Introduction

Politics, as a human activity linked to obtaining and maintaining the resources necessary for the exercise of power over man (Bobbio, 2000), has in the creation of local power, a conception of democracy as a continuous process1 and close to the citizen, accompanying him in everyday life. The themes that local government is concerned with - garbage collection, street lighting, markets, works - are not fascinating. If resolved, they are of no interest to anyone; fail, and our lives become hell. Only when the pipes burst, the traffic exceeds the tolerable limit, the request for works remains in the drawer, does local power gain importance (Mónica, 1993).

Designed to play a central role in the tasks of development and democratic living (Ruivo and Francisco, 1999) between rulers and the governed, the Local Councils in Lisbon are in a political process of decentralization vis-à-vis the central power. A process that implies a simultaneous transition phase in the communication practice between stakeholders (politicians, journalists and citizens) involved in public governance policies. In this mediation of public visibility of public policies for local institutions, the communicative-relational interaction represents a vital need. Through the territorial strategic plan, which stands out as the backbone of proximity public policies, different lines of social, political and economic management are developed that should be translated into public communication messages through flexible and dynamic systematization.

The correct application of the processes, as well as the unity and coherence in the management of communicative and relational actions, ensures a precise orientation towards the objectives set by the municipal organizations (Campillo, 2010). This process of social reconstruction of governments, media and local communities, based on democratizing processes, triggering new effective and socially emerging forms of involvement and participation (Schmidt, Seixas and Baixinho, 2014), is undergoing a reconfiguration in which social media (Facebook) has played a role that is not yet widely studied in the digital public sphere of local government in Portugal.

This research arises from the interest in the study of strategic communication as a tool of political operationalization, in terms of the diagnosis of the territory and theoretical construction on digital communication in the local power of Lisbon. We start by reviewing the existing scientific production on strategic and political communication to identify, interpret and relate the structures and practices of political and strategic communication between politicians and citizens and the correlation with online involvement through the Facebook social network in the 24 Local Councils of our field of research.

As an academic contribution within the strategic communication applied to public institutions and their growing need for professionalization and improvement of communication strategies and production routines, we intend, based on the field research that will be carried out in this work, to map the communication in the local government, which may be a antechamber for other studies such as studies of reception of communication and participation of Lisbon residents, the local news scheduling in the media and the electoral and political legitimation through communication. A set of studies that can be replicated in other Portuguese municipalities, in a macro view of Portuguese municipal communication, similarly to Spain and the United States.

Local Power communication and the redefinition of the digital public sphere

In the dual exercise of communicating local government public policies, news happens in conjunction with events and texts. “While the event creates the news, the news creates the event” (Traquina, 1988), the role played by the primary definers is crucial. A group of which are the official spokesmen of power who, in a media-determined hierarchy of credibility, are recruited by journalists in the early stages where matters are structured (Hall et al, (1973; 1993). For this process of building the media agenda, with inputs and outputs from the political system (Wolfe, Jones and Baumgartner, 2013), there are promoters, producers and consumers of news (Molocht and Lester, ([1978] 1993) in an orderly continuity of power. A continuity of power that is going through a period of disruption by which citizens increasingly challenge the legitimacy of institutionalized politics and traditional media institutions, such as increasing voter abstention and the rise of cynicism and mistrust from the public.

Citizens are moving away from “high” politics and are increasingly organizing social and political meaning around their values and the personal narratives that express them (Graham, 2011) in alternative democratic strategies of media (Calhoun, 1992) in which citizen groups can influence the mass media, or they can establish alternative public spheres (Idem, 1992). Peter Dahlgren (2005) proposed the modern definition of the 'public sphere', describing it as a constellation of communicative spaces in society that allow the circulation of information, ideas, debates - ideally unrestrictedly - and also the formation of political will (that is, public opinion).

