Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.14 no.2 Lisboa mar. 2020

https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14220201602

Advertisements and Engagement Strategies on a Cross-media Television Event: A Case Study of Tmall Gala

Shenglan Qing*, Emili Prado*

*Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

ABSTRACT

Tmall Gala is a television event co-produced by Chinese internet company Alibaba and traditional television broadcasters to count-down for an emerging shopping festival: Double Eleven Shopping Festival. Mobile applications developed by Alibaba are applied as the second-screen for this television programme. This paper aims to study advertising strategies and audience engagement strategies on this cross-media television event, after the integration of internet technologies and companies into the cultural industries in China. Based on content analysis, we study general advertising tactics and the second-screen engagement strategies, as well as Alibaba's specific self-advertising contents in Tmall Gala 2018. This study shows that specific tactics are applied to avoid audience missing advertising information during the multitasking process. Alibaba's brand values blend with artistic performances and participative activities in the gala. These values legitimise the lifestyle relaying on e-commerce services and encourage users to subject themselves within the business of Alibaba. Finally, we argue that the ritual function of the television event does not disappear with the integration of the internet because producers can manage audience attention within the cross-media matrix. This case study can illustrate, on a global level, how a dominant internet company integrating with cultural industries, can embed its brand values in the consumerist culture in the society, which can, in turn, consolidate its infrastructural role in the internet macro-ecosystem.

Keywords: television events; media convergence; second-screen; television advertisements; Alibaba

Introduction

The global Internet world mainly consists of two macro-ecosystems: the United States-based ecosystem and the Chinese one. Despite the controversy between the ideologies, similar commercial logics can be noticed: dominant internet companies, which provide infrastructural internet platforms, expand to different economic niches and complete their own ecosystem, in which vast quantities of data are captured, analysed and commodified(Van Dijck, Poell, & de Waal, 2018) One of the strategies is to agree to partnerships with other platforms or "traditional" media organizations (Van Dijck, 2013; Van Dijck et al., 2018). This is seen as media convergence for media industries: The non-media companies enrol in the media industry and the acquisition of new technologies and new business models in traditional media entities (Karmasin, Diehl, & Isabell, 2016; Meikle & Young, 2012). Alibaba is a typical case in the Chinese ecosystem. This Chinese internet company started by managing e-commerce businesses and became a provider of infrastructural platforms, through which other online platforms can be built, and data flows are managed and processed (Van Dijck et al., 2018). Similar to other influential internet companies, Alibaba is currently expanding to cultural industries.

The second-screen has been introduced to television viewing with the rise of the Internet and computer-mediated technologies. It was initially considered distracting audience attention from television contents (Van Cauwenberge, Schaap, & Van Roy, 2014), but it also provides new meanings for television viewing. The second-screen becomes a forum for discussion about television, which engages audiences to participate in politics and raise the affective economy (Gil de Zuniga, Garcia-Perdomo, & McGregor, 2015; Kroon, 2017; Van Es, 2015; Wilson, 2015). Data generated on the second-screen also provide resources for audience analytics and commodification, which makes some television producers develop their own applications instead of using the third-party social media like Twitter (Lee & Andrejevic, 2013).

This paper is a case study on a television gala, Tmall Gala. It is co-produced by the internet company Alibaba and traditional television producers in order to count-down to the emerging annual shopping festival, Double-Eleven Shopping Festival, which was first launched by Alibaba. Alibaba also provides the second-screen applications and online streaming video platforms for the gala. This television program is a typical case to study media convergence in the Chinese television industry. This paper aims to learn about advertising strategies and audience engagement strategies in television content after the integration of internet technologies and companies. We also discuss the ritual function of this television gala and its social effects in this paper.

Based on content analysis, we study general advertising tactics and the second-screen engagement strategies, as well as specific self-advertising strategies of Alibaba's brands in Tmall Gala 2018. This study shows that producers try to schedule audience experience and manage "audience flow" (Caldwell, 2003) within the cross-media matrix. Specific tactics are applied to avoid audience missing advertising information during the multitasking process. Alibaba's brands are more integrated into participative activities and artistic performances rather than passive advertisements. This strategy enables the transmission of Alibaba's brand values through the ritualisation process. These values legitimise the lifestyle relaying on e-commerce services and encourage users to subject themselves within the business of Alibaba. Finally, we argue that the ritual function of the television event is not disappeared with the integration of internet, because producers can manage audience attention within the cross-media matrix. This case study can illustrate, on a global level, how a dominant internet company integrating with cultural industries, can embed its brand value in the consumerist culture in the society, which can, in turn, consolidate its infrastructural role in the internet macro-ecosystem.

Creating a Commercial Festival through a Media Event

Ritual communication has frequently been discussed in mass media studies, which mainly focus on the social effect of linear media. Carey (1989) proposes two ways of understanding communication: the transmission view and the ritual view. The latter understands processes of communication as ritualistic and dramatic acts, without denying the transmission of information. Dayan and Katz (1992) theorise the ritual function of media events. They argue that media events are remote and pre-planned ceremonies that take place in reality and are broadcast on television. Such media events intervene in the daily television flow and invite audiences to "stop their daily routines and join in a holiday experience" (p.1). Interpreting the theories of Dayan and Katz, researchers have discussed how the media event is a powerful instrument that can create social reality and help the authorities to achieve political or economic goals through performative, dramatised, patterned and scheduled content (Coman, 2005; Krotz, 2010; Liebes & Blondheim, 2005; Rothenbubler, 2010). Göttlich (2010) focuses on the new trend of advertising strategies involving reality television in the first decade of the 21st century. He argues that because of the commercial character of reality television, real life is ritualised and dramatised with commercial meanings in these types of programmes. Such ritual communication processes create social realitynew lifestylesamong some social groups.

Another factor that enhances the functionality of ritual communication is participation. Carey (1989) relates the ritual view of communication to "sharing", "participating", "association", "fellowship" and "the possession of a common faith" (p.18). Dayan and Katz (1992) point to how media events invite audiences to participate in the sense of media production and technological supports. They argue that television provides free and equal access for audiences to remote ceremonies. In this case, the home becomes a public space for ritual participation and celebration. Today, the incorporation of the Internet and mobile phones provides new ways to participate in television programmes and ritualise viewing process (Lee & Andrejevic, 2013; Van Es, 2015). Despite this, "audience participation" within the mainstream media context can still be subject to the control of the authorities (Andrejevic, 2007; Carpentier, 2011). In this study, we see the television gala as a kind of media event that ritualises festival celebration in Chinese society, and the performative, dramatised and participative content of the gala is programmed to invite audiences to the event and the festival's celebration.

