Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Angiologia e Cirurgia Vascular

versão impressa ISSN 1646-706X

Angiol Cir Vasc vol.11 no.1 Lisboa mar. 2015

CASE REPORT

Vegetation in an ascending aortic graft: Three major complications in vascular ï¬elds -Case report*

Vegetação em prótese da aorta ascendente: três complicações major em territórios - caso clÃnico

José Almeida-Lopesa,*, Armando Mansilhaa, Dalila Rolima, Paulo Diasa, José Ramosa, José Teixeiraa

a Department of Angiology and Vascular Surgery, São João Hospital, Porto, Portugal

ABSTRACT

The authors describe a rare case report of a septic embolism to a lower limb, a mycotic superior mesenteric artery aneurysm and a hemorrhagic stroke derived from a large mobile vegetation in an ascending aortic graft.

Infected ascending aortic grafts should be handled with a high level of suspicion, always bearing in mind that the survival of these patients depends largely on their physiological reserve, fast diagnosis and prompt medical or/and mainly used surgical treatment.

Review of the literature and clinical features of the pathology in question are also described and discussed.

Keywords: Ascending aortic graft infection; Large dimensions vegetation; Septic embolism; Superior mesenteric artery aneurysm; Hemorrhagic stroke

RESUMO

Os autores descrevem um caso clÃnico raro de uma embolia séptica para um membro inferior, um aneurisma micótico da artéria mesentérica superior e um acidente vascular cerebral hemorrágico causados por uma grande vegetação móvel em um enxerto protésico da aorta ascendente.

Enxertos protésicos infectados da aorta ascendente, devem ser tratados com um alto grau de suspeição, tendo sempre em mente que a sobrevida destes doentes depende largamente da sua cerebral hemorrágico reserva ï¬siológica, diagnóstico rápido e pronto tratamento médico e/ou mais frequentemente usado tratamento cirúrgico.

Uma revisão da literatura e das caracteristicas clÃnicas da patologia em questão são descritas e discutidas.

Palavras-chave: Infecção protésica da aorta ascendente; Vegetação de grandes dimensões; Embolia séptica; Aneurisma da artéria mesentérica superior; Acidente vascular cerebral hemorrágico

Introduction

Eradicating infections of ascending aortic graft remains a very demanding task that if not treated properly could lead to devastating consequences.

The authors present a clinical case of a large mobile vegetation in an ascending aortic graft that resulted in a septic embolism to a lower limb, a mycotic superior mesenteric artery aneurysm and a hemorrhagic stroke.

Case report

A 56-year-old male, former smoker, with arterial hypertension and an episode of acute myocardial infarction in 2004, was submitted to a cardio-thoracic surgery in the same year of the coronary event, in which a prosthetic aortic conduit (Dacron® graft) was inserted for correction of ascending aorta aneurysm.

After six years of surgery he initiated relapsing febrile episodes of unknown origin. The initial workup performed in other institutions in order to ï¬nd the fever outbreak was meticulous (Hemo and urine cultures, viral serology, tumor markers, abdominal ultrasound, CT thoraco-abdominopelvic, transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiogram, bone marrow cultures, bone scintigraphy, CT column, esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy), but inconclusive.