Starting from the public sphere2 as a place where private people come together as a public for the purpose of using argumentation for knowledge and critical discussion leading to political change (Habermas, 1989), the state tends to exercise control of this spontaneous flow of uncontrolled communication that is not motivated for decision making but for discovery and problem solving, and in this sense is not organized (Habermas, 1992). These processes of democratic formation of opinion and will (Idem, 1992) have undergone processes of public power intervention in the social sphere by publicly securing basic needs previously met by the family (Idem, 1989) and by controlling social duty: associations, clubs, communities and societies (Idem, 1989) and an insufficient vindication of this dispersed sovereignty of the people (Idem, 1992) by the media, caught between the contradictory effects of political influence and the weaknesses of economic survival (Idem, 1989).

For an evolution of the concept of public sphere of Jürgen Habermas, namely during the last decade of the last century, globalization contributed as a generalization of modernity (Giddens, 1991) and the existence of discursive arenas that overflow the bounds of both nations and states (Fraser , 2007), made possible through communication mediated by the internet and social networks that had a constitutive role in the development of global communication networks for individuals, organizations and movements (Slavko, 2010).

The national public sphere is transformed by a new dialectical relationship between supra and sub-national political contexts (Volkmer, 2003) and, as Fraser proposes, it is necessary to rethink public sphere theory in a transnational frame, whether the issue is global warming or immigration , women's rights or the terms of trade, unemployment or 'the war against terrorism', current mobilizations of public opinion seldom stop at the borders of territorial states (2007: 14).

As a result of globalization processes, in which the decisive locus of public affairs has shifted beyond the state to the world economy, world institutions, and a world polity (Sparks, 2004), with a dispersion of authority that explores the changing boundary between the state and civil society (Idem, 2010), we witnessed a reconfiguration of the sharing, among States, of many key governance functions with international institutions, intergovernmental networks and nongovernmental organizations (Idem, 2007).

The influence of digital communication in the reformulation of the Habermasian concept of the public sphere, through the denationalization of the communicative structure (Fraser, 2007), was felt in a simultaneous process of erosion of the power and influence of the state-based media on the one hand, and a parallel strengthening of both the local and the global media (Sparks, 2004).

However, Sparks argues, that talk of the erosion of the state-based public sphere from above by forces of globalization is at least premature and, at the present, quite mistaken. The old, imperfect, state-based public spheres are being eroded and new, albeit possibly even more imperfect, global and local public spheres are emerging, particularly around the new forms of the local (2004: 143). Among these new forms, we can find local power and its digital communication as means that can breathe civic engagement into an anaemic public sphere now dominated by official state actors, expert elites, and mass media, and thus strengthen its fourth and most vital component - civil society (Slavko, 2010: 37).

At a time when local government is being strengthened in its administrative and financial competences, and as its communication enters a process of reconstruction of the digital public sphere, we believe we are in the midst of a perfect storm for the professionalization of municipal communication consolidation of participatory democracy and full citizenship because only through effective public policy and best practice can we ensure that digital technology strengthens democratic institutions without undermining their fundamental objectives (Chester and Montgomery, 2017).

Local government manages life in society in its most varied dimensions of citizenship. Its existence was constitutionally established in 19763, and it wielded his power in the first municipal elections on December 12 of that same year. In the last five years, local government in Portugal, particularly in Lisbon4, has observed an evolution in its competences, having been granted a greater autonomy for the municipalities in the administrative governance of their territory.

In a logic of proximity, the closest political-administrative entity to the citizen is the Local Council5 and according to data from the Directorate-General of Local Authorities, Portugal has 3091 Locales, 24 of which are part of the municipality of Lisbon (Ajuda, Alcântara, Alvalade, Areeiro, Arroios, Avenidas Novas, Beato, Belém, Benfica, Campo de Ourique, Campolide, Carnide, Estrela, Lumiar, Marvila, Misericórdia, Olivais, Parque das Nations, Penha de França, Santa Clara, Santa Maria Maior, Santo António, São Domingos de Benfica and São Vicente), where more than 500 thousand inhabitants6 are concentrated with whom the Local Councils have daily to interact through analogue and increasingly digital channels in a dialogical communication (Kent and Taylor, 1998) which are constantly updated.