The television gala has influenced Chinese society for decades in socio-political and socio-economic dimensions (Feng, 2016; Lu, 2009; Wang, 2010; Yuan, 2017). The television gala, as a kind of media events, provides broadcasters with opportunities to test new technologies (Dayan & Katz, 1992). The participative options supported by telecommunications had been programmed into the Spring Festival Gala for both political and economic purposes before the incorporation of internet companies (Lu, 2009). With the development of the Internet, sponsors and broadcasters have been discovering new advertising strategies. In 2015, the instant messaging mobile application WeChat, developed by Tencent, was incorporated into the Spring Festival Gala on China Central Television for the first time. Since then, APPs developed by Chinese Internet companies have served as cooperative second-screen platforms for the Spring Festival Gala. Some researchers argue that the usage of the second-screen in festival television galas provides a win-win multi-lateral model for audience, TV stations, and advertisers (Zhang, Wu, Qiao, & Wang, 2017).

Alibaba is one of the infrastructural Internet companies in China, and it has been expanding to the cultural industries for a few years. It initiates and co-produces the Tmall Gala to celebrate the Double-Eleven Shopping Festival on 11 November. This date had been known as Singles' Day, a part of Chinese sub-culture. Alibaba launched a shopping festival on its e-commerce platform Taobao Mall on Singles' Day 2009. With the rise of consumerism in Chinese society (Hooper, 2005; Meng & Huang, 2017; Paek & Pan, 2009), more and more people are celebrating this festival. In 2012, Alibaba separated Tmall (Taobao Mall) from Taobao and created two individual online shopping brands under those names. It was announced US$7.8 million in gross merchandise value for the shopping festival in 2009 [1] and US$30.8 billion in 2018 [2]. This shopping festival has become an influential commercial event in Chinese society and attracts large numbers of merchants and consumers. Since 2015, Alibaba started to co-produce and broadcast the annual counting-down gala with traditional television stations on the evening before 11 November to celebrate the shopping festival. The gala is called Tmall Double 11 Carnival Eve (天猫双11狂欢夜) and is also known as the 11.11 Gala or the Tmall Gala. Aside from the television content, two mobile e-commerce applications (APPs) Tmall, Taobao and a video APP Youku have served the second-screen function for this television gala providing supplemental information and purchasing links. In 2018, Zhejiang Satellite Television (ZSTV) and Dragon Television became the co-producers. It was reported that the two traditional channels that broadcast the Tmall Gala took an 18% market share and ZSTV took 12% of that figure. It therefore reached the top position of all programmes broadcast in the country at the same time. Moreover, Youku announced that 56% of audiences clicked the links promoted on the interface while they were watching the gala [3].

Television galas have created a socio-cultural practice in China that consists of celebrating festivals by participating in these galas, watching the performances and taking part in the participative activities, and this practice also produces political or economic meanings in the society. Achieving a high audience rating, the Tmall Gala also serves this ritual function of television galas in China. It invites audiences to stop their daily routines and to take part in the celebration by watching performances and participating in the activities through the second-screen. The theory of television event (Dayan & Katz, 1992) was firstly proposed in the time of "centred attention", and now it is applied in the time of "dispersed" attention (Sumiala, Valaskivi, & Dayan, 2018, p.181). In the next part, we are going to discuss how Tmall Gala creates the emerging festival and ritualises consumerism in Chinese society by designing a matrix of the second-screen and television.

Advertising on Television: From Television Flow to the Second-Screen

Williams (1975) theorizes the distribution of content on television as "flow", which consists of timed units programmed with specific meanings and values. Although the notion of television has been modified with the Internet (Gray & Lotz, 2019), we still understand the television as a kind of device that is supported by telecommunication or Internet technologies and provides audiovisual contents in the flow which consists of timed units programmed with meanings and values. Lee and Andrejevic (2013, p.41) argue that the second-screen is an idea that an interface can enable "monitoring, customization and targeting envisioned by developers and promoters of the interactive commercial economy" when the television is not considered as the primary interactive interface. It is proved that the second-screen can distract audience attention from television (Van Cauwenberge et al., 2014), but many researchers suggest that the second-screen can engage audience participation in both commercial and political activities (Gil de Zuniga et al., 2015; Van Es, 2015). There are two types of second-screen. The first one is the third-party social networking platforms, like Twitter, in which discussions and data are less controlled by television producers; another one is specific applications developed by television producers which can facilitate monitoring (Lee & Andrejevic, 2013). In this article, we define the second-screen as an Internet-based interface used in television viewing, which can reach commercial aims in television production by enabling audience participation. The question now is how do we consider the television flow first theorized by Williams (1975) after the incorporation of the second-screen?

Caldwell (2003) answered the question: "Programming tacticsadapted from old mediahave helped facilitate, prefigure and implement new-media development; but new-media technologies have in turn altered those same tactics" (p.142). He regards the programming strategies in television flow as "first-shift aesthetics" and the media convergence logic around television and the second-screen as "second-shift aesthetics". First-shift aesthetics engage the audience in the "ad-sponsored 'flow'" of a single television network through the organization of content along the timeline using different programming strategies. Second-shift aesthetics involve the multidirectional interplay of users and information, as well as the integration of media platforms and economic resources. Instead of the "flow" of timed content, the second shift concerns the "flow" of audiences between narrowcasting channels, platforms, and market niches. Second-shift aesthetics manage this audience flow by building brand awareness across the matrices of different media and scheduling audiences' media experience. Hayles (2007) puts forward two cognitive models: the deep-attention model, which refers to "concentrating on a single object" or "single information stream" for a long time; and the hyper-attention model, which is related to "shifting focus rapidly among different tasks" or "multiple information streams" and "having a low tolerance for boredom" (p.187). Based on the theory of "societies of control" (Deleuze, 1992), Avanesi (2018) interprets the theories of Caldwell (2013) and Hayles (2007). He suggests that the incorporation of the second-screen into television is "an iteration of an aesthetic of control" (p.15), from the deep-attentive model in the broadcasting era to the hyper-attentive model in the convergence era. The new aesthetic of control engages audiences in the matrix of media, technologies, and capital and commodifies them through "'self-managing' subjectivity" (p.15) within this socio-technical context.

