everyday activity can be dismissed as minute moments of interaction, these moments illustrate an essential role in identity negotiation and self-presentation. For this study, this entails the negotiation of mobile apps as symbolic objects in the presentation of self. These moments reshape the conceptual nature of the human relationship to the app by reconceiving the way in which individuals use and perceive apps as part of public identity. This study situates its theoretical foundations in symbolic interactionism, and domestication and consumption studies, intersecting sociology, ICT domestication, and audience research, with Goffman’s dramaturgical model at the centre.

Literature Review

Theoretical evidence and substantiation of self-presentation and identity management through mobile phones (iPhones in this study) can be traced through the sociological history of symbolic objects and domestication literature, both of which have provided the basis for the analysis of mobile phone. While this review cannot encompass the entirety of the associated literature, it is a careful selection of the ones guiding this research study.

The Sociology of Identity: Symbolic Interactionism, Symbolic Objects, and the Presentation of Self

The role of perception and interaction with others (people and things) is fundamental to this study, providing insight on how interaction dynamics guide the sense of self. For the analysis of symbolic interactionism, the theoretical contributions of George Herbert Mead, Herbert Blumer, and Erving Goffman are particularly insightful.

For Mead (1934), humans communicate through an exchange of symbols to assist both the creation of reality and sense of self. Mead’s theory of identity recognition is especially pertinent, claiming, “we are more or less unconsciously seeing ourselves as others see us” (1934, 68). This dynamic of seeing ourselves through the eyes of others (the I/me dialectic) posits a notion of self that emerges through the internalisation of external views (me) and responses to these views (I) through the various contexts of social interaction. Consequently, this creates a complex formulation of self with multiple, genuine self-identities (Mead, 1934, 142).

Herbert Blumer then extended Mead’s theory, noting that the construction of objects is an interpersonal negotiation of meaning established within a shared society, thus brining in a communal aspect of identity negotiation (1962, 86). Both theorists place a large emphasis on individual agency to shape the “definition of a situation” (Scott, 2012, 119). Through shared interaction, individuals construct unique views of their sense of self, their sense of others, and the reality that surrounds them.

Erving Goffman’s particular angle of symbolic interactionism emphasises identity negotiation through a dramaturgical model. Where Mead outlines the processes of identity formation, Goffman presents contexts and motivations. Goffman’s notes a conscious construction of impression management, although he remarks a spectrum of awareness in the manipulation of identity for given audiences (1958, 10).

Goffman’s discussion of “teams” (1958, 50) relates closely to the group interaction outlined by Mead (1934, 164), showing how teams members are complicit in establishing a “definition of the situation” with a shared expectation of individuals and group presentation. The effects of team dynamics and impression management are highlighted when ‘incidents’ (134-135) occur, where information or gestures expose a portrayed identity as fraudulent. While teams are an important factor of impression management, rooted in Mead’s sense of self through the eyes of others, Goffman also addresses impression management to non-team audiences while at a close visual and hearing range of the individual (1959, 67). Crucially, Goffman offers specific cases of self-presentation with his 1963 study Stigma, analysing attributes of individuals that are disreputable by their social groups or society, rendering them socially rejected. Thus, at all times in public or front stage domain, individuals are performers complicit in impression management. It is not certain, however, if, individuals are necessary their true, backstage selves.

Mead and Blumer presented theories on how, through language and symbols, people establish themselves as individuals, while Goffman investigated the impetus to foster different senses of public selves in various situations. These two concepts are imperative in analysing human behaviour dynamics in presentation of self through mobile phones in order to identify motivating factors.

Taking up Goffman’s dramaturgical model and non-team audiences, Fortunati provides additional insight into social identity theory, mobile phones, and the presentation of self to argue the conception of mobile phones as backstage objects used in public spaces (2005, 205). Her analysis largely centres on the dynamics of public hearing of personal conversation on mobile phones (2005). This paper will also investigate whether smartphones, apps, and their use are even considered backstage arenas and activities. However, since her analysis focuses on public audiences perceiving mobile phone conversation, her study interviews audiences rather than the mobile phone user—or, performer (Fortunati, 2005, 214).

Consumption and Domestication Studies

Identity, however, has close links to the objects we use. Objects and technology extend identity-based theories to not only the interaction between individuals, but also the interaction of people and their belongings. As mobile phones are a commodified object as well as a social artefact, drawing from multiple disciplines is useful.

Consumption Studies

Consumption studies offer cogent analysis on social identity theories for this study, with focus on commercial interests and consumer behaviour psychology. This sector of research offers insight into the processes of identity formation and the role of the consumption of objects. Hirsch distinguishes between consumption and exchange theory, arguing that consumption differs from mere exchange by incorporating a level of social identity, bringing exchange into a social setting (1992, 210).

As Mead states that symbols take on a social meaning, consumer behaviour academics research the symbolic meaning (and imbuing of meaning) of objects and brands. Behaviour researchers Ritson, Elliott, & Eccles (1996, 127) also suggest that users can change the intended meaning of symbolic objects to their own self-constructs in a ‘resignification’ process, and these meanings are inconsistent among users. Dittmar contends that individuals use products and brand both to construct a sense of self, as well as to perceive the sense of others (2004, 6). Although Dittmar and and Ritson, Elliott, & Eccles refer mostly to branding products, latter discussion will show that this frame can also been applied to mobile phones. Oyserman (2009) proposes a theory of personal and social identity-based motivation (IBM) for consumption influenced by context and culture that can exemplify both desired and undesired identities. Thus, according to the IBM model, products used in a socially visible manner—that is, in public—are likely to engage users to consume such products for identity signalling, though signalling and interpretation is context-specific (Shavitt et al, 2009). This is particularly interesting in the case of apps, where certain apps consist of unique social networks and their meaning may not be necessarily ascribed by branding and logo, but from perception their own unique network within that specific app. That is, apps complicate the symbolic interactionism process by rendering each object, both within and external to the collective imaginary and fragmented into niche social groups.

The concept of possible selves (multiple conceptions of self) is also relevant in consumption studies (Markus & Nurius, 1986). Elliott, R & Wattanasuwan also suggest individuals have malleable identities contingent upon context (1998). This theory is consistent with Goffman’s “definition of the situation” (1959, 50) and Mead’s theory of multiple selves (1934, 142).

