Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Medievalista

versão On-line ISSN 1646-740X

Med_on no.16 Lisboa dez. 2014

ARTIGO

The Tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches: the rediscovery of an iconographic program

Carla Varela Fernandes*

* Universidade de Coimbra, Centro de Estudos de Arqueologia, Artes e Ciencias do Património (CEAACP). Bolseira de Pós-Doutoramento da FCT (SFRH/BPD/76929/2011), Coimbra, Portugal. E-mail: carlavfernandes@mail.com

RESUMO

O túmulo (cenotáfio) de D. Rodrigo Sanches (filho ilegítimo do rei Sancho I) foi retirado recentemente do arcossólio que o acolhia no claustro do Mosteiro de S. Salvador de Grijó, desde 1626. Esta trasladação, que teve como principal consequência a possibilidade de visualização das restantes faces da arca tumular, bem como a melhor visualização do jacente e das outras figuras da tampa, trouxe ao panorama da História da Arte Medieval portuguesa interessantes novidades do ponto de vista iconográfico e também plástico/estético, já que todas as faces se encontram esculpidas. É por isso o momento de rescrever a análise desta obra de escultura tardo-românica, colocar agora em relação todos os temas aí representados, procurar descodificar quais as principais intenções do seu encomendador e, procurar a sua integração num universo geográfico mais amplo, do ponto de vista artístico (peninsular e transpirenaico). A responsabilidade de ser a primeira vez que a obra é estudada na íntegra, leva a que se coloquem propostas, hipóteses de interpretação, mais do que conclusões.

Palavras-chave: Tumulária; Românico; Adoração dos Magos; Apresentação no Templo; Calvário

ABSTRACT

The Tomb (Cenotaph) of D. Rodrigo Sanches (illegitimate son of King Sancho I) was recently removed from the arcosolium that housed it in the cloister of the Monastery of S. Salvador Grijó since 1626.

This transfer, which had as its main consequence the possibility of visualization of the remaining sides of the chest tomb, as well as the improved visualization of the tomb effigy and other figures of the slab brought interesting news to the panorama of History of Portuguese Medieval Art, from the iconographic point of view and also from the plastic/aesthetic point of view, since all faces are carved. Therefore, this is the moment to rewrite the analysis of this work of late-Romanesque sculpture, to place it regarding all the represented, to attempt to decode the main intentions of his commissioner and seek its integration into a broader geographic universe, from the artistic point of view, (peninsular and trans-Pyrenean). The responsibility of being the first time that the work is studied in its entirety leads to the presentation of proposals, interpretive hypotheses, rather than conclusions.

Keywords: Tomb Sculpture; Romanesque; Adoration of the Magi; Presentation in the Temple; Calvary

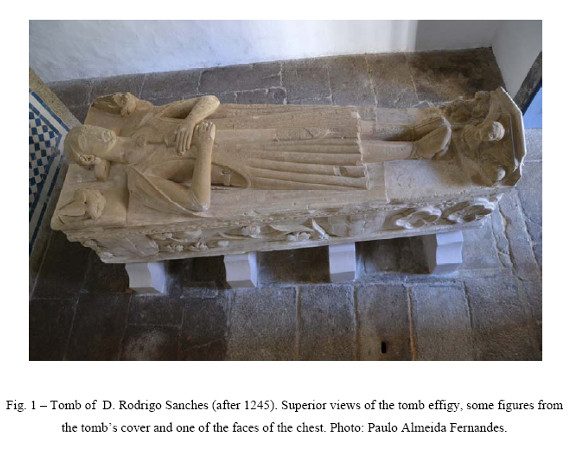

In August of the current year, the parish of Grijó, in the context of the process of restoration that has been in development in the church of the Monastery of S. Salvador, made the decision (long claimed by the scientific community) of having the tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches removed from the arcosolium (wall-niche) that housed it (I would even say that incarcerated" it) since 16261, situated in the cloister of the monastery2. Besides being closed there, it had a front grid that hindered the visualization of the only sculpted face that had always been visible to the public, as well as of the tomb effigy and of the remaining details of the tomb chest. (Fig. 1)

Therefore, any study of this late-Romanesque Portuguese work of art done up to this point, was always conditioned in what refers to the observation and to the knowledge of what actually constituted the iconographic program of the tomb, since, not only was it not possible to observe the various sides of the tomb chest, as descriptions of the tomb are totally laconic, with Friar Nicolau of Santa Maria being the most complete, and only states that it is a "high relief tomb, ordered to be made by his sister D. Constança Sanches, apart from the Gospel of the of the high chapel Church of the referred monastery ..."3.

It seems to have been also at that time that the laudatory epitaph, that always accompanied the tomb, disappeared. The textual content of this epitaph, according to Mário Barroca, should be of the responsibility of the Prior of the Monastery of Santa Cruz in Coimbra, D. João Pires, the same person to whom D. Constança Sanches commissioned the text of her own epitaph, having passed away in 1269 and buried in Santa Cruz de Coimbra.

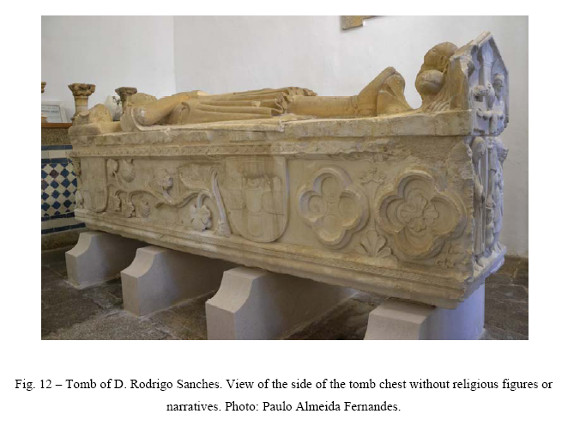

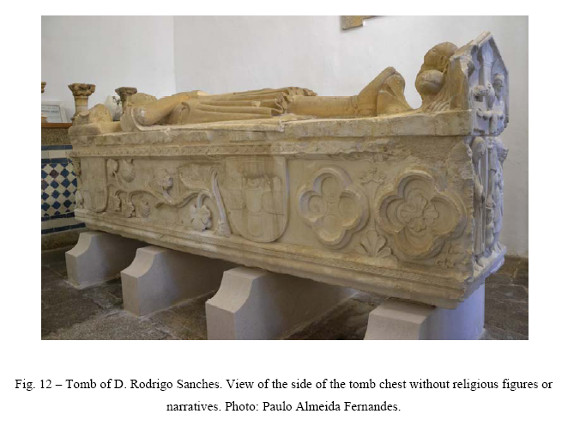

Thus, the novelty introduced by this removal is the possibility of being able to observe what is presented by the end sides and the other long side4: at one end, on the side corresponding to the head of the tomb effigy, are the scenes of Adoration of the Magi and The Presentation of the Child in the Temple and, at the opposite end, The Calvary, while the long face that touched the back wall of the arcosolium is decorated with two large heraldic shields, a vine, two shells (scallops), two quatrefoils with interior decoration and even a tiny lion heraldry feature. It is necessary, therefore, to resume studies on this work, reformulate ideas and propose new hypotheses of interpretation, goals that I propose to accomplish with this study, certain of the responsibility of those who study a work (or, better, the "new" visible parts) for the first time, and being aware that there are more assumptions to be made, than conclusions to be drawn. This study, due to the limitation of space, will focus exclusively on the analysis of faces that are now being rediscovered, and, when found necessary, reference will be made to the face that has already been studied and to the tomb effigy, considering that there is little to add to what has already been recently written5.

1. The a of the Redemption and of the Glory of Christ: Scenes of the Childhood

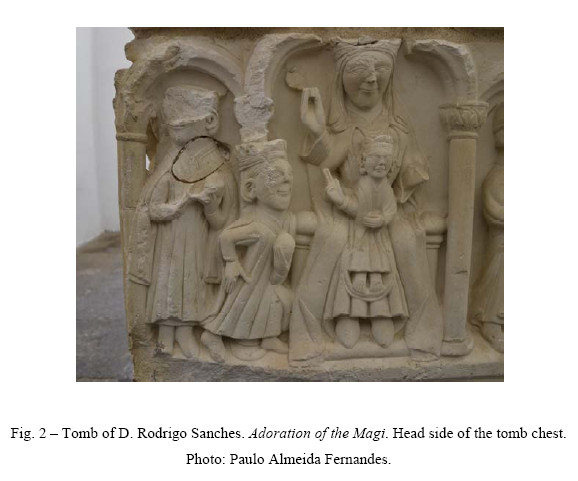

The face of one of the ends of the tomb chest, corresponding to the side of the head of tomb effigy is not filled by a scene with a single iconographic theme, as was usual, but by two scenes that illustrate two distinct themes, separated by a three lobe arcade. Both illustrate moments of the beginning of Jesus' earthly life. But the mentor (the iconologist) of the work and its executor dismissed the Nativity scene, a moment that emphasizes the environment of poverty/humility of Jesus' birth, or even the Adoration of the Shepherds, that is the provision of homage and recognition of the humble to the Saviour. In the first place, the moment of the Adoration of the Magi was considered: the three figures of ambiguous and complex interpretation, following the announcement of an angel and are directed by a guiding star to the stable in Bethlehem to pay homage (vassalage, to better understand the meaning that these characters and their gestures acquired at the time that this tomb was made) and giving gifts with strong symbolic meaning, the child, who was God-man, born poor, but recognized as the Messiah and as the King of Kings – the iconographic composition follows an established version since late antiquity. (Fig. 2

)

As in other examples of Romanesque art that narrate the Epiphany, both in painting (including illumination) as well as sculpture or jewellery, the scene consists often of two parts that seem independent from each other. This is due to the absence of visual or tactile connection between the group of three characters who come to pay homage and that are placed, in profile or at ¾ of the viewer (the Magi honouring the Baby Jesus) and the group formed by the Virgin Mary, enthroned, frontal and stiff, serves only as a seat, or throne, for the Baby Jesus, sitting on mother's lap, in the centre or on the left leg. The emotional bond between the Virgin Mary and Jesus is, in many works of Romanesque style and chronology, very limited or nonexistent.

