Introduction

Frailty is a complex age-related condition which is associated with the decline of physiological capacity and increased vulnerability to stressors, both endogenous and exogenous. It is also associated with an increased risk of hospitalizations, mortality, and reduced quality of life.1 Frailty has also been associated with rising healthcare costs.2 Weighted prevalence of frailty in patients ≥ 65 years has been reported to be 13%.3

Definition of frailty revolves around two main concepts: the frailty phenotype based on Fried et al and the accumulation of deficits. The Fried phenotype includes 5 domains: weight loss, reduced activity, slow gait, exhaustion and weakness.4 The accumulation of deficits, which can be measured using the Frailty Index, includes pre-defined health related deficits (comorbidities, symptoms, disabilities and laboratory parameters).5,6 Multiple tools, largely based on the previous concepts, have been proposed in assessment of frailty.7However, substantial heterogeneity exists in frailty assessment in vascular surgery, and no specific tool has been proposed.8

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients, especially on hemodialysis, have been reported to have high prevalence of frailty, with a recent meta-analysis reporting a pooled prevalence of 46%.9 This has been proposed to be due not only to an ageing population, but also to the higher incidence of comorbidities related to frailty.10 Frailty in hemodialysis patients has been associated with increased hospitalization and mortality.10,11 It has also been linked with depression in this population.12

Vascular access (VA) disfunction in hemodialysis patients has been reported as a risk factor for cardiovascular events and mortality.13 Early loss of patency has been associated with increasing age and comorbidities such as diabetes and coronary artery disease, also commonly related with frailty.14 However, the association of frailty and worse outcomes after VA creation have not been widely reported. The aim of this scoping review was to explore how frailty in VA patients is assessed and how it influences outcomes such as maturation and patency after VA construction.

Methods

A search was conducted on PubMed, Scopus and Cochrane using the following query: "vascular access" AND "frailty". Databases were queried from inception until date of search. Search was conducted on the 5th of May of 2024. Publications both in English and Portuguese were considered. Case reports and conference abstracts were excluded. Primary objectives were to evaluate frailty assessment methods and to study the influence of frailty on outcomes of VA for hemodialysis. Identified papers were exported into an electronic citation management software program to remove duplicates and to be assessed for full review. Reference lists were searched for additional publications.

A total of 658 articles were retrieved. After removing 67 duplicated articles, 591 articles were assessed for eligibility. After analysis, 7 articles on frailty and outcomes of VA in hemodialysis patients were included for analysis.

