Introduction

Extra-cranial carotid artery aneurysms (ECAA) are rare and represent a therapeutic challenge for surgeons.1-3 An ECAA is generally defined as a dilation of the internal carotid artery (ICA) or common carotid artery (CCA) greater than 150% of the diameter of the adjacent healthy artery.1-3 The true incidence of ECAA is unclear, representing approximately 1% of all carotid artery surgeries.1 Although atherosclerosis is the most common cause of ICA aneurysms, connective tissue disorders may also predispose to ECAAA or dissection development by altering the vessel-wall structure, with degeneration of the tunica media and elastic lamina. Importantly, because of the high risk of embolic stroke or rupture, with a mortality rate of 70% if left untreated, ECAAA repair is recommended.3,4

We report the clinical course, radiological findings, and genetic assessment of a patient with an incidentally discovered ECAA.

Case report

A 65-year-old female patient was referred to our center due to a left latero-cervical swelling. She was a non-smoker patient with a history of previous hemithyroidectomy, splenectomy, hysterectomy and adnexectomy, aortic valve, and aortic root replacement due to aneurysmal pathology. She also had a positive family history of aneurysms, with her father having died from a ruptured infrarenal aortic aneurysm (AAA) at the age of 53 and her cousin currently in follow-up for pararenal aneurysm at the age of 44. At presentation, CTD had not been confirmed in either of her family members. No sensory-motor deficits or cranial nerve abnormalities were identified at the neurological examination.

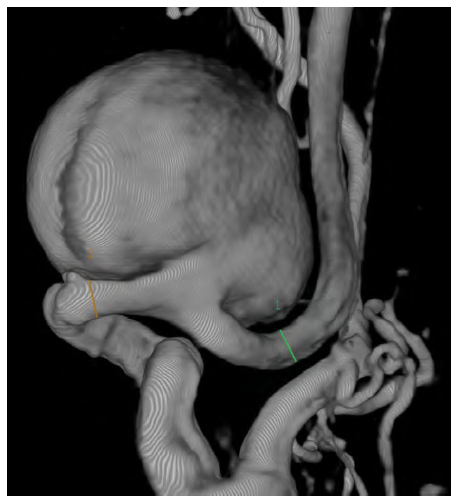

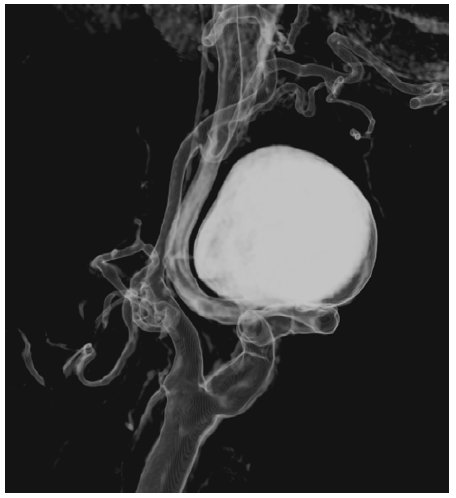

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed a saccular aneurysm of the left internal carotid artery with a significant tortuosity (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Preoperative computed tomography angiography reconstruction of the saccular internal carotid aneurysm

Figure 2 Preoperative computed tomography angiography reconstruction of the saccular internal carotid aneurysm

The aneurysm measured 28mm x 30mm and was located near the base of the skull, arising 30mm after the carotid bifurcation. The CTA had also highlighted significant tortuosity of the contralateral ICA but without aneurysmal degeneration. Because of the tortuosity of the ICA, not technically feasible for endovascular repair due to the diameter and absence of optimal distal neck, the volume of the aneurysm, and mass-related symptoms, open repair was preferred to endovascular exclusion as the latter (by excluding the ECAA with a covered stent or embolizing the aneurysm with coil spirals); would not address the mass effect and potential development of permanent cranial nerve injury.