This is what we can see, for example, in an altarpiece dated circa 1150, carved in limestone, of Overplays, or in a wooden altarpiece, from the mid-thirteenth century and of Italian origin (Latium, Altair - Church of Maria-High)6. In the picture on the peninsular Romanesque art, many examples can be cited of this expressive iconography, but if the Virgin and Child are, in general, throughout the twelfth century and the middle of the thirteenth century, represented frontally relative to the observer, the Baby Jesus tends to turn his head slightly in the direction of the Magi and pointing in that direction with one hand7.

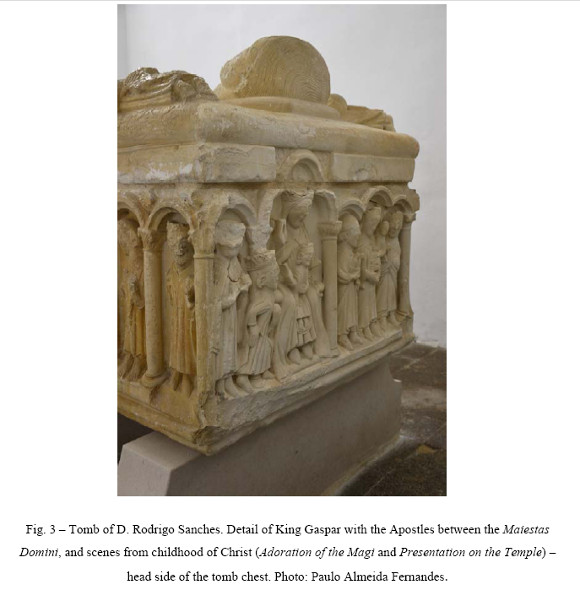

Now, the scene of the Adoration of the Magi from the tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches belongs to the Romanesque iconographic group in which the relation of the Virgin and Child with the Magi is not obvious. The three Magi have the peculiarity in this work, of occupying both sides of the grave: one of the Magi (Gaspar, the last of the line of the three kings that is placed sequentially for veneration), it is known today8 that it is the last figure that is represented in right corner of the long side/face, that for centuries was visible, very deteriorated, inserted over a round arch resting on columns. He is crowned and has his head in slight rotation, turning subtly to the next Magi (Balthazar). This is the first to occupy the left corner of the side/face from the top of the chest, also inserted in an arch with the same profile. (Fig. 3

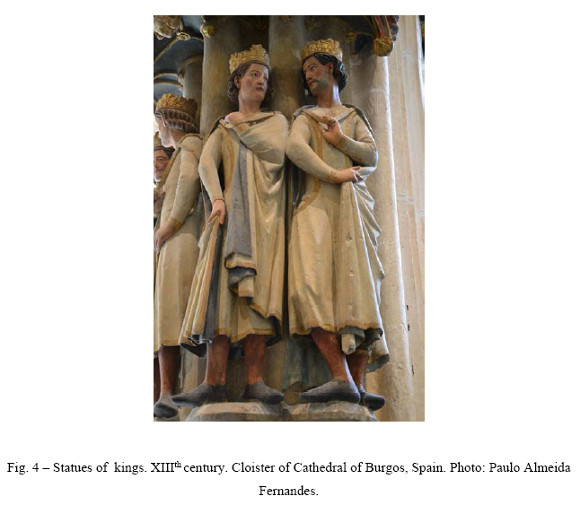

) Balthazar is standing with the body in the frontal position, but the head (now with great loss of matter) in rotation in the direction of the Magi that precedes him, establishes a symbolic visual connection with him, a kind of calling to the main reason for the visit, evidenced even by one hand pointing in the direction of the Messiah. With the other hand, he holds the pot with incense to offer the Saviour. The third magi Melchior, genuflected, has the peculiarity of having part of the body under the anterior arch, cover the shaft part of the dividing column between the arches and occupy, part of the space already covered by the three lobed arch (higher than all the arches represented on this face/side, surpassing even the field of sculpture of the chest), under which is the next group of figures. Melchior holds with one hand, the pot of gold that he offers to the Infant Jesus. All Magi wear tunics and long triangular necklines, and on this most common piece of clothing, the pelisse is displayed with its wide openings for arms, thus repeating the same piece of clothing that the effigy of D. Rodrigo wore over the armour9, following a style in vogue in the Peninsula for much of the thirteenth century10. The tunics and pelisses have deep pleats deep that, as in almost all the outfits of the figures of this tomb, make a slight retraction in the waists, nearly always without belts to fasten them, and, finally, wear equally long mantles that they fasten on the chest with cloth strips. The crowns that identify the Magi as kings are opened and decreased (very much damaged, but still perceptible). (Fig. 4)

It must be noticed also that there was no intention, on the part of the iconologist and/or of the artist, in characterizing the ages of Three Kings, something that, in these years, was already possible to see in some works of the Romanesque art and even of the beginnings of the Gothic (already imposed in France and in works of a larger artistic demand produced in some peninsular kingdoms), situation that, among us, will only be seen happening in the fourteenth century and then, more clearly, in the fifteenth century11. Here, three men are beardless; they have similar hairs (to the length of the ears) and no facial characterization that should indicate a more advanced age in any of them.

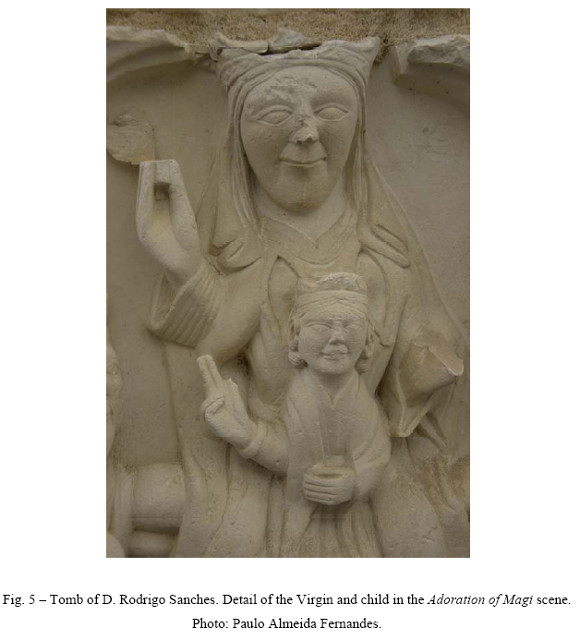

In this scene, the Virgin Mary is an image in Majesty and is, in general, similar to many other Marian depictions of the time and earlier: crowned, enthroned on a Romanesque throne-like seat, majestic, serving as a throne to Baby Jesus and holding, with one hand, what, by the size and format of the still existing remains, would be a fleur-de-lis, constituting both (crown and fleur-de-lis) evident symbols of his kingship12. These attributes recall, the genealogy of Mary, just as S. Joseph, also has its origin in the House of David13, in other words, it emphasizes also the royalty14 of Jesus himself, who cannot stop contrasting with the poverty that characterized his birth (Nativity) and up to the Presentation in the Temple. The idea is underlined in this scene with the presence of other royal figures (crowned), the Magi, who are, one by one, in worship and recognition of the King of Kings.

Noteworthy in this Marian representation is the fact of the Virgin having, in the superior part of the dress or tunic, two vertical openings made at the place of the breasts, leaving the nipples visible, in a symbolic allusion to the breastfeeding of the Baby Jesus by the divine Mother, in other words, one of many formulas conceived by the different artists since late Antiquity (still in the Romanesque art, but with larger development in the Gothic art) of what commonly is designated by Madonna of the Milk. But Baby Jesus, in this image of total Romanesque form, is seated to the centre of the lap of the Virgin, also has the head crowned by the same type and model of crown, is making the gesture of the blessing with one of the hands and placing the feet on some artificial, semi lunar folds, and it does not present any gesture, any suggestion, of searching of the motherly breast. This is, therefore, a subtle iconographic resource, meant to join several messages of great spiritual and symbolic meaning in the same composition. (Fig. 5

)

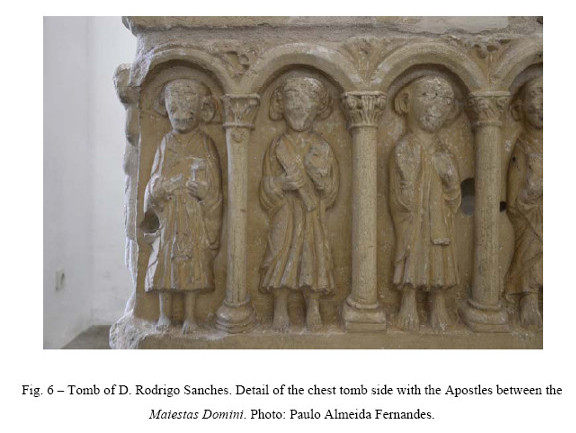

In this scene (as in the next scene of this side or the one that is represented on the other end of the tomb chest), the facial characterizations of different figures do not differ significantly among themselves, but rather suggest the use by the sculptor of the same physiognomic pattern, which served to represent male and female figures (changing slightly the hair or a few props) and has evident particularities, such as the excessive size of the heads in their anatomical relationship with their bodies, very large almond-shaped eyes (as we also see in the face - although very deteriorated – of the recumbent effigy of Rodrigo Sanches)15, very large and protruding ears and somewhat prominent mouths with a slight upward stroke, which, in some cases, as we shall see, seems to suggest a not very obvious smile. These elements are, in all, the marks of authorship, and are suggested on the figures of the apostles on the long side, but the marks of erosion, caused by different atmospheric conditions and human carelessness, didnt allow people to perceive them that clearly. Also, we can now realize that the type of tunics (long and always with not very pronounced triangular necklines, slightly raised and forming discreet collars) with its wide and deep pleats that help to make the silhouettes with narrow waists, are totally noticeable figures in the scenes the tops of the chest, but relate in everything to the highly eroded tunics of all the apostles and Christ in Majesty. (Fig. 6

)

Inside the arch, and on the crowned head of the Virgin, was carved the guiding star, in bas-relief, more complex and highlighted than the two six-pointed stars placed in circles16 and punctuate a fictitious sky, outside the arch, covering the sculpture field the tomb lid. Above these, also on the lid, the representation of the Moon, also in very low relief.