Domestication Studies

Where consumption studies explore the social psychology of object appropriation, domestication studies investigate the role of innovation adoption in everyday life. Early accounts of such domestic behaviour have come from the likes of Walter Benjamin, discussing appropriation of objects for representational value rather than functional, using the example of a book collection in his essay, “Unpacking My Library” (1969, 60).iiThis paper takes a specific interest in the branches of domestication literature as such that look at meaning and identity, and spatial placement of technology.

du Gay et al research technology as cultural objects, linking technology to culture through its capacity to forge a connection to distinct social practices, certain user groups, specific locations, and specific sorts of social profile or identity (1997, 10). Thus, the domestication of technology proves to move beyond functional adoption. Non-conventional and innovative uses of technology in the domestic sphere as they relate to identity raise question as to how and why technology should be used. The domestication of technology in households has been linked to the “moral economy”: adoption and use with the moral values of the family, bringing —originally—public values into a private space (Hirsch, 1992, 210). Silverstone et al note that the “appropriation of an object is of no public consequence unless it is displayed symbolically as well as materially” and investigates how placement within the household moral economy negotiates meaning (1992, 23). This moral economy constitutes four phases of domestication of technology: appropriation, objectification, incorporation, and conversion (Silverstone et al, 1992, 18). This framework of four phases, described respectively, views technology as cycle of integration into the everyday life, from its purchase, aesthetic integration into daily use, functional integration into daily use, and shift of meaning from private space to public (Ling, 2004, 20). Silverstone and Haddon later add the level of imagination before appropriation, whereby users conceive its integration into their lives before purchase through branding (1996, 63).

Silverstone and Haddon also argue that media and communication technologies have to have a function, whether they are intended by the designers or not (1996, 64). Their appropriation and functionality have multiple dynamics: use, location, or ownership. However, once mass-consumed and ubiquitous, the design and manufacture of these objects shift from promoting functionality to symbolic value (Silverstone & Haddon, 1996, 46). Livingstone adds that these symbolic values are to mediate between self, others, and the social context (1992, 105).

The role of space in technological adoption is a prominent theme in domestication studies. Individuals argue over ideal placement, depending on their own imperatives. Wheelock’s analysis of family dynamics among parents and children shows how the placement of technology engenders values and behaviours through placement (e.g. equality through communal placement) (1992, 100). Locating media technologies within the domestic sphere has symbolic, social, and functional elements (Quandt & von Pape, 2010, 342-343). While location can be used to control, as noted by Wheelock’s study, it can also be used for social functionality. Public space, on the other hand, involves many dynamics, including behaviour and etiquette (Haddon, 2000).

The analytical foundation of smartphone apps as cultural objects in self-presentation has roots in domestication studies and the analysis of digital objects as symbolic objects.

Mobile phones have become an increasingly researched topic in domestication. Haddon (2001) extended the domestication approach to ICTs outside of the home, referencing the mobile phone. Mobile phone domestication is a focal point for Rich Ling, whose works explore mobile adoption and their social consequences. His analysis of teenagers and mobile phones leads to the conclusion that mobile phones have roles beyond functional tools like coordination and communication, having a symbolic value representative of adulthood (Ling, 2004, 121) or even safety among female users when alone (Ling, 2004, 44). These two cases differ in their intentionality: representation of adulthood may or may not be intentional in Ling’s scenario, whereas representation of safety through connectedness has an intentional, specific purpose. Ling draws parallels to fashion and Goffman, where mobile phones can also establish identity and status through symbolic cues (2004, 105).

The concept of using products to construct identity crosses many disciplines. Aguado & Martinez go beyond McLuhan’s suggestion of technology being an extension of one’s body (1964) to suggesting that mobile phones are a part of the body, part of the “aesthetics of one’s personal identity” (Aguado & Martinez 2008, 8). Jenkins interprets Mead’s theory of interactionism as the ability to create meaning through the perception of an “environment of objects,” contingent upon individuals seeing themselves as objects (2008, 57). Thus, self-object and object extensions belong to a physical system of objects that as a whole create an identity. For example, mobile and general technology analysis have shown identity in gendered symbolic value (Wheelock, 1992; Cockburn, 1992). Lemish and Cohen highlight both hardware and software element to gendered dynamics, citing the technology as stereotypically masculine and certain uses (networking) as stereotypically feminine (2005, 191).

Mobile apps analysed as symbolic objects is under-researched—apps themselves being a relatively new phenomenon. Similar analysis can be derived, nevertheless, from other immaterial object. There exists evidence that digital objects are objects of symbolic value, used for self-presentation. The digitisation of cultural products does not necessitate a change in object uses, but simply poses new frontiers to self-representation (Larson et al, 2009, 25). Beer and Kibby allude to the likes of Walter Benjamin in their analysis of domesticated immaterial objects: digital music collections.

Authors have examined the particular challenges of identity in an immaterial space using digital music, where the older physical formats facilitated identity construction through physical proof. Beer offers an alternative form of symbolic value, where the interface (iPod) becomes the point of symbolism, offering representational value (2008, 83). At the time of the study, the iPod was a single purpose technology. On a smartphone, the comparable single-purpose interface /vessel is the app. Mere consumption of music “in the presence of others” is, at a basic level, a means of self-representation, although informants in a study by Larson et ll indicate other, more effective means (Larson et al, 2009, 23). Kibby’s response that music—like apps—is both an object and experience is particularly salient (2009, 431). Her study illustrates that users organise single digital music files into their own playlists, which provides them the opportunity to redefine a song within the context of its fellow playlist recordings (Kibby, 2009). Thus, the ability to organise files brings about a sense of physicality despite material presence forms part of the symbolic value to the user (Kibby, 2009, 441). Immateriality brings out a re-configuration or re-materialisation of self-presentation that is seen in material forms of symbolic interactionism (Beer, 2008; Kibby, 2009; Magaudda, 2011).

While analytical efficacy of the domestication framework is astute with new objects, Ling notes that its efficacy diminishes when investigating mundane objects (2004, 32). Domestication may not be adequate in analysis of the everyday negotiation process of everyday objects. This study explores the logic of locating mobile apps within the mobile screen space—apps that may or may not be new. A triangulated framework, combining the domestication approach with symbolic interactionism and consumption studies will ensure a holistic analysis.

Research Objectives and Statement

According to Goggin, despite the recent explosion of literature in mobile phone studies (Goggin, 2006, 4), the existing literature of mobile phones concentrating on the meanings and practices generated in everydaylife is sparse (2008, vii). With the prevalence of apps in society as a new phenomenon compared to mobile phones, it stands to reason that the literature on mobile apps in everyday life—particularly the mobile app screen space—is rather unexplored. The results and findings of this analysis can thus contribute to a better academic understanding of new media sociology.

This study is not only a question of whether self-presentation is a factor in how and why people choose and organise apps; but if so, what actions do individuals undertake to manage image and present the self:

RQ1: What symbolic meanings in the presentation of self do young adults produce through the collection, placement, and use of mobile apps?