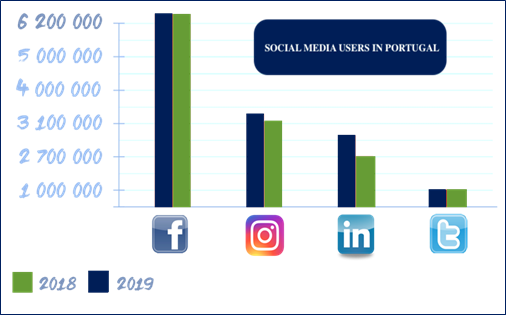

This continuous updating of the relationship between the state and citizens results from the possibilities offered by Web 2.07 and the intensification of civic participation through social media8 of which Facebook is the most relevant in Portugal. It had 6, 2 million users in 20189, and it has been used by local authorities to overcome communication barriers encountered in the public sector (Hofman et al., 2013).

Local Power: Strategic and Policy Configuration in Communication

Since the 1970s, municipal communication (Pérez, 1988; Camilo, 1999; Canel, 2010; Campillo, 2011) encompasses a set of activities, verbal or nonverbal, carried out by the municipality that aims to legitimize its values, activities and goals establishing a link between the municipality and the citizens (Camilo, 1999). It provides a connection in which communication is used as a form of municipal legitimation and justification that is not unrelated to the political dimension, since, similarly to municipal information, political communication also has an exclusively local scope, aiming at the legitimation of political criteria underlying the administrative options of the municipalities or the activities implemented by the mayors (Idem, 1999) and other social actors such as other politicians, communication managers, journalists and citizens.

This dialogue results in an exchange of messages that articulate in political decision making and its application within the community (Canel, 2006) in a circular and interactive relationship that occurs between the different actors involved (Idem, 2006) in various strategic actions that must be connected with political moments, serving to direct the power of planned, controlled and persuasive communication (Pérez, 2001; Hallahan et al., 2007) and fulfilling the mission that the political mandate requires through positive interaction with the public (Sung & Kim, 2014).

In the nature of strategic communication (Cornelissen, 2014; Hallahan et al., 2007; Argenti, 2005; Pérez, 2001), defined as the intentional use of communication by an organization to fulfill its mission, it is essential to determine that the institution's activities. In this case, those of a Local Council, they are strategic, not random or unintended communications - although the unintended consequences of communications may negatively affect an organization's ability to achieve its strategic objectives (Hallahan et al., 2007).

In these governance structures, communication is a management function that provides a structure and vocabulary for effective coordination of all media with the general purpose of establishing and maintaining favourable reputations with stakeholder groups on which the organization depends (Cornelissen, 2004) and with which it articulates strategically. This articulation is all the more significant if communication is defined as the constitutive activity of the social, economic and political administration (Hallahan et al., 2007) from a general set of communication objectives and programmes chosen to legitimize public policies and achieve their strategic positioning (Argenti, 2005) in the configuration of local power as a social and political market.

In this market, communication programmes must be strategically managed if the goal is to build long-term relationships (Grunig & Repper, 1992), relationships where the formation of attitudes precedes the behavioural intentions (Barreto, 2013) of the electorate, the preferred stakeholder, in a permanent campaign (Blumenthal, 1980) of conquest and maintenance of power. At this political dimension of the strategy (Lakoff, 2008), both public relations, and by extension, communication play a decisive role in identifying and diagnosing problems within organizations, managing external representation roles and the interrelationships between stakeholders, as well as the capabilities and competencies of the organization (Cutlip et al., 1994).

