Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Medievalista

versão On-line ISSN 1646-740X

Medievalista no.29 Lisboa jan. 2021

https://doi.org/10.4000/medievalista.3896

DOSSIER

Chased by a unicorn. re-studying and de-coding the parable of the futile life in the novel Barlaam and Josaphat (medieval greek version)

Perseguido por um unicórnio. re-vendo e des-codificando a parábola da vida fútil no romance Barlaão e Josafat (versão grega medieval)

Georgios Orfanidis1

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5047-1044

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5047-1044

1Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (A.U.Th.), Faculty of Theology, Department of Theology, 541 24, Thessaloniki, Greece, georgioso@theo.auth.gr

ABSTRACT

The parable of the Futile Life, which is an excerpt of the medieval, multilingual novel Barlaam and Josaphat, conceals a unique interpretative approach, in terms of symbolism, of an ancient and intercultural mythological symbol, that of the unicorn. From a first examination of the cultural environment - textual and iconographical - of the unicorn’s appearance, it would seem that the symbolic substance of this animal motif was imbued with the notions of the high virtues of the Christian ideological system (e.g. virginity, purity, salvation). However, the parabolic narrative of the Futile Life reveals another aspect. This is the aspect of the inward cruel power that drives a man to the wrong choice, preventing him from finding the proper spiritual way out to save himself after his physical death in the vanity world in which he lives transiently. Probably, the beauty of a unicorn now symbolizes something not so pure. Indeed, the story of the Futile Life is transformed into one of the most common iconographic themes in monumental Christian painting, and, at the same time, it raises reasonable concerns while seeking adequate explanations. So, through a list of relevant examples of monumental and miniature art, we will look for the beginnings of the two aspects of this ancient symbol, with an emphasis on the parable under examination, offering a new perspective on the semiotic analysis of Antiquity during the Middle Ages

Keywords: Barlaam; Josaphat; Futile Life; Fantastic Animals; Unicorn

RESUMO

A parábola da Vida Fútil, que constitui uma parte do romance medieval multilíngue Barlaão e Josafat, esconde uma abordagem interpretativa única, em termos de simbolismo, de um símbolo mitológico antigo e intercultural, o do unicórnio. Um primeiro exame do ambiente cultural - textual e iconográfico - da aparência do unicórnio dá a entender que a substância simbólica deste motivo animal terá sido imbuída de noções decorrentes das altas virtudes do sistema ideológico cristão (por exemplo, virgindade, pureza e salvação). No entanto, a narrativa parabólica da Vida Fútil revela outro aspecto. Trata-se do poder interior cruel que leva o homem à escolha errada, impedindo-o de encontrar o caminho espiritual adequado para salvar-se após a sua morte física no mundo de vaidade em que vive temporariamente. Provavelmente, a beleza do unicórnio simboliza agora algo que já não é tão puro. Na verdade, a história da Vida Fútil tornou-se num dos temas iconográficos mais comuns da pintura cristã monumental, incluindo a presença do unicórnio, o que levanta, ao mesmo tempo, preocupações razoáveis e a necessidade de explicações adequadas. Assim, através de uma lista de exemplos relevantes de arte monumental e em miniatura, procuraremos identificar o início dos dois aspectos deste antigo símbolo, com ênfase para a parábola estudada, oferecendo uma nova perspetiva sobre a análise semiótica da Antiguidade durante a Idade Média.

Palavras-chave: Barlaão; Josafat; Vida Fútil; Animais Fantásticos; Unicórnio

1. Barlaam and Josaphat: A Christian tale

Barlaam and Josaphat (Latin: Barlamus et Iosaphatus), who were Early worshiped as Christian saints, are the protagonists of the homonymous hagiographic novel, which was very popular in the Medieval Byzantine. The novel was probably inspired by the biography of the world-renowned religious figure of Siddhārtha Gautama (Buddha), titled Life of Bodhisattva[1]

