Introduction

Kidney and renal pelvis cancer is the 9th most common cancer in the USA, and the majority are renal cell carcinomas (RCC). An unusual hallmark of RCC is the predisposition for vascular invasion, with the extension of tumoral thrombus into the IVC up to the right atrium. This feature is also observed in tumors of the adrenal glands or hepatocellular carcinomas. These features are relatively infrequent and have therapeutic and prognostic implications1,2 This occurs in nearly 10-25% of patients with RCC.3 The natural history of untreated RCC with venous tumor thrombus is poor, with a median survival of 5 months and a 1-year survival of only 29%.4 Conversely, others have demonstrated significant survival improvements following radical nephrectomy and IVC tumor thrombus removal.5 Therefore, surgical excision and venous thrombectomy have become the mainstay of treatment in those capable of sustaining surgery. We report a case of renal neoplasm with a vena cava tumor thrombus treated with surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Case report

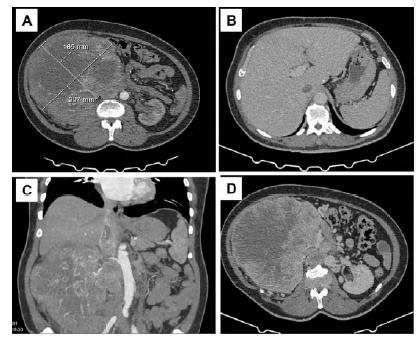

We report a case of a 53-year-old overweight woman, otherwise healthy and under oral contraceptives. The patient presented to the emergency department due to gross macroscopic hematuria episodes, episodic abdominal pain, and lower limb swelling. The physical exam revealed a large, non-tender, non-pulsatile abdominal mass, mild bilateral malleolar edema, and macroscopic hematuria. Her family history was negative for abdominal pathologies. The gynecological exam was negative for common pathologies. A computed tomographic for further clarification was performed (Figure 1). A giant right renal tumor (105x207mm) with thrombus invasion of the inferior vena cava up to the retro-hepatic IVC (level II, Figures 1B-1D) was noted, along with pre-caval and latero-caval adenopathies.2

Figure 1 Preoperative computed tomography angiography. Right renal tumor (A-D) with thrombus extension to the retro-hepatic inferior vena cava (B-D)

After a multidisciplinary discussion (oncology, urology, and vascular surgery), radical nephrectomy, IVC thrombectomy, and lymph node excision were proposed as a combined surgical effort between vascular surgeons and urologists.

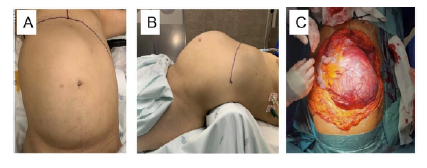

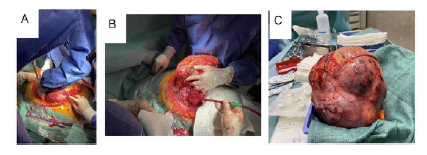

The patient was positioned in dorsal decubitus (Figure 2A-B), and a bilateral subcostal incision (Chevron) was performed (Figure 2C). The right kidney was mobilized, the renal artery and vein ligated, and a radical nephrectomy was performed in standard fashion (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 2 Intra-operative image with positioning in decubitus dorsalis. A large right-sided abdominal mass is noted (A, B). After a bilateral subcostal incision, a giant right renal tumor is noted (C).

Figure 3 Intra-operative images. After bilateral subcostal incision, a "giant" right renal tumor is noted (A, B). Nephrectomy specimen (C).

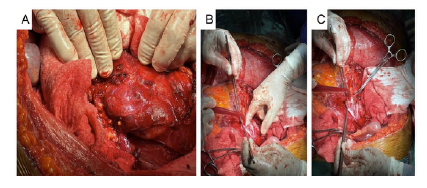

Perivascular (pre-caval and laterocaval) lymph nodes were excised. The IVC was exposed, and lumbar tributaries that tether into the posterior aspect of the infra-hepatic vena cava were carefully ligated to achieve circumferential IVC control (Figure 4A).

