Introduction

In 1961, Stevenson et al reported the first use of descending thoracic aorta (DTA) inflow for aorto-iliac reconstruction,1 but at the time, axillo(bi)femoral bypass was more popular due to its simplicity with reasonable outcomes, overshadowing the DTA as inflow. Currently, endovascular treatment is the preferred method for most aorto-iliac lesions, including complex cases, due to the development of successful new techniques.2 The standard aortobifemoral bypass (AbFB) is now generally applied when endovascular treatment is not feasible. In some cases, however, AbFB is not suitable due to circumferential aortic calcification or complex lesions involving the mid-visceral aorta precluding safe clamping of the abdominal aorta. Bypass procedures using the DTA as inflow have been described as alternative interventions in patients with hostile abdomen or as an alternative inflow source when graft failure/infection has occurred with past published studies reporting reasonable outcomes. The study aims to assess the current state of research on DTA inflow, its advantages, and limitations to guide clinical decision-making.

Methods

The authors performed a thorough electronic search of the literature using PubMed and Embase databases. The key words used in the search strategy were the following: (descending thoracic aorta) AND (bypass OR inflow) AND (aortoiliac lesions).

Only articles in English published in the last 30 years were included. After duplicates removal, titles and abstracts were screened and all potentially relevant articles were included for full text assessment. Only original research was included, but case reports and case series were allowed.

Review

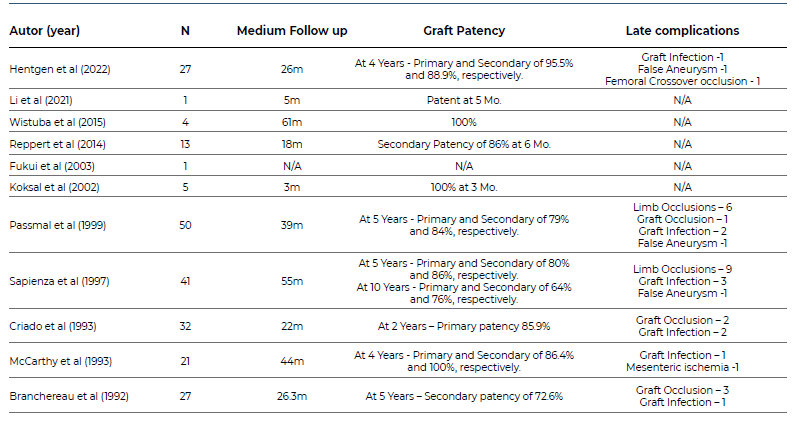

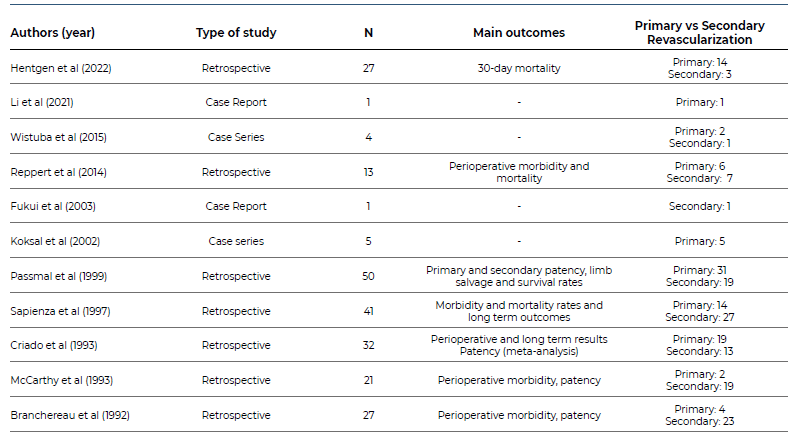

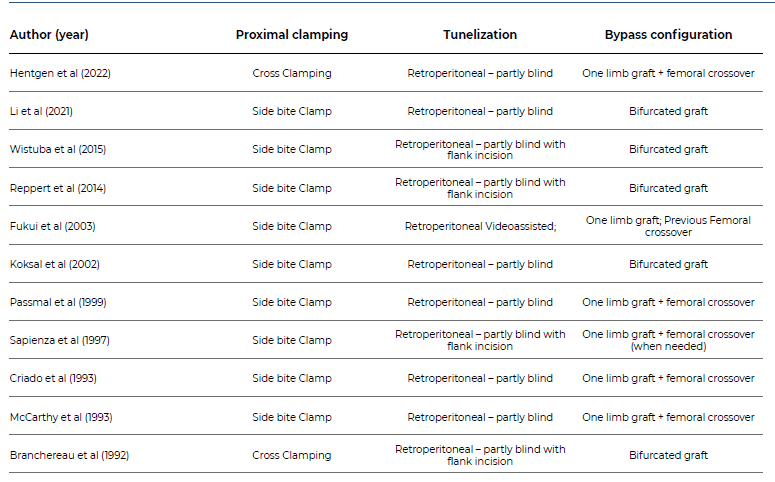

The authors selected 11 articles to compose the review (Table 1).3-12

Table 1 Summary of publications reporting on revascularization with inflow from the descending thoracic aorta, included in the literature review.

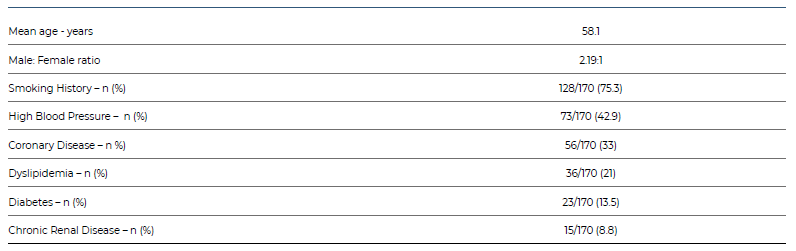

Demographic data analysis showed that the majority of patients (68.6%) were male, with an average age of 58.1 years. Prevalent comorbidities included smoking history, high blood pressure, coronary disease, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and chronic renal disease (Table 2).

