Introduction

Acute limb ischemia (ALI) is one of the most common causes of urgent vascular interventions.(1) Despite all the improvements in revascularization techniques and postoperative care, ALI outcomes remain poor with limb loss and mortality rates of 12-50% and 20-40% at one year, respectively.(1-7) ALI management in the emergency setting is complex. Decision-making relies on the Rutherford classification for ALI, a categorical scale prone to interobserver subjective interpretations.

In many areas of Medicine, biomarkers have been proving their role in disease diagnosis, in the monitorization of pathological activity and in the development of outcome prediction models. Also, in Vascular Surgery, increasing interest is held towards biomarkers that can empower previously established risk-models making them more accurate - see the example of the ERICVA model.(8) Complex inflammatory interactions occur ubiquitously in the vascular bed during acute/subacute ischemic events, having an important role in ALI pathological pathway.(9) In recent years, much attention has been held towards the prognostic value that simple, widely available and low cost preoperative inflammatory biomarkers might have.(10) More important than individual biomarkers, the relationship between hematological cell types may hold even more reliable information. For example, the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) are easily calculated from basic admission hemogram, do not require any additional analysis and have been proving their prognostic ability in Oncological and Cardiovascular pathologies.(11-15) Nevertheless, the inclusion of these biomarkers in ALI decision-making remain debatable due to the scarce literature evidence.(2)

The aim of this review was to identify studies that support the value of preoperative inflammatory biomarkers, specifically the NLR and the PLR, for outcome prediction after revascularization for ALI.

Material and methods

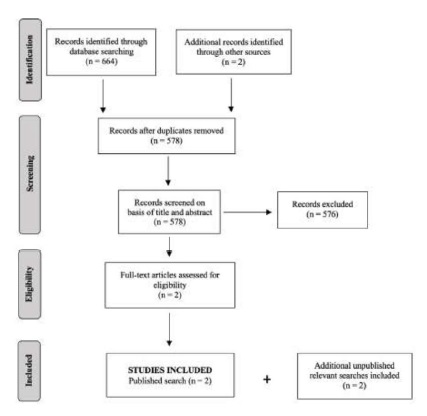

The objectives of this systematic review, criteria for study inclusion and methods of analysis were pre-specified in a protocol. This review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines.(16)

Eligibility criteria

The authors attempted to identify all the cohort studies that investigated and compared preoperative inflammatory biomarkers, specifically the NLR and the PLR, with the outcomes in patients submitted to revascularization for ALI. Reviews were excluded.

Literature search methods

A comprehensive and systematic search of the literature according to PRISMA guidelines was undertaken for relevant studies. This search was applied to Medline (1992-present). The last search run was in August 2020. Reference lists from retrieved reports were scrutinized for additional potentially eligible articles. Only English language articles were considered. The following Medical subject headings and other keywords were used to identify relevant articles: ((((((acute limb ischemia) OR (acute arterial occlusion)) OR (arterial occlusive diseases)) OR (limb ischemia)) AND ((((((((inflammation mediators) OR (neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio)) OR (platelet-lymphocyte ratio)) OR (lymphocyte count)) OR (neutrophils)) OR (mean platelet volume)) OR (platelet count)) OR (inflammatory parameters))) AND (((((((((((((prognosis) OR (prognostic biomarker)) OR (predictor)) OR (morbidity)) OR (mortality)) OR (amputation)) OR (amputation-free survival)) OR (adverse effects)) OR (limb salvage)) OR (risk factors)) OR (treatment outcome)) OR (embolectomy adverse effects)) OR (embolectomy mortality))) AND ("Treatment Outcome"[Mesh]).

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility for study inclusion was conducted by the lead author (N.H.C.). The information entered detailed: study characteristics, including publication date, recruitment period, inclusion and exclusion criteria, total number of patients, type of intervention, follow-up and outcome (mainly limb loss and mortality).

Results

Literature search results and description of studies

The search of Medline database provided a total of 664 citations. Two additional records were identified through other sources. After adjustment for duplicates, 578 remained and were screened. Of these, 576 studies were discarded because these papers did not meet the inclusion criteria after reviewing their abstracts. The full text of the remaining two published citations was screened and they were included in the systematic review. Two unpublished relevant researches were obtained and included: one research letter from Spain and one unpublished paper from the same authors of this systematic review. The literature search strategy is provided in Figure 1.

Synthesis of results and outcome

The selected four studies for this review were retrospective observational cohorts. Inclusion criteria were similar between studies with that being consecutive patients attending for an ALI episode in a Tertiary Hospital. Follow-up periods were reported in all of them. Three of them (Taolu, et al(17,) Carmona, et al(19) and Coelho, et al) focused not only in the perioperative period but also in long-term follow-up, while Saskin, et al(18) analyzed only 30-day outcomes. In all studies, the primary outcome was amputation and survival. All studies reported clinical characteristics, risk factors, preoperative laboratory data, treatment modalities and intervention outcomes.

Taolu, et al(17) examined the predictive ability of admission NLR for predicting amputation in ALI patients submitted to embolectomy. 254 individuals with a mean age of 66.04 ± 13.30 years were followed over 26 months. Intervention was embolectomy in 92% cases and infra-inguinal bypass in 8% patients. In a multivariate logistic regression model, no arterial back bleeding during intervention and higher preoperative NLR were found to be independent risk factors for amputation within 30 days or during follow-up. Through a receiver operating curve (ROC), NLR e 5.2 was found to have an 83% sensitivity and 63% specificity for predicting amputation within 30 days in this population (area under curve (AUC) of 0.8).