The plot of the story unfolds through a series of varied events, essentially of a philosophical and didactic nature, on the second level of reading. More specifically, a king in India (the “Inner Land” according to the Ethiopians) was casting out the Christian community who lived in his realm. When the astrologers predicted that the king’s son, Josaphat, would someday abandon his family's faith and turn to the Christian worldview and ideology, he imprisoned the young prince, who, despite the harsh conditions which he found himself in, met the hermit-saint Barlaam and formally embraced the Christian ideals. However, after much pressure and a great personal battle with many, both external and internal (psychological) trials, the king accepted the Christian religion himself, thus allowing Josaphat to claim succession to the throne. The repentant king abandoned his royal office and moved to the desert, devoting himself totally to the new God. In the end, Josaphat himself relinquished his previous way of existence and followed the underprivileged life of isolation alongside his mentor, Barlaam. Thereafter, Josaphat became an advocate of the Christian faith as a missionary in the geographical area covering his former kingdom which he had been expected before to rule

In fact, the personal tale of Bodhisattva has led to the flourishing of many publications/versions in several languages spoken generally during the first millennium A.D. across the Indo-Persian backdrop. This fabula has been derived from a text of Mahāyāna Buddhism in the Sanskrit language dating from the 2nd to the 4th century AD via a Manichaean version, which later found fertile ground in the Arabic-speaking Muslim culture, centering around the city of Baghdad, in the form of a widespread literary text dating back to the 8th century, entitled Kitāb Bilawhar wa-Yūdāsaf/Būd̲h̲āsaf (The Book of Bilawhar and Yūdāsaf/Būd̲h̲āsaf)[2]

It was translated into Old Georgian in the 9th or 10th century with the title Balahvaris Sibrdzne (Balavariani) (meaning Wisdom of Balahvari), and it resulted in the creation of the Christianized version of the original text[3]. This Christian version was then translated into Greek in the 10th or 11th century, not by the erudite John of Damascus (675/676-749), as it was previously believed[4], but by the son of the Georgian nobleman and thereafter monk Ioane Varaz-vache Chordvaneli, the nephew of the great Tornike Eristavi, Euthymius the Hagiorite, Athonite or Iberian (955-1028), Abbot of the Iviron Monastery of Mount Athos, just before he died in an accident while visiting Constantinople in 1028. It was subsequently translated into Latin in the mid-11th century[5]. The Greek adaptation was translated into Latin during the mid-11th century (1048), being published in Western Europe under the name Barlamus et Iosaphatus. This version in Latin facilitated the entry of this multi-influenced culturally legendary story in the Romance languages (e.g. by Otto II of Freising, Laubacher Barlaam, c. 1220; Rudolf von Ems, Barlaam und Josaphat, 13th century; Jacques de Voragine, La Légende Dorée, 13th century)[6]

2. The futile life

One of the most interesting parables of the novel, on the one hand, due to the plethora of ancient symbols it contains (e.g. The Tree of Life and beasts from the ancient mythological tradition of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East), and, on the other hand, because of the particular hortatory content resulting from the semiotic and pragmatic interpretation of the above-mentioned symbols, is the didactic narrative titled The Sweetness of the World (medieval Greek: Τοῦ Κόσμου ἡ Γλυκύτης), or more commonly, The Futile Life (medieval Greek: Ὁ Μάταιος Βίος)[7]

Τhe Armenian art historian Sirarpie Der Nersessian, who studied this story in detail reports in her book L' illustration du roman de Barlaam et Joasaph (1937) that only eleven manuscripts illustrate the novel; three Greek, two Russian, and three Arabic ones, while the illustration of the parable of The Futile Life is found in eight of them[8]

The codices are the following:

1. Jerusalem 42 (fol. 77) (11th century)[9],

2. Codex Ioannina-Cambridge (fol. 54) (12th century)[10],

3. Cambridge King’s College 338 (fol. 41v) (10th century, 976)[11],

4. Paris. gr. 1128 (fol. 68) (10th century, 976)[12],

5. Leningrad 71 (first quarter of the 17th century)[13], and

6a. Vaticanus arabe 692 (Assemani 88) (fol. 42) (15th), 6b. Paris arabe 273 (Suppl. 110) (fol. 42) (1497), 6c. Paris arabe 274 (Suppl. 113) (fol. 55) (1494)[14]

At this point, it is worth adding a twelfth manuscript in the same list, Paris gr. 36 (fol. 303v) (14th century). A man sitting on a tree and tasting some fruit is depicted in the center of the composition. Around him, we recognize a unicorn, five dragons and other animals and beasts, which symbolize brevity, insecurity, futility, and, ultimately, the transient nature of life on earth[15]