In this context, the organization is public, and its capacities and competences are in a restructuring mode that the Internet, as the fifth state (Dutton, 2009), allows in a kaleidoscope of globally expansive and temporally synchronous communicative networks, expanding the opportunities of connection between dispersed social actors (Blumer, 2013) in an exercise of citizenship for a digital democracy. Digital tools, such as social networks, are enabling other ways of engaging citizens in the life of their street, their city and turning them into active agents, reporting problems, identifying opportunities, proposing solutions for public intervention with the institutions of the city. This enables local power, combining interactivity from the properties of media technologies, with participation from social media protocols and practices (Jenkins, 2006), to achieve associative work made possible by interaction with entities in the public and private spheres from the comfort of home (Hjarvard, 2008).

The last few years have seen the power of the internet as a liberalizing, even destabilizing force, in the public manifestation of political communication (McNair, 2011) even in local government in Portugal. Over the course of three decades (1976-2006), local political realities, such as power, influence, authority, control or negotiation, have been exerted in a unidirectional and linear communicative sense until the end of the third era of political communication (Blumler and Kavanagh, 1999). These realities are now influenced by the effects of digitization of the public sphere in the fourth era of political communication (Aagaard, 2016; Blumer, 2013).

Political Communication in a social media environment

The mediatization of politics and the progressive digitization of the public sphere has resulted in the institutions creating a channel of direct and permanent communication with their public, especially with citizens. The institutions can provide the public with information while receiving their comments and opinions, all in a straightforward way, without the need for intermediaries (Castillo-Esparcia & Martínez, 2014) where the development of social networks as networked information services designed to support in-depth social interaction allows for greater proximity between representatives of local authority, particularly on social networks like Youtube, Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and more recently, TikTok10.

According to Stier et al. (2018), each Internet application has specific affordances and politicians demonstrate a strategic awareness of various communication arenas. In this case study, the Local Councils, in addition to Facebook, which is the digital social network chosen as the object of analysis, only resort to two other options: YouTube and Instagram. The presence on Twitter is almost residual, unlike local governments in Spain, and, for now, absent on TikTok, a social network that has international political communication11.

However, in the scope of our investigation, we consider Facebook to be the most politically relevant digital social network at the level of national local government, given the choice made by the Local Councils as well as the large number of residents who use the platform. However, the use of social media is dynamic, and its users migrate from one platform to another, in simultaneous consumption, or abandoning some as others become more popular. Given the simultaneous presence of most of the Local Councils on Facebook,

YouTube and Instagram12, one of the following lines of investigation may move towards a comparison

between the different degree of involvement seen in these social networks, seeking to reveal more refined resources in the metrics of care, such as the number of views or followers on various platforms (Nielsen & Vaccari, 2013). These specific mediation effects, both on YouTube and Instagram, need this analysis to be considered in the political communication models, currently developed in the local government. This underscores the need to argue with the utmost caution when trying to infer findings from one platform to “social media” as a whole, as it has often been done (Stier et al., 2018).(figure 1)

The Facebook Effect on the Reconfiguration of Local Power Communication

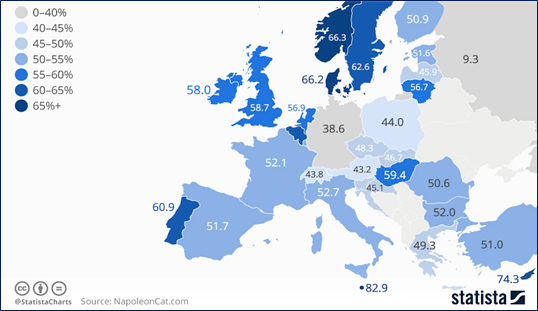

In Portugal, the option for Facebook is overwhelming with 6.2 million users in 2018, a trend that follows the rest of Europe15. Among these 60, 9%, 53% use this platform for reading, 29% for commenting and 49% for news sharing (Digital News Report, 2019), with an average involvement of around 3.1%.

