Introduction

Inferior vena cava (IVC) formation is a complex process that occurs during embryogenesis (6-8 weeks of gestation) by development, regression, and anastomosis of three sets of paired veins:

the posterior cardinal, subcardinal, and supracardinal veins. Usually, the IVC is then converted to a unilateral right-sided system consisting of the infra-renal, renal, supra-renal and hepatic segments1.

Inferior vena cava agenesis (IVCA) is one of the most uncommon anomalies of this vessel, with an estimated prevalence of 0.0005-1% in the general population2. IVCA can be congenital, occurring in utero due to abnormal formation of the paired veins or prenatal thrombosis, or it can occur due to a postnatal thrombosis in early life3,4.

IVCA may be found as two different variants, complete or segmental agenesis3. The most common agenesis is the suprarenal segment, while agenesis of the hepatic and infrarenal segment constitutes only 6% of all cases2.

Congenital risk factors are rare as cause of DVTs, but IVCA is emerging as a significant risk factor that may contribute to DVT in healthy, young adults5.

Around 5% of the patients younger than 30 years with a diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) have an IVCA2 and so in young patients with idiopathic deep venous thrombosis, an inferior vena cava anomaly should be considered6. Physical exertion has been identified as a risk factor for DVT in patients with IVCA and as a precipitating event of the clinical presentation7, because the collaterals developed before DVT are unable to assure the increased blood flow due to major physical exertion, thereby generating venous stasis and clotting4.

Methods and material

Report of two clinical cases of vena cava agenesis with different clinical presentations.

Clinical case 1

A 40-year-old man was admitted with a 3 days history of unilateral lower limb swelling and pain, gradually progressing to the inability to walk. The patient had never had these symptoms before and had no family history of thrombosis. On questioning he referred

a history of extreme physical activity the previous days. He had a negative medical or surgical history and was not taking any medication. On physical examination, was found swelling, bruising and tenderness involving leg and thigh. Acute prominent engorged abdominal superficial collateral veins were also seen.

Venous Doppler Ultrasound (VDU) showed left DVT extending from popliteal vein to common iliac vein.

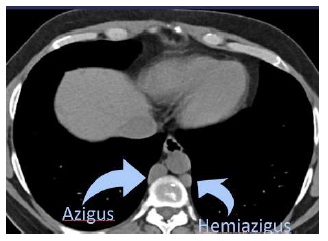

A CT showed agenesis of the infrarenal segment of the IVC and patent renal veins draining in to the azygous system on the right side and hemiazygous on the left side (Fig. 1 and 2).

The patient was discharged with rivaroxaban and compression stockings. At 2 month follow up the patient was still anticoagulated and asymptomatic.

Clinical case 2

A 35 years old woman, with a previous history of recurrent lower limb varicose veins surgery and left internal malleolar ulcer presented at medical department with complains of ulcer recurrence. She had no other medical or surgical history and was not taking any medication. On physical examination she had a left internal malleolar ulcer without varicose veins.

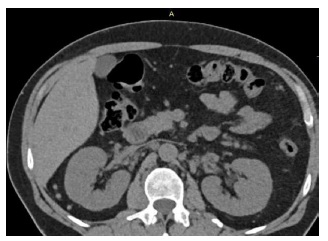

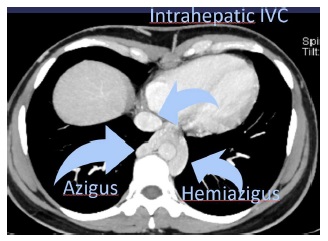

A CT was order and revealed infra-renal, renal and suprarenal, IVC agenesis with preservation of the intrahepatic segment and exuberant collateralization (lumbar venous plexus draining into azygous and hemiazygous systems; epigastric and internal mammary veins of right predominance). (Figure 2, 3 and 4)

The patient initiated dressing care with oxide zinc and oral rivaroxaban. During the follow-up she developed a right popliteal DVT, after inadvertent anticoagulation discontinuation, having restarted hipocoagulation.