Results

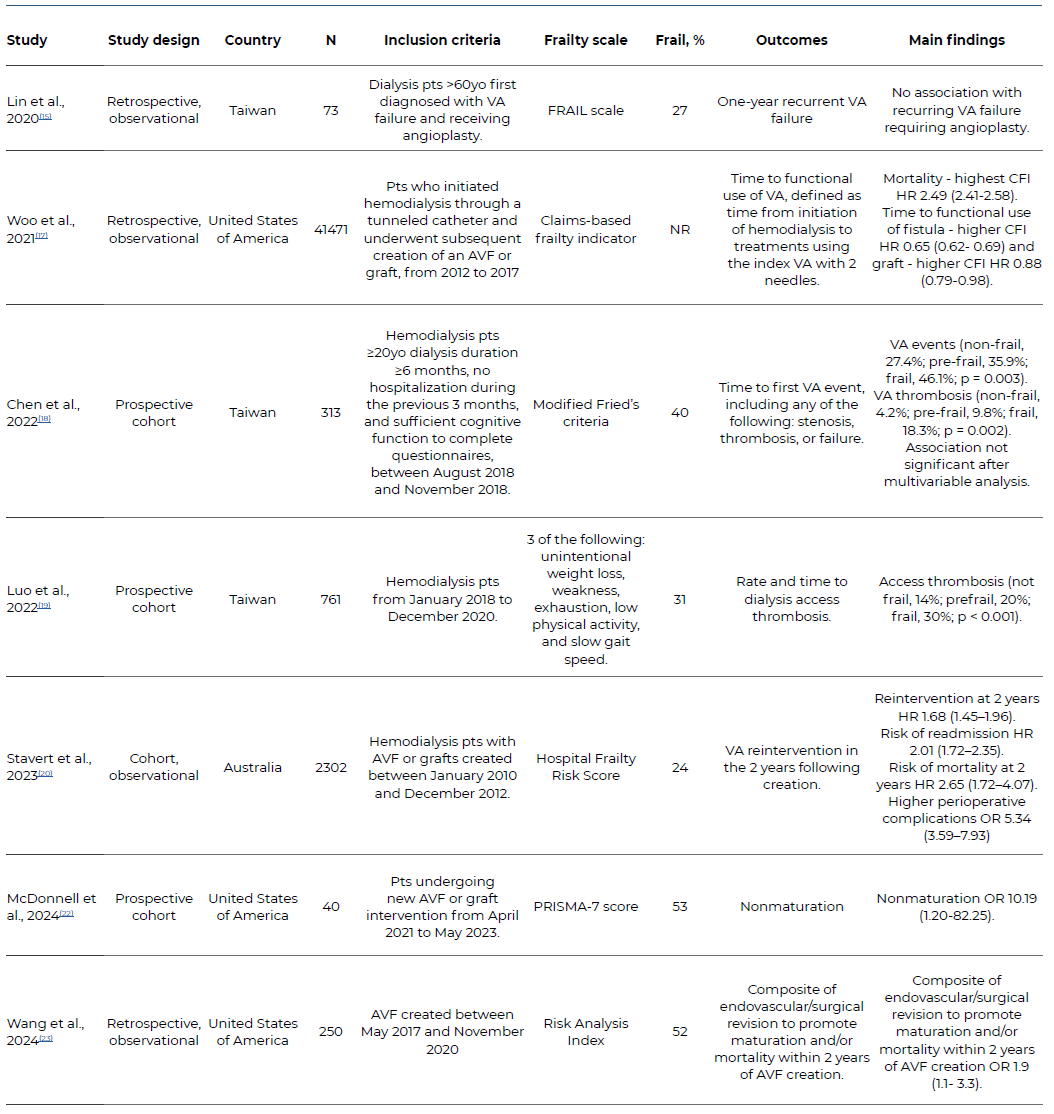

A total of seven studies were included. Study characteristics and results are summarized in Table 1. Patients included ranged from 40 to 41471. Frailty prevalence ranged from 24 to 53%. There was considerable heterogeneity in frailty scales used. Lin et al.15 used FRAIL scale, as previously described by Wei et al.,16 which is based on 5 components including fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness and loss of weight, with a ≥3 score indicating frailty. The study by Woo et al.,17 which included patients in the US Renal Data System database, used the “claims-based frailty indicator” (CFI) , which is a claims-based disability model that uses Medicare claims data and is anchored to Fried phenotype.4 Chen et al.18 used modified Fried’s criteria,4 using the Study 36-item Short Form (SF-36) and International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) questionnaires to assess slowness and weakness (2 points), exhaustion (1 point), low physical activity (1 point) and shrinking (1 point), with ≥3 points being considered frail. Luo et al.19 also used the phenotype criteria, with unintentional weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, low physical activity, and slow gait speed, again with ≥3 points being considered frail. Stavert et al.20 used the Hospital Frailty Risk Score as described by Gilbert et al,21 which uses a summary score calculated from 109 frailty ICD-10 scores, and stratifies in low, intermediate and high frailty risk. McDonnell et al.22 used PRISMA-7 questionnaire, which includes 7 questions related to age, sex, health problems, level of functionality and use of walking aids, with a score ≥3 being classified as frail. Wang et al.23 used the modified Risk Analysis Index (RAI) based on Vascular Quality Initiative variables including sex, comorbidities, residence type, and functional status24

Included patients also differed in the studies identified. Chen et al18 and Luo et al.19) included hemodialysis patients and analyzed VA outcomes on this population. Woo et al.17 included patients who initiated hemodialysis through a tunneled catheter and underwent subsequent creation of an arteriovenous fistula or graft. McDonnell et al.20 and Stavert et al.20 included patients undergoing new AVF or AVG intervention. Lin et al.15 included dialysis patients over 60 years of age who were first diagnosed with VA failure and received angioplasty. Wang et al.23 included all AV failure created at a single institution.

Lin et al. reported no statistically significant difference in frailty scores between patients with or without recurrent VA failure, which was defined in this study as stenosis requiring ≥1 angioplasty within 12 months due to access dysfunction. However, when assessing individual components of the frailty score, fatigue and weight loss were significantly higher in the recurrent VAF group.15

Woo et al. reported a longer time to functional use of both fistulas and grafts in the higher CFI quartile. The higher CFI quartile was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.49 for overall mortality, with 22.4% and 50.5% of these patients dying within 6 and 12 months of their first hemodialysis session, respectively.17

Chen et al. reported higher VA events, defined as stenosis, thrombosis, or failure (abandonment or surgical revision) in frail patients. Differences did not remain significant after multivariate analysis. VA abandonment did not differ between frailty groups.18

Luo et al. reported higher access thrombosis in frail patients, which remained significant after multivariate analysis.19