Using Facebook16 as a communication strategy implies a daily use of the tools provided by the social network, accompanying the online community as a key factor in interacting with governments. In different ways, depending on the political instinct and professional experience of each media professional, everyone agrees on the benefits of social networking17. These are easier mass distribution of official website content, allowing users redistribute this content through their own blogs or social networks; and open corporate dialogue so that citizens have the opportunity to publish their own views on information distributed by local governments (Guillamón, M.-D.; Ríos, A.-M.; Gesuele, B. & Metallo, C., 2016).

The interactivity that disseminates information within the network through the likes, the share and comment options, which allow the user to attach a comment to the original post, as well as adding an image, video or link to another site, inside or outside the social network environment. Another attribute is political discussion through the exchange of ideas, attitudes, and arguments about governing choices and the performance of the elected, which encourages participants' action and motivation to express their personal political point of view, establishing relationships with people who are also interested in a particular subject and in the dissemination of information on this subject (Conroy et al., 2012).

Community monitoring following the page should also consider both the form and content of what is shared given the fact that it is difficult to ascertain whether citizens find the information useful without applying reception studies and categorizing the different interpretative strategies of citizens, the submission or opposition to information or a synthesis of contents made from their own interpretation (Hall, 1980). Benkler (2006) points out options for creating content that generates interactivity making it useful, entertaining readers, and reacting quickly.

Analyzing publicly available content on SNS such as Facebook has become an increasingly popular method for studying socio-political issues. Such public- contributed content, primarily available as Wall posts and corresponding comments on Facebook pages or Facebook groups, let people express their opinions and sentiments on a given topic, news or persons, while allowing social and political scientists to conduct analyses of political discourse (Stieglitz & Dang-Xuan, 2013).

The digital presence on the social network Facebook and its potential communicative effectiveness (McNair, 2011), as well as interaction with the users of the page, allows us to understand how Facebook can offer an opportunity to facilitate communication and interaction between government and society (Haro-De-Rosario; Sáez-Martín & Galvez-Rodríguez, 2017). This is in synergy with the content available on the institutional website, in line with studies carried out in other European countries, noting that in recent years, many municipalities have started using various social networks to communicate with citizens as an additional form of online communication (Idem, 2016).

Apart from the ubiquity of Facebook as the leading social network in online communication of these institutions, given the possibility of its being present in various networks, the adoption of one or more by a local government is a discretionary issue. Local governments should, therefore, consider the differences in citizen involvement found in each type of social network. If local government managers know which type of social network is most likely to achieve this citizen involvement, it will enable them to improve their communication strategies for social networks (Haro-de-Rosario; Sáez-Martín & Caba-Pérez, 2018), betting on the network that has the most return with its target audience and not being present in all networks. (figure 2)

Data Collection Methodology and Procedure

The main objective of this paper has been to document the evolution of the official Facebook pages of the Local Councils of Lisbon over the first 14 months of the political mandates legitimized by the municipal elections of October 2017. Having been selected the 24 that are part of the county, it was not possible to collect data from the Local Council of Campo de Ourique that deactivated its page in the social network and, for now, does not want its reactivation.

The combination of digital methodology (Rogers, 2009), used for measurement of dimensions, components and indicators in the use of social network made by followers aims to achieve the objectives of the work and the need to understand the current reality, working for the validity of the construction from the collected digital traces (Russell, 2013) providing new theoretical contributions to the object of analysis. We, thus, analyzed a universe of 23 pages using the FanPageKarma18 tool that, after presenting some problems in determining the percentage of the total performance of eight pages (Olivais, Parque das Nações, Penha de França, Santa Clara, Santa Maria Maior, Santo António, São Domingos de Benfica and São Vicente) led us to take another approach, through another tool used in the analysis of Facebook pages: Likealyzer19, maintaining and comparing the data from both. The documentary analysis of Facebook pages through selective archive and snapshots (Lomborg, 2014) allowed us to analyze expressions of the phenomenon without resorting to the intervention of the participants.