Table 2 Summary of demographic data of patients with revascularization procedures using the descending thoracic aorta as inflow, included in the review

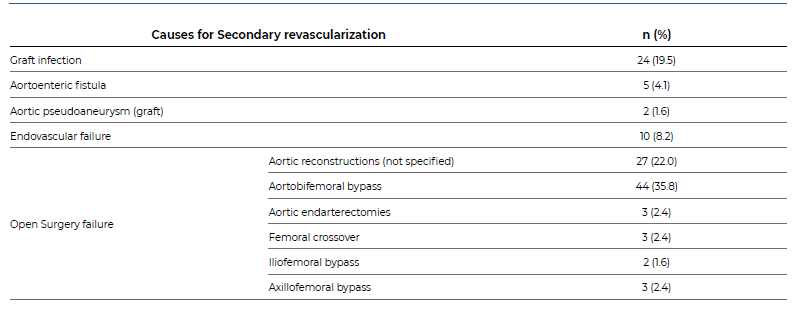

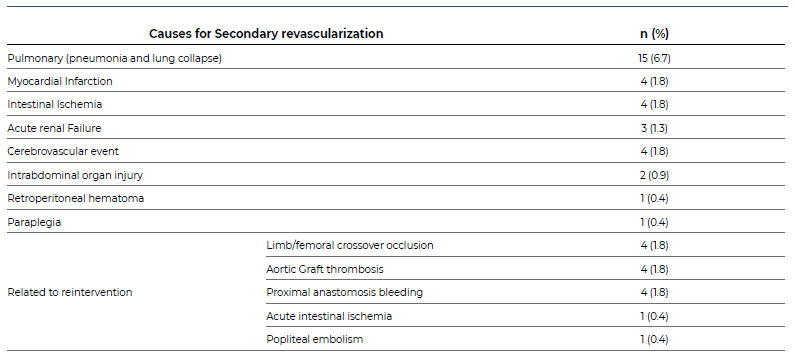

DTA inflow was used as primary revascularization in 99 patients (44.6%) and as a secondary option in 123 patients (55.4%). From the latter group, the indication for surgery were as follows: aortic graft infection in 24, aortoenteric fistula in 5, aortic pseudoaneurysm in 2, failure of previous endovascular procedure in 10, and failure of previous open surgery in 82 patients (Table 3).

Table 3 Causes for secondary revascularization procedures using the descending thoracic aorta as inflow, included in the review (N=123).

Surgical technique details (Table 4) were gathered, and side bite clamping was the preferred method for proximal aortic control. The graft, either unigraft or a bifurcated one, is usually tunneled through the retroperitoneal space in a partly blind way and anastomosed distally to the femoral arteries. A lumbar flank counter incision is suggested by some authors to help guiding the graft and avoid intra-abdominal organ injury.

Table 4 Summary of surgical technical details used in patients with revascularization procedures using the descending thoracic aorta as inflow, included in the review

The 30-day mortality rate was 4% (9/222) and fourteen patients (6%) needed reintervention due to a thrombosis event in 8 and bleeding events in four. Thirty-one per cent of the complications were lung-related, the most frequent acute complication (Table 5). Graft thrombosis and infection were the most reported long-term complications reported (Table 6). Secondary graft patency at 5-years was reported to be higher than 86%, except in Branchereau et al who reported a 72.6% of graft patency. At 10 years, Sapienza et al reported a primary and secondary of 64% and 76%, respectively (Table 6).

Table 5 Complications and cause of reintervention in patients with revascularization procedures using the descending thoracic aorta as inflow, included in the review.

Discussion

In an era where endovascular approach has become progressively the first option even for TASC D lesions, we should always keep in mind the durability of open surgical reconstruction. There are three specific situations where DTA inflow should be thought thoroughly: severe circumferential juxtarenal/suprarenal aortic calcification, failed aortofemoral bypass or endovascular first approach with no favorable anatomy for direct reconstruction and when concomitant visceral atherosclerotic disease is present and in need for revascularization.

This review shows favorable results of DTA bypass with similar mortality, morbidity rates, and graft patency compared to AbFB. Arguments against DTA inflow source are the invasiveness and the higher risk of complications. Even though, DTA bypass has evolved over time, with the possibility of performing it with minimal invasive techniques such as minimal thoracotomy or even using videoendoscopic. These advancements can potentially reduce the most frequent and feared pulmonary related complications. Ultimately, the decision to use it should be made on a case-by-case basis, considering the patient's individual functional status, age, comorbidities and the expertise and resources available at the medical center. These advancements can potentially reduce the most frequent and feared pulmonary related complications.

Even though DTA inflow is typically used as an alternative, this paper highlights the low perioperative morbimortality and good long-term patency rates, supporting its use not only as an alternative but also for primary revascularization in selected cases. The DTA is less prone to atherosclerotic disease and its approach avoids intrabdominal organ injury. Moreover, spinal cord, mesenteric, and renal ischemia are less likely given that partial clamping is a viable option. While the DTA inflow technique can be an effective treatment for aorto-iliac occlusive disease, it is a complex and technically demanding procedure that requires significant surgical skill and experience. Recent data on this procedure are lacking. Therefore, more studies to compare other endovascular and direct open surgical options are needed in order to define the indication for a DTA inflow use.

In conclusion, DTA can be used safely as an inflow for lower-limb revascularization and it remains an important tool in the vascular surgeon's armamentarium.