Television advertising is a business model based on the attention economy (Davenport & Beck, 2001; Helles, 2016). Advertisements were initially programmed in the form of interrupting contents on television flow (Williams, 1975). With increasing competition between television networks and the development of technologies, audience attentions are dispersed, and advertisements show through "integration" and "co-production", which are also known as "product placement" and "branded content" (Hudson & Hudson, 2006; Jenkins, 2006). Third-party applications and "teleshopping" are also introduced in television advertisements (F. Jensen, 2005; Prado, Franquet, Ribes, Soto, & Quijada, 2007). Some researchers proposed typologies and genres of advertising modalities on television. Prado, Monclús, & Plana Espinet (2014) propose 12 advertising genres in television markets of Europe, included "mention", "product placement", "overlaid", "spot", and 10 advertising insertion modalities, included "isolated advertisement", "overlaid", "virtual embedded" etc. Jenkins (2006) studies 10 product placement formats in the co-produced reality show The Apprentice.

Various terms are used to describe the blurring of boundaries between entertainment content and advertisements, such as "advertainment", "branded entertainment" and "branded content". Jenkins (2006) argues that this strategy is "a collaboration between content providers and sponsors to shape the total entertainment package" to avoid audience skipping advertising information (p.68). For Simon Hudson and David Hudson (2016), "branded entertainment" is a sophisticated way of "product placement". They evaluate the integration of the advertisement from "low level of brand integration", which means passive "visual-only" or "verbal-only" models, to "high level of brand integration", which means "brand woven into the storyline" (p.495). They also suggest that "media used", "brand characteristics", "supporting promotional activity", "consumer attitudes to product placement", "placement characteristics" and "regulations" as key factors which influence the effectiveness of integrated advertisements. The aim of "branded content (or entertainment)" is to build emotional relationships between consumers and brands by intertwining advertising elements with the storytelling and entertainment contents (Hudson & Hudson, 2006; Lehu, 2007; Pino, Castelló, & Ramos-Soler, 2013).

In summary, the Tmall Gala is a television gala co-produced by Alibaba and television broadcasters. As a media event, it contributes to the creation of the emerging shopping festival in two ways. First, the gala intervenes in the daily television flow of traditional channels and invites audiences to watch it on either traditional television or online platforms. Second, the second-screen setting leads the audience to participate in the activities of the television event and make purchasing decisions on the second-screen. Both interrupt audiences' daily routines and draw them into the celebration of the shopping festival. Advertising elements are programmed into the four-hour cross-media matrix formed by the television flow and the second-screen.

Considering the innovative advertising strategies and the convergence of content, the second-screen and advertisements in the Tmall Gala, in the empirical part we are going to study advertising tactics and the second-screen engagement strategies on Tmall Gala (2018). Advertising forms and cross-media broadcasting strategies of Tmall Gala is changing every year. In 2018, this programme was broadcast on traditional television channels and the streaming video platform Youku. Audiences can enter into the real-time second-screen interface on APPs from Tmall, Taobao, and Youku by shaking the mobile phone in front of the screen of the live gala. The second-screen interface consists of performances, participative activities synchronised with the television flow and non-synchronised activities. In order to study how Tmall gala achieves its commercial aim by engaging audiences through the matrix of television and the second-screen, we propose the first research question (RQ).

RQ1: How are the dynamic relationships among the television flow, the second-screen and advertisements in Tmall Gala (2018)?

We split the RQ1 into three sub-questions which can conduct the empirical study to answer the general question.

RQ1-1: How are advertising contents programmed and integrated into the Tmall Gala (2018)?

RQ1-2: How does Tmall Gala (2018) encourage audiences to access the second-screen by programming and integrating related information on the television flow?

RQ1-3: How do activities on the second-screen synchronise with the contents on the television flow in Tmall Gala (2018)?

RQ 1 is proposed from the perspective of advertising and engaging tactics. Advertisements from different brands are put into the programme. As discussed before, content providers and sponsors collaborate an entertainment package is an advertising strategy (Jenkins, 2006). Tmall Gala is a co-produced television programme by Alibaba and traditional broadcasters, in which other brands also advertise in different forms. In this case, the role of Alibaba is "producing" a package of entertainment and advertising contents, while other advertisers are "adding" advertisements in the package. And the main objective of this gala is to count-down and warm up the Double-Eleven Shopping Festival. Thus, it is essential and interesting to know what exact values Alibaba produces in this gala and how Alibaba transmits his brand values through this process of ritual communication. We propose Research Question 2 (RQ2).

RQ2: How do Alibaba's brands advertise in Tmall Gala (2018) and how does Alibaba transmit its brand values through this media event?

Research Methods

The empirical research is based on a content analysis of the programme's four-hour television flow and we also apply participant observation on the second-screen. In the first step of data collection, the first author gathered the data from two places: the video of the Tmall Gala (2018) downloaded from Youku and the real-time interactive interface on the Taobao APP. For the part of television flow, the author splits and categorises contents on the video.

Considering the multitasking design of the Tmall Gala, we think it is essential to collect data on the second-screen. The first author carried out rapid online participant observation (Jorgensen, 1989; Millen, 2000) during the liveness19:30–24:00 (UTC+8) on 10 November 2018on the second-screen interface. The second-screen interface is instant for liveness, which cannot be recovered after the gala. The concept of rapid online participant observation combines theories on participant observation from Jorgensen (1989) and the concept of "rapid ethnography" proposed by Millen (2000), which provides a method for approaching "Human-Computer Interaction" in the context of "significant time pressures and limited time in the field" (p.280). The online observation was realised by participating in the instant activities on the second-screen of the Tmall Gala (2018) via mobile phone while the programme was broadcasting on Youku on a personal computer. The first author took notes according to the research questions during the participation. Screenshots of the second-screen activities (as well as a statement of the activities and commercial promotions published by programme producers) were obtained while the programme was broadcasting, which facilitated data gathering on the second-screen. In this study, the rapid online participant observation enables the author to collect data about participative activities for audiences on the second-screen.

After collecting the raw data, both authors re-observed the programme together and discussed the typologies and definitions of variables. To answer the RQ 1-1 and RQ 1-2, we propose typologies of contents in the Tmall Gala (2018) and, then, we use the typologies as variables for content analysis in order to study advertising and the second-screen engaging strategies in this programme. To answer the RQ 1-3, we combine the data from online participant observation and observing when the second-screen activities are synchronised with the programme and what kind of information simultaneously shows on the television flow.