The construction of the digital map that we present, results from a longitudinal study of the performance of the Facebook page of each Local Council between November 2017 and May 2019. This performance (quantified by the number of views, likes, comments and shares) determines the degree of general involvement of the online community that follows each page. For the calculation of this involvement20, the interaction of the followers, calculated as the sum of tastes, sharing of comments and reactions to publications, contributes. As an evaluation tool for digital social networks, FanPageKarma enabled a detailed analysis of the metrics of each page, such as the growth of followers, the type and number of publications per day, the average duration of each of these publications, as well as the audience involvement. This average value of involvement21 is calculated by adding the total number of reactions to the total number of comments, divided by three, a result to which we add the total number of shares, multiplied by five and divided by the number of people who liked the page, during the time interval under analysis.

On the other hand, we use another tool to analyze digital social networks to complement and compare results. From the url of each page, LikeAlyzer allowed us to analyze and monitor the number of daily publications, the variation in formats (photo, text or video), the average size (for example, publications with less than 100 characters are considered better) regarding the reader's attention economy) or the native videos (inserted directly on the page, without an external link) as competing factors for the daily exercise of providing content. This collection of information on the response and digital interaction of the public on each page, enabled a final report to evaluate the key performance indicators.

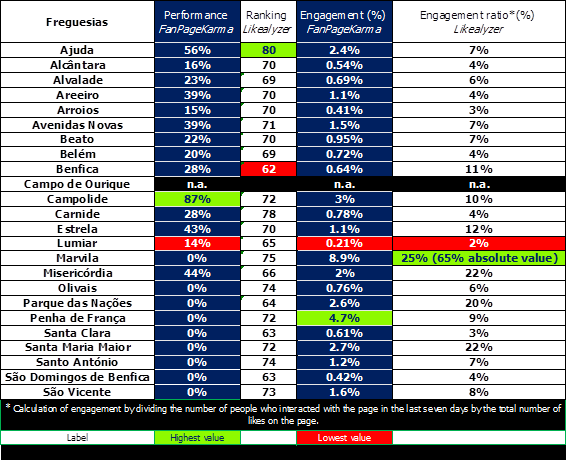

In the sample collected, we decided to compare the performance and overall ranking data as well as the degree of involvement expressed by the two tools for the same page (Table 1). Comparison was also possible in the metric of the number of daily publications of each page (table 2), as well as the percentage categorization of the type of post (photo, text or video only) in Likealyzer only.

Finally, we decided to make a comparison between registered voters, effective voters in the 2017 local councils and the number of followers of each Local Council's official Facebook page to understand the influence of the social network on a potential practice of democratic citizenship through digital communication. The internet, and specifically the social network Facebook, has added a new layer to political discussion and this implies understanding traditional political participation metrics such as voter participation (Ward & Gibson, 2010) in view of the social ubiquity of online participation, and its effects on the civic space and on the functioning of democracy (Dahlgren, 2015) in the physical and digital territory of Lisbon Local Councils.

Results Discussion: Performance, Performance and Engagement

The Marvila Local Council's Facebook page is arguably a success story, with an overall rating of 75 points and an 8.9% (FanPageKarma) and 25% (Likealyzer) involvement of 10,211 followers. Defining the political executive as a brand, the usefulness of the page lies in the possibility of interaction between the brand and its followers, which can lead to engagement (Barreto, 2013) that needs commitment to genuine and honest dialogue (Kent & Taylor, 2002) to go from the lowest hierarchical level of involvement (the click on Like) to the highest that implies defending the purchase of the product (Paine, 2011) which here is the vote of the voter who conquers and ensures the maintenance of power.