In addition, this narrative is illustrated at least in three more manuscripts, which belong to the category of specific sacred texts of liturgical use, the psalteries:

1. Psalter of London 19352 (fol. 182) (1066, Monastery of Stoudios/Monastery of Saint John the Forerunner at Stoudios), where the scene also illustrates Psalm CXLVI (144.4)[16],

2. Barberini (Vat. gr. 372) (fol. 231v), where the scene also illustrates Psalm CXLVI (144.4)[17], and

3. A Russian manuscript, the Psalter of Kiev or, alternatively, Psalter of Spryridonos (Leningrad/St Petersburg State Public Library “Saltykov-Shchedrin”) (fol. 6) (Moscow or Kiev, 1397), where the psalm itself is illustrated (here numbered as CXLIII/143,3-4)[18]

In other words, there is a second category of manuscripts, where this parable is chosen consistently and used individually to illustrate the Psalm of David, 143.3-4:

“[3] For the enemy hath persecuted my soul; he hath smitten my life down to the ground; he hath made me to dwell in darkness, as those that have been long dead. [4] Therefore is my spirit overwhelmed within me; my heart within me is desolate”

At the same time, it is worth mentioning that the lost miniature Codex 43 of the Holy Monastery of Iviron (fol. 135) in Mount Athos illustrates the novel Barlaam and Josaphat, which probably was identified with the collection of the Codex Cambridge-King’s College[19]

3. Unicorn: A two-sided coin. From the ancient world to the parable of the futile life

Reading the parable, one observes the existence of an ensemble of ancient symbols imbued with the Christian ideal, which can be further interpreted, especially when they decorate pages of sacred and liturgical texts, like the above, and/or the interior walls/mural sections of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine churches. However, the above parabolic story appears neither in the written texts nor in the various iconographical models in its full form, meaning with all the above-mentioned symbols

Nevertheless, before proposing a comprehensive interpretation for the full version of the above parable, it is worthwhile to make a special reference to the symbol of the unicorn, namely to an emblematic figure, apparently, with pagan origins, the potential of which exceeded the spiritual boundaries of the ancient world, imbued very early in the Christian tradition, often replacing even contradictory intra-religious concepts

Firstly, the unicorn is a mythical creature, which has been described since the (Pre) Historic cultures of the Fertile Crescent, and also since the Graeco-Roman Antiquity as a beast, impossible to be captured by humans, usually taking the form of a horse (sometimes of a wild bull, a goat, an ox, or even a rhino, especially in Africa - vd. primary sources below) with a characteristic large, pointed, spiral horn protruding from its forehead, giving the creature an impressive beauty. References of it are found, inter alia, in the following ancient writers:

• Ctesias (4th century B.C.), Indica [summary from Saint Photius I, Patriarch of Constantinople, 9th century, The Library/Biblioteca/Myriobiblon, 72]:

“In India there are wild asses [i.e. the Monokerata (Unicorns)] large as horses, or even larger. Their body is white, their head dark red, their eyes bluish, and they have a horn in their forehead about a cubit in length. The lower part of the horn, for about two palms distance from the forehead, is quite white, the middle is black, the upper part, which terminates in a point, is a very flaming red. Those who drink out of cups made from it are proof against convulsions, epilepsy, and even poison, provided that before or after having taken it they drink some wine or water or other liquid out of these cups. The domestic and wild asses of other countries and all other solid-hoofed animals have neither huckle-bones nor gall-bladder, whereas the Indian asses have both. Their huckle-bone is the most beautiful that I have seen, like that of the ox in size and appearance; it is as heavy as lead and of the color of cinnabar all through. These animals are very strong and swift; neither the horse nor any other animal can overtake them. At first, they run slowly, but the longer they run their pace increases wonderfully, and becomes faster and faster. There is only one way of catching them. When they take their young to feed, if they are surrounded by a large number of horsemen, being unwilling to abandon their foals, they show fight, but with their horns, kick, bite, and kill many men and horses. They are at last taken, after they have been pierced with arrows and spears; for it is impossible to capture them alive. Their flesh is too bitter to eat, and they are only hunted for the sake of the horns and huckle-bones”[20]

• Strabo (1st century B.C. - 1st century A.D.), Geographica (15.1.56)