SQ1: To what extent are users conscious of their impression management?

SQ2: Why and how do people manage their apps on the mobile screen space to present themselves socially?

SQ3: What are some of the underlying motivations to download applications, as they relate to how individuals wish to present and perceive themselves?

SQ4: How do people perceive the app collection and image of others?

Findings will also help address the question of the extent to which the dramaturgical model is useful in the context of smartphones and whether the conception of one true self is applicable.

Research Design and Methodology

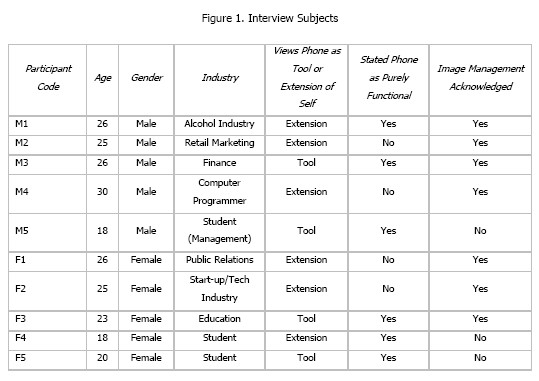

This exploratory study used semi-structured qualitative interviews and thematic analysis with a balanced selection of 5 male and 5 female subjects ranging from ages 18-26 in London, UK from July - August 2014. All interviews were conducted with written consent from respondents to record and publish quotations from the interviews, while ensuring their privacy and anonymity. As such, respondents have been coded by gender and number (e.g. Male Respondent 1 is coded M1).

Similar studies in self-presentation employed similar methodology. Qualitative interviews are primarily used in the above empirical studies: symbolic interactionism, consumption, and domestication. Considering the new territory of research in the presentation of self through mobile apps, detailed descriptions of individual views were necessary (Gill et al, 2008, 292). As such, semi-structured interviews were used to encourage discussion of the interviewee’s motivations and opinions of self-presentation in relation to mobile app adoption, collection, and management.

Other qualitative methods like ethnography and focus groups were considered but were inappropriate for the time frame and nature of discussion.

An initial pilot study conducted from March-May 2014 gave greater insights into the complexities in interviewee selection, topic guide creation, and thematic analysis and coding.

Interviewee Selection

Like the pilot study conducted prior to this report, discriminatory selection and quota sampling were employed to generate representative selections (Deacon et all, 2005, 52). There were intentional efforts to limit variables to try and keep the interviewing process consistent in gender, age, usage, phones, but varied in industry. Selections had equal gender proportions, limiting age to 18-26.

Gender was balanced for the purposes of equal opportunity of exploration and allow for potential gender motivations to manifest. Ling (2004, 44) noted variances in behavioural habits of females (safety) and Lemish and Cohen addressed gendered stereotypes in technology use. As such, maintaining equal proportions of genders was important in yielding the possibility for fair collection of gendered narratives.

Age has been intentionally selected based on previous studies, like the work of Ling (2004, 85), who additionally notes that that adolescence is a key time in identity formation, with a larger tendency to use objects like fashion and mobile phones to assert identity during this period. Phinney (2006), Arnett and Galambos (2003), and Arnett (2003) have all noted that identity formation continues well into emerging adulthood, inclusive of the 18-26 age range. A study in the UK by Green & Singleton targeted mobile users between 15-25, as the role of ICTs in young people’s lives, at the time, was under-explored (2007, 507). They also noted that mobile phones also played an integral part to the “sense of self” among this age group. Selection of an older audience is intended to increase the probability of length of smartphone ownership, purchasing power, and potential for more reflective capacity.

Selections were also limited to individuals who professed medium to high smartphone use (although usage is a subjective metric to each individual). The selection of iPhones for smartphones over Android was to maintain consistency in operating system layout and screen size (and impression management arena). iPhone screens all have the capacity to show 16-20 applications depending on model, in addition to the 4 apps on a bottom dock, or the fixed row of apps on all screens (“iPhone User Guide,” 23). iPhones, representing 32.1% (Page, 2014) of the UK market, have consistent layout throughout operating system versions and generally the same screen size (although iPhone 5s contain one extra row of four apps per page). Androids, representing 54% of the UK market, vary greatly in operating system layouts (Page, 2014). Global statistics indicate that only 17.9% of users use the latest version of Android (V 4.4 Kit Kat), and vary in screen size, ranging from small to x-large (“Dashboards,” 2014). At a device level, iPhones 5S and C cumulatively account for 21.1% of UK smartphone sales, while Galaxy S5’s only account for 9% (Williams, 2014).

While most interviewees were employed, the type of employment was a limiting factor in discriminatory selection, although it may impact findings. Participants were recruited through a snowballing effect (Deacon et al, 2007, 55) through the extended network of researcher’s environment, focusing on individuals with a higher net worth based on occupation. Thus, snowballing could be used to recommend interviewees that purposefully segmented in a variety of employment sectors (Gaskell, 2000, 42), including: students, public relations, entertainment, food and beverage, finance, and education.

Methodological Limitations

All methodological choices have shortcomings. Key problems with interviews include: interview response hindrances, interview bias, and coding bias. Interviews are subject to interview-response factors, where personal traits (e.g. ethnicity, gender, class) of the interviewer could compromise the interviewee’s answers (Deacon et al, 2007, 72). While building rapport prior to the recorded interview was attempted, interview-response factors can never be fully eliminated. Prompting stigma related questions could discourage responses in fear of judgement and entice interviewees to deliver socially desirable answers (Sudman and Bradburn, 1983; Deacon et al, 2007). Efforts were made to ease the interviewee into such topics through the use of question ordering (Deacon et al, 2007, 78); this too was addressed through rapport building. Questions were constructed with critical distance and the use of unknown interview subjects helped for both the interviewer and interviewee to co-create a meaningful text. Inconsistent information within the interviews was present, as subjects were not necessarily self-aware and cognisant of contradicting statements. Thus, there is an element of researcher bias in the re-interpretation of comments (Gaskell, 2000, 54).

Discussion and Findings

The following findings originate from the thematic analysis of the 5 male and 5 female semi-structured interview subjects in London, UK during July 2014. See Figure 1 for a breakdown of the interview subjects, where Participant Coding M/F denotes gender:

Thematic findings of self-presentation with mobile apps were present on both a reflexive level for the interviewee and upon strangers.