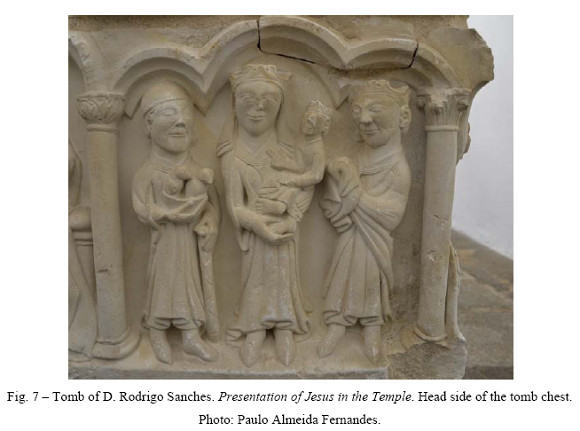

The scene that follows - Presentation of Jesus in the Temple - closes the narrative cycle devoted to the Infancy of Christ. Before proceeding with its analysis, it should be noted that, throughout the Portuguese tomb and retable sculptures of the 12th - 14th centuries (including in illuminated manuscripts), this is the only work with the figuration of this important theme of Life of the Virgin and the Infancy of Christ which helps to differentiate this work in relation to its predecessors, and even in relation to those that followed17. The theme of the Presentation of the Child in the Temple is the festival celebrated on February 2, forty days after the Nativity, and is mentioned only in the Gospel of Luke (2:22-4), continuing what was defined in the law of Moses (Exodus 13:2) and that forced all Jews to consecrate the firstborn to the Lord, in commemoration of the departure from Egypt, to redeem them by a canon of five cycles and sacrifice a lamb. Mary and Joseph, like other poor couples then redeem their child by offering a pair of doves or pigeons18.

Also this scene on the tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches presents idiosyncrasies that need to be pointed out, if when we are comparing with others that, at the time, before or after this, were made throughout the space of Christianity. Note that the scene is composed of four figures with their iconographic attributes, all framed, once again, by a three-lobed arch, but with three lobes at identical heights, but does not have any props which comprise normally the scenic space where scene took place, and that help to the reading of the narrative. Let's see. (Fig. 7

)

In the usual scenes of the Presentation in the Temple, the child is standing on or seated on the altar, to signify that, from the birth, he is marked by his character of expiatory victim and predestined to a sacrifice19.

In this scene, an altar was not put between the figure of Simeon and the remaining characters, without establishing between them an obvious relation that it induces to a "classic" narrative of the subject. The essential characters are present and, only for their identification and gestures, we realize that we are before the moment of the Presentation in the Temple. Notice that Mary, the central figure, is the only one who is in a totally frontal position regarding the observer, holding the Child with one of the arms and supporting one of the feet with the other hand, as if a pedestal.

In this scene, once more, the Virgin, crowned, is the Queen of Heaven, serves as the throne to her son, and, once again, has the particularity of presenting at least one vertical slot on one side of the body of the dress, leaving the discrete short nipple uncovered, and repeating the symbolic intention that we've seen at the scene of the Adoration of the Magi. The Child is also in this scene, despite his position changing from full-frontal position to a ¾ position (but with the face turned frontally to the observer), in a position that provides for recognition, homage and worship of the faithful. In other words, neither Virgin, nor the Child are represented here in the usual positions and gestures that weve found in the overwhelming majority of the representations of this biblical moment, due to the absence of the altar.

At one end is the figure of St. Joseph, a character that becomes usual in this iconography from the 11th century. He is depicted standing to the right of the Virgin Mary, in identical clothing to that of the apostles represented on the long side of the tomb chest, and also alike the clothing of the other male figure that is part of the set of characters in this scene, and is characterized by the usual iconography: head covered with a kippah, the stick or Tau shaped rod secure in one hand, in the other hand he has a small basket, inside of which two doves are arranged for the offering to the Temple.

As I mentioned earlier, and again I emphasize, in Portuguese art of the 12th and 13th centuries, there are no other scenes with the same iconographic theme, so that we may evaluate, the presence and role of S. Joseph in the context of this iconography, as well. And if we do find it in peninsular painting, particularly in Catalan painting, the truth, however, is that in international medieval art of the century following the completion of this grave, the representations of S. Joseph among the figures that are within the Temple at the time of presentation of Jesus have become more rare, and the role that was once his, is assigned also to the prophetess Anna20. But at the end of the thirteenth century you can still find scenes of the Presentation in the Temple, as well where S. Joseph appears with an active part and we can cite, for example, an altarpiece (?) also from France (Burgundy) still from the final years of the 13th century or early 14th century, with scenes from the Childhood of Christ, belonging to the Museum of Saint Germaine of Auxerre, Yonne 21.

If you look at the large number of plaques, diptychs and triptychs sculpted in ivory, especially in the Paris region, between the 13th and 15th centuries - easily we notice that the scenes with the theme of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple represented in these objects of devotion generally consist of three characters (the Virgin, the Child and Simeon) and these are arranged around the altar, leaving no place for the presence of S. Joseph and the prophetess Anna (although there are exceptions ).

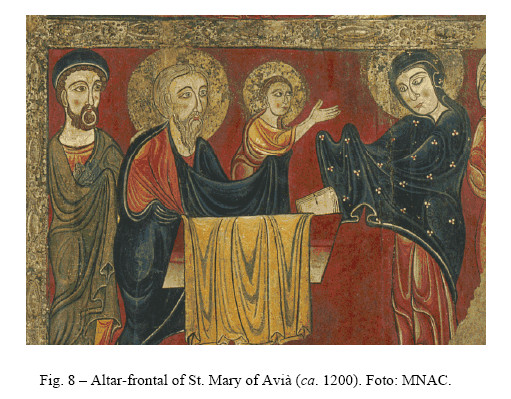

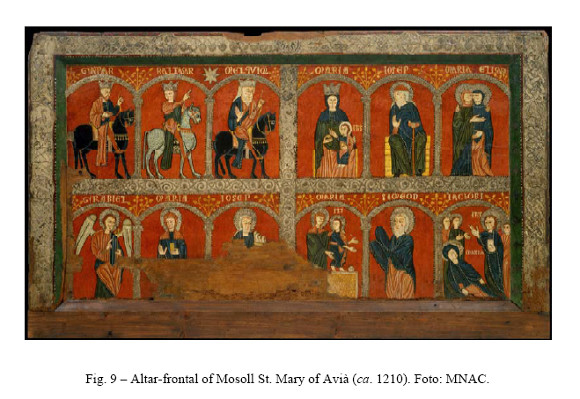

The closest artistic/iconographic historical record of the scene carved on the tomb/cenotaph of D. Rodrigo Sanches, in terms of time and geography, (especially given the relations that seem to have existed, early on, in this area of the peninsula, through the Mediterranean, having intensified in the fourteenth century)22, are in Catalan Romanesque paintings (Pyrenees), on wood, of which I refer three examples. In first place, the altar- frontal of Mare de Deu del Coll (inv. SEM 3), in which S. Joseph, who is behind the Virgin, holding the stick with one hand, holding up three doves on the same arm, and pointing with the other hand to the scene unfolding before him - the Virgin Mary, facing the altar helps to hold the baby Jesus that is received on the other side of the altar by the priest Simeon23. Slightly later, in terms of chronology, the altar- frontal of St. Mary of Avià (from the monastery with the same name, and now integrated into the collection of the National Art Museum of Catalonia - inv. MAC 15784), that Manuel Castiñeiras dated ca.120024, in the scene of the Presentation, the figure of S. Joseph also with the kippah to cover his hair, but without the rod, in a ¾ position facing the observer, placed immediately behind the priest holding the Child on the altar and hands him to the Virgin Mary, with prophetess Anna on her side.