“Now these customs are very novel as compared with our own, but the following are still more so. For example, Megasthenes says that the men who inhabit the Caucasus have intercourse with the women in the open and that they eat the bodies of their kinsmen; and that the monkeys are stone-rollers, and, haunting precipices, roll stones down upon their pursuers; and that most of the animals which are tame in our country are wild in theirs. And he mentions horses with one horn and the head of a deer; and reeds, some straight up thirty fathoms in length, and others lying flat on the ground fifty fathoms, and so large that some are three cubits and others six in diameter”[21]

• Pliny the Elder (1st century A.D.), Natural History (8.31)

“But that the fiercest animal is the Monocerotem (Unicorn), which in the rest of the body resembles a horse, but in the head a stag, in the feet an elephant, and in the tail a boar, and has a deep bellow, and a single black horn three feet long projecting from the middle of the forehead. They say that it is impossible to capture this animal alive”[22]

• Philostratus (1st - 2nd century A.D.), Life of Apollonius of Tyana (3.2)

“And they say that wild asses are also to be captured in these marshes [of the Indian River Hydroates], and these creatures have a horn upon the forehead [Onoi Monokerata (Unicorns)], with which they butt like a bull and make a noble fight of it; the Indians make this horn into a cup, for they declare that no one can ever fall sick on the day on which he has drunk out of it, nor will anyone who has done so be the worse for being wounded, and he will be able to pass through fire unscathed, and he is even immune from poisonous draughts which others would drink to their harm. Accordingly, this goblet is reserved for kings, and the king alone may indulge in the chase of this creature. And Apollonios says that he saw this animal, and admired its natural features; but when Damis asked him if he believed the story about the goblet, he answered : ‘I will believe it, if I find the king of the Indians hereabout to be immortal; for surely a man who can offer me or anyone else a draught potent against disease and so wholesome, he not be much more likely to imbibe it himself, and take a drink out of this horn every day even at the risk of intoxication? For no one, I conceive, would blame him for exceeding in such cups”[23]

• Aelian (2nd century A.D.), On Animals (3.41 and 4.52)

“India produces Hippoi Monokerata (one-horned horses), they say, and the same country fosters Onoi Monokerata (one-horned asses). And from these horns they make drinking-vessels, and if anyone puts a deadly poison in them and a man drinks, the plot will do him no harm. For it seems that the horn both of the horse and of the ass is an antidote to the poison

&

I have learned that in India are born Wild Asses (Onoi) as big as horses [i.e. the Monokerata (Unicorns)]. All their body is white except for the head, which approaches purple, while their eyes give off a dark blue colour. They have a horn on their forehead as much as a cubit and half long; the lower part of the horn is white, the upper part is crimson, while the middle is jet-black. From these variegated horns, I am told, the Indians drink, but not all, only the most eminent Indians, and round them at intervals they lay rings of gold, as though they were decorating a beautiful arm of a statue with bracelets. And they say that a man who has drunk from this horn knows not, and is free from, incurable diseases: he will never be seized with convulsions nor with the sacred sickness (epilepsy), as it is called, nor be destroyed by poisons. Moreover, if he had previously drunk some deadly stuff, he vomits it up and is restored to health

It is believed that Asses, both the tame and the wild kind, all the world over and all other beasts with uncloven hoofs are without knucklebones and without gall in the liver; whereas those horned Asses of India, Ktesias (Ctesias) says, have knucklebones and are not without gall. Their knucklebones are said to be black, and if ground down are black inside as well. And these animals are far swifter than any ass or even than any horse or any deer. They begin to run, it is true at a gentle pace, but gradually gather strength until to pursue them is, in the language of poetry, to chase the unattainable

When the dam gives birth and leads her new-born colts about, the sires herd with, and look after, them. And these Asses frequent the most desolate plains in India. So when the Indians go to hunt them, the Asses allow their colts, still tender and young, to pasture in their rear, while they themselves fight on their behalf and join battle with the horsemen and strike them with their horns. Now the strength of these horns is such that nothing can withstand their blows, but everything gives way and snaps or, it may be, is shattered and rendered useless. They have in the past even struck at the ribs of a horse, ripped it open, and disembowelled it. For that reason, the horsemen dread coming to close quarters with them, since the penalty for so doing is a most lamentable death, and both they and their horses are killed. They can kick fearfully too. Moreover, their bite goes so deep that they tear away everything that they have grasped. A full-grown Ass one would never capture alive: they are shot with javelins and arrows, and when dead the Indians strip them of their horns, which, as I said, they decorate. But the flesh of Indian Asses is uneatable, the reason being that it is naturally exceedingly bitter”[24]