At the opposite end of the collected data, was the Lumiar Local Council Facebook page, with the lowest performance (14% according to FanPageKarma) and among the lowest ratings (65% according to Likealyzer) in the overall assessment within the universe of 23. These values are also frankly residual in the field of involvement (0.21% in FanPageKarma and 2% in Likealyzer) failing to mobilize its 9,884 followers. Another case that deserves special consideration is the Campolide Local Council Facebook page with very satisfactory performances with the highest level of performance (87% on FanPageKarma) and one of the highest overall page rankings (72% on Likealyzer), reaching optimal levels of engagement (3% in FanPageKarma and 10% in Likealyzer).

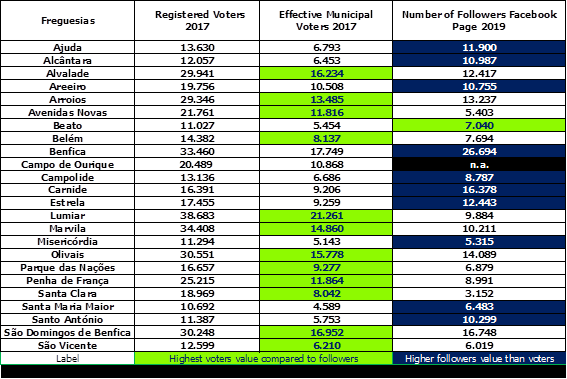

Table 1: Local councils from lisbon municipality | November 2017 - May 2019

Source: Constructed from data collected (01.11.17 | 31.05.19) in FanPage Karma and Likealyzer applications.

It is also noted that it is the only page among the 23 analysed that offers its 8,787 followers the possibility of direct interaction with the president, André Couto, through Lives, fulfilling principles such as mutuality, proximity, empathy, risk and commitment (Kent & Taylor, 2002) in the dialogue between the citizen and the politician. In 2016, Fernando Medina was the first politician in local government to use this symmetrical communication resource between rulers and the governed, aiming at transparency of information and accountability in the situation of Carris (Lisbon transportation company) and its transition to the management of the Lisbon City Council22.

With regard to this communicational device used by both politicians, we must consider expressions of two general processes, which act together, but which are based on principles of different natures, persuasion and seduction. Persuasion to gain the conviction of the audience through rational arguments, namely through the detailed presentation of the candidate's programme, and seduction, which operates in an artificially created spectacle scenario, where the politician is the protagonist (Ferreira, 2016: 58).

A logic of conversation and participation that, in our view, should be followed by the other pages and confirms that social networks are not about technology, but about people (Barreto, 2013) who, as participants, are encouraged for learning, considering and expressing their political and personal point of view (Conroy et al., 2012).

Discussion of Results: Number and Categorization of Publications

In a brief and essentially exploratory case study, we also want to measure the daily averages of government publications and the way they are used according to the categories of photography, video or just text, as the analysis of publications and the properties of those publications convey an approximate image of how local governments interact with their citizens on their Facebook pages (Hofmann et al., 2013).

In the field of daily publications, we return to Marvila which leads with 6.4 publications (FanPageKarma) and 4.2 (Likealyzer) in both analysis tools used. And, finally, we also found Lumiar's Facebook page that barely reaches a daily average of publication (0.5 on FanPageKarma and 0.9 on Likealyzer), which confirms an obvious urgency in the strategic repositioning of this Local Council's digital communication. A potential risk may lie in the disruption of the political cycle where 'informal opinion formation generates' influence'. Influence is transformed into 'communicative power' through political election channels and communicative power is again transformed into 'administrative power' by law” (Habermas, 1996).

On the Facebook pages we reviewed, visual category publications using photography dominate with values above 90% in Alcântara, Areeiro, Olivais, Parque das Nações and Santa Clara while in Beato the lowest value (15%) is opposed by a massive use of video (82%), a possibility completely rejected by the pages of Santa Clara and Lumiar. The case of Lumiar offers a new angle of analysis, i.e. not making videos available, betting significantly on photography (86%), which in itself does not translate into satisfactory results, as we saw earlier. It is important not only that governments communicate with citizens, but how they communicate is also important and, in particular, how citizens perceive such communication (Bruns & Bahnisch, 2009)23.