It should be noted, also, that in this scene all characters have their hands covered by their robes (with the exception of the Child), as a sign of respect25. Finally, I must refer to the altar-frontal of Mosoll, ca. 121026, where, just as in the scene from the tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches, there are only the four main characters: St. Joseph, holding a basket with doves (four), not being possible to understand if originally he was holding the rod with the other hand. The figure bears no Jewish hat, but his head is haloed, as the remaining three figures of the scene. (Figs. 8 e 9

)

Although we cannot establish a direct link between these examples of Catalan Romanesque painting with the scene represented in the funerary monument of D. Rodrigo Sanches, it is undeniable the existence of well established typological/iconographic models, and its knowledge by the artists from the late 12th century and from the 13th century in the Iberian Peninsula, which they adapted them according to the material conditions of each work, the taste and the particulars of each customer, and that exceeded the boundaries of kingdoms that in those times, were more tenuous than you might assume from the outset, especially in what the movement of ideas and artistic models may concern.

Another peculiar element in this scene from the grave is that Simeon, the priest, is not represented with the head covered by a mitre, or with the hair uncovered, or yet with nimbus, such as is seen in the example of the altarpiece of Santa Maria de Mosoll, but having the head encircled by a tiara, something that the iconography of this elder also provides, but that is of greater rarity. At first glance, the fact that this tiara differs little or nothing from the crowns that we see on the other crowned heads of this side of the tomb chest, it would lead one to think it was the representation of a King. But, despite the fact that the priest does not receive, and hold, the Baby Jesus, having his arms and two hands covered by large mantle, this is the iconographic element necessary to leave doubts as to his identification.

In summary, and in accordance with the arguments presented above, it seems clear that the iconographic choice of the Adoration of the Magi and the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, the only, and sequential, scenes of the top of the tomb chest, in addition to symbolizing the beginning of life, had as main objectives to emphasize the recognition of the Messianic character and the royalty of Christ and a manifestation of the glory of God beyond the people of Israel.

2. The ω of the Redemption: the Calvary

The side of the other end of the tomb chest is decorated with the theme of Calvary, in other words, with the epilogue of the earthly life of Christ, but also the beginning of his Glorious Life. As already noted in the description of the scenes that decorate the end opposite the chest, the Calvary represented here also reveals some iconographic and even aesthetic options that make it different from all of the Calvaries reproduced in stone sculpture, among us, during the thirteenth century (in the case of some tombstones) and in the fourteenth century (in a significant number of tombs). (Fig. 10

)

The model of the cross is different from the most common types in representations of that time (12th and 13th centuries) - with arms ending in a straight cut27- and has four arms with fleur-de-lis endings. This allows to establish an immediate relationship with a model of processional crosses, made of metal with applied decorations, datable to the 13th century (mid and end of the century), present today in collections of national museums and some parish churches. These are characterized by their fleur-de-lis endings, decorated by applying quatrefoils (one in each arm of the cross) on which are normally fixed, in collar settings, five coloured glasses28. The figures of Christ that we can observe on these metal crosses, carved in ronde bosse, follow a somewhat standardized model in these years, which is characterized by the body slightly in serpentine and marked ribs by sequential and incised lines, denoting strong styling , with perizonium by the knees, both feet separately nailed to the cross, arms slightly bent and hands open and nailed to the cross, and the head slightly tilted to the right. The long and straight hair, falling on the shoulders are girded by the crown on the head, also fleur-de-lis styled, following the model propagated by the workshops of Limoges. Good examples of these crosses are some of which that are kept at the National Museum of Ancient Art (Lisbon), as is the inv. 62 met, and another from the National Museum of Machado de Castro (Coimbra) - inv. 6032 O 3, as well as in parish churches, distributed mainly in the region of Beiras, which shows that they should have had a lot of propagation during the Middle Ages29. It is clear, therefore, that the appreciation of these cross models in a territory which can be defined roughly between Coimbra and Minho, in other words, in the area of production and of destination of the tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches. (Fig. 11

)

It is very likely that this processional cross model was of knowledge of the characters involved in this artistic order, and the sculptor could even count on the presence of an identical model of existing processional cross on an altar in the church of Santa Cruz de Coimbra (or any Romanesque church of Coimbra), in which he may have been inspired. As we will see later on, it is also likely that the sculptor has taken the idea of the decorated quatrefoils fixed on referred crosses, to use them as decorative patterns, on the other side of the chest, since on Cross of the Calvary on the tomb, these decorations are naturally absent.

In the tomb, the figure of Christ, deceased and nailed to the cross, is the late-Romanesque Christ, that does not yet show the suffering caused by crucifixion, nor by the many inflicted wounds, but bares part of the body, showing the ribs to denote the leanness, and is only slightly inclined. He wears the perizonium, still long, typical in wooden and metal sculpture of the late 12th century and the first half of the 13th century, both of the Northern part of the peninsula and of the South of France and Burgundy30, as well as in the illuminations in many manuscripts. The head is not only crowned but haloed as well, without presence yet of the Crown of thorns31 or the Crown of rope, as seen in examples from this era and earlier. The face of Christ outlines an expression without suffering, without agony, with his eyes and mouth closed, quietly.

The cross of the Calvary represented in tomb differs from processional crosses mentioned before, due to the fact that the feet of Christ settle foot stool, and under this, but still integrated in the space of inferior vertical arm of cross, sitting with joined hands in a gesture of prayer is the little figure of Adam, bare, at the time of his resurrection, redeemed by the blood and death of Christ.

The presence of Adam at the foot of the cross is not a subject that appears in medieval tomb sculptures of the fourteenth century, the century in which Calvary is often represented on the tops of secular and religious tomb chests. Moreover, in the works already known and studied32, the subject does not appear once, being the Calvary on the tomb of Grijó not only the first, but the only one, inaugurating the theme of Adam risen at the foot of cross, since the work is datable to the years following 1245. Nor do we find the presence of Adam on the processional crosses mentioned, or on any other processional crosses of other types or origins, found presently in Portugal, dated prior to the fourteenth century. In the Illuminations in Portuguese manuscripts (or that exist in Portuguese monastic libraries), up to the middle of the thirteenth century there are no known examples of the Calvary with the presence of Adam. Even in a Bible dated ca.1250 (Coimbra, BGUC, safe 5), in the folio where the scenes of the Creation of the World are represented, ending with the Crucifixion of Christ, it is not safe to state that the shrouded figure that seems to rise from his coffin, placed the foot of the cross of Christ, is a representation of Adam, but eventually a canonical image of the Resurrection33. Therefore, this subject turns out to be more of a differentiating iconographic element of the tomb of Rodrigo Sanches, in addition to the other elements already observed in other scenes.

We must seek its precedence in much older peninsular works, and just remember the small figure of Adam risen at the foot of the cross of ivory ca. 1063, known as the Cross of D. Fernando and D. Sancha (offered by the royal couple to the Collegiate Church of San Isidoro de León, now in the National Archaeological Museum, Madrid (inv. 31325/I/FD00009)34, or another small figure represented on a Calvary, in the pages of a reliquary shaped diptych that is preserved in the Holy Chamber of Oviedo, donated by Bishop Gonzalo Menéndez (162-1175)35, or, in stone sculpture of the early twelfth century, in one of the no less famous reliefs that decorate the cloister of the Monastery of St. Domingo de Silos36, where, at the foot of the cross, one can see Adam out of the tomb, among other examples.

At the top of the composition, flanking the vertical arm of the cross, two angels heads are represented, one on each side, with their wings raised and summarily carved, being their faces too large and denoting a heavy loss of material (in the right) or with carvings and restorations (on the left), with robes - cut similar to almost all the male figures of this tomb. The angel on the right is swinging the censer (just as many other angels in scenes of Calvary) and the one on the left is holding a rectangular object. This object, seen from above, presents carving of what appears to be small spheres, and that could mean that it was um an antecedent of an incense boat carrying, as we shall see in funerary sculptures of the fourteenth century, also supported by angels, as exemplified by the tomb of Princess D. Isabel (ca.1330 – originally from the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha de Coimbra).

At the foot of the cross, and also beside it, is the Virgin, to the right, uncrowned, with a short veil that falls over her mantle, wearing a robe similar to those described for other images of Mary, but here a detail of great interest - the garment is fit to the waist by a belt with a buckle, the end of which hangs at the front of the figure, revealing the decoration with small metal applications, identical to the ones on the belt, which now we can see better on the tunic of the lying D. Rodrigo. This belt model, can be found in the French imaginary of 13th century (a good example of this is the statue of King Childebert of ca.1245 -1248 - Musée du Louvre, inv. N15001 - 93 ML, among other examples), that will only be found in Portuguese imaginary in fourteenth century, particularly in some works attributed to master Pero or his workshop. This is, therefore, another unique and precocious situation of this tomb.

The Virgin tilts her head slightly to the left, towards the cross, and joins her hands over her chest, as a sign of pain and introspection. On the left, St. John the Evangelist, who, just as Christ, also has his head haloed, holds with one hand the Gospel and joins the other hand to his face, showing another attitude of symbolic medieval gestural representing suffering. The faces of the two figures are very similar, and, as already mentioned for previous scenes, the sculptor uses the same facial patterns for most images. What is surprising here is that they both are assisted, each by a character without any iconographic attribute and represented only in part of their bodies (the one on the right already with severe material loss). By observing the figure that supports St. John the Evangelist, you can see that it is a male character (the type of hair), a situation that, if identical in the figure that cannot be seen presently in full, might, eventually represent Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, the two men responsible for the deposition of the cross and entombment of Christ. If so, this scene uses the same kind of artifice suggested in the childhood scenes of Christ: the somewhat mnemonic resort to using the junction of two, or more, moments in the history of Christ in one scene. In this scene, not only the crucifixion and death of Christ, but also the allusion to the descent from the cross is portrayed, a subject that in the years of the Romanesque was even more valued than the Crucifixion, as it is the beginning of Glorious Life of Christ.