• Cosmas Indicopleustes (6th century A.D.), Christian Topography (11.335)

“Cameleopards are found only in Ethiopia. They also are wild creatures and undomesticated. In the palace one or two that, by command of the King, have been caught when young, are tamed to make a show for the King's amusement. When milk or water to drink is set before these creatures in a pan, as is done in the King's presence, they cannot, by reason of the great length of their legs and the height of their breast and neck, stoop down to the earth and drink, unless by straddling with their forelegs. They must therefore, it is plain, in order to drink, stand with their forelegs wide apart. This animal also I have delineated from my personal knowledge of it”[25]

For the origin of the subject of the unicorn, as well as for the mythological tradition that evolved through the interpretation of the iconography in question, there is an extensive international bibliography, which seems to focus mainly on the western evolution of the myth, sporadically referring to the corresponding east, almost always insisting on issues of historical and artistic interest, but forgetting to offer observations on the cultural anthropology of religions[26]

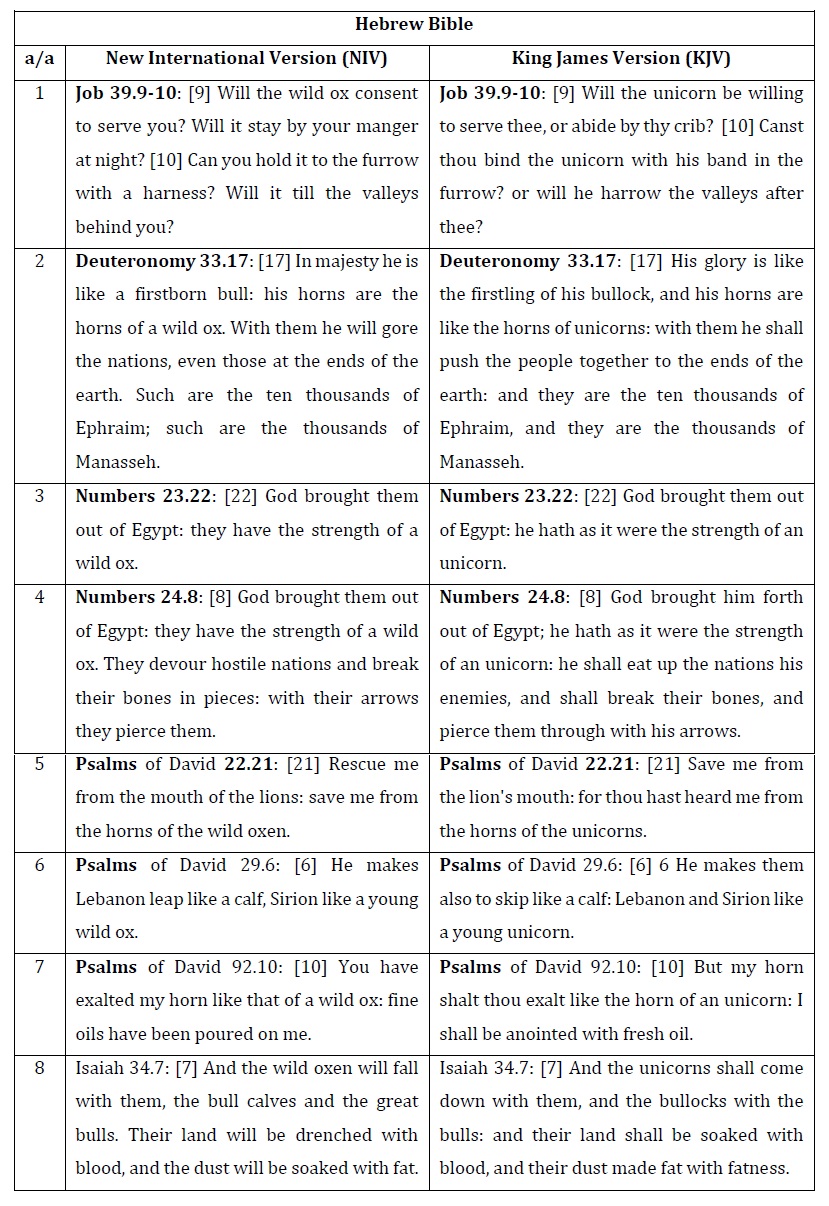

Of course, we can mention the numerous references to unicorns in various passages of the Old Testament of the Hebrew Bible that provoke a historical, religious, and, in general, sociological-ethical interest, consistent to some extent with the interpretative analysis of the present research. More specifically, an animal called the re’em (also: reem, Hebrew: רְאֵם), translated as a unicorn or a wild ox, is mentioned several times (over eight times) in the Old Testament, often as a metaphor representing steadfast strength, loyalty and devotion, or even the power of fertility, which constantly renews any human society, offering blessings to its members, judging by the symbolic dimension of the horns, which act as duplicates of the cornucopia in a predominantly farming cultural community. Its appearance seems to resemble the morphological features of the aurochs (known in Latin as bos primigenius). This view finds support in the ancient natural and cultural environment of Assyria, where the word rimu comes from, in order to convey metaphorically the meaning of the physical (possibly spiritual) power, in the sense of the depiction of a powerful, fierce, wild mountain bull with large horns[27]. Ιn Jewish folklore, according to R. Graves and R. Patai (2014) the re’em is presented to the minds of people as being larger than a mountain, capable of destroying even the Jordan River with its dung. Indeed, in order to survive during the period of the Cataclysm, Noah had tied its horns on the Ark, so