In Tmall Gala 2018, some brands are owned by the Alibaba Group, some advertisers are part of the "Alibaba Ecosystem" and some have announced partnerships with Alibaba. We decide to focus on the brands, sub-brands and products belonging to the businesses and offerings of Alibaba. For RQ 2, we define the Alibaba brands according to the sections "Our Businesses" and "Alibaba Group Offerings" on the official website of the Alibaba Group (www.alibabagroup.com). These brands are Alibaba, Tmall, Taobao, Cainiao Network, Flypig and Ant Financial; the sub-brands and products are Tmall Supermarket, Tmall Global, Tmall Genie, Tmall Projector and Huabei. After defining the notion of Alibaba's brands, the first author returns to the video to observe and collect data for RQ 2. Then, both authors discussed the qualitative description from the data for RQ 2.

Typology of contents in the Tmall Gala (2018)

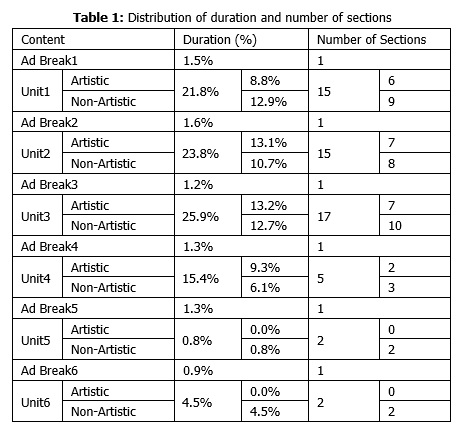

The duration of the entire video is 251'56''. We code the content in the programme according to the timeline and sort the content into artistic and non-artistic sections, and Ad Breaks. Table 1 shows the distribution of the duration and number of sections for each type of content in each unit. Ad Breaks are classic sequences of commercial spots surrounded by leads in/out of the gala. Artistic and non-artistic sections are alternately programmed from Unit1 to Unit4. The last two units only contain non-artistic contents. We identified 22 artistic sections and 34 non-artistic sections in the hole programme. Although there is a noticeable difference in the number of sections identified, the duration of artistic sections (44.5%) and non-artistic sections (47.7%) is almost equal programmed in the gala. Lastly, the total duration of Ad Breaks takes up 7.8% of the video.

The artistic sections consist of artistic performances like singing and dancing shows; the non-artistic sections consist of non-artistic performances in various forms. In the observing process, we find that non-artistic sections contain more information of advertisements and the second-screen. We therefore sort and name the non-artistic sections according to their performance content. We identified six types of performances among the 34 non-artistic sections according to their content: Gaming, Talking, Promotional Time, Coming-Up-Next, Isolated Spot and Jack Ma's Show.

• (Non-artistic) Gaming (five sections): In the non-artistic performances, there are five gaming sections programmed from Unit1 to Unit4. Celebrities form two groups and compete in each section. Audiences can participate in the synchronised activities of the games on the APPs and win prizes.

• Talking (19 sections): In the talking sections, presenters introduce the following performances and interview celebrities. They also promote advertisements and invite audiences to participate in the activities on the APPs.

• Promotional Time (three sections): Each of these sections promotes a specific brand and its products. Presenters invite audiences to access discounts on the brand on the APPs during the limited duration of each section.

• Coming-Up-Next (five sections): These sections are programmed before the Ad Breaks to present the shows coming up in the next units. The Coming-Up-Next sections are sponsored by a single brand: Mengniu Chunzhen Yogurt (蒙牛纯甄酸奶).

• Isolated Spot (one section): This is a short video of about two minutes that combines commercial and informative content and is programmed after an artistic singing section with the same advertising topic about China International Import Expo.

• Jack Ma's Show (one section): As the most famous co-founder of Alibaba, Jack Ma has his own show at the end of the gala every year. In the 2018 gala, he appeared in a short video rather than on stage.

Little research has focused on the recent tendency of advertising form in the television industry in China. Thus, referring to previous research on advertising forms (Hudson & Hudson, 2006; Jenkins, 2006; Lehu, 2007; Prado et al., 2014), we propose typologies of advertising modalities and the second-screen engagement modalities for this study. Advertising modalities are the ways in which advertising information is provided. Second-screen engagement modalities are the tactics used to encourage the audience to participate in activities on the second-screen. Logos of the APPs (Tmall, Taobao, and Youku) often show up together with the inviting information for the second-screen. We, therefore, consider the inviting elements of these three brands as second-screen engagement modalities rather than advertising modalities. Next, we are going to present the concepts we used to define the different variables. The advertising modalities are:

• Advertising Visual Patterns: These are visual patterns overlaid on the screen or embedded into the reality scene that transmit advertising information, according to the content of each performance.

• Advertising Verbal Patterns: Presenters and celebrities advertise by mentioning and listing sponsors and advertisers, introducing a product in detail or reciting brand values and slogans.

• Game Rewards as an advertising modality: In the gaming sections, promotions and discounts on advertised products are given as rewards to winners among the audience.

• Commercial Promotion as an advertising modality: Specific products are promoted in some sections and audiences can access information on the products during the limited duration of each section.

• Isolated Commercial Spot: Unlike the sequences of spots in Ad Breaks, this kind of spot is isolated or integrated into performances for specific advertising content.

• Product Placement: In this case study, we use "product placement" to refer to the advertised products exhibited on the stage of the gala. The products can be scene decorations, stage props, products in the hands of presenters or cartoon figures of products. Unlike branded content, product placement does not intertwine with storytelling techniques in the performances.

• Branded Celebrity: Some celebrities perform in the gala representing a brand. Their performances are not related to the brand, but these celebrities often give an advertising pitch before or after their shows. When they appear on the screen, their names appear overlaid together with the brand logo.

• Branded Content: Here, the advertising information, in the form of brand values or brand stories, intertwines with storytelling techniques in artistic and non-artistic performances.

The second-screen engagement modalities are:

• Inviting Visual Patterns: These are visual patterns overlaid on the screen that transmit the second-screen inviting information.

• Inviting Verbal Patterns: Similar to the inviting visual patterns, this refers to the ways in which presenters orally invite audiences to participate in the activities on the second-screen.

• Games as a second-screen engagement modality: There are five gaming sections in the non-artistic segments and three gaming sections in the artistic segments. Audiences are encouraged to participate in second-screen activities that are synchronised with the real-time performances during the limited duration of each section. We consider that these games serve a second-screen engagement function.

• Commercial Promotion as a second-screen engagement modality: When the presenters are promoting a product, they also encourage audiences to use the APPs to access commercial promotions during the limited duration of the section. We, therefore, consider that commercial promotion serves a second-screen engagement function as well as an advertising function.