3. The value of the royal blood

The entire decoration of the second long face of the Tomb chest is different in thematic (content), in the form and in intention, when compared with the other three sides. Besides, it's better preserved because it was covered for hundreds of years by mortar that glued it to the bottom wall of the arcosolium in the cloister of the monastery. Everything seems to contribute to give it a strange appearance, which, on a first impression, we tend to suspect of. It appears to be new. We're not used to viewing Romanesque sculpture (even late-Romanesque) with such sharp edges, with volumes little or nothing eroded, anyway, showing some discomfort even, for being devoid of religious figures to occupy the spaces in the midst of defining architectures.

In this case, and in a apparently careless way, in terms of symmetries, as we only observe coats of arms that point out, ostensibly, the lineage of royal bloodline, of the deceased (the shields of Old-Portugal), vegetal elements that "move" in such an unusual way, indented leaves of thick form, very round and bulky grapes, two great scallops without integration in the iconography of a St. James (the Pilgrim) or embedded in a heraldry of a shield, also comprising two quatrefoils integrating rosettes, which grow in the middle of a vegetal element totally idealized, as we see in some capitals, portal posts and other elements of architectural sculpture, especially in Italy, in the twelfth century, or in illuminated books. Finally, some unusual disharmony, but a composition full of vigour in its message, not markedly religious, but with the clear intention of exalting the lineage of D. Rodrigo Sanches, the same that was common to his sister, D. Constança Sanches, the consigner of this tomb (cenotaph) and the laudatory epitaph that before was accompanying him. (Fig. 12

)

This is not a strange decorative and themed option for one of the major faces of the tomb, especially if we consider that both the deceased knight, and the author of the order (D. Constança Sanches ?), were illegitimate sons of a king and, as we later find in other examples of medieval Portuguese tomb sculpture, that illegitimacy had also its proportionality in the emphasis given to the placement of heraldic elements (always from the paternal lineage) to decorate their tombs. And, if we take notice, the same shield with the arms of Portugal is represented on the pommel of the sword held by the recumbent, which makes obvious the intention not to leave unnoticed this lineage of royal bloodline. On the other hand, the time of completion of this funerary monument and the place where it was made or at least planned - the city of Coimbra, counted on, by these dates, at least one tomb (which is still integrated in Romanesque art of Coimbra), namely in the Cathedral, with the visible face decorated only with heraldic shields that identified the bishop buried there and also his support for the cause of the new king (has a shield of Old-Portugal and two with the arms of a bishop) . This is the tomb of D. Tiburcio, that Miguel Metelo de Seixas dated ca.124837. The same author, while observing the heraldry on the face of the Chest tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches (with two shields that have arms of Old-Portugal), nevertheless considering there idiosyncrasies in the less well distributed form of two shields through the field of sculpture, and not having the bezants engraved on the escutcheons (could possibly have been painted), sees no reason, from the heraldry present, to invalidate the completion of this work, in particular, of this face, during the thirteenth century38. Moreover, the lack of differentiation in the use of the arms of the royal family (unchanged) by the legitimate and illegitimate children of kings of the first dynasty has been amply demonstrated39.

The truth is that, apart from the outset the years more likely to medieval revivalism (especially the nineteenth century), in which there might have been a strange initiative to order the sculpture of a face, we could imagine, would never have been sculpted (and there is nothing to prove it) it is known that, since the first half of the seventeenth century, this has not happened because it has always been kept in arcosolium in the wall of the cloister, with that face completely hidden. What motives could have originated a similar initiative in the sixteenth century, for example? At the moment, I cannot find any. He is an illegitimate son of a king, who died several centuries before and whose material memory, in addition to the existing with his tomb and its epitaph, should not produce desires in any anonymous benefactor (or the monks of Grijó) to invest funds in the construction of a face of a tomb, if it were not carved, because the most natural thing to do would be to put it against a wall. Therefore, I assume that this face, with all its idiosyncrasies, but very curious elements of interest, is the contemporary of the remaining.

At the top of the face of the chest runs a rick-rack style frieze, parallels of which can be found in many works of the peninsular Romanesque, in various artistic techniques, such as in mural painting, and to give just one very expressive example, the frieze that divides scenes from the scenes from the nave of the Epistle of the Church of Santa Maria of Tahull (MNAC). In France, worth mentioning is a very good example, the frieze below the tympanum of the south portal of the old church of La Charité-sur-Loire (ca.1140), and other geographies, for example in illuminations, of which may be cited the frame illumination of the Virgin and Child and Donor Missal of Henry of Chichester (John Rylands University Library of Manchester, Ms. lat. 24), dated ca. 125040. Regarding the frieze of chained rows that delimits the bottom of the chest, we find an antecedent in the decoration of the western portal of the Old Cathedral of Coimbra41 that, among some patterns of the pilasters, presents a very similar typology to that of the bottom of the chest, as well as to another existing in the south portal of the church of S. Pedro de Rates.

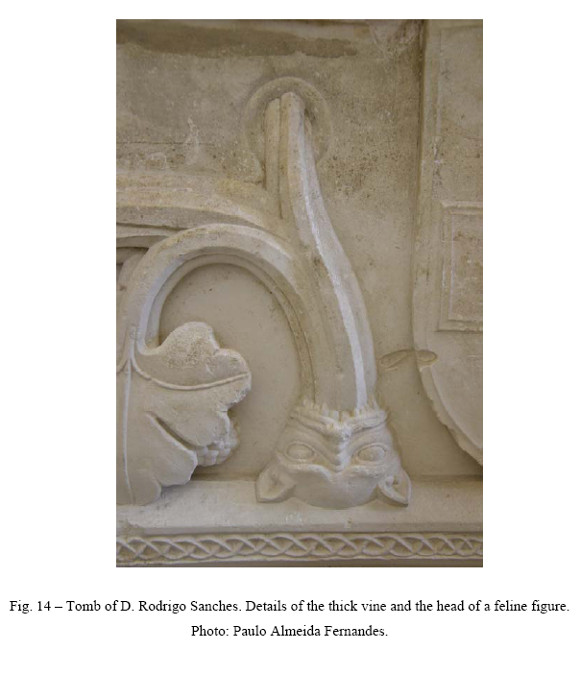

This face of the chest is also decorated with a thick vine stem that weaves "in and out" of the tombstone by fictitious circular holes. It is punctuated by leaves and grapes, cut and carved very bulky, a very common theme in medieval art for its clear allusion to Christ, and in particular the Eucharist. This think vine stem, striated, resembles the shape, and even the expressive force, of the stems, leaves and grapes that Benedetto Antelami carved in 1200 in the Baptistery of Parma, to represent the allegory of September. (Fig. 13

) Neither the artist was the same, nor the dates coincide, but this allusion allows realize that this kind of stems, leaves and fruits, carved in a way that was unknown in the Portuguese art hitherto, has other antecedents, of which this work of the noted Italian sculptor is a good example. The way the formal and iconographic models travelled, circulated and expanded in Europe at the time, is a field of study that remains open, but clearly affirmative as to its existence.

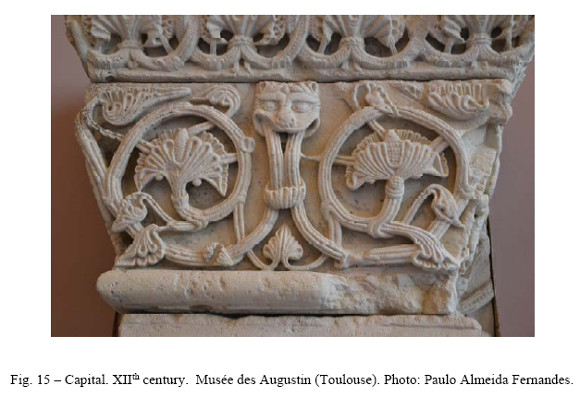

Leaves and pine cones carved in such a thick and protruding form, have other parallels in peninsular Romanesque art, such as the flowers that decorate the columns of the cloister of the church of San Andrés de Arroyo (Palencia), or a column of the arch of the chevet of the Church of Vallespinoso Aguilar, among many others. But the presence of weaving rods, that go out of the "limits" of the composition to then re-enter these limits, is also common in international and national Romanesque illuminations, including the example shown in page 2 of the Testamentum Veteris manuscript of Santa Cruz de Coimbra in the second half of the twelfth century (Santa Cruz 1)42. The way this tomb rod ends at the bottom of the field of the sculpture is also Romanesque, the head of a feline (or fantastic animal), that opens its mouth to let it in or out, is a topic that we often find in Anglo-Saxon Romanesque illuminations and that in Portugal, we find, for example, a folio dedicated to the creation of the world, in a Bible dated 1201-1250 (Lisbon, ANTT, 25 Basto - (CF 106)43. Perhaps inspired by the illumination are also examples of sculptural stems and fruits entering or leaving the mouths of very similar animals, for example the columns and friezes of ancient collegiate church of St. Peter of Coimbra (MNMC - inv . 9260 and 10454) , or a Romanesque capital that is saved in Museum of Toulouse - works of the 12th century. (Figs. 14 e 15

)

Surprising are the two big and bulky scallops that immediately refer to some kind link with the religious and/or pilgrimage to Santiago of Compostela, or a link to the Knights of Santiago. We were unable to ascertain, so far, of what is known of the biography of D. Rodrigo Sanches, if he integrated into the Santiaguist hosts, nor if he made any pilgrimage to Compostela, although it is known that his nephew and King, D. Sancho II was a pilgrim to this Sanctuary and, perhaps, to please this uncle from whom he received many blessings and positions, may have accompanied him in this journey of faith. Anyway, the Monastery of Grijó is one of the temples of the Portuguese Way of Santiago, which, by itself, could have motivated the mentor/iconologist of this tomb towards the placement of the two scallops, perhaps as a way of emphasizing this important condition of the grave site of D. Rodrigo Sanches. For now, the questions remain open. Anyway, being so unusual the presence of scallops as isolated elements to decorate tomb chests, we will just limit ourselves to appreciate them from the formal point of view and find the closest parallel in a scallop of a corbel of the chevet of the Church of Pisón Castrejón (Palencia), or, a little more distant, but more similar due to the volume of shells, reference to the scallops carved on a capital in the 12th century church of Charlieu.

