Introduction

Occlusive ilio-femoral disease may limit endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) by jeopardizing endograft implantation and patency. These patients may present with concomitant chronic limb threatening ischemia (CLTI) and often have significant comorbidities precluding open interventions. Traditionally, endovascular treatment of these patients consisted in aortouniiliac devices combined with femoro-femoral bypass (AIU-FFB), condemning important collateral pathways. With the combination of hybrid techniques, lower-profile and flexible hydrophilic devices (allowing easier passage through difficult anatomy), standard bifurcated endografts may be a feasible and durable option. We present a challenging case of a 68-year-old man with concomitant bilateral common iliac aneurysms and severe ilio-femoral occlusive disease.

Case report

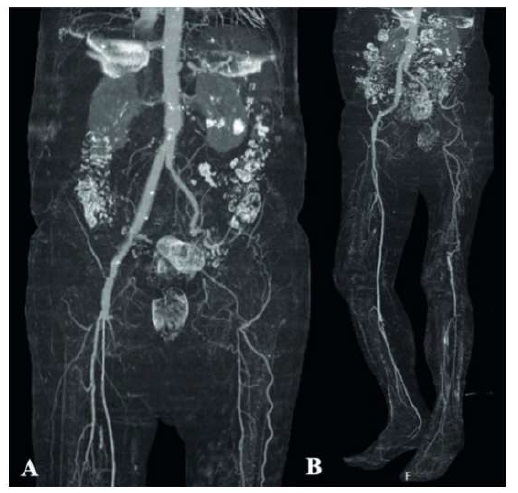

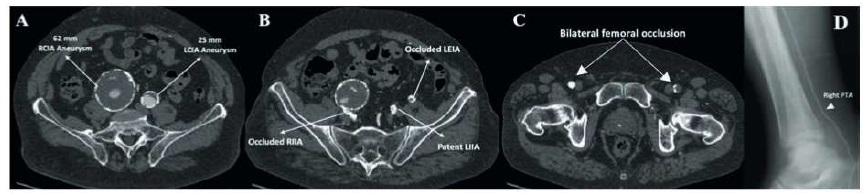

A 68-year-old male patient was referred to our outpatient clinic due to right lower limb CLTI. His medical history was positive for tobacco use, overweight, diabetes, hypertension, COPD (GOLD 3) and coronary artery disease (stable angina). Peripheral vascular examination revealed absence of both femoral pulses and presenting an ankle-brachial index (ABI) of 0.14 and 0.42 at right and left, respectively. He presented a right 4th toe gangrene and a 4×4 cm lateral malleolus infected ulcer, with bone exposure, that resulted from the position he adopted for pain relief (WIfI classification: 3 3 2)(1). He was asymptomatic at the left side. A computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed bilateral common iliac aneurysms (62 mm at right and 25 mm at left) combined with severe ilio-femoral occlusive disease (Figure 1). On the right side, the internal iliac artery (RIIA) was occluded. Although patent, the external iliac artery (REIA) had a significant stenosed and tortuous proximal portion due to aneurysm induced deformation, translating in low amplitude monophasic doppler waveforms in distal REIA. On the left side, the internal iliac artery (LIIA) remained patent, with complete external iliac artery (LEIA) occlusion. Common femoral, superficial femoral and popliteal arteries were bilaterally occluded. On the right side, a patent posterior tibial artery was a potential target for a femoro-distal bypass.

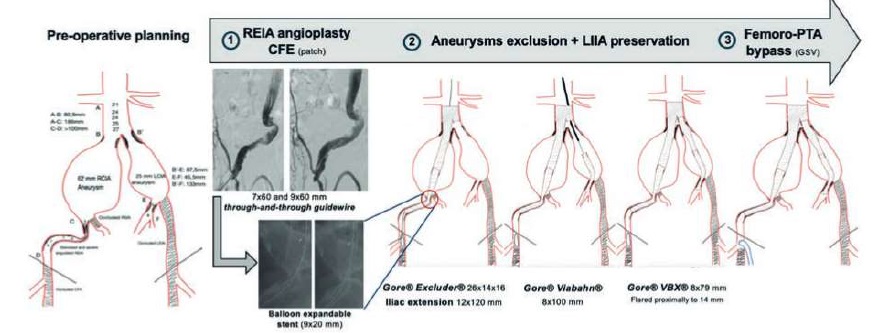

Considering patient's prohibitive surgical risk for an open abdominal surgery or general anesthesia, we decided to attempt a three-staged hybrid procedure, detailed in Figure 2, under local/regional anesthesia.

First, we performed REIA angioplasty (7×60 and 9×60 mm, with a through-and-through wire - 5F left brachial sheath and 4F femoral introducer) and a right femoral endarterectomy with patch (Dacron) angioplasty. For infection control, we also did a 4th toe guillotine amputation and ulcer debridement.