After coding and sorting key themes in interview transcripts, associations with impression management and perceptions of smart phones materialised. Respondents showed varying levels of awareness of impression management in their app usage-a spectrum noted by Goffman (1959, 11). All respondents viewed their iPhones as very personal objects, with differing perceptions of smart phones as merely a tool or, as many of them called it, an “extension” of themselves, echoing McLuhan (1964). While age was certainly a factor in terms of exposure to tech devices, it was neither a limiting nor determining factor. Those who saw phones as extensions were more aware of their habits as forms of impression management, be it defensive practices to safeguard their impression (Goffman, 1959, 7), or efforts to convey a specific image (Goffman 1959, 11). It is worthwhile to note that from the selection, five of the six respondents who cited their phones as being an “extension” of themselves discussed image management. Meanwhile only one of the four respondents who cited their phone as being mostly a tool described image management practices. While there is insufficient evidence to assert a correlation, this is certainly an area for future investigation.

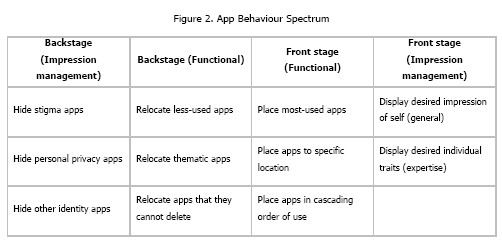

The following discussion of findings will centre on the respondents whose production of symbolic meanings veered towards the realms of projected identity and concealed stigmas. Interviewees displayed a wide spectrum of app habits and practices that could be categorised into two groups: functional behaviour and impression management (See Figure 2). This study will concentrate on impression and identity management findings, particularly on the construction of identity by both exhibiting apps of perceived benefit and hiding apps of stigma, in relation to sexuality, gender, and race. The quotations and analysis that follow were selected based on their ability to highlight key arguments in the presentation of self.

App Space for Impression Management

When pushed further on their app use and behaviours, some interviewees reflected and shifted their analysis of their initial functionality engendered behaviour towards impression management behaviour. Respondents M4, M5, F4, and F5, all of who were younger respondents, were more inclined to discuss functional metrics while older respondents discussed various tactics of impression management. Contrary to initial assumptions of younger age being more apt for identity formation, it was the older respondents who have owned smartphones for a longer duration that exhibited tactics of impression management in this limited sample study.

The most salient interview topic centred on the policing of identities, from the exhibition and concealment of certain facets of self. A few interviewees articulated a specific version of themselves they meant to show. They were, however, more forthcoming in their disclosure of hiding of apps to allow for the visual exclusion of any contentious, incriminating, salacious, suspicious, question-inducing app.

Impression Management: Projected Identities

Explicit discussion on social presentation was sparse—expectedly. Users were not as forthcoming in interviews about their own projected images (or perhaps not very self-reflexive) and those that responded did so at the end of the interview, upon self-reflection during discussion. The following examples are cases of impression management for the social presentation of an identity.

“But when people talk about it, it's like 'Yeah I have Twitter on my phone,' but I actually don't really use it. I guess that's a sense of me trying to be in the loop by showing that I'm up to date with technology… which I am, by the way!” – M1, 26, Alcohol Industry.“I have a close friend of mine who he's not a banker--he hangs out with bankers--but he's not in banking and he has a lot of banking apps on his phone. He just wants to fit in.” – M1, 26, Alcohol Industry.

“I suppose that I like being the one knowledgeable and current and ‘who knows [about technology],’ so I don’t delete any new app—or I guess it’s just an app at this point—off my phone, in case someone asks to use it on my phone. Like Uber. I downloaded it and never used it but then it became really popular in London and I use it a lot. Now I place it on the front.” – F2, 25, Start-up/Tech Industry

“First screen is the original one—I didn’t change it. It looks good already. It doesn’t ruin my mood at least so when I look at it, it looks good. […] I forgot to say, I am also a perfectionist. When you want to see everything in perfect, you see everything in order. So that’s how I am. […] The first screen was already perfect” – M4, 20, Student (Accounting)

“It’s kind of an indirect advice: Organise your phone! Please! That’s the advice I want to tell them—show them. But I don’t have rights for them. Everyone has their rights to arrange their apps, to arrange their phones: ‘it’s up to you.’ But that’s the indirect advice I can give them.” – M4, 20, Student (Accounting)

Management of the first screen often related to the projection of a desired identity or characteristic—a first impression, if you will. These cases illustrate the similarity of apps to branding, as a means to foster an idealised impression of self (Goffman, 1959, 42). In first three cases, respondents used apps and noted others’ use of apps to project an image of savant, though they did not use the applications (at least, not initially). The consumption of these apps (e.g. Twitter and Uber) is a manifestation of the motivation to maintain a desired impression. To this end, it also reflects Oyserman’s IBM based model of consumption: consumption to signal specific identities (2009). M1 and F2 had a desire to present a social self that was not necessarily genuine, but differed in their method. For M1, Twitter represented a symbolic meaning of being up-to-date with current affairs. While he confessed to not actually using the app, its mere presence on his second screen (claimed to be an extension of his first screen) created a veneer of his desired image. Moreover, M1 noted a friend’s use of banking apps to project an image. While this is perhaps an assumption, it also highlights a perceived assumption based on his own willingness to do the same for “being up-to-date”. F2 stored and collected apps without intimate knowledge of its use in anticipation of confrontation. Her vast collection of apps also helped to maintain a sense of ontological security in identity (Giddens, 1991), in the scenario where if her identity were threatened, the app would be easily accessible to show her currency in the tech sector.

Apps or the visual aesthetic of the app screen can also be used to highlight or spotlight existing personality traits. The first quotation from M4 attempts to exhibit an ideal self as perfect and organised. While impression management exists, it is less distorted than M1 and F2. What M4 shows is a conscious effort of an individual to present himself as organised, as opposed to respondents who discussed app organisational management as purely functional. Moreover, it is the general collection and organisation of apps that illustrate an identity than a single app as seen in the second quotation. For an individual like M4 who desires his “impression given-off” to be perfect, his app screen must be consistent with his projected self, thus maintaining his “definition of the situation” (Goffman, 1959, 53). While most respondents discussed individual apps as representative, M4 showed how an entire layout and screen could present oneself socially. Therefore, the configuration of applications can also promote a symbolic meaning.

Impression Management: StigmaWhere projected selves was one way to police identity, users equally hid facets of their app use and behaviour that were considered shameful or stigmatised. Defensive practices in impression management involved the concealment information, through the use of secondary screens and folders to hide applications from the first screen/front stage. M3 went as far as hiding apps within secondary pages within a single folder, as he maintained a single-page aesthetic with no secondary pages per se. While the action of hiding applications is similar, it is imperative to separate and analyse the motivations behind such behaviour. Motivations for hiding information differed and could be separated into sub-themes in relation to stigma: sex and sexuality, personal privacy, gender, and race.