At the opposite end of the face and also without great relationship with heraldic shields, are two quatrefoils, that perhaps, could be inspired by the decoration of the aforementioned processional crosses, or simply have been applied here because they constitute a decorative element that in those years was abundantly used in sculpture that decorated the facades of churches and cathedrals, already Gothic, such as Amiens or Burgos, for example. The decoration that we see in the space between the two quatrefoils is similar to what happens in the Romanesque illuminated manuscripts, including the one produced in monastic Portuguese scriptoria, being merely ornamental. This is what we can see and compare, as to the formal similarities with ornamentation (between the plant inspired motif and the complete idealization), of a manuscript of the ancient library of the Monastery of Alcobaça (Alc. 149, fl. 59V)44.

Another strange element, because of its apparent disconnection with the other elements, is a small figure of a lion, in profile and with fully heraldic features. Moreover, the presence of lions in this profile position, with one paw and tail raised (of heraldic nature) appears right in the pre-Romanesque art, but also in examples of Romanesque art, as are many lions within circles across the frame of the altarpiece in polychrome stucco from Ginestarre of Cardós (MNAC and MET). Simpler, and also more similar to the lion chest tomb, is the one that integrates a stem with foliage, in an illumination of fl. 136v of the manuscript "Santa Cruz 11"45.

Final notes46

The project that was the basis for the construction of the cenotaph of D. Rodrigo Sanches is owed, certainly, to the mind of a man holding erudite religious culture, but also chivalrous. The iconographic program sought an effective relationship between the religious scenes of the tomb: the eschatological idea of the beginning and the end of Christ's life as a form of redemption, making the parallel with the general idea, for all humans, of an earthly life that has beginning and end, but that due to the Resurrection of Christ, allows salvation after the final judgment - an idea which is underlined by the scene of Christ in Majesty (Christ Risen and Glorified, that overshadows the World), accompanied by the apostles.

It is, therefore, also a message that aims to emphasize the glory of Christ, and cannot fail to remind us of the iconographic program of the aforementioned tympanum of the ancient portal of the church of La Charité-sur-Loire, where under the Transfiguration scene, the only two scenes of the frieze below are the Epiphany and the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple47. Despite the difference between the Transfiguration of Christ (in the tympanum) and Christ among the Apostles (in the tomb), and both scenes of the iconography of Christ in Glory, the coincidence of choosing these two specific themes of the Childhood of Christ come link these works by ideological intentions (or part thereof).

On the other hand, and in a subtle way, the program did not fail to emphasize the moments of Christ's life in which his royal blood stands out (in the genealogical line of David), a situation which cannot fail to connect with the appreciation that we find in this cenotaph for the royal blood of D. Rodrigo Sanches, claimed not only by the sword of the recumbent (where was also carved a small coat with the arms of Portugal), but with great emphasis on the face where the two shields with the royal arms can be seen. The relationship between the representation of the recumbent and the figures of angels that accompany him (including those carrying the soul of the deceased to heaven (elevatio animae), and the ancient epitaph that identified and praised the deceased, has been examined in a recent study and interconnects perfectly with the foregoing48. This is why an erudite iconographic program, which preserves legacy of Romanesque themes of eleventh and twelfth centuries, but which is also sensitive to a number of innovations based on a new religious sensibility, the result of many religious and social changes that occurred in Europe until the mid- thirteenth century. The sculptor responsible for this work done in the soft limestone Coimbra, was also not numb to the new religious sensibility, he who was probably a connoisseur of painting and sculpture held in other peninsular kingdoms (particularly in Northern Spain - Castilla-Leon, but also Catalonia), as well as the possibility of having access to sheets of drawings or manuscript illuminations kept in the armarium in the Monastery of Santa Cruz in Coimbra, and that reproduced without remarkable plastic and aesthetic quality, but responding perfectly to the messages intended by the contractor and/or iconologist through iconography.

Referências bibliográficas:

AFONSO, Luís Urbano – O Ser e o Tempo. As Idades do Homem no Gótico Português. Lisboa: Caleidoscópio, 2003. ISBN- 972-8801-08-4 [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Carlos Alberto Ferreira de; BARROCA, Mário Jorge – História da Arte em Portugal. O Gótico. Lisboa: Presença, 2002. ISBN: 972-23-2841-7 [ Links ]

BANGO TORVISO, Isidro G. dir. –Maravillas de la España medieval. Tesoro Sagrado y Monarquía. Vol. I. León: Junta de Castilla y León/ Caja de España, 2001. ISBN: 84-877739-97-0 [ Links ]

BARROCA, Mário Jorge – Epigrafia Medieval Portuguesa (862-1422). Corpus Epigráfico Medieval Português, Vol. II, Tome I. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/ Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, 2000. ISBN – 972-31-0869-0 [ Links ]

BARROCA, Mário Jorge – Jacente de D. Rodrigo Sanches. In BARROCA, Mário Jorge; MONTEIRO, João Gouveia (coord.) – Pera Guerrejar. Armamento Medieval no Espaço Português. Palmela: Câmara Municipal, 2000. ISBN: 972-8497-10-5. p. 83. [ Links ]

CASTIÑEIRAS, Manuel – La pintura sobre tabla. In CASTIÑEIRAS, Manuel; DURAN-PORTA, Joan – El Románico en las Colecciones del MNAC. Barcelona: MNAC, 2008. ISBN: 978-84-8043-195-9. pp. 89-116. [ Links ]

Cook, Walter William Spencer; Gudiol, José – Pintura e imaginería românicas. Ars Hispaniae. História Universal del Arte Hispânico. Vol. 6. Madrid: Plus Ultra, 1950. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Carla Varela – Construção imagética do Herói-Mártir. O caso de D. Rodrigo Sanches. in ARTIS, Revista do Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa. Lisboa. ISSN:2182-8571. Vol. 9/10 (2011), pp. 109-124. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Carla Varela – PATHOS– the bodies of Christ on the Cross. Rhetoric of suffering in wooden sculpture found in Portugal, twelfth-fourteenth centuries. A few examples". In RIHA Journal l0078 (28 November 2013): http://www.riha-journal.org/articles/2013/2013-oct-dec/fernandes-christ [ Links ]

FRANCO, Anísio; PENALVA, Luísa – Cruz processional. in dOREY, Maria Leonor Borges de Sousa (coord.) – Inventário do Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Colecção de Metais. Cruzes Processionais – Séculos XII-XV. Lisboa: Ministério da Cultura/ Instituto Português de Museus, 2003. ISBN: 972-776-062-7. p. 71. [ Links ]

LAVAURE, Annik – LImage de Joseph au Moyen Âge. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013. ISBN : 978-2-7535-2195-7 [ Links ]

LE POGAM, Pierre-Yves – Les Retables à lépoque romane, and Les Retables au XIIIe siècle. in POGAM, Pierre-Yves (dir.) – Les Primieres Retables (XIIe – début du XVe Siècle). Une Mise en Cene du Sacré. (Exhibition catalogue). Paris: Musée du Louvre Éditions, 2009. ISBN 978-2-35031-238-5. pp. 21-49 and 51-83. [ Links ]

MALDONADO, Margarita Ruiz – Escultura Funeraria de siglo XIII: Los Sepulcros de los Lopez de Haro. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 1996. ISBN: 8474819822 [ Links ]

MIRANDA, Maria Adelaide – A Iluminura Românica em Santa Cruz de Coimbra e Santa Maria de Alcobaça. Subsídios para o estudo da iluminura em Portugal. 2 vols. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade de Lisboa, 1996, (Ph.D. Thesis). [ Links ]

MIRANDA, Maria Adelaide (coord.) – A Iluminura em Portugal. Identidade e Influência (do séc. X ao XV). (Exhibition catalogue). Lisboa: Ministério da Cultura/ Biblioteca Nacional, 1999. ISBN: 972-565-266-5. [ Links ]

MORGAN, Nigel J. – 108. Missal of Henry of Chichester. in Alexander, Jonathan; Binski, Paul (ed.) – Age of Chivalry. Arte in Plantagenet England 1200-1400. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1987, p. 235. [ Links ]

PRÉVILLE, Agnés de; boespflug, François – La gloire du Christ transfiguré. Le Monde de la Bible. Paris. ISSN: 0154-9049. Vol. 148 (2003), pp. 66-67. [ Links ]

Ramôa, Joana – Christus Patiens. Representações do Calvário na Escultura Tumular Medieval Portuguesa (século XIV). Lisboa: Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade de Lisboa, 2008. ISBN: 978-989-95291-2-0 [ Links ]

REAL, Manuel Luís – A Arte Românica de Coimbra (Novos Dados – Novas Hipóteses), 2 vols. Porto: Faculdade de Letras do Porto, 1974. (BA thesis). [ Links ]

REAL, Manuel Luís – Escultura tumular, unprecedented print (copied). [ Links ]