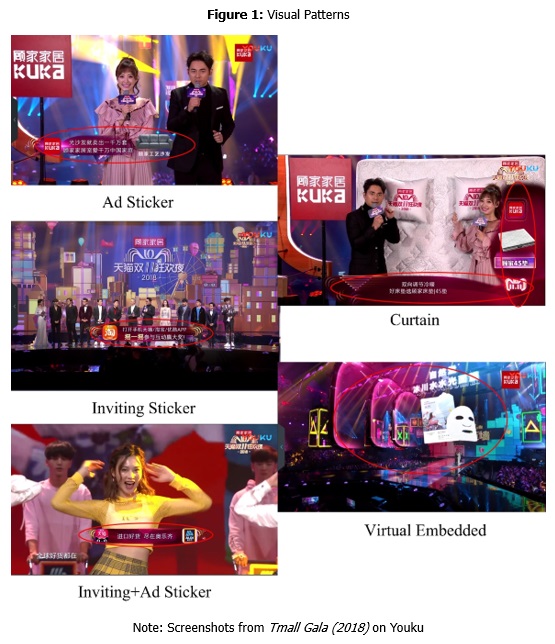

In the observing process, we find the visual patterns (Figure 1) are designed in different eye-catching levels and frequently appear transmitting advertising and/or the second-screen inviting information in explicit ways. We also provide typologies of visual patterns:

• Sticker: Stickers are comparatively small in size and they do not affect the visual experience of the performances on the stage. In this programme, we identified three types of stickers according to their advertising and inviting information. They are the Inviting Sticker, the Ad Sticker, and the Inviting+Ad Sticker.

The Ad Sticker serves an advertising function and contains the logo and slogan of the advertiser in the image. It does not invite real-time interaction, although sometimes the slogan encourages audiences to search for the brands online. The Inviting Sticker invites second-screen participation using the logos of the APPs and an inviting slogan: "Open the Tmall/Taobao/Youku APP, shake-shake, participate in interactive activities and win prizes." The Inviting+Ad Sticker serves both advertising and second-screen inviting functions. The logos of the advertisers and of the APPs are shown together. An advertising slogan and an inviting slogan flash alternately on this type of sticker.

• Curtain: This is a visual element that is overlaid on the screen in the shape of a curtain, which is more eye-catching and informative than the stickers. So, it could affect the visual experience of the performances on the television screen. This visual element provides alternating inviting and advertising information.

• Virtual Embedded: This refers to three-dimensional (3D) virtual images of promoted products that are embedded in the reality scenes of the gala. There is no second-screen inviting information in this pattern.

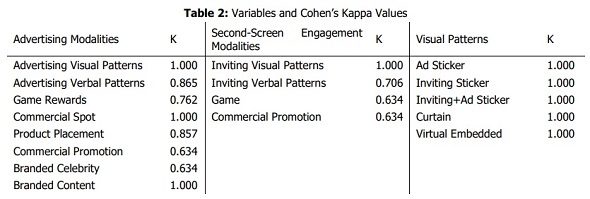

For the content analysis, we use these typologies as variables to study advertising strategies and second-screen engagement strategies in the gala. Two observers, who are Chinese native speakers and students in communication, are trained for coding. In order to cover all of the variables, we randomly select the Unit 2, from the Units 1-4 (Table 1), as the sub-sample of the reliability test, which includes 15 (27%) sections on the television flow. According to the Cohen's Kappa (Cohen, 1960), the highest Kappa=1.000, the lowest Kappa= 0.634, and the average Kappa value of the 17 variables is 0.866.

Data Analysis and Results

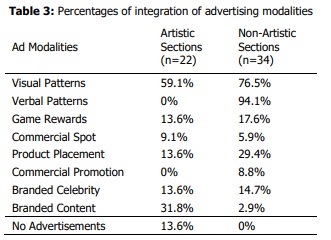

Table 3 shows the percentages of artistic and non-artistic sections that use the different types of advertising modalities. I n general, more advertising modalities are used in the non-artistic sections th an in the artistic sections.

Note: If a variable shows up once or more in a section, we count one in that section. An individual section may contain one or more variables, or it may not contain any variable.

There are 19 (86.3%) artistic sections and 34 (100%) non-artistic sections inserted advertising information. No commercial promotion or verbal patterns are used in the artistic sections. Branded content, a subtle and indirect form of advertising, is used more in artistic sections. Advertising prizes are given as rewards for participation in six (17.6%) non-artistic sections (five gaming sections and one talking section linked to the "final great prize") and three (13.6%) artistic sections.

We identified that the branded content modality is integrated into seven (31.8%) artistic sections and one (2.9%) non-artistic sec tion, which is the Jack Ma's Show. Three of the seven artistic sections tran smit the brand value of Alibaba and two transmit the brand value of Disneyland, Shanghai. There is one singing section advertising the China Inter national Import Expo, a trade fair promoted by the Chinese government, and another singing section that blends consumerist values with the lyrics and advertises the Aldi brand through visual patterns and prod uct placement modalities. We find three ways in which brand values intertwin e with the storytelling techniques of performances: (1) brand values are integrated into the lyrics of songs in artistic sections, for example, "good products from the world (…) to buy, to buy, to buy (…)", "(…) the Import Expo brings products from different countries (…)" and the gala slogan "more wonderfulness just started"; (2) cartoon figures play the protagonists in dancing shows, such as the cat from the Tmall logo and Disneyland's Micky Mouse (this differs from the cartoon figures used in product placement because the latter neither play the role of protagonists nor blend in with the narration of performances); and (3) stories are created for brands, mainly Alibaba, in the form of short videos.

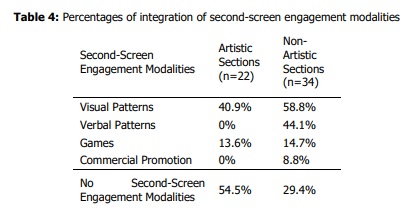

Table 4 shows the percentages of artistic and non-artistic sections that use the different types of second-screen engagement modalities.

Note: If a variable shows up once or more in a section, we count one in that section. An individual section may contain one or more variables, or it may not contain any variable.