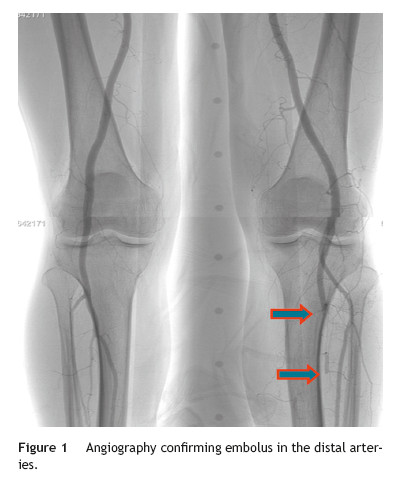

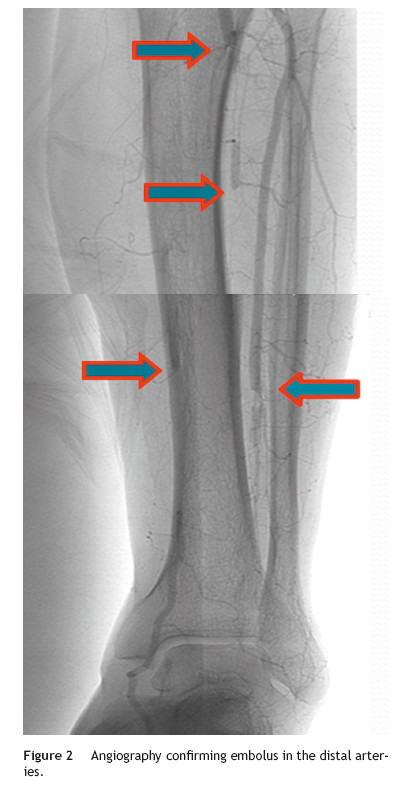

A few weeks later, the patient was brought to our hospital complaining of symptoms of acute left limb ischemia after a febrile peak (T-40 â¦C). At physical exam, the left limb presented with femoral and popliteal pulses, but distal pulses were absent, he had no loss of motor function. The contralateral limb had all pulses present. The ECG excluded cardiac arrhythmia. He had denied claudication history and after a popliteal aneurysm had been ruled out, an angiography was conducted and embolus in the three distal arteries was demonstrated (Figs. 1 and 2).

A mechanic thrombo-embolectomy was performed by infra-popliteal approach, with immediate relief of the ischemic complaints (ankle-braquial index of 0.75).

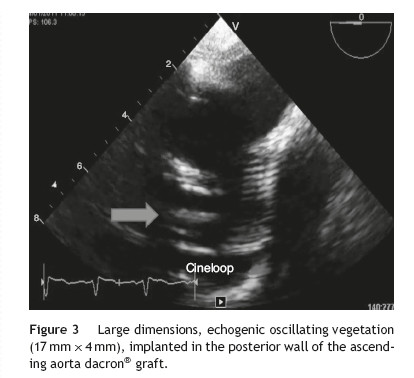

Because of persistent fever of unknown origin a trans-esophageal echocardiography was performed which revealed a large, echogenic, oscillating vegetation (17 mm à 4 mm) implanted in the posterior wall of the ascending aorta Dacron® graft, 27 mm above the aortic valve plane (Fig. 3).

Blood and thrombus cultures (collected during the hospitalization and surgery) were always negative.

The patient was then transferred to the hospital center where he performed the cardio-thoracic surgery in 2004 and there he completed 4 weeks of intravenous treatment with vancomycin and 6 weeks with gentamicin.

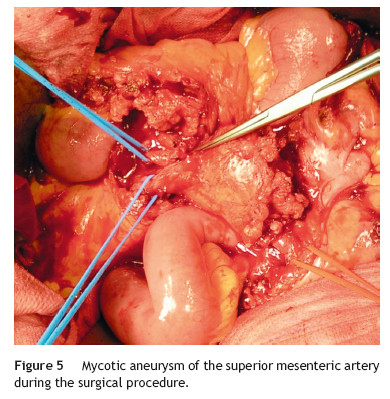

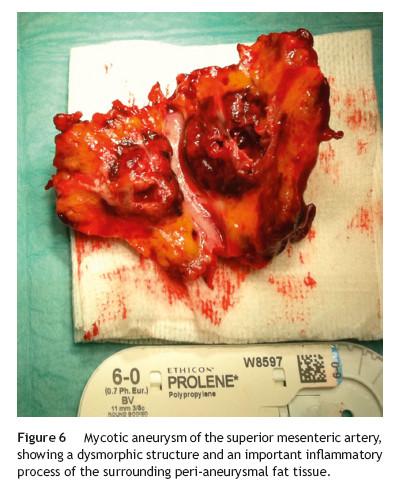

A month later, he is re-admitted to our emergency department with a persistent, diffused abdominal pain and a saccular superior mesenteric artery aneurysm of 34 mm, located 9 cm distally from the origin of this vessel, was detected in the computed tomography angiography (CTA) (Fig. 4). Surgery was conducted immediately by means of simple ligation to exclude the aneurysm (Figs. 5 and 6). A small portion of the small bowel became ischemic, and a segmental enterectomy was carried out without delay during the same procedure. After treatment of a small abdominal wound infection, he was discharged from our hospital. Once again there was no growth of blood or aneurysm bacterial cultures.