REAL, Manuel Luís, 60. Calvário e Investidura de Santo Ildefonso. Elemento do retábulo da Mártir Santa Comba. in EUSÉBIO, Maria de Fátima; SOALHEIRO, João (coord.) – Arte, Poder e Religião nos Tempos Medievais. A Identidade de Portugal em Construção. (Exhibition catalogue). Viseu: Câmara Municipal de Viseu, 2009, pp. 244-246. ISBN: 978-972-8215-26-2 [ Links ]

Réau, Louis – Iconografia del Arte Cristiano. Tome 1/ vol. 2. Barcelona: Ediciones del Serbal, 1996. [reed. of Iconografie de lArt Chrétien, F.U.F., 1957]. ISBN: 84-7628-189-7 [ Links ]

SeixaS, Miguel Metelo de – El simbolismo del territorio en la heráldica regia portuguesa. En torno a las armas del Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil y Algarves. in Emblemata. Zaragoza, ISSN 1137 – 1056. Vol. 16 (2010), pp. 285-329 and 290-296. [ Links ]

SEIXAS, Miguel Metelo de; GALVÃO-TELES, João Bernardo – Sousas Chichorros e Sousas de Arronches: um enigma heráldico. in ROSAS, Maria de Lurdes; SEIXAS, Miguel Metelo de (ed.) – Estudos de Heráldica Medieval. Lisboa: Instituto de Estudos Medievais, FCSH-UNL, 2012. ISBN: 978-989-97066-5-1. pp. 411-445. [ Links ]

Teixeira, Francisco Manuel de Almeida Correia – Arquitectura Monástica e Conventual Feminina em Portugal, nos séculos XIII a XIV. Faro: Universidade do Algarve/ Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, 2007. (Ph.D Thesis) [ Links ]

TUDOR-CRAIG, Pamela – Panel Painting. In Alexander, Jonathan; Binski, Paul (ed.) – Age of Chivalry. Arte in Plantagenet England 1200-1400. (Exhibition catalogue). London, Royal Academy of Arts, 1987, p. 132. [ Links ]

TRULLÉN, Josep M. (dir.) – Museu Episcopal de Vic. Guia de las Colecciones.Vic: Obispado de Vic/Ayuntamiento de Vic/ Generalitat de Catalunya, 2007. ISBN: 978-84-611-6318-2. [ Links ]

WIRTH, Jean – LImage à LÉpoque Romane, Paris: Cerf, 1999. ISBN : 978-2-0686-8 [ Links ]

COMO CITAR ESTE ARTIGO

Referência electrónica:

FERNANDES, Carla Varela – The Tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches: the rediscovery of an iconographic program. Medievalista [Em linha]. Nº 16 (Julho - Dezembro 2014). [Consultado dd.mm.aaaa]. Disponível em http://www2.fcsh.unl.pt/iem/medievalista/MEDIEVALISTA16\ [ Links ]

Data recepção do artigo: 18.Novembro.2013

Data aceitação do artigo: 8.Maio.2014

Notas

1 Date of August 23 of that year the issue of the opening Notice of the tomb (the remains were removed and stored in a safe) and its removal from the wall on the Gospel side of the chancel of the temple to the cloister (with a known copy, drawn up at the time of a second opening of the vault, July 1726) where an arcosolium awaited it. About this news and the different authors who they refer attention to BARROCA, Mário Jorge – Epigrafia Medieval Portuguesa (862-1422). Corpus Epigráfico Medieval Português, Vol. II, Tomo I. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/ Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, 2000, ISBN 972-31-0869-0. p. 819.

2 The measure is due to the initiative of the current priest of Grijó, Father António Coelho, having been recently kept in a small dependence of the cloister. The news of this event was shared with me by Manuel Luís Real, whom I thank, as well as for monitoring the visits we made to this monastery, a few days later (and also for the always fruitful exchange of ideas).

3 SANTA MARIA, Fr. Nicolau de – Chronica da Ordem dos Cónegos Regrantes do Patriarcha Santo Agostinho. 2 vols. Lisboa. 1668, 1.st Part. p. 284 quoted by BARROCA, Mário Jorge – op. cit., 2000, p. 814.

4 Opposed to the one that was always visible and that presents figures of apostles inserted in a round arcade with decorated capitals, having at the center the Maiestas domini.

5 See FERNANDES, Carla Varela – Construção imagética do herói-mártir. O caso de D. Rodrigo Sanches. in ARTIS, Revista do Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa. Lisboa. ISSN 2182-8571. Vol. 9/10 (2011), pp. 109-124. Only the reading/interpretation of the last figure of the left extremity of the side of the apostles will be reassessed in the next chapter, since, and being novelty in the Portuguese tomb sculpture, we know now that this figure is connected with the scene that unfolds in the next side, creating a dynamic of continuity between faces of the chest.

6 See the pictures and the studies on the two mentioned altarpieces at LE POGAM, Pierre-Yves – Les retables à l'epoque romane, and Les retables au XIIIe siècle. in LE POGAM, Pierre-Yves (dir.) - Les Primieres retables (XIIe - début du Siècle XVe). Une Mise en Cene du Sacré. (Exh. Cat.). Paris: Musée du Louvre Éditions, 2009. ISBN 978-2-35031-238-5. pp. 21-49 and 51-83.

7 Good examples of these cases are, the Adoration of the Magi painted on a dome of Santa Maria de Tahüll, transferred to the National Art Museum of Catalonia, or the front of the Altar of Sant Vicenç de Espinelves, ca. 1187, the Episcopal Museum of Vic (inv. MEV 7), or the front of Altar Mosoll, from the first third of the thirteenth century, from the church of Santa Maria de Mosoll (Low Cerdaña, Catalonia), in exhibition at the National Museum of Catalan Art (inv. 15788).

8 In 2011, and without even glimpse the existence of religious iconography on the face of the chest which corresponds to the position of the head of the deceased, Carla Varela Fernandes hypothesized that 14th figure on the frieze of the apostles, being crowned and did not having a defined iconographic attribute, could possibly be a representation of King Sancho I, father of D. Rodrigo (FERNANDES, Carla Varela – op. cit., 120-123) - the path of hypotheses already envisaged by Luis Manuel Real ("tomb sculpture" printed novel (copied), and Mário Jorge Barroca, who put forward that it was D. Afonso III (see ALMEIDA , Carlos Alberto Ferreira de; BARROCA, Mário Jorge – História de Arte em Portugal, O Gótico, Lisboa: Presença, 2002. ISBN 972-23-2841-7, p. 218) - in the medieval condition of anointed king, son and earthly arm of the power of God, since, also, no attribute allowed the hypothesis of it being the representation of David or Solomon. Given that, today one can see the once hidden face, these assumptions make no sense and open up the field to the new interpretation, this being a case, like others, that the artwork can always bring new data and provide new interpretations.

9 Already described in BARROCA, Mário Jorge – Jacente de D. Rodrigo Sanches. In BARROCA, Mário Jorge; MONTEIRO, João Gouveia (coord.) – Pera Guerrejar. Armamento Medieval no Espaço Português. Palmela: Câmara Municipal, 2000. ISBN 972-8497-10-5. p. 83.

10 As can be seen in the clothing of the group of kings sculpted in one of the corners of the cloister of the Cathedral of Burgos, or even in pictures of King Alfonso X (?) of the group of elected at the scene of the Final Judgment of the axial Portal of the Cathedral of León, and in the same cathedral, the representation of Don Martín "El Zamorano" (1242) in the face of his grave, all works of the thirteenth century.

1111 On this subject, through the reading of different works, see, AFONSO, Luís Urbano – O Ser e o Tempo. As Idades do Homem no Gótico Português. Lisboa: Caleidoscópio, 2003. ISBN 972-8801-08-4

12 See WIRTH, Jean – LImage à LÉpoque Romane. Paris: Cerf, 1999. ISBN 978-2-204-06086-8. pp. 57-58.

13 The genealogic issue of S. Joseph and the Virgin Mary was no longer an interesting debate in the twelfth century and the following centuries, being the main figures the famous Suger, abbot of Saint Denis, which, in the Tree of Jesse on a stained glass window in its basilica, replaced the figure of S. Joseph by the Virgin, thus altering the lineage of both characters (see the study of LAVAURE, Annik - Image of Joseph au Moyen Âge. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013. ISBN 978-2-7535-2195-7. pp. 27-60).

14 The same iconographic attribute found, eg, in the hands of the Virgin and Child in Majesty, painted in the center of the altar front of Mare de Deu del Coll, work of the last quarter of the twelfth century, on display at the Episcopal Museum of Vic (inv. MEV 3).

15 That resembles, in part, the physiognomic modeling of older recumbent effigies (thirteenth century) of the pantheon of the Monastery of San Zoilo, in Carrión de los Condes.

16 Note that these six-pointed stars, in a circular field, also appear on the face of the tomb chest which opposes the face of the apostolate, as if holding a decorative function, which we can infer from the spaces they occupy, as well as on the tunic (pelisse) on the recumbent effigy of D. Rodrigo, without being able to say it is a standard element of the fabric of this garment, but only one isolated element that the artist put there without having an obvious explanation, at the moment.

17 Note that one of capitals of the cloister of the monastery of Santa Maria de Celas (Coimbra) is devoted to the theme of the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, a more complete composition in characters and props and dated critically, in a recent study (TEIXEIRA, Francisco Manuel de Almeida Correia - Arquitectura Monástica e Conventual Feminina em Portugal, nos séculos XIII a XIV, Faro: Universidade do Algarve/ Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, 2007, (Ph.D Thesis). pp. 196-198), as the work of the second quarter of the fourteenth century, making it a much later work than the tomb of D. Rodrigo Sanches.