There are 10 (45.5%) artistic sections and 24 (70.6%) non-artistic sections apply the second-screen engagement modalities. Similar to the data for the advertising modalities, the second-screen engagement modalities are more intensively integrated into the non-artistic sections than the artistic sections and no commercial promotion or verbal patterns are used in the artistic sections. Comparing the visual and verbal patterns in Table 3 and Table 4, we can see that advertising modalities are more frequently used in the gala than second-screen engagement modalities. The reason is that some sections merely transmit advertising information in a linear manner without encouraging real-time participation on the APPs. However, in the process of online participant observation, we found that second-screen activities involve more than what we learn from the television screen. As mentioned earlier, the second-screen interface can be divided into two parts: activities that are synchronised with the gala, and activities and performances that are not synchronised with the gala. The latter can also be seen as a strategy that engages audiences in the media matrix of the television event.

According to Table 3 and Table 4, visual patterns are the most frequently used modality for both advertising and second-screen engagement functions in both artistic and non-artistic sections. Combining data from the content analysis and online participant observation, Table 5 shows the percentages of artistic and non-artistic sections that use the above-mentioned visual patterns and which sections feature synchronous activities on the second-screen.

The most eye-catching visual patterns, Curtain and Virtual Embedded, which could impact the visual experience of the performances, are not used in the artistic shows. In contrast, these eye-catching visual patterns feature intensively in non-artistic games and promotional time, with synchronised activities intensively programmed in these sections.

Synchronous activities hold almost equal percentages in the non-artistic sections, 14 (41.2%), and the artistic sections, nine (40.9%). Among them two artistic sections and two non-artistic sections (one talking section and one gaming section) do not apply visual patterns which indicate the second-screen inviting information. It means that most of these sections (non-artistic 89.4% and artistic sections 77.8%) indicate inviting information on visual patterns to encourage audiences to participate in the synchronised activities on the second-screen. Comparing the data of each type of performance in Table 5, we consider that non-artistic games and promotional time demonstrate strong synergies between the second-screen and television flow. Intensive visual patterns are used in these sections to provide inviting and advertising information. Audiences are supposed to participate in the synchronised activities within the limited duration of each section. Such sections are programmed in each unit from Unit1 to Unit4.

Furthermore, we also find strategies that could be used to focus audiences on certain content or to avoid audience missing advertising information. As shown in Table 5, no visual patterns or synchronous activities have been found in the Isolated Spot or Jack Ma's Show, which transmit advertising information through storytelling techniques in short videos. Although intensive eye-catching visual patterns are programmed into the games sections, they do not disrupt audience attention in relation to the competitions. In the non-artistic gaming sections, the visual patterns often show up before the competition starts, while presenters are introducing the rules of participation and the game rewards. Similar techniques are found in the three music games in the artistic sections, in which audiences are supposed to play games on the APPs while artistic shows are being performed on television. Introductions to these games are included in the talking sections before the music game sections start. Table 5 shows that three of the talking sections use the Curtain pattern, which gives advertising and inviting information before each music game, without disrupting the visual experience of the singing shows or disrupting audience attention in relation to the game on the second-screen. The music games on the APPs are not related to the artistic shows in terms of content. If audiences want to enjoy or win the game, they must not focus on the television. When these shows are being performed, only an Inviting Sticker is overlaid on the screen. This means that no advertising information is given on television during the three music game sections. Advertisements appear in the form of rewards on the second-screen once each game is finished.

Alibaba's Self-Advertising Strategies

In order to study the self-advertising strategies of Alibaba in the Tmall Gala (2018), we focus on the brands, sub-brands and products of its main businesses and offerings as published on the official website of the Alibaba Group. The brands are Alibaba, Tmall, Taobao, Cainiao Network, Flypig and Ant Financial; the sub-brands and products are Tmall Supermarket, Tmall Global, Tmall Genie, Tmall Projector and Huabei.

The key findings of this part are: (1) The Huabei logo shows up once in the form of an Ad Sticker in one of the talking sections. A Tmall Genie product is presented and displayed in the presenter's hand during another talking section.

(2) Alibaba promotes the value that online shopping is a lifestyle and Alibaba is serving ordinary people. These values are integrated with its brands together into explicit or subtle verbal patterns in the talking sections, such as through oral presentations, for example:

"The Tmall Double Eleven Shopping Festival is a festival for ordinary people and for everyone."

This is also achieved through interviews with celebrities, for example:

"Do you do cyber-shopping in your daily life?"

"Well, I don't care much about shopping, but I have twins, they are seven years old and they love it, especially my son."

"What kind of things do they get?"

"Well, he basically gets everything he wants, games, all the time. But one thing he tried to do was to get a dog once. To order a dog (…)"

"I think Cainiao can send that."

(3) Tmall Genie, Tmall Projector and Flypig advertise separately as gaming rewards in three of the five non-artistic gaming sections. As we argued earlier, the non-artistic gaming sections, with eye-catching visual patterns, show strong synergies between the second-screen and the television. Tmall Supermarket, Tmall Global and Cainiao Network offer the "final great prize" jointly, which is presented at the beginning and the end of the gala. A huge truck carrying packages marked with the logos of these brands is placed on a sub-stage. This scene shows up on television whenever presenters mention the "final great prize". Only one lucky viewer among those who have participated in the games in the non-artistic sections can win the "final great prize".

(4) Alibaba's main business and brand values are also integrated into performances in the form of branded content. In the eight sections that use branded content advertising modalities, we find that four of them advertised Alibaba brands: three artistic sections and one non-artistic section. Two of the four sections are singing and dancing shows, in which lyrics and cartoon figures transmit the brand values; one section, called "An Ordinary Day" (平凡的一天), tells the brand story of Alibaba; and, lastly, the non-artistic section is the Jack Ma's show.

In the section "An Ordinary Day" (平凡的一天), the scenes of the singing show on the stage cross-fade with a video that tells a story about ordinary people's life experience in relation to Alibaba over 10 years. An interview with representatives of the ordinary people is programmed before this section starts. Similarly, the idea of respecting and serving ordinary people is also integrated into the Jack Ma's Show. The video tells a story about Jack Ma, the co-founder of Alibaba. He plays competitions with ordinary people who are specialized in specific jobs that are related to the businesses of Alibaba, such as packing delivery boxes, or selling lipstick as a video blogger. Jack Ma always fails in these competitions because he is not specialized in these jobs. At the end of the video, Jack Ma declares his admiration for ordinary people and emphasizes the mission and value of the Double Eleven Shopping Festival.

