Introduction

Traditionally, the treatment of ALI requires an open surgical intervention, and is associated with relatively high perioperative morbidity and mortality1. In recent decades, the use of catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) to treat ALI has become part of routine clinical care, primarily due to three large randomised controlled trials that demonstrated similar efficacies, when compared with open surgery2-4.

The CDT was introduced at our institution in 2011. The change in protocol occurred due to the discouraging results of surgical thrombectomy obtained in the same institution and published by the same author with a primary permeability at one year of 17.9% (PE = 6.5%), limb salvage rate at 1 month of 56.6% (PE = 6.9%) and at 4.5 years 40.3% (PE = 7.1)5.

Importantly, CDT facilitated the treatment of increased patient numbers, thus it was broadened to other aetiologies. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to present CDT data from our institute, in ALI for different aetiologies. We present these data using primary patency, amputation rate, complications and death as primary outcomes.

Material and methods

Data Collection

This was a retrospective single centre analysis of electronic clinical data from consecutive patients with lower ALI, treated with CDT. All patients with acute occlusions below the abdominal aorta, undergoing thrombolysis between January 2011 and August 2017 were included.

The CDT protocol

Preferential arterial access was via the common femoral artery. If not available, a brachial puncture was performed. A sheath was placed anterograde or retrograde with low dose heparin infusion (500 U/h), and an intrathrombus straight catheter with multiple side holes, with a bolus of 1 mg alteplase and perfusion at a fixed dose of 0.5 mg/h. After procedure patients were admitted to an intermediate care unit under non-invasive monitoring. They had a daily angiography evaluation, with catheter adjustment based on angiographic findings, until technique success/failure was established, or interrupted due to complications.

Statistics

Data were analysed with IBM® SPSS Statistic, version 25. Univariate analyses of binary nominal and ordinal variables were conducted using cross-tabulations.

T-tests for independent continuous variables and the Kaplan-Meier method were used to estimate primary permeability, mortality and death rates. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Study definitions

ALI was defined as relatively recent (< 15 days) onset or worsening of ischaemic manifestations of the lower extremities, divided by Rutherford classification (I, IIa, IIb and III).

Complications due to CDT included minor bleeding, defined as haematoma and bleeding from the access site. Major bleeding was defined where surgical intervention was required, i.e. gastrointestinal bleeding, cerebral haemorrhage or the blood transfusion of more than two units.

Adjuvant revascularisation was defined by the requirement for an additional procedure (endovascular or surgical) during the same hospital stay, when CDT was technically success. Success was defined as CDT that results in vessel patency, regardless of the need for adjuvant revascularisation.

Primary patency was defined as a vessel or graft that remained patent after the initial procedure (with or without adjuvant revascularisation), and no additional intervention. Re-intervention was defined as occlusion in the same arterial segment that was previously thrombolysed. Major amputation was defined as amputation above the ankle joint.

Results

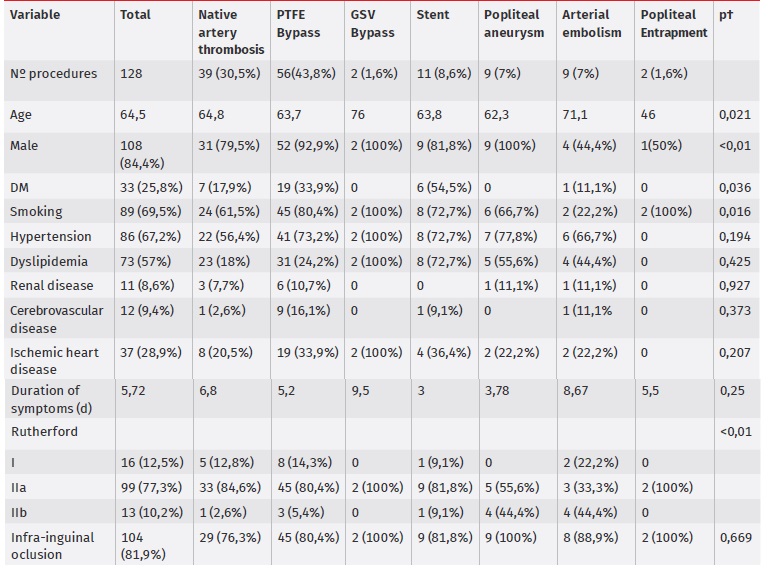

Between January 2011 and August 2017, 128 limbs were treated for ALI in 106 patients. Baseline demographics and comorbidities are shown (Table 1). The median follow-up time was 14 months [range: 6-31 months]. The mean age was 64.5 years [95% CI: 57-74], with mostly men (n = 108, 84.4%, p < 0.01) participating. Ischaemia aetiology include native artery thrombosis in 39 procedures (30.5%), PTFE graft thrombosis in 56 (43.8%), intra-stent thrombosis in 11 (8.6%), arterial embolism in nine (7%), popliteal aneurysm thrombosis in nine (7%), vein graft thrombosis in two (1.6%), and popliteal artery entrapment in two (1.6%). At presentation, 12.5% of patients had a viable extremity (Rutherford class I), 77.3% suffered a marginally threatened extremity (class IIa), 10.2% had an immediately threatening extremity (class IIb), and no patients showed irreversible ischaemia (class III). Adjuvant endovascular or open surgical procedures were common after thrombolysis (53.9%), with differences observed between all groups (p < 0.01). All adjuvant procedures in the popliteal aneurysm group were performed by open surgery.