Sex and sexuality

“I put Grindr and Tinder on my second or third page, just because I don’t want people to know I have it. […] I’ll also go through [the phone] of a friend of mine, and he has a bunch of gay dating apps—well, they’re not dating apps. They’re sex apps basically: Grindr, Hornet, Scruff. […] And they’re definitely on the second or third page of his phone.” – M2, 25, Retail Marketing“The Chive is a photo-sharing app. It’s slightly ridiculous, the app. It’s mostly got pictures of people doing stupid things and photos of half-naked girls.” – M3, 26, Finance, on explaining second page in a folder placement.

“The reason [for Tinder being on the second page of a folder] actually isn’t that I find it embarrassing because everyone I know has it—or everyone who is not in a relationship has it—it’s not a big deal. But if [friends] see it, their first thought is to open your Tinder so, ‘I can see your messages’ and that is something I am not willing to share. […] Tinder is something where they’re more curious about my dating life than my normal communications.” – M3, 26, Finance

“The last page [fourth page] is just bits and bobs that I don’t use too often, but don’t want them on my front page. […] The one app, Tinder, I don’t want people to see the first thing when I open my screen. […] It can be seen as—I don’t know... A lot of people don’t want people to know, like, their online dating. Especially if you’re always surrounded by people and strangers peering over your shoulder, left, right, and centre.“ – F1, 26, Public Relations

Certain applications users felt were inappropriate, of a stigmatised intimate nature, or very intimate were hidden: Tinder, Grindr, and Scruff. The examples above relate to such applications, where users felt that the public in London was not receptive to such app use—in public, at least. Where Silverstone et al through Giddens note that the purpose of domestication, particularly in the household, is to maintain a sense of social stability—or “ontological security" (1992, 16-17), this can also be applied through personal technological domestication to maintain stability of identity. Goffman (1959, 37) and de Beauvoir (1953, 533) also highlight the concept of identity stability as a motivator for impression management. Stigma, according to Goffman, then creates a rupture, discrediting attributes that maintain ones stable, social identity to one that is undesirable (1963, 13). As such, the internalised concept of a public image encourages people to create control over image and stigma. Goffman argues that stigma management may be heightened among strangers to avoid being subjected to unwanted responses, as intimate persons could be more understanding—though that is not always the case (1963, 68). Users like M2 and M3, consequently, felt obligated to hide such apps from public viewing.

This form of impression management ties closely with Goffman’s conception of identity, where individuals manage and hide their true, backstage selves (1959). Unlike Mead who states identity emerges through interaction, this specific scenario indicates a concealment of self rather than a negotiation. Stigma-related discussion surrounding online dating and sex apps like Tinder and Grindr were popular points of discussion among respondents. While some viewed the apps as still stigmatised, others like M1 saw them normalised and thus showed little motivation to manage its placement. This hints to Ling’s aforementioned critique of the limitations of the domestication framework, where the acceptance and decreased novelty of an object makes quotidian analysis difficult.

Unlike stigma apps where interviewees noted a general viewing public, certain applications can also be hidden from friends and known individuals to avoid the divulgence of personal information. M3 and F1 engaged in app hiding in anticipation of expected confrontational behaviour. Respondents M3 and F1 regarded themselves as rather private individuals, and thus, even within their personal social circles, concealed apps that ruptured desired social behaviour. Goffman notes that the goal of an individual—or performer—is to sustain the “definition of the situation” or his conception of a reality (1959, 53). The publicity of perceived private information can also cause dissonance in the social self and private self, thus also reinforcing Goffman’s conception of a managed self.

The increasing publicity and semi-public nature of phones and apps then further problematizes some of the technological sublime initially brought forth by hook-up and dating apps. Where apps such as Grindr were a private, virtual place for people to explore their sexuality (Blackwell et al, 2015, 1130) and maintain semi-discretion (Grosskopf et al, 2014, 512), users in this study become increasingly aware of the dismantling of their phone as a private space. Blackwell et al, whose study was conducted from 2011-2012, make particular note of the layering of public and private spaces, with the private use of mobile phones in public locations (2015, 1131) and the negative perceptions of Grindr (1134). The negative associations of Grindr and Tinder, combined with the public knowledge and use of such apps have pushed users in this study to monitor and alter their habits in a space once considered private.

While the resulting behaviour of impression management here is similar to the reaction to stigma apps and prevention of identity dissonance, the motivation to hide personal apps is not necessarily rooted perceived judgement or shame, but social norms. As Goffman notes, etiquette suggests that inattention can grant a sense of privacy to an individual (1959, 147). M3 and F1 anticipate audience reactions to largely private matters, and these reactions manifest themselves in their app management. Thus, if individuals assume audience behaviour or become their own audiences, protective practices may result.

Race and Gender

“I put [FoodGawker and Foodily] in my folder. I love them… but I don’t want to seem so Asian. […] No there’s nothing wrong with being Asian. It’s just, like, not me when I’m with them, you know? I don’t know. I can’t explain it” – F3, 23, Education“Yeah, [Instagram] is on my second page so my friends won’t see it right away. […] They all make fun of me for because they think it’s ‘girly.’ “– M4, 20, Student (Accounting)

Other defensive practices had more to do with maintenance of multiple selves and the management of racial- and gender-based identities. These comments partially echo the work of Mead, who noted that multiple identities and selves exist through a social process of self, whereby different possible selves emerge through interaction with different social groups (1934, 142). This differs from Goffman’s dramaturgical self, where a true self exists in the back stage, while different versions of self appear on the front stage (1959). These specific scenario falls between Mead and Goffman. While cultural selves shift among groups and contexts (Pollock and Van Reken, 2009, 60) and gender identities are socially constructed, both respondents did indeed show a concerted effort to manage their presented-selves and conceal some identity facets.

The first culturally motivated off-handed remark is cause for further analysis. F3, who saw apps as functionally managed, outline her one caveat: so-called ‘Asian’ apps. The association of food apps with being ‘Asian’ became an incentive to hide such a fact among her friends who would tease her for their perception of her identity dissonance. This highlights the symbolic value applied to and perceived from apps. The work of Pollock and Van Reken (2009) identified third culture individuals (TCIs)iii as having difficulty establishing an identity. When asked about their “ultimate” identity, individuals chose one identity one over the other (Pollock and Van Reken, 2009, 60); however, the mere question to select one culture over another is a leading remark and a pedagogical bias, presuming the existence of an “ultimate” identity.