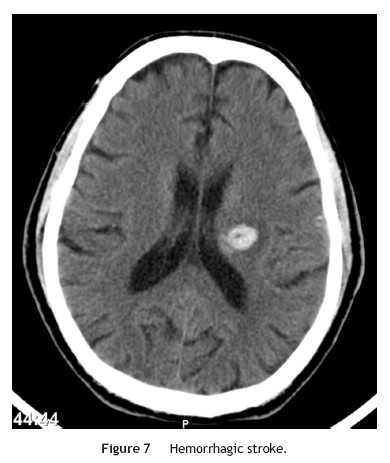

One month after discharge, he returned with a spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 7) (hemiparesis of the right upper limb, central facial paresis and dysarthria) and also a cellulites of the right upper limb.

After 3 months of intensive physiotherapy the patient recovered from his neurologic deï¬cits.

For the last 3 years the patient continues to be followed by us annually, has been working without limitations, with palpable distal pulses in both limbs and in an echocardiographic imaging recently performed a ââcleanââ prosthetic aortic conduit was demonstrated.

Discussion

Infection of an ascending aortic prosthesis is a serious complication, associated with a high mortality.

Because of their lethal potential, eradicating infections of ascending aortic grafts remains a very demanding task, especially when the infection extends into the aortic root (as in patients with composite valve grafts) or in the aortic arch.1

Although antibiotics represent an essential part of the treatment they are rarely effective alone.1 Some case reports in the literature describe a successful treatment with antibiotics alone2-5 but because of the great mortality induced by this approach, others however, state that this approach is not sufï¬cient, especially in cases of severe prosthetic infections.4

As for infected peripheral vascular grafts, reports recommend a combined medical and surgical treatment strategy that combines antibiotics, removal of all the prosthetic material, cleaning of the surrounding tissues, and extra-anatomic arterial reconstruction.6

However technically possible for the thoracic region,7 such a major surgical undertaking may not be suitable in the ascending aortic graft infections,1 mainly because of the technically challenging nature of the surgery and because most patients usually have multi-organ dysfunction caused by sepsis, making the procedure extremely risky.8

The most commonly micro-bacterial agents found are the Staphylococcus aureus and the Staphylococcus epidermidis.9

In 1984, Hargrove and Edmunds created the principles of the modern treatment of infected thoracic aortic grafts that continue to be used after so long. These guidelines include explanation and replacement of the infected material if suture lines are involved, extensive irrigation and tissue debridement, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and obliteration of dead space by autologous tissue.10

So, the two main questions that continue to cause controversy, are whether to remove the infected graft and if it is removed, what to replace it with.1

By now, the literature on the surgical treatment of ascending aortic graft infection fails to provide even the lowest level of evidence (level C, consensus expert opinion) in order to base a concrete recommendation.1

If an attentive to save the original graft is thought, what is especially important when we are facing a patient that could predict a poor outcome, because of the high morbi-mortality to remove and replace the graft, an extensive mediastinal debridement and irrigation is described with good results.11,12

Possible surgeries (predominantly before the era of bioprosthetic grafts) are graft removal and replacement with a synthetic graft, although leave prosthetic material in an infected ï¬eld makes it difï¬cult to eradicate the infection.1

Graft removal and replacement with a tissue graft (cryopreserved aortic homografts from cadaveric human aorta), that have the advantage to appear to be more resistant to infection than synthetic ones,13 are more ï¬exible,14 but have a predisposition to progressive deteriorate and need to be replaced.15

Porcine xenograft roots have also emerged as an alternative for aortic root infection.1

Choosing the right treatment time on which a systemic antibiotic should be maintained remains arbitrary, and the efï¬cacy and term of the treatment are doubtful.10 Scott A. LeMaire and colleagues recommend life-long antibiotic therapy, especially in patients with residual synthetic graft material.1

Hagl and colleagues recommend: if surgical cultures are positive, patients would receive at least 6 weeks of antibiotic treatment, if cultures are negative and organisms visualized in the Gram stain, antibiotics should be given by at least 4 weeks, and if both cultures and Gram stain are negative, antibiotic should be administered for only 2 weeks.15

Obviously, careful follow-up involving frequent imaging is required to detect any kind of further complications.

A cardiac infective endocarditis (IE) with constantly negative blood cultures are usually caused by intracellular bacteria as Coxiella burnetti, Bartonella, Chlamydia and recently demonstrated, Tropheryma Whipplei, the agent of the Whippleâs disease.16

In this disease, embolic events are a frequent and life-threatening complication of IE related to the migration of cardiac vegetations.