Table 1 Baseline demographics and characteristics

p < 0.050 versus other groups.

† Comparisons of all groups (cross tabulation with chi-square test for dichotomous variables and one way ANOVA for continuous variables).

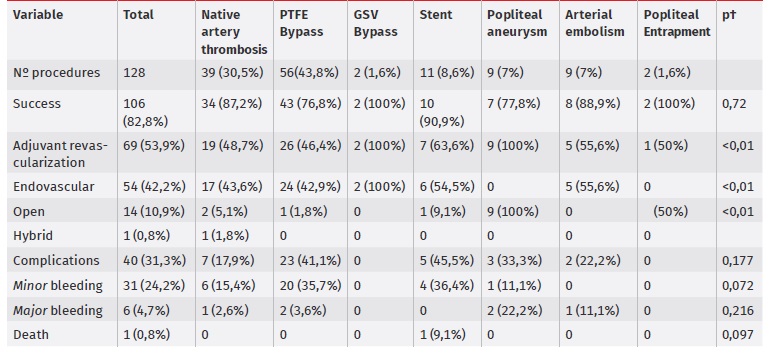

Table 2 CDT outcomes

p < 0.050 versus other groups.

† Comparisons of all groups (cross tabulation with chi-square test for dichotomous variables and one way ANOVA for continuous variables).

Technical success was recorded in 106 procedures (82.8%), with no differences between groups. Complications occurred in 40 procedures (31.3%), in most cases due to minor bleeding (n = 31), but some cases were due to major bleeding (n = 6), and one death was recorded due to haemorrhagic stroke. The need to interrupt CDT due to haemorrhagic complication occurred in 17 procedures.

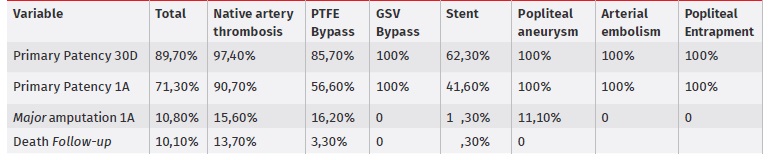

Primary outcomes are shown (Table 2). The overall primary patency rates were 89.7% and 71.3% at one month and one year, respectively, during which the stent group showed the poorest results: 47% at one year; whereas the popliteal aneurysm, arterial embolism and popliteal entrapment groups had no recorded occlusions. The need for re-intervention when required, was performed in 27.6% in the native artery thrombosis group, 65.2% in the PTFE graft thrombosis group, and 18.2% in the intra-stent thrombosis group. No re-interventions were verified for popliteal aneurysm or arterial embolism aetiologies.

Major amputations at one year occurred in 18 cases, with no differences between groups. No amputations were recorded in the great saphenous vein bypass, popliteal aneurysm, arterial embolism and entrapment popliteal groups.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in our institution, the treatment of ALI by CDT introduced a paradigm shift, and improved prognosis in these patients, when compared with previous institution data5. The study also presented an opportunity to investigate short and medium-term results for different subgroups, depending on the underlying cause of ALI. Our improvements were reflected by primary patency rates, amputation rates and number of deaths.

The primary success was 82.8%, similar to previous studies6-8, and the poorest results were observed in the PTFE bypass group, with a success rate of 76.8%.

The overall primary patency rates at one month and one year were 89.7% and 71.3%, respectively, with the poorest results in the stent group (62.3% and 41.6% at one month and one year, respectively). This observation may result from progression disease with no adjuvant revascularisation in remaining residual lesions in the end of CDT.

A known and accepted disadvantage of thrombolysis is the increased risk of haemorrhagic complications9,10. In this study, our complication numbers were similar to previous studies11,12, with an overall incidence rate of 31%. However, most reported bleeding was minor (24.2%), with a major bleeding incidence rate observed in only 4.7% of procedures. One death was recorded for haemorrhagic stroke (0.8%). These results corresponded to a lower incidence of serious bleeding complications, when compared to previous studies13,14. This low rate may be explained by strict patient surveillance in intermediate care units, and an immediate cessation or dose decrease in thrombolytic when bleeding was observed. Our rate of amputation at one year was 10.8%, similar to a previous study15.

Our study had some limitations. Firstly, it was retrospective in nature, and therefore had all the limitations associated with this study design. However, in mitigation, it included all consecutive cases in the study period. Secondly, the distinction between thrombotic and embolic occlusion, based on imaging findings are sometimes difficult, which may have led to imprecise classification. Nevertheless for all doubtful cases, two or more opinions were required to agree on aetiology.