Further research in TCIs shows how some TCI’s construct multiple selves that alternate in differing social circumstances (Moore and Barker, 2012). This later research resonates closer to F3’s action, exercising flexible multiple identities, although this process is concerted. The concealment of “Asian-ness” shows a growing area of further research among TCIs and their navigation and negotiation identity and stereotypes within ICTs and symbolic objects.

A study by Green and Singleton show how Pakistani-British youth perceive specific means of mobile phone use as gendered and ethnic. Her interview subjects discuss the role of specific phone straps differing from other socioeconomic groups, with their straps being an “Asian” ethnic identifier to symbolise ethnic and socioeconomic solidarity. Whereas Green and Singleton’s interviewees positioned themselves into an ethnic identity with mobile phone accessories, whereas F3 hides mobile phone apps to position herself away from a perceived ethnic identity. What was not explored but is a further point of analysis is whether this food app, for F3, has become a space for a third culture virtual community. Shuter conceives of a role for ICTs to engender third culture virtual spaces (2012). While his development cites more intercultural dialogue on platforms, TCIs to articulate themselves as a community, F3 uses mobile phone apps as an expressional outlet for her perceived Asian-ness.

Conceptions of gender and gender flexibility are also interesting. Although M4 does not necessarily view Instagram as girly, he has internalised his friends’ comments and conceded its status as ‘girly’ by moving it to the second screen. Like F3, M4 modifies his behaviour among peer groups, although to construct different gender rather than racial identities. Marrying Butler’s analysis socially constructed gender identities and gender performativity (1990) with Mead’s analysis of identity emerging through social interaction, one can argue how similar gender identities emerge through different social groups like the case of culture; however, additional empirical analysis is needed to substantiate further claims. Such app behaviour not only differs from the aforementioned categories by motivation, but also fundamentally in their theoretical underpinning of identity/identities.

However, related gender studies in technology show additional insight into M4’s behaviour.

Early mobile phone studies highlighted gendered disparities in mobile phone selection and behaviour. In Skog’s study (2002, 268), girls were likely skew towards symbolic representation for mobile phone selection and communicative for feature use, whereas boys chose mobiles based on functional use and for leisurely purposes. In analysing Instagram, females were more likely to use Instagram than males at a ratio 16% to 10%(Royal, 2014, 178). Where Instagram is a pictorial (or, symbolic) social network, the platform exemplifies both areas of gendered mobile behaviour. M4 echoes historic conceptions of gender and technology, which poses a challenge to his own masculinity. Royal suggests that since the telephone had been used for social purposes as female, stereotypically feminine technology are often seen as communicative and social, contrasting this with a males who embrace “geek” personas to signify social mobility through wealth (2014, 174-177). This view echoes Lemish and Cohen analysis of perceptions of gendered technology (2005, 191). Marwick describes how platform use by different genders creates perceptions of gendered technology (2013, 70). Thus, for a computer programmer like M4, this perception, particularly among friends, could cause a dissonance in projected identity from a geek to a social female.

Further Discussion on Impression Management

Perceived identities and projected selves with mobile phones seem to sink deeper into the operating system of the phone. Where studies showed mobile phone decoration and cases were once symbolic tools of self-presentation, customisation soon showed ring tones and wallpaper to exemplify self. It seems mobile phone apps, too, have been engulfed into the realm of identity and identity management.

The motivations for the collection and management of applications for self-presentation vary greatly, depending on whether and individual is revealing or concealing information. Although the method of concealment (via secondary pages or within folders) do not vary greatly, the motivations discovered through this analysis do change, spanning across topics of stigma, privacy, and multiple identities (gender and race). Pilot study analysis mostly indicated issues of stigma management, while this study also brought to light issues of personal privacy and multiple identity. Additional analysis would hopefully shed light on more motivations.

The policing of identities with regard to mobile phone use has been discussed by Walsh and White, whose study concludes that users generate a conceived notion of a prototypical user, and embody certain facets akin to their self-identity (2007, 2427). However, with mobile apps, where one behaviour can exemplify two characteristics (e.g. “tech savvy” but “too Asian” or “trendy” but “girly”), this compelled users of this study to both engage and hide. This in turn raises the question of how users perceive a “typical phone user”. Walsh and White even suggest incorporation of normative influences into “responsible use” of phones to reinforce responsible mobile behaviour (2007, 2427). This, however, has repercussions and visible effects for interviewees in this study, who feel they need to police their own behaviour identities relative to normative uses and normative identities.

Kinnunen et al (2011, 1071), referencing Nicola Green (2002), note the role of social and cultural factors, specifically citing gender, ethnicity, and sexuality in the consideration of time and space in mobile phones as they pertain to power relations. To this end, this studies along with its predecessors, exemplify how, among some users, identities or “social categories are performed, enacted and re-enacted” through mobile app adoption.

An overarching limitation in this section emerged as area for reconsideration and modification in subsequent studies: culture. The initial pilot study helped to provide discussion points and areas of investigation, but took place within the same culture as this study. Future studies ought to take into account the impact of the social setting of the interview, as well as the cultures of the interviewee. This will have an impact on areas of stigma, in association with gender, ethnicity, and sexuality.

What is particularly evident in this section are the additional requirements while employing micro-functionalist approach, whereby much of the analysis behaviour also relates to wider social, cultural, and even political structures that influence individual narratives. These discussions are not only insights into impression management practices, but also reflective of the values of a society and the identity components that individuals felt needed to be ‘managed.’ This also implies that the applicability of this study is socially and culturally specific. In addition to the previous variables that would impact findings, additional considerations include location of study, cultural association(s) of the respondent. Additional research into societal norms and stigma would benefit future researchers during the interviewing process to fortify ad-hoc question aptitude. While initial theoretical research included analysis in multiple selves, the results and discussion relating to the particular issues of concerted efforts of race and gender management were still unanticipated due to the exploratory nature of this research in this new field and insufficient emphasis of cultural sensitivities in theoretical research.

Impression management shed light on a host of issues relevant in understanding user perception. It is important to note that in some cases, in terms of patterns of behaviour and use, the app itself is less important than the perception of it among friends and the environment in which it is used. It was difficult to find appropriate conversation prompts as app perceptions differed greatly among interviewees. Moreover, the social contexts in which they envisaged app usage impacted their responses. It is important to breakdown the variables in what Woolgar (2005) and Pinch and Bijker (1984) describe as “interpretive flexibility,” the differing meanings individuals apply to a single technology. Silverstone et al (1992) and Silverstone and Haddon (1996) also integrate user interpretation in the domestication framework. The social context and circumstance has been a recurring theme interaction as well, including Mead (1934), Goffman (1959), Ling (2004), and Pollock andVan Reken (2009).