Stavert et al. reported higher risk of reintervention, both endovascular as well as surgical, in higher frailty groups, remaining significant after multivariate analysis. A high frailty score was also associated with creation of a new arteriovenous (AV) access during follow-up and multiple access procedures. Patients in the higher frailty score also had an OR of 5.34 of perioperative complications, driven by higher risk of bleeding, wound breakdown and infection, cardiac complications, and delirium. Thirty-day mortality was higher in higher frailty groups but did not remain significant after multivariate analysis. Higher frailty risk groups had an HR of 2.65 for mortality at 2 years after AV access creation, which remained significant after multivariate analysis, and a two-fold risk of hospital readmission.20

McDonnell et al. reported association of frailty with non-maturation in both univariate and multivariate analysis.22

Wang et al. reported lower survival on frail patients (69% vs 87% at 2 years for frail and non-frail patients respectively, p < .001). Frailty was not associated with revision before AVF maturation. Using a composite outcome of revision to promote maturation and mortality, frail patients had an OR of 1.9 on multivariate analysis.23

Table 1 Characteristics and summary of main results of studies evaluating the effect of frailty on vascular access outcomes, included in the systematic review

VA: Vascular access; CFI: Claims-based frailty indicator, HR: Hazard Ratio, OR: Odds Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval,

AVF: arteriovenous fistula; NR: Not reported

Discussion

Frailty is prevalent in patients in dialysis and submitted to AVF construction, being as high as 53% in included studies, which is consistent with a recent meta-analysis of frailty on dialysis patients.9 However, considerable heterogeneity exists in frailty assessment, ranging from self-reported questionnaires to multimodal assessments including both self-report and using quantifiable data, to scores using clinical variables. There has been considerable research on the value of self-report and performance-based frailty scores. It has been reported that, while both measures indicate a higher mortality among patients on hemodialysis, self-reported frailty without performance-based frailty did not associated with higher mortality.25 Besides, frailty prevalence is higher when measured by self-reporting, including in ESRD patients.26 Authors have suggested using scores combining both self-report and performance-based measures when assessing frailty.27,28 However, no single frailty assessment tool in dialysis population has been proposed.

Three studies reported higher mortality in frail patients, which is consistent with published literature on dialysis patients.29-31 This may be due to accumulation of multisystem deficits, inflammation and risk of infection.32

All studies, apart from one, reported worse outcomes for VA in frail patients. Two studies reported higher access thrombosis in frail patients.18,19 Stavert et al. reported higher perioperative complications and reinterventions in frail patients.20 McDonnel et al. reported higher risk of non-maturation in frail patients.22 While the mechanisms are uncertain, it has been proposed that, similar to mortality, inflammation plays an important role in VA disfunction, as well as uremia and endothelial dysfunction. These mechanisms lead to increased proliferation and eventually stenosis of the VA.33 Furthermore, frailty has been associated with elevated inflammatory markers in ESRD patients, further explaining the link between frailty, inflammation and VA disfunction.34

The NKF-KDOQI (National Kidney Foundation-Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative) clinical practice guidelines suggest a patient centered approach to VA, considering patients characteristics and preferences.35 Frailty assessment might be an additional tool in the complex decision making regarding VA in dialysis patients, individualizing care in this specific population. Patients with higher frailty scores, which is related to higher mortality, lower maturation rates, and higher risk of VA reintervention, might not derive the same benefits of AV fistulas and grafts as non-frail patients, and this should be considered when assessing these patients. Woo et al. reported higher time to functional use of both AV fistulas and grafts in frail patients. However, while the association was in a dose-response manner for fistulas, it only occurred in the highest frailty quartile in grafts.17 The authors proposed that fistulas might be more adversely affected by frailty when compared to grafts, which may an additional factor to consider when choosing VA in these patients.

While this review is the first to our knowledge to summarize the current knowledge on frailty and VA, it is limited by heterogeneity of included studies, both in patients included, frailty assessment and outcomes measured.

Overall, these studies suggest that frailty assessment might aid in identifying high-risk patients for VA dysfunction and reintervention, as well as patients with low survival, which might influence decisions on VA type. More studies are needed to assess the most adequate frailty score in this population and to standardize reported outcomes, as well as identifying interventions that may reduce frailty and improve VA outcomes.

Conclusions

Frailty is associated with adverse outcomes of VA in dialysis patients, including thrombosis, longer time to functional use of access, and reintervention. Frail patients also have higher mortality after vascular access construction when compared to non-frail patients. Frailty assessment might aid decision-making discussions on ESRD patients about VA and help individualize choices on this population.