Discussion of Results: Registered Voters, Effective Voters and Followers

In the municipality of Lisbon, where more than half a million inhabitants are concentrated, more than 240 thousand did not vote in the last municipal election in 201724, which led us to compare data from registered voters and effective voters with the number of followers on official Facebook pages of each of the Local Councils to gauge the degree of integration of the citizens in the political process, by joining the Local Council page to where it exercises the vote.

The number of followers, more importantly than the number of people who just like the page, is an essential value in a page's success metric. The more people who follow a local government's Facebook profile, the greater the opportunity it has to build relationships with the population (Haro-De-Rosario; Sáez-Martín & Galvez-Rodríguez, 2017) so that, after the elections are over, there is no disruption in communication that can be interpreted as inactivity by public authorities (Moreno, 2012) until the next election cycle in 2021. This is an interpretation that may disturb the perception of the message during the political term and influence electoral participation and full exercise of citizenship.

Among the Local Councils with more citizens following the local government's Facebook page than citizens who exercised their voting rights, we find Benfica (26,694 followers to 17,749 voters in an electoral territory with 33,460 registered) who leads a group where Ajuda, Alcântara, Carnide and Campolide have more followers than voters in municipal elections.

The highest voting level in 2017 was reached in the Local of Lumiar, with the participation of 21,261 voters out of 38,683 who could have done so. As we saw earlier, Facebook page analytics results are far below average for all Locales in terms of the performance and engagement of their 9,884 followers. We empirically believe that, in a Local with such low abstention, the level of politicization is high, which makes the work of diagnosing and restructuring the social networking page even more urgent strategically to reach over 10,000 potential followers ( looking at the voters) or over 20,000 (looking at the registered voters) and recruiting them to join the group. Conroy et al. (2012) found that political groups on Facebook increase political participation outside their members, making groups the ideal tool for increasing and strengthening public involvement in government development - the fundamental principle of democratic government.

Conclusions

Governmental communication in local government and its strategic conception, in the media ecosystem of the new forms of relationship provided by social networks, is a structural element in the process of conquering and maintaining the governance and democratic legitimacy conferred by the electoral mandate.

In order to achieve results in the political narrative that the chronology of a mandate presupposes, in fact, digital communication is crucial, demonstrating its importance at every moment when citizens face everyday problems where the rapidity of the Facebook social network can help to simplify the chain of procedures until a possible solution to the question raised by the citizen is found.

In the specific case of each local government's official Facebook page, a strategic approach is vital through a system of monitoring and reviewing social and political objectives, along with a systematic collection of data (either through the internal tools available on the social network). External ones (like the ones we use) that can lead the process of prioritization and consequent decision making (Bilhim, 2004) of the content and the most efficient and appropriate categories to make them available to the consumer of your social network.

Online communication, specifically the use of Facebook in communication between the Local Council and the citizen, still has a long way to go to fill in new forms of political participation, the continuity of the traditional public sphere in the online environment and the building of a democracy in a proposal that looks at technology head-on, taking on its political character unambiguously, and which in particular identifies on the Internet as an important potential for deliberative political communication capable of generating new forms of democratic life (Esteves, 2011), besides the Facebook citizen who does not extend his citizenship from mobile phone and computer to the voting booth.

“Digitally equipped, monitoring and voyeuristic, motivated and apathetic, the liquid citizen flows in a fragmented continuum, but does not anchor” (Papacharissi, 2010) which may imply a peculiar paralysis of civil society (Habermas, 2006) meanwhile fought by a media culture that try to anchor the citizen in discursive spaces in social networks.

Facebook as one of the contemporary mirrors of politics and politics, which we intend to analyse in our doctoral thesis in the period until the 2021 election cycle, can realize a digital public sphere that also needs the solidary spirit of cultural traditions and standards (Habermas, 1992) to achieve and promote a more transparent, rigorous and efficient democracy with real input from all.