Figure 1 Preoperative CTA. A: Right (62 mm) and left (25 mm) common iliac aneurysms. B: Occluded RIIA, with patent LIIA. C: Bilateral common femoral occlusion. D: Patent right posterior tibial artery. RCIA: right common iliac artery; LCIA: left common iliac artery; RIIA: right internal iliac artery; LIIA: left internal iliac artery; LEIA: left external iliac artery; PTA: posterior tibial artery

Figure 2 Pre-operative planning and detailed three-staged hybrid procedure. Full description on the text. RCIA: right common iliac artery; LCIA: left common iliac artery; REIA: right external iliac artery; CFE: common femoral endarterectomy; LIIA: left internal iliac artery; PTA: posterior tibial artery; GSV: great saphenous vein

Three weeks later, we excluded the RCIA aneurysm with a bifurcated device (Excluder 261416, W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) associated with ipsilateral iliac extension (PLC 121200, W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), landing at EIA (right retrograde percutaneous femoral access, 18Fr introducer). From a left retrograde brachial access (8F sheath - Flexor KCFW, Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana) we catheterize the LIIA and deployed a 8×100 mm self-expandable covered stent (Viabahn®, W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) with stent-bridging to the contralateral gate of the bifurcated device with a 8×79 mm covered balloon-expandable stent (VBX®, W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), flared proximally at 14 mm. Completion angiography revealed a significant right iliac limb kinking (on the same proximal REIA portion previously dilatated) and a 9×39 mm balloon-expandable bare metal stent (Omnilink®, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA) was implanted with complete resolution.

Finally, 3 weeks later, we did a right femoro-posterior tibial artery bypass (reversed ipsilateral GSV), obtaining posterior tibial pulse at the end of surgery.

At 1,5 years follow-up, patient is asymptomatic, presenting healed 4th toe amputation and a practically healed lateral malleolus ulcer (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Pre- (A and C) and post-intervention (B and D) evolution of the lateral malleolus ulcer and 4th toe gangrene

Follow-up CTA showed correct endograft positioning, aneurysm sac reduction, no endoleaks and a patent LIIA (Figure 4).

Discussion

Simultaneous occurrence of aneurysmal and occlusive aorto-iliac disease is not uncommon (ranging between 10 to 40% patients)(2). Besides hostile proximal neck anatomy, inadequate access vessels represent the second most common cause to set aside an EVAR, in up to 6 to 15,4% patients(3,4). These patients often have severe comorbidities and may not be good candidates for open repair. Hybrid strategies as using iliac conduits or an AUI-FFB are the most common treatment options. However, the retroperitoneal incision required for the conduit can be associated with wound complications demanding longer hospital stay(2). On the other side, AUI-FFB have decreased patency (≈ 60% at 3 years) in aorto-iliac occlusive disease patients, have a higher risk for steal and cause the loss of some important collateral pathways(2,5,6). Considering patient poor medical condition, an open abdominal intervention or a general anesthesia were set aside. We decided to begin with REIA angioplasty and femoral endarterectomy to establish an arterial access for the subsequent aneurysm repair. After through-and-through wire passage and iliac angioplasty we were able to obtain a pulsatile inflow that allowed us to perform the common femoral endarterectomy. In the second stage, besides iliac aneurysms exclusion, LIIA preservation was of paramount importance not only to secure the pelvic flow (RIIA was occluded), but also to maintain left lower limb perfusion through LIIA collateralization. Left external iliac and common femoral arteries recanalization and implantation of a side-branched graft or a sandwich technique could also have been alternatives. However, since the patient was asymptomatic on that side, we thought that these extra-steps could not only lead to LIIA inadvertent occlusion and but would also add time and complexity the procedure without clinical benefit. We chose an Excluder endograft (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) because of its lower profile and flexibility and also because its limbs are associated with a lower occlusion rate due to limb kinking in challenging iliac anatomies(7,8). Considering LIIA diameter (initial portion with 5-6 mm diameter) and tortuosity and because we were coming from a retrograde brachial access, we decided to use a Viabahn (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA). Bridging stent to the bifurcated endograft was achieved with a VBX (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), taking advantage of its independent stainless-steel rings that allowed a tailorable proximal diameter of 14 mm, perfectly adjusted to the contralateral gate. Regarding this particular matter, one should anticipate the shortening of the stent to use all the sealing length on the contralateral gate. Compared to a lengthy all-in-one procedure, the reported three-staged intervention allowed an excellent patient tolerability and cooperation during each intervention, even under local/regional anesthesia. We also felt that enable the patient to recover at home between each procedure was important, reducing the overall hospital stay.

Conclusion

Complex aorto-iliac aneurysmal and occlusive disease can pose difficult challenges, especially in patients with poor medical condition. The detailed planning, the combination of surgical and endovascular techniques and the steps described in this report proved feasible and were associated with durable midterm patency and excellent clinical outcome.