(5) Alibaba advertising elements are also integrated into the cross-media setting. According to the online participant observation, an interactive interface called "Double Eleven Time Machine" (双十一时光机) is promoted on the APPs several minutes before the section "An Ordinary Day". On the interface, audiences can consult their own 10-year shopping history on the Alibaba platforms. Each shopper's history is personalised using user-generated data from their accounts. Moreover, although we see the presence of the APPs in this programme as a second-screen engagement strategy, it is also a self-branding method for Taobao and Tmall, which belong to the main businesses of Alibaba, and for Youku, the video platform invested in by Alibaba.

According to Hudson and Hudson (2006), the key findings (1) and (2) deal with strategies involving a "low level of brand integration", with comparatively passive verbal-only or visual-only methods, while (3), (4) and (5) can be considered to demonstrate strategies involving a "high level of brand integration". Passive advertising methods are less applied than others to the brands of Alibaba. The brand values and products are more integrated into the participative activities and merged with artistic performances. This programming strategy can highlight some moments merged with Alibaba's brand value during the four-hour television show. In the programme, Alibaba mainly transmits values: online shopping is a ubiquitous lifestyle; Alibaba serves ordinary people; ordinary people, like users, merchants, and business partners, are great at incorporating the businesses of Alibaba. These values not only legitimise the lifestyle relaying on e-commerce services but also make ordinary people feel satisfactory to subject themselves within the business of Alibaba.

Discussion and Conclusion

Tmall Gala is a television event produced to celebrate the emerging commercial festival: Double-Eleven Shopping Festival. It ritualises the commercial event not only through the traditional logic of television event (Dayan & Katz, 1992) but also through the Internet devices and the second-screen (Avanesi, 2018; Caldwell, 2003). This television event interrupts audiences' daily routines and builds both commercial and festival awareness through the cross-media matrix constructed by television and the second-screen. The empirical section demonstrates that contents in the gala are programmed by specific strategies to transmit advertising information and engage audiences: (1) using visual and verbal patterns to indicate explicit information about advertisements and the second-screen; (2) integrating commercial elements into artistic contents, and dramatising advertisements in the non-artistic performances: this strategy transmits advertising information in subtle but emotional ways, which can engage audiences and increase advertising effectiveness (Hudson & Hudson, 2006); (3) synergizing programmed performances on television flow and activities on the second-screen, at same time, avoiding audience missing advertising information in multi-tasking process: this strategy schedules the audience experience and manages the "audience flow" within the cross-media matrix (Caldwell, 2003), in order to lead viewers to make purchasing decisions on the APPs and while building brand awareness. Advertisements of such cross-media television programmes are based on two commercial logics: the traditional attention economy logic, which means audience attention is attracted by advertising information and sold to advertisers; and the logic of the interactive commercial economy (Lee & Andrejevic, 2013), which means audiences/users' data are monitored and commodified on the digital platforms controlled by Alibaba.

We have demonstrated that Alibaba advertises its main businesses primarily through strategies involving a "high level of brand integration" (Hudson & Hudson, 2006), which emphasise and integrate Alibaba's brand values in some parts of the event. Strategies involving a "high level of brand integration" ritualise certain moments in the four-hour television flow and blend in Alibaba's commercial meanings. Alibaba expresses the ubiquity of its businesses and the appreciation to ordinary people in this gala, which deeply normalizes the businesses of Alibaba and encourages more extensive users to subject themselves within Alibaba's infrastructural platforms and to generate vast quantities of data continuously. The deep normalization and engagement can consolidate the infrastructural role of Alibaba in the Internet ecosystem of China.

In this study, we suggest that the theory on television events proposed by Dayan and Katz (1992) is still significant in the time of dispersed attention, because the television producers are able to draw audiences into a holiday experience by managing a cross-media matrix formed by television and the second-screen. Political power has a place in the television event, which can be seen in the integration of the advertisement in Tmall Gala 2018 for the China International Import Expo, a trade fair promoted by the Chinese government, in which Alibaba participated. The ritual function of the television event does not disappear. Tmall Gala contributes to the creation of the emerging Double-Eleven Shopping Festival, which involves the interplay of capital, technologies and socio-cultural practices and is endorsed by the political authorities and achieved through mass participation. Admittedly, the media effect on the festival's creation cannot be attributed only to the television event, but also to other forms of media like press and other social media platforms. Furthermore, from the perspective of the platform society (Van Dijck et al., 2018), we discuss that when dominant internet companies are expanding their own ecosystems in cultural industries, they can embed their commercial values in the consumerist culture in the society through the process of media convergence. It can, in turn, deeply normalize and consolidate the infrastructural role of these internet companies and their platforms in the macro-ecosystem of the internet.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2007). iSpy: Surveillance and power in the interactive era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [ Links ]

Avanesi, V. (2018). Second-screen subsumption: Aesthetics of control and the second-screen facilitation of hyper-attentive watching-labour. Convergence, 26(2), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856518781650

Caldwell, J. T. (2003). Second-Shift Media Aesthetics: Programming, Interactivity, and User Flows. In A. Everett & J. T. Caldwell (Eds.), New Media: Theories and Practices of Digitextuality (pp. 127–144). New York: Routledge.

Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as culture: essays on media and society. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Carpentier, N. (2011). Media and Participation: A site of ideological-democratic struggle. Chicago: Intellect. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7035-8_47-1 [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1960). A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

Coman, M. (2005). Cultural anthropology and mass media: A processual approach. In E. W. Rothenbuhler & M. Coman (Eds.), Media anthropology (pp. 46–58). California: SAGE.

Davenport, T. H., & Beck, J. C. (2001). The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Dayan, D., Katz, E. (1992). Media events: the live broadcasting of history. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. (1992). Postscript on the Societies of Control. October, 59, 3–7.