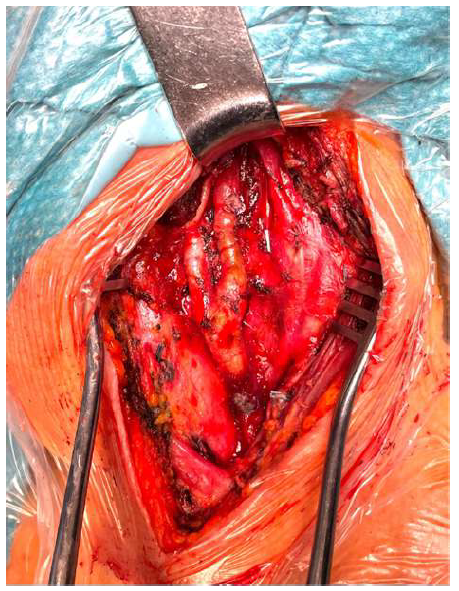

The patient was positioned supine with hyperextension and slight lateral rotation of the neck to the contralateral side; anatomical landmarks were identified and marked. She was intubated with an orotracheal tube and subjected to electroencephalographic monitoring during the procedure. The common carotid artery was isolated to obtain proximal control. The internal and external carotid arteries were also isolated to distal control (Figure 3). Once exposed, the aneurysm was carefully isolated, with gentle traction exerted proximally on the internal carotid artery to displace the caudal, thus improving access for distal (cephalic) control. During clamping, no changes in the EEG registration were identified. The aneurysm was resected, and the internal carotid artery was reconstructed in an end-to-end fashion with interrupted stitches (Prolene 6/0) (Figure 4). No variations to the electroencephalographic pattern were detected following clamp removal. A section of the carotid aneurysmal wall was excised and sent for histological investigation. After three days, the patient was discharged with no neurological issues or cranial nerve injury.

Figure 4 Intra-operative image revealing the reconstructed internal carotid artery following aneurysm resection

The histological examination showed cellular disorganization of the muscle cells of the tunica media with widespread deposits of mucoid extracellular matrix. The section of the artery also presented discontinuity of the elastic membrane with fragmentation, collapse of the laminae, and marked accumulation of matrix. The morphological findings were suggestive of severe degenerative connective tissue disease.

Discussion

ECAA are rare, accounting for 4% of peripheral aneurysms.1 Since Sir Astley Cooper’s first publication of proximal carotid artery ligation for treating a carotid aneurysm, the etiology, management, and results following aneurysm repair have evolved substantially. Despite the rapid advancement of endovascular techniques, open surgical repair remains the favored approach.5-6 Treatment is generally recommended for symptomatic or rapidly enlarging ECAA, infection, or when a diameter greater than 20mm is reached.7-17 The precise mechanisms leading to carotid artery tortuosity and degeneration are unknown. Several studies have suggested histopathologic alterations in tortuous carotid arteries, including degeneration of the tunica medium and elastic lamina, as the basis of the pathological process.7,12,15,18,19 Patients with tortuous arteries are frequently suspected to have some collagenopathy, but definite diagnosis is often inconclusive.

In turn, CTD has been shown to alter vessel structure and lead to vascular abnormalities such as aneurysms and dissections through various mechanisms, including altered fibrillin-1 structure in Marfan syndrome, collagen mutations in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), or transforming growth factor (TGF) signaling pathway abnormalities in Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS).19

Welby and colleagues described carotid artery tortuosity in 44% of patients with CTD. Tortuosity was frequently bilateral with 30% of all patients with CTD presenting bilateral ICA tortuosity.12 Among all, patients with Marfan syndrome had the highest prevalence of tortuosity (88%), followed by Loeys-Dietz syndrome (63%), type 1 neurofibromatosis (42%) and other vascular and nonvascular types of CTD (19%).

In particular, histopathologic alterations such as tunica media and elastic lamina degeneration were identified. Additionally, the presence of aortic root dilation or an ascending aortic aneurysm in combination with carotid artery tortuosity was highly associated with CTD with an odds’ ratio of 28 and a specificity of nearly 99%.12-13 These findings suggest that carotid artery tortuosity, particularly when combined with an ascending or root aortic aneurysm or dilatation, is strongly linked to connective tissue disease, as in the case herein reported.12

Marfan syndrome is determined by a defect in the structure of fibrillin-1, while LDS arises due to mutations in the TGF-ß protein receptor. Loss of microfibrils consequent to a defect in fibrillin-1 results in aberrant TGF-ß signaling, which is important for the proper formation of the extracellular matrix. Other connective tissue disorders, both vascular and nonvascular, are associated with collagen structure abnormalities rather than elastin.

According to a previous hypothesis, the extracranial ICA may be vulnerable as it represents a transition zone from an elastic to a muscular vessel.14-15 Given the higher prevalence of carotid tortuosity in patients with Marfan syndrome and LDS, as well as the fact that the mutated proteins in these two disorders are part of the same pathway affecting the biogenesis and maintenance of elastic fibers, it has been hypothesized that changes in elastic fiber structure, rather than collagen structure, are more important contributors to the development of tortuous and aneurysmal vasculature.

In our patient, the histological findings were suggestive of a severe degenerative disease compatible with a connective tissue disorder, which reinforces vascular tortuosity as a significant phenotypic component of CTD individuals.

Conclusion

Combination of ascending aortic aneurysm or aortic root dilation with any carotid tortuosity or aneurysm is highly specific for the presence of a CTD. The clinical history of the patient, as well as histopathology, are essential to diagnose and provide adequate management of CTD patients with arteriopathy. Close monitoring following ECAA repair is advised, particularly for individuals with contralateral aneurysms, kinking, or tortuous carotid arteries.