Discussion

Some common features of patients with IVCA are young age (mean age of 30 years) and male gender7.

The majority of patients with IVCA remain asymptomatic because of the extent of collateral venous network in the abdomen and lower extremity (azygous, hemiazygous, lumbar, para-vertebral, and abdominal wall veins)2.

However, as we observed in clinical case 1, there will always be venous stasis compared to the general population2 and so, when symptomatic, the majority of cases present clinically as proximal DVT7.

The thrombosis preferentially involves the iliac and femoral veins, often bilaterally, and usually occurs after exposure to a precipitating factor (physical trauma or injury, prolonged immobility, use of birth control pills)8. Pulmonary embolism is a rare complication of DVT in IVCA, probably due to the small diameter of the vessels leading to the pulmonary circulation in the absence of the IVC8. However there are some reports of pulmonary embolus associated with IVCA, the possible explanation being that enlarged azygous or hemiazygous veins could act as conduits for emboli to the pulmonary circulation.

IVCA may also favor chronic venous insufficiency with development of ulceration as we observed in the clinical case 23.

Ultrasonographic doppler scanning is usually the first imaging modality in the evaluation of patients with DVT, but anomalies of the IVC may be missed6.All young patients presenting with idiopathic DVT should be investigated for inferior vena cava anomalies with CTA or MRI if ultrasound does not visualize the inferior vena cava7. Imaging criteria for IVCA diagnosis were the absence of the IVC lumen, associated with evidence of connection of the existent caval segment to the azygos system, and identification of venous collaterals (paravertebral venous system and its communications with the ascending lumbar veins and azygous-hemiazygous systems; gonadal, periureteral and other retroperitoneal veins; abdominal wall veins; hemorrhoidal venous plexus; and the portal venous system). It is possible to differentiate between an old thrombosis and IVCA: venous collaterals can sometimes be found in both entities, so the caval lumen should always carefully be sought (missing caval lumen in IVCA, while the lumen of an old thrombosis is usually narrowed, resembling a hypotrophic vessel) 4,8.

Venography is the gold standard for imaging diagnosis, but it is also highly invasive9.

Additional congenital anomalies have been associated with IVCA and involved aplasia/hypoplasia of the right kidney, situs inversus, congenital heart diseases, polysplenia and asplenia7.

Optimal treatment of DVTs associated with IVCA is unclear. The rarity of IVCA precludes performing clinical trials to determine the best treatment strategy and case series are likely the most informative7.

Once diagnosed, aggressive treatment must be started because of the high risk of post-thrombotic syndrome, but the length of treatment with vitamin K antagonist and the use novel oral anticoagulants are a matter of debate. A 2010 case series, the largest to date, compiled a list of 72 patients with IVCA-associated DVT. Nearly all of these 72 patients were treated with long-term warfarin but the length of anticoagulation varied. Considering the irreversible risk for future thrombosis, lifelong anticoagulation may be necessary10,4 Elastic stockings support and leg elevation should be also suggested, as well as avoidance of additional risk factors such as prolonged immobilization and oral contraceptive use9.

In some cases, venous recanalization by thrombolysis can be a good alternative particularly in the younger patients because of their higher risk of long lasting disability.

If medical treatment fails venous bypass graft/stenting should be considered. Venous bypass graft from the common iliac vein to the azygous vein or proximal cava segment is considered to prevent DVT or to heal the ulcers if conservative treatments fails10.

Conclusion

IVCA is a rare congenital abnormality that should be suspected when confronted with a typical clinical pattern, particularly a young patient [< 30/40 years old], especially males, with proximal DVT after intense physical exertion. Ultrasonography is not useful for IVCA diagnosis but CT scans and/or MRA can provide the diagnosis. Prolonged, perhaps even life-long anticoagulation, is usually prescribed along with elastic stockings.