Feng, D. (2016). Promoting moral values through entertainment: a social semiotic analysis of the Spring Festival Gala on China Central Television. Critical Arts, 30(1), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1164387

Gil de Zuniga, H., Garcia-Perdomo, V., & McGregor, S. C. (2015). What Is Second Screening? Exploring Motivations of Second Screen Use and Its Effect on Online Political Participation. Journal of Communication, 65(5), 793–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12174

Göttlich, U. (2010). Media Event Culture and Lifestyle Management. Observation on the influence of media events on everyday culture. In N. Couldry, A. Hepp, & F. Krotz (Eds.), Media Events in a Global Age (pp. 172–183). London: Routledge

Gray, J., & Lotz, A. D. (2019). Television studies. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Hayles, N. K. (2007). The Generational Divide in Cognitive Modes. Profession, 2007(1), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1632/prof.2007.2007.1.187

Helles, R. (2016). The marketplace of attention: How audiences take shape in a digital age. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 32(60), 4. https://doi.org/10.7146/mediekultur.v32i60.23382 [ Links ]

Hooper, B. (2005). The Consumer Citizen in Modern China. Working paper No.12, Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies. Sweden: Lund University. [ Links ]

Hudson, S., & Hudson, D. (2006). Branded Entertainment: A New Advertising Technique or Product Placement in Disguise? Journal of Marketing Management, 22(5–6), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725706777978703

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press [ Links ]

Jensen, J. F. (2005). Interactive television: new genres, new format, new content. In Proceedings of the second Australasian conference on Interactive entertainment (pp. 89-96). Sydney: Creativity & Cognition Studios Press. [ Links ]

Jorgensen, D. L. (1989). Participant observation: a methodology for human studies. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Karmasin, M., Diehl, S., & Isabell, K. (2016). Convergent Business Environments: Debating the Need for New Business Models, Organizational Structures and Management respectively Employee Competencies. In A. Lugmayr & C. Dal Zotto (Eds.), Media Convergence Handbook - Vol. 2, Firms and user perspectives (pp. 49–68). Heidelberg: Springer.

Kroon, Å. (2017). More than a Hashtag: Producers' and Users' Co-creation of a Loving "We" in a Second Screen TV Sports Production. Television & New Media, 18(7), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476417699708

Krotz, F. (2010). Creating a National Holiday, Media events, symbolic capital and symbolic power. In N. Couldry, A. Hepp, & F. Krotz (Eds.), Media Events in a Global Age (pp. 95–108). London: Routledge

Lee, H. J., & Andrejevic, M. (2013). Second-screen theory: From the democratic surround to the digital enclosure. In Holt, J., Sanson, K. (Ed.), Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming, and Sharing Media in the Digital Era (pp. 40–61). New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203067994

Lehu, J.-M. (2007). Branded entertainment: product placement & brand strategy in the entertainment business. London and Philadelphia: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Liebes, T., & Blondheim, M. (2005). Myths to the rescue: How live television intervenes in history. In E. W. Rothenbuhler & M. Coman (Eds.), Media anthropology (pp. 188–198). California: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452233819.n18

Lu, X. (2009). Ritual, Television, and State Ideology: Rereading CCTV's 2006 Spring Festival Gala. In Y. Zhu & C. Berry (Eds.), TV China (pp. 111–125). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Meikle, G., & Young, S. (2012). Media convergence: networked digital media in everyday life. Basingstoke, Hamps: Palgrave Macmillan.

Meng, B., & Huang, Y. (2017). Patriarchal capitalism with Chinese characteristics: gendered discourse of 'Double Eleven' shopping festival. Cultural Studies, 31(5), 659–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2017.1328517

Millen, D. R. (2000). Rapid Ethnography: Time Deepening Strategies for HCI Field Research. In DIS '00 Proceedings of the 3rd conference on Designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques (pp. 280–286). New York: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/347642.347763

Paek, H.-J., & Pan, Z. (2009). Spreading Global Consumerism: Effects of Mass Media and Advertising on Consumerist Values in China. Mass Communication & Society, 7(4), 491-515. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327825mcs0704 [ Links ]

Pino, C. del., Castelló, A., & Ramos-Soler, I. (2013). La comunicación en cambio constante: Branded Content, Community Management, Comunicación 2.0, Estrategia en medios sociales. Madrid: Fragua. [ Links ]

Prado, E., Franquet, R., Ribes, F. X., Soto, M. T., & Quijada, D. F. (2007). La publicidad televisiva ante el reto de la. Questiones Publicitarias, I, 13–28.

Prado, E., Monclús, B., & Plana Espinet, G. (2014). La publicidad en la telerrealidad: nuevas formas publicitarias en la televisión del siglo XXI. In I. Fernández-Astobiza (Ed.), Espacios de comunicación: IV Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Española de Investigación en Comunicación (pp. 1329–1342). Bibao: Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación.

Rothenbubler, E. W. (2010). From media events to ritual to communicative form. In N. Couldry, A. Hepp, & F. Krotz (Eds.), Media Event in a Global Age (pp. 61–75). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203872604-14

Sumiala, J. M., Valaskivi, K., & Dayan, D. (2018). From Media Events to Expressive Events: An Interview with Daniel Dayan. Television and New Media, 19(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476417741673

Van Cauwenberge, A., Schaap, G., & Van Roy, R. (2014). TV no longer commands our full attention: Effects of second-screen viewing and task relevance on cognitive load and learning from news. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2014.05.021

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199970773.001.0001 [ Links ]

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Van Es, K. (2015). Social TV and the Participation Dilemma in NBCs The Voice. Television & New Media, 17(2), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415616191

Wang, X. (2010). Entertainment, education, or propaganda? A longitudinal analysis of china central television's spring festival galas. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 54(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2010.498848

Williams, R. (1975). Television: Technology and Cultural Form. New York: Schocken Books. [ Links ]

Wilson, S. (2015). In the Living Room: Second Screens and TV Audiences. Television & New Media, 17(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415593348

Yuan, Y. (2017). Casting an "Outsider" in the ritual centre: Two decades of performances of "Rural Migrants" in CCTV's Spring Festival Gala. Global Media and China, 2(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436417707325

Zhang, Q., Wu, C., Qiao, H., & Wang, S. (2017). No advertising, but more sponsorship? Chinese Management Studies, 11(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-01-2017-0001

Submitted: 8th November 2019

Accepted: 15th March 2020

How to quote this article:

Qing, S. & Prado, E. (2020). Advertisements and Engagement Strategies on a Cross-media Television Event: A Case Study of Tmall Gala. Observatorio, 14(2), 137-157.

Note

[1] Alibaba's Robust Ecosystem Supercharges 2018 11.11 Global Shopping Festival 10-year Anniversary of Global Shopping Festival Demonstrates Clear Upgrade in China's Consumption. Beijing. https://www.alibabagroup.com/en/news/article?news=p181019

[2] Alibaba Group Generated RMB213.5 Billion (US$30.8 Billion) of GMV During the 2018 11.11 Global Shopping Festival: Total GMV increased 27% compared to 2017. Shanghai. https://www.alibabagroup.com/en/news/article?news=p181112

[3] Data from Youku show 56% interactive audiences of the Tmall Gala directly participated in the Double11. (Original title in Chinese:优酷数据显示56% 猫晚互动用户直接参与天猫双11). Retrieved from http://www.techweb.com.cn/internet/2018-11-11/2711679.shtml