Embolic events may be totally silent in 20% of the patients with IE, especially those affecting the splenic or cerebral circulation (the most frequent sites of embolism).17

Factors associated with increased risk of embolism are the size and the mobility of the vegetations.17,18 The risk of new embolism peaks during the ï¬rst days following initiation of systemic antibiotic treatment and decreases during the following days, particularly beyond 14 days,19,20 although some risk always persists indeï¬nitely while vegetations remain present.

For this reason, the beneï¬ts of cardiac surgery to prevent embolism are greatest during the ï¬rst week of antibiotic therapy, when embolic risk is the highest.

The best means to reduce the risk of an embolic event is the prompt institution of appropriate antibiotic therapy.17

The overall beneï¬ts of surgery should be weighed against the operative risk and must consider the clinical status and co-morbidity of the patient.

Neurological events develop in 20-40% of the patients with IE and are mainly the consequence of cardiac vegetation embolism.21,22

The clinical spectrum of these complications is wide, as naturally expected they are associated with an excess mortality, particularly in the case of stroke.23 So, rapid diagnosis and initiation of appropriate antibiotics are of major importance to prevent a ï¬rst or recurrent neurological complication.

Conversely, in cases with intracranial hemorrhage, neurological prognosis is worse and surgery must be postponed for at least 1 month.24

The Superior Mesenteric Artery Aneurysms (SMAA) represents 5.5% of all splanchnic artery aneurysms and appears to have no differences between genders.25 Mycotic aneurysms account for 60% of all SMAA cases and are thought to commonly occur as a result of subacute bacterial endocarditis with infection by nonhemolytic Streptococcus. 25-27

The majority (70-90%) of SMAA are symptomatic at the initial evaluation.25

It is thought that rupture usually occurs in as many as 50% of the patients26 and is associated with a mortality rate around 30-90%.25

Treatment of SMAA should be conducted regardless of size or symptomatology because of the high mortality risk associated with the potential rupture.27

When surgical therapy is considered, some SMAA can be ligated and excised safely because of the extensive collateral ï¬ow to the bowel via the celiac artery and the inferior mesenteric artery.27

Conclusions

Despite the apparent reported good results for the complications held by the vascular surgeons from our hospital and after performing a literature review, we think it was a bad judgment on the treatment of an ascending aortic graft infection, that even after antibiotherapy to eradicate a large vegetation, caused several life-threatening vascular complications. That could be handled with immediate thoracic surgery in order to prevent these described pathological occurrences.

The surgeries typically described to solve this kind of complication are: graft removal and replacement with a synthetic graft or tissue graft (cryopreserved aortic homograft) and extensive mediastinal debridement and irrigation with use or not of viable tissue (pedicle omental or muscle ï¬ap) to cover the dead space.

Although antibiotics represent an essential part of the treatment of this entity and because of the great mortality induced by this approach, several authors emphasize that antibiotics alone are not sufï¬cient to treat, especially in severe prosthetic infections.4

By now, the literature on the surgical treatment of ascending aortic graft infection fails to provide even the lowest level of evidence (level C, consensus expert opinion) on which to base a concrete recommendation on the best possible treatment.1

Infected ascending aortic grafts should be handled with high level of suspicion, always bearing in mind that the survival of these patients depends largely on their physiological reserve, fast diagnosis and prompt medical or/and mainly used surgical treatment.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Conï¬dentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conï¬icts of interest

The authors have no conï¬icts of interest to declare.

References

1. LeMaire SA, Coselli JS. Options for managing infected ascending aortic grafts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(4): 839-43. [ Links ]

2. Coselli JS, Crawford ES, Williams TW Jr, et al. Treatment of postoperative infection of ascending aorta and transverse aortic arch, including use of viable omentum and muscle ï¬aps. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;50:868-81. [ Links ]

3. Coselli JS, Köksoy C, LeMaire SA. Management of thoracic aortic graft infections. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1990-3. [ Links ]

4. Gott VL, Cameron DE, Alejo DE, et al. Aortic root replacement in 271 Marfan patients: a 24-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:438-43. [ Links ]

5. Gott VL, Gillinov AM, Pyeritz RE, et al. Aortic root replacement: risk factor analysis of a seventeenyear experience with 270 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;109:536-44. [ Links ]

6. Soyer R, Bessou JP, Bouchart F. Surgical treatment of infected composite graft after replacement of ascending aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:425-8. [ Links ]