Saskin, et al(18) analyzed 123 patients submitted to thromboembolectomy for ALI and compared the preoperative clinical and hematological parameters of patients in whom no perioperative amputation was performed (n = 91) in opposition to those who suffered amputation within 30 days after the intervention (n = 32). They found that those who suffered lower limb amputation presented with higher preoperative RDW, MPV, NLR, PLR and C-reactive protein. They concluded that such markers of inflammation can predict amputation in acute arterial thromboembolism patients.

In a research letter published online in March 2020 at the European Journal of Vascular et Endovascular Surgery, Carmona et al(19) report a cohort of 265 patients admitted due to ALI secondary to native artery occlusion. Survival rate demonstrated to have a significant linear association with NLR in the spline analysis. After adjustment, NLR was found to be an independent risk factor for lower survival rates (for each unit increase in NLR the odds ratio (OR) was 1.025, 95%CI, 1.002-1.048). No significant association between NLR and limb salvage was found.

In a recent retrospective cohort study (yet unpublished) encompassing 345 patients requiring urgent revascularization for ALI Rutherford grade IIa or IIb we found that NLR was an independently associated with perioperative (30-day) amputation or death (OR 1.28, 95%CI [1.12-1.47], p < .001). ROC curve explored the relationship between preoperative NLR and 30-day death or major amputation. An optimized cutoff value NLR e 5.4 demonstrated to have a 90.5% sensitivity and 73.6% specificity for predicting 30-day death or amputation (AUC 0.86).

Discussion

As this systematic review shows, there are in fact few studies that analyze the predictive ability of preoperative inflammatory biomarkers in ALI. Nevertheless, these four cohort studies demonstrate that inflammatory biomarkers might have a role in ALI preoperative risk stratification.

Inflammation is an early key feature during the ischemic insult and several related immune-inflammatory pathways occur simultaneously. They are translated into morphologic and numeric changes in several cell lines.(20) Red blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes and platelets are involved in the pathologic ischemic pathway. Neutrophilia is associated with the acute inflammatory response to tissue ischemic injury, atherosclerotic plaque disruption and hypercoagulable state both of which are hallmarks of ALI.(21) Platelets also play a key role by enhancing platelet-mediated thrombus formation.(10,12) On the other hand, the ischemic event leads to physiologic stress associated with cortisol and catecholamine release which is responsible for lymphocytes count reduction and functionality.(20,22) As a consequence, a simple blood can hold much information regarding ischemic process. The relationship between inflammation mediators and treatment outcome is already in wide application in the oncology and cardiology. The interest about inflammatory biomarkers’ prognostic capacity is currently a trending topic with more than 50.000 citations in PubMed, only in the last decade. Additionally, increasing evidence points out that these ratios can also have an important prognostic role in vascular diseases such as acute aortic dissection(23,) abdominal aortic aneurysm(24,25), cerebrovascular disease(26,) critical limb ischemia(8) and venous thromboembolism(27).

It is virtually impossible to create a universal management and treatment algorithm for ALI considering its heterogeneity in etiology, clinical presentation and severity. Decision-making regarding timing and type of intervention is challenging and relies mostly upon the Rutherford classification for ALI.(2,28) However, assessment of its categorical components (such as sensory loss or motor deficit) are prone to interobserver variation.(28) Being a continuous numerical ratios, biomarkers like NLR or PLR potentially stands as a simple, widely available and inexpensive biomarkers that can add the required objectivity to ALI patient evaluation. The combination of their objectivity with the Rutherford categorical information could effectively empower its risk-stratification ability. Recent European Society for Vascular Surgery ALI Guidelines point out that “there are no studies that support the routine use of biomarkers to predict limb salvage and survival after ALI”. The Writing Committee gave a IIIC recommendation to myoglobin and creatinine kinase use to base the decision to offer revascularization or primary amputation.(2) These are however late ischemic markers showcasing muscle damage. On the other hand, inflammatory biomarkers like NLR or PLR could potentially reflect an early systemic response to ALI. As seen in Taolu, et al(17) and in our recent study, preprocedural NLR had a high discriminative power (AUC of 0.80 and 0.86, respectively) and could effectively impact preintervention risk-stratification. Based on these two studies, when evaluating a patient with ALI with an elevated NLR (e 5.2 in Taolu et al and e 5.4 in our study) one should be aware of a probably adverse prognosis.

Risk of possible confounders for biomarkers analysis like a concomitant active infection, active cancer, hematopoietic system disorders, recent anti-inflammatory medication and/or recent cardio or cerebrovascular event should be considered and explain the low specificity reported in all studies. Nevertheless, the high sensitivity (around 90%) suggests that these ratios can effectively recognize which patients are at higher risk for perioperative death or amputation and thus require emergent treatment and additional postoperative support.

The results of the present review need to be interpreted in the context of limitations. The main limitation is that all the analyzed reports are single-centre observational cohort studies and it is difficult (if not impossible) to definitely exclude selection bias to some extent. Different ALI etiologies (cardioembolic, in situ, secondary thrombosis…), as well as heterogeneous treatment options (thromboembolectomy, bypass…), were included and thus might had also influenced the outcome. However, by including the full breadth of patients and treatments, these studies reflect real-word data from usual clinical practice, translating the potential application of these biomarkers in everyday practice. Even though a rigorous search strategy was applied to identify relevant reports, some studies may have escaped consideration.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that although limited literature exists, inflammatory biomarkers, such as NLR and PLR, might have a role in preoperative risk stratification in ALI. In the future, the definition of levels and trends of inflammatory biomarkers and their relationship with treatment outcome could be the key to further increase their clinical usefulness. Both timing and treatment selection could be better defined, leading to potential improvements in ALI morbimortality. Prospective multicentric validation studies are needed.