18 Réau, Louis – Iconografia del Arte Cristiano. Tomo 1/ vol. 2. Barcelona: Ediciones del Serbal, 1996, [reed. of Iconografie de lArt Chrétien, F.U.F., 1957]. ISBN 84-7628-189-7. pp. 272-274.

19 Ibidem, p. 275.

20 An example of the increased role of the prophetess is also in the works of the thirteenth century, one of the scenes that compose a stone altarpiece carved in relief, originating from the workshops of the Île-de-France, and which is now in the parish church of Saint-Sulpice Maisoncelles-en-Brie (Seine et Marne), dating from the third quarter of the thirteenth century (BERNET, Damien, 17 a, b - Scènes de la vie de la Vierge et de l'Enfance du Christ. in LE Pogam, Pierre-Yves (dir.) – op. cit., p. 81-83), or, already in the fourteenth century, the example of a scene of the Presentation at the temple, in an ivory diptych of French origin, where the Virgin is preceded by the prophetess Anna holding the basket of doves of the offering, which now belongs to the collections of the Metropolitan Museum, NY (inv. sf17-190-214s5).

21 VIVET-PECLET – 5. Scènes de lEnfance deu Christ, en deux registres . in LE POGAM, Pierre-Yves (dir.) – op. cit., 2009, p. 199.

22 Issues presented by Carla Varela Fernandes to the International Colloquium on Medieval Europe in Motion. The Circulation of Artists, Images, Patterns and Ideas from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Coast (12th-15th Centuries) held in Lisbon from 18 to 20 April 2013 in a presentation entitled "Transfer and artistic movement in Europe between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries: agents, models and techniques. The case of Portuguese sculpture from the late twelfth century to the end of the fourteenth century. Examples".

23 TRULLÉN, Josep M. – The altar-frontal of la Mare de Déu del Coll. In TRULLÉN, Josep M. (dir.) – Museu Episcopal de Vic. Guia de las Colecciones.Vic: Obispado de Vic/Ayuntamiento de Vic/ Generalitat de Catalunya, 2007, p. 99.

24 CASTIÑEIRAS, Manuel – La pintura sobre tabla. In CASTIÑEIRAS, Manuel; DURAN-PORTA, Joan (coord.) – El Románico en las Colecciones del MNAC. Barcelona: MNAC, 2008, ISBN 978-84-8043-195-9. p. 112.

25 This oriental rite can also be found in scenes depicting the Baptism of Christ, where angels also have their hands covered as a sign of respect.

26 CASTIÑEIRAS, Manuel – op. cit., 2008, p. 120.

27 Of which there are many examples in Portugal that have reached our days, in metal processional crosses, wooden crosses, or even representations of illuminated books of Portuguese scriptoria, and the cross is an excellent example that we observe in Calvário de Saltério de Santa Cruz de Coimbra, from 1179 (Porto, BPMP, Sta. Cruz 27 / Ms. 92), or in the Crucifix represented in fl. 30 of Missal festivo e votivo, dated 1201-1225 (Porto, BPMP, Sta. Cruz 40 / Ms. 53 On these two illuminations see MIRANDA, Adelaide - 031. [Missal festivo e votivo] and PEIXEIRO, Horácio - 035 [Saltério]. In Miranda, Maria Adelaide (coord.) – A Iluminura em Portugal. Identidade e Influência (do séc. X ao XV). Exh. Cat. Lisboa: Biblioteca Nacional, 1999. ISBN 972-565-266-5. pp. 210-211 e 218-219.

28 See FRANCO, Anísio; PENALVA, Luísa – Processional Cross. In DOREY, Maria Leonor Borges de Sousa (coord.) – Inventário do Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Colecção de Metais. Cruzes Processionais – Séculos XII-XV. Lisboa: Ministério da Cultura/ Instituto Português de Museus, 2003. ISBN 972-776-062-7. p. 71.

29 Ibidem, pp. 71-72.

30 About these stylistic questions and the presence in the Portuguese Romanesque art (compared to other western countries) see FERNANDES, Carla Varela – PATHOS– the bodies of Christ on the Cross. Rhetoric of suffering in wooden sculpture found in Portugal twelfth-fourteenth centuries. A few examples," RIHA Journal l0078 (28 November 2013): http://www.riha-journal.org/articles/2013/2013-oct-dec/fernandes-christ

31 Some later representations, but archaic, keep the two crowns, as is the case of the Crucified Christ that we see altar-frontal, of stone, critically dated from the late thirteenth century or early fourteenth century, and founded the ancient shrine of Santa Comba (near Coimbra), now integrated into the National Museum of Machado de Castro - inv. 946 E 13 (REAL, Manuel Luís – 60. Calvário e Investidura de Santo Ildefonso. Elemento do retábulo da Mártir Santa Comba. In EUSÉBIO, Maria de Fátima and SOALHEIRO, João (coord.) – Arte, Poder e Religião nos Tempos Medievais. A Identidade de Portugal em Construção. Exh. Cat. Viseu: Câmara Municipal de Viseu, 2009. ISBN 978-972-8215-26-2. pp. 244-246.

32 Ramôa, Joana – Christus Patiens. Representações do Calvário na Escultura Tumular Medieval Portuguesa (século XIV). Lisboa: Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade de Lisboa, 2008. ISBN: 978-989-95291-2-0

33 See MIRANDA, Maria Adelaide (coord.) – op. cit., 1999, pp. 260-261.

34 On this work see FERNÁNDEZ SOMOZA, Glória – 88. Cruz de Fernando I y Sancha. In BANGO TORVISO, Isidro G. (dir.) –Maravillas de la España medieval. Tesoro Sagrado y monarquía. Vol. I. León: Junta de Castilla y León/ Caja de España, 2001, pp. 230-231 (with another bibliography).

35 Cook, Walter William Spencer

; Gudiol, José, co-aut. – Pintura e imaginería românicas. Ars Hispaniae. História Universal del Arte Hispânico, vol. 6, Madrid: Plus Ultra, 1950, p. 293.36 About the reliefs of the cloister of Silos see VALDEZ DEL ALAMO, Elizabeth – Palace of the Mind: The Cloister of Silos and Spanish Sculpture of the Twelfth Century. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012.

37 SeixaS, Miguel Metelo de – El simbolismo del territorio en la heráldica regia portuguesa. En torno a las armas del Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil y Algarves. in Emblemata. Zaragoza.ISSN 1137 – 1056. Vol. 16 (2010), pp. 285-329 e 290-296.

38 To whom I thank heartily for having accepted the challenge to observe, exchange views and give your authoritative opinion on the presence of the two shields with the arms of "Portugal-Old": despite the aforementioned asymmetry and strange environment, keeps the escutcheons lying, such as they stayed up to the sixteenth century, and the fact that today you cannot see the bezants in these escutcheons (could have been originally painted), anything invalidates the originality of this sculptural achievement, ruling out a revivalist reconstruction between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, since the tomb was "stuck" to the arcosolium since the seventeenth century.

39 SEIXAS, Miguel Metelo; GALVÃO-TELES, João Bernardo – Sousas Chichorros e Sousas de Arronches: um enigma heráldico. in ROSAS, Maria de Lurdes; SEIXAS, Miguel Metelo de (eds.) – Estudos de Heráldica Medieval. Lisboa: Instituto de Estudos Medievais, FCSH-UNL, 2012. ISBN 978-989-97066-5-1. pp. 411-445.

40 See MORGAN, Nigel J. – 108. Missal of Henry of Chichester. In Alexander, Jonathan; Binski, Paul (eds.) – op. cit., p. 235.

41 REAL, Manuel Luís – A Arte Românica de Coimbra (Novos Dados – Novas Hipóteses). 2 vols. Porto: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, 1974. Fig. 339 E. (BA Thesis).

42 In the identification of MIRANDA, Maria Adelaide – A Iluminura Românica em Santa Cruz de Coimbra e Santa Maria de Alcobaça. Subsídios para o estudo da iluminura em Portugal. Vol. II. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade de Lisboa, 1996, Fig. 40. (Ph.D Thesis).

43 Published in Miranda, Maria Adelaide (coord.) – op. cit., 1999, 246-247, or in the 1st volume of a Bible of Alcobaça (Alc. 427, fl. 154), reproduced in MIRANDA, Maria Adelaide – op. cit., 1996, vol. II, Fig. 87.

44 Given to the press by MIRANDA, Maria Adelaide – op. cit., 1996. Vol. I. p.127 and vol. II: Fig. 8, among other examples.

45 Ibidem, vol. II, Fig. 104.

46 I would like to thank Susan Costa for her quickness, professionalism and constant availability in translating this paper.

47 PRÉVILLE, Agnés de; boespflug, François co-aut.– La gloire du Christ transfiguré. in Le Monde de la Bible. Paris. Vol. 148 (2003), pp. 66-67.

48 As already pointed out in the mentioned study of FERNANDES, Carla Varela – op. cit. (2011), which also creates a relation between the recumbent effigy, and the amazing amount of angels that accompany him on the lid of the chest tomb (no other tomb of the thirteenth century shows this quantity of angelic figures, arranged in such diverse positions and movements), with the text of the laudatory epitaph, where the knight, worthy of all the virtues, was compared to the hero Roland. Now, and in the possession of knowledge about the iconography of the remaining sides of the ark, even more the laudatory emphasis of the virtues, of heroism, and also the royal lineage is evident in the intention of the principal and/or iconologist of this the work.