Additional Discussion on Functionality

Functional management, while seemingly mundane, is not completely devoid and separate from self-presentation and impression management. While not entirely unexpected, the lack of overt awareness and display of self-presentation seen in some respondents, particularly F3, was still surprising during the interview process. Challenging respondents without complicating discussion with theory posed a major challenge. Nevertheless, users’ functional placement and position of space still exhibited the creation of sense of learned “ontological security” (1992, 16-17). Using the example of bodily control, Giddens notes that mundane functional behaviour was at one point a conscious, concerted effort, and reinforcement of this maintains ontological security (57, 1991). As such, all of these functional behaviours were perhaps rooted long ago in an initial moment of identity construction, a moment where recollection of initial intentionality would be difficult to extrapolate during interviews. Thus, the topic of organisation (e.g. folders vs. screens) is hard to fully separate from impression management. Some users like F4 have no learned behaviour for app organisation, it seems more clear that at some point, interviewees chose to adopt such behaviour. Most respondents had a form of organisation, while M3’s extreme single-page layout with folders and no secondary pages interpreted as for both functional and aesthetic purposes. The theories of Giddens and Goffman highlight the lack of awareness and consciousness of impression management in everyday practice, as negotiated practices become reinforced as normal through repetition and routine.

Methodological Assessment

The findings discussed above are the result of two months of data collection and processing from semi-structured qualitative interviews from 5 male and 5 female subjects in London, UK during July and August 2014.

Throughout this study, there have been references to specific areas of improvement in greater detail based on improvements to the theoretical framework and methodological operationalization. On a general methodological front, there is also room for improvement: selection size and variable alteration.

Due to the time frame of this study, there were limitations in selection size and processing. As noted, further research is needed to expand the range of opinions and explore the possibilities of social variables impacting the outcome. The largest shortcoming of this research is the nature of methodology and small selection size, which do not allow for generalisation on a population (Gaskell, 2000, 41). A larger selection would show evidence of more patterns, activities, and behaviours that provide a basis for further research and investigation. It would be prudent to conduct a larger interview study to explore an even broader range of habits, which can then in turn be used as evidence to construct questionnaires.

This study was also limited to an analysis of iPhones, where interviewees were not specifically selected on diversity of culture, length of phone ownership, subculture membership, and awareness of impression management. With a larger selection size, future research can alter social variables to expand the range of perspectives, practices, and behaviours on self-presentation through mobile apps. Opening the selection size to Android, accounting for issues like version control, will also broaden the applicability of this study to the greater population.

Conclusion

With existing evidence of self-presentation in appropriated objects, technology, and specifically, mobile phones, this study contributes to the legacy of image management and provides support to its encroachment into the mobile app space. This study has attempted to extend the concept the presentation of self and identity in a new, mediated setting: mobile apps and the smart phone screen space. It has developed from existing literature in sociology, consumption studies, domestication studies, and mobile phone studies to explore the range of views and motivations underpinning impression management behaviours. While resources on the topic of smartphones and mobile apps were sparse, the literature of related studies was substantial and invaluable to the analysis of this study’s findings. Key theorists throughout the study include Goffman (1959; 1963), Mead (1934), and Silverstone et al (1992).

This innovative research yielded a variety of views and behaviours of mobile app usage self-presentation. Findings were extensive, but salient themes pertinent for further analysis were in specific relation to the explicit image management practices described by interviewees. First, users may attempt to evoke a specific image of self through the collection of mobile apps to maintain a consistency of persona, whether or not they even use the app. Second, users employ protective practices, like hiding apps on secondary screens and within folders, based on motivations like stigma, personal privacy, and multiple identity management. Third, users cast a wide range of judgement on others', constructing symbolic meanings from their app use, despite their inability to recognise their own participation in impression management activities.

After an analysis of transcripts and themes, it is evident that future research would require thorough analysis of cultural contexts. Cultural variations from an individual level, but societal as well, may impact the differing behaviours and motivations. An examination into the experience of technologically mediated self-presentation through the use of mobile apps would also be an interesting area of research, particularly to ascertain whether mobile apps differ from the motivations and experiences of other technologies. Apps are now closer to the body than ever, extending their reach into wearables with the proliferation of smartwatches. As technology becomes increasingly embedded into our lives a accessories, mobile apps become more personal and representational.

Other disciplines may use this evidence for further research and depart from theoretical analysis to praxis-oriented research, like consumer behaviour and user experience design. This has implications for balancing areas of convenience with user desire. While there is the convenience of search and visibility within operating systems, some users go to great lengths to hide such visibility. As mobile phones become increasingly public spaces, phones can reveal more than users want.

As objects dematerialise and convert into the mobile apps, sociological analysis of domestication and presentation of self will increasingly take place in the screen space. This analysis will hopefully provide a solid, preliminary foundation for future research in the production of symbolic meanings in the presentation of self through mobile app use.

Works Cited

Aguado, J.M. & Martinez, I.J.- (2008). “The Construction of the Mobile Experience: The Role of Advertising Campaigns in the Appropriation of Mobile Phone Technologies.” in Goggin, G. (2008). Mobile Phone Cultures. Sydney: Routledge. Pp. 1-12.

Arnett, J. J. (2003) “Conceptions of the Transition to Adulthood Among Emerging Adults in American Ethnic Groups.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2003(100), pp. 63-76.

Arnett, J. J & Galambos, N. (2003) “Culture and Conceptions of Adulthood.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2003(100), pp. 91-98.

Beer, D. (2008). “The iconic interface and the veneer of simplicity: MP3 players and the reconfiguration of music collecting and reproduction practices in the digital age.” Information, Communication and Society, 11(1), 71-88

Benjamin, W. (1969). “Unpacking my Library: A Talk about Book Collecting.” In Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books. Pp. 59-67.

de Beauvoir, S. (1953). The Second Sex. Trans. H. M. Parshley. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Blackwell, B., Birnholtz, J., & Abbot, C (2015). “Seeing and being seen: Co-situation and impression formation using Grindr, a location-aware gay dating app.” New media & society 2015, Vol. 17(7) 1117–1136. DOI: 10.1177/1461444814521595

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble (2007 Reprint). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cockburn, C. (1992). “The Circuit of technology Gender Identity and Power” from Silverstone, R and Hirsch, E (eds.), Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces. London: Routledge. Pp. 29-43.