7. Bove EL, Parker FB Jr, Marvasti MA. Complete extraanatomic bypass of the aortic root: treatment of recurrent mediastinal infection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;86:932-4. [ Links ]

8. Akowuah E, Narayan P, Angelini G, et al. Management of prosthetic graft infection after surgery of the thoracic aorta: Removal of the prosthetic graft is not necessary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(4):1051-2. [ Links ]

9. Sharp WJ, Hobballah JJ, Mohan CR. The management of the infected aortic prosthesis: a current decade of experience. J Vasc Surg. 1994;16:844. [ Links ]

10. Hargrove WC 3rd, Edmunds LH Jr. Manegement of infected thoracic aortic prosthetic grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 1984;37:72. [ Links ]

11. LeMaire SA, DiBardino DJ, Köksoy C, et al. Proximal aortic reoperations in patients with composite valve grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:S1777-80. [ Links ]

12. Nakajima N, Masuda M, Ichinose M, et al. A new method for the treatment of graft infection in the thoracic aorta: in situ preservation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1994-6. [ Links ]

13. Vogt PR, Brunner-LaRocca HP, Lachat M. Technical details with the use of cryopreserved arterial allografts for aortic infection: inï¬uence on early and midterm mortality. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:80-6. [ Links ]

14. Lytle BW, Sabik JF, Blackstone EH. Reoperative cryopreserved root and ascending aorta replacement for acute aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:S1754-7. [ Links ]

15. Hagl C, Galla JD, Lansman SL, et al. Replacing the ascending aorta and aortic valve for acute prosthetic valve endocarditis: is using prosthetic material contraindicated? Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:S1781-5. [ Links ]

16. Richardson DC, Burrows LL, Korithoski B. Tropheryma whippelii as a cause of afebrile culture-negative endocarditis: the evolving spectrum of Whippleâs disease. J Infect. 2003;47:170-3. [ Links ]

17. Di Salvo G, Habib G, Pergola V. Echocardiography predicts embolic events in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1069-76. [ Links ]

18. Thuny F, Di Salvo G, Belliard O. Risk of embolism and death in infective endocarditis: prognostic value of echocardiography: a prospective multicenter study. Circulation. 2005;112:69-75. [ Links ]

19. Steckelberg JM, Murphy JG, Ballard D. Emboli in infective endocarditis: the prognostic value of echocardiography. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:635-40. [ Links ]

20. Dickerman SA, Abrutyn E, Barsic B. The relationship between the initiation of antimicrobial therapy and the incidence of stroke in infective endocarditis: an analysis from the ICE Prospective Cohort Study (ICE-PCS). Am Heart J. 2007;154: 1086-94. [ Links ]

21. Heiro M, Nikoskelainen J, Engblom E, et al. Neurologic manifestations of infective endocarditis: a 17-year experience in a teaching hospital in Finland. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2781-7. [ Links ]

22. Anderson DJ, Goldstein LB, Wilkinson WE, et al. Stroke location, characterization, severity, and outcome in mitral vs aortic valve endocarditis. Neurology. 2003;61:1341-6. [ Links ]

23. Hasbun R, Vikram HR, Barakat LA. Complicated left-sided native valve endocarditis in adults: risk classiï¬cation for mortality. JAMA. 2003;289:1933-40. [ Links ]

24. Eishi K, Kawazoe K, Kuriyama Y. Surgical management of infective endocarditis associated with cerebral complications. Multicenter retrospective study in Japan. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:1745-55. [ Links ]

25. Lorelli DR, Cambria RA, Seabrook GR, et al. Diagnosis and management of aneurysms involving the superior mesenteric artery and its branches-a report of four cases. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;37:59-66. [ Links ]

26. Stone WM, Abbas M, Cherry KJ, et al. Superior mesenteric artery aneurysms: is presence an indication for intervention? J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:234-7. [ Links ]

27. Rockman CB, Maldonado TS. Chapter 138: splanchnic artery aneurysm. Rutherfordâs vascular surgery, 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2010. p. 2141-55. [ Links ]

E-mail address: joselopes1983@sapo.pt (J. Almeida-Lopes).

Received 31 October 2014;

Accepted 8 December 2014

Available online 10 January 2015

Notes

* Presented in form of oral communication in the 36th Charing Cross Symposium, EVST Session. London, 8th April 2014.