Figure 4 Intra-operative images of the inferior vena cava thrombus removal. IVC exposure (A) Longitudinal cavotomy and blunt finger dissection of the tumor thrombus from the aortic wall (B) Dissected thrombus (C)

Supra-hepatic IVC exposure was deemed not necessary. After IVC clamping, a longitudinal cavotomy was performed, and the tumor thrombus was excised. It was found not significantly adherent to the IVC wall and was easily removed by gentle blunt circumferential dissection and manual traction (Figure 4B-C). The cavotomy was closed with a running polypropylene suture. No significant hemodynamic shifts were noted during IVC clamping. The abdominal wall was closed in standard fashion, and a drain was left in place. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the eighth postoperative day. Pathology revealed clear cell renal cell carcinoma and lymph node metastasis. In the early postoperative follow-up, she developed multiple liver and lung metastases. She is now under adjuvant immunotherapy, although maintaining an adequate functional status.

Discussion

Venous migration and tumor thrombus formation are unique aspects of renal cell carcinoma. The presence of tumor thrombus is variable, and classification schemes have been developed to stage this aspect of the disease, Table 1.

Other than a prognosis marker, the presence and extent of IVC thrombus correlates with the technical demand of the surgical resection. The use of computed tomography angiography has also been well-established in this disease. It depicts full thrombus extension and detailed anatomical relationships, thereby aiding in the optimal surgical planning, particularly in those with level III and IV thrombus, which will require extended venous dissection (supra-hepatic IVC or intrathoracic IVC/right atrium), cardiopulmonary bypass or even circulatory arrest.6 Magnetic resonance imaging can further detail IVC wall invasion and thrombus mobility. Other than thorough preoperative planning, other measures have failed to overcome specific procedure-related complications. In particular, the impact of preoperative IVC filter implantation has been previously addressed. No significant benefits have been shown. They may also become incorporated into the tumor thrombus, significantly increasing procedural complexity. This step is not usually considered in our center.

Most authors prefer to perform IVC thrombectomy after renal artery ligation but before completing the radical nephrectomy. We were not able to perform the procedure in this usual fashion since the tumor volume made us unable to safely expose the IVC without completing the nephrectomy.

Invasion of the IVC wall by tumor thrombus is also indicative of additive risk for disease recurrence and poor prognosis.7 Renal masses with tumor thrombus invading the IVC wall, regardless of proximal extension level, are classified as T3c, which equates to level IV thrombus extension (above the diaphragm).9 In our patient, macroscopically, no venous wall invasion was verified in the intraoperative period. Others have reported that if IVC wall invasion is verified, the prognosis may not significantly worsen.11 In those with systemic involvement, 5-year survival following nephrectomy and thrombectomy ranges from 40-60%, significantly improving compared to those left untreated (median five months survival).8,10 Therefore, surgical treatment should always be considered in this group of patients. While radical nephrectomy with venous tumor thrombectomy remains the gold standard in this setting, the use of targeted agents in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting has been increasingly discussed. However, there remains a lack of consensus regarding its effectiveness and clinical utility.

Table 1 Classification scheme of IVC thrombus extension in renal cell carcinoma, according to the Mayo Clinic staging system.

| Tumor Thrombus Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| 0 | Tumor thrombus is limited to the renal vein and is detected clinically or during the assessment of the pathological specimen. |

| I | Tumor thrombus extends into the IVC, <2 cm above the renal vein |

| II | Tumor thrombus extends into the IVC, >2 cm above the renal vein but below the hepatic veins |

| III | Tumor thrombus extends above the hepatic veins but below the diaphragm |

| IV | Tumor thrombus extends above the diaphragm, including atrial thrombus |

Conclusion

Surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma can be challenging, particularly when concomitant vena cava thrombus is present. The combination of efforts between oncologists, urologists, and vascular surgeons can improve patient safety and perioperative outcomes with significant improvements in overall prognosis.