“Dashboards.” (n.d). Android Developer Portal. Accessed 15 June 2014. Retrieved from http://developer.android.com/about/dashboards/index.html

Deacon, D., Pickering, M., Golding, P., & Murdock, G. (2007). Researching Communications: A practical guide to methods in media and cultural analysis. London: Hodder Arnold. [ Links ]

Dittmar, H. (2004). “Are you what you have?” The Psychologist. 17(4): 206-2011

du Gay, P., Hall, S., Janes, L., Mackay, H., & Negus, K. (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: the Story of the Sony Walkman, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Elliott, R and Wattanasuwan, K. (1998). “Consumption and the Symbolic Project of the Self.” E-European Advances in Consumer Research Volume 3, eds. Basil G. Englis and Anna Olofsson. Provo, UT: Association of Consumer Research. Pp. 17-20

Fortunati, L (2005). “Mobile Telephone and the Presentation of Self.” in Ling, R & Pedersen, P. (eds.) Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere. Springer-Verlag: London. Pp. 203 – 218

Gaskell, G. (2000) "Chapter 3: Individual and group interviewing." from Bauer, M. W. & Gaskell, G. (eds.), Qualitative researching: with text, image and sound. A practical Handbook. London: Sage Publications, pp. 38-56 [ Links ]

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204, 291-295. Accessed 15 July 2014. Retrieved From: doi:10.1038/bdj.2008.192 [ Links ]

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Reprinted 2006. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

“Our Mobile Planet: United Kingdom. Understanding the Mobile Consumer.” (2013, May). Google. Accessed 10 April 2014. Retrieved From http://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/omp-2013-uk-en.pdf

Goffman, E. (1959). ThePresentation of Self in Everyday Life, New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma, London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Goggin, G. (2006). Cell Phone Culture: Mobile Technology in Everyday Life. Oxon, UK: Routledge [ Links ]

Goggin, G. (2008). Mobile Phone Cultures. Sydney: Routledge. [ Links ]

Green, Nicola. 2002. ‘On the Move: Technology, Mobility, and the Mediation of Social Time and Space.’ The Information Society 18: 281–92

Green, E & Singleton, C (2007) Mobile Selves: Gender, ethnicity and mobile phones in the everyday lives of young Pakistani-British women and men, Information, Communication & Society, 10:4, 506-526, DOI: 10.1080/13691180701560036 [ Links ]

Grosskopf, N., LeVasseur, MT., & Glaser, DB (2014). “Use of the Internet and Mobile-Based “Apps” for Sex-Seeking Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in New York City.” American Journal of Men’s Health, Vol. 8(6) 510–520 DOI: 10.1177/1557988314527311

GSMA (2013). The Mobile Economy 2013. GSMA Intelligence. Accessed 20 April 2014. Retrieved From http://gsma.com/newsroom/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/GSMA-Mobile-Economy-2013.pdf

Haddon, L. (2000) ‘The Social Consequences of Mobile Telephony: Framing Questions,’ in R. Ling and K. Thrane, eds., The Social Consequences Of Mobile Telephony: The Proceedings From A Seminar About Society, Mobile Telephony And Children, Telenor R&D, Oslo.

Haddon, L. (2001). “Domestication and mobile telephony.” in Katz, J (ed.) Machines That Become Us, New Bruinswick, NJ: Transaction, pp. 43-56

Haddon, L. (2005). “Research Questions for the Evolving Communications Landscape.” in Ling, R. & Pedersen, PE (eds.) Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere. London: Springer-Verlag. Pp. 7-22.

Hirsch, E. (1992). “The Long Term and the Short Term of Domestic Consumption: An Ethnographic Case Study” from Silverstone, R and Hirsch, E (eds.), Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces. London: Routledge. Pp. 208-226.

Ingraham, N. (2013, Oct 22). “Apple announces 1 million apps in the App Store, more than 1 billion songs played on iTunes radio.” The Verge. Date accessed: 10 April 2014. Retrieved From http://www.theverge.com/2013/10/22/4866302/apple-announces-1-million-apps-in-the-app-store

“iPhone User Guide.” (2014, Mar 14). Apple Inc. Accessed 1 August 2014. Retrieved From: http://manuals.info.apple.com/MANUALS/1000/MA1565/en_US/iphone_user_guide.pdf

Jacobsen, M.H. & Kristiansen, S. (2010). “Labelling Goffman: The Presentation and Appropriation of Erving Goffman in Academic Life.” in Jacobsen, M.H. (ed.) The Contemporary Goffman. New York: Routledge. Pp. 64-97.

Jenkins, R. (2008). Social Identity. Third Edition. Abington, United Kingdom: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kibby, M. (2009). “Collect Yourself.” Information, Communication & Society. (12)3: 428-443. Accessed: 10 April 2014. Retrieved From: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rics20

Kinnunen, T., Suopajärvi, T., & Ylipulli, J (2011). “Connecting People - Renewing Power Relations? A Research Review on the Use of Mobile Phones.“ Sociology Compass 5(12): 1070–1081, DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00427.x

Larson, G., Lawson, R., & Todd, S. (2009). “The Consumption of music as self-representation in social interaction.” Australian Marketing Journal. 17(1). Pp. 16-26

Lemish, D., and Cohen, A. A. (2005). “Tell me about your mobile and I'll tell you who you are: Israelis talk about themselves.” in Ling, R & Pedersen, P. (eds.) Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere. Springer-Verlag: London. Pp. 187-202

Ling, R. (2004). The Mobile Connection: The Cell Phone’s Impact on Society. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.

Livingstone, S. (1992). “A personal construct analysis of familial gender relations” from Silverstone, R and Hirsch, E (eds.), Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces. London: Routledge. Pp 104-121.

Markus, H. and Nurius, P. (1986). “Possible Selves.” American Psychologist. Vol 41(9). Pp. 964-969.

Marwick, A. (2013) “Gender, Sexuality and Social Media.” In Senft, T. & Hunsinger, J. (eds), The Social Media Handbook. New York: Routledge, pp. 59-75.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mead, G.H. (1954). Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [ Links ]

Moore, A.M. and Barker, G.G. (2012). “Confused or multicultural: Third culture individuals’ cultural identity.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 36(4). Pp. 553-562. Accessed 12 August 2014. Retrieved From: doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.11.002

Oyserman, D. (2009). “Identity-based motivation: Implication for action readiness,procedural readiness and consumer behavior. “ Journal of Consumer Psychology,. 19(3), 250−260.

Page, C. (2014, Mar 31). “iPhone’s UK market share climbs while Android and Samsung see rare slump.” The Inquirer. Accessed 20 July 2014. Retrieved From http://www.theinquirer.net/inquirer/news/2337089/iphones-uk-market-share-climbs-while-android-and-samsung-see-rare-slump