that its nostrils could protrude from the marine construction, easing the animal’s breathing. Also, King David, while still living as a shepherd in the fields, lost the horn from which he was playing music on a mountain. Walking around, he fell on a re’em, which was sleeping. Suddenly, the animal began to chase him, until it caught him, lifting him as high as the sky. Having lost every hope, David prayed to God to save him. Then, a lion passed in front of the re’em. As the re’em bowed to the animal, King David climbed off but was threatened, ex novo, by the lion. He prayed again and another animal passed by, so that the lion hunted it down and left David harmless[28]

The following comparative table of the translated passages referring to the unicorn form is indicative[29]

Returning, then, to the parable of the Futile Life, it is observed that the narrative, including the figure of the unicorn, with any slight variations and in the most complete form, unfolds as follows; encompassing a multitude of core values of the early and middle Christianity, focusing initially on the symbol of the unicorn, and subsequently on the so-called “Tree of Life”

A man was hunted by a fierce unicorn. The figure of the unicorn has conveyed, over time, a variety of primitive ideas/concepts, even contradictory at points, depending on the circumstances (e.g. virginity, purity, health, death, good, evil), on a symbolic level. In summary, it is stated that in Christian ideology the unicorn is usually a symbol of purity and it symbolizes Christ, but its presentation/depiction is not so widely spread[30]. Symbols of the unicorn are found in the works of the Fathers of the Eastern and Western Churches, in the same interpretative light, indicatively as follows:

• Saint John Chrysostom (3rd-4th centuries): Comments to the Psalm of David 91 (P. Migne, P.G., 763-764),

• Saint Basil the Great (4th century): Sermon about the Psalm of David 28 (P. Migne, P.G., 30.80, par. 5), and

• Saint Isidore of Seville (6th-7th centuries): Etymologiae (P. Migne, P.L., LXXXII, 435)

Moreover, in Codex 61 of Pantokratoros Monastery, in Mount Athos, which contains one hundred and fifty Psalms and nine Odes of David (with philological errors and other omissions), in fol. 109v is found a miniature of 6 x 6.5 cm, with a rare depiction of the Virgin dressed as a noblewoman, with a diadem and a red looming robe, breastfeeding a unicorn shaped as a goat, a long wavy blue horn in its head, similar to the illustrated unicorn of Middle-Byzantine Codex 48 of the Evangelical School of Smyrna (fol.75b) (11th century)[31]. The performance is accompanied by the inscription: “Περί τοῦ υἱοῦ το(ῦ) Θ(εο)ῦ καθώς ἐθήλασεν τὴν Παναγίαν Θεοτόκον” (English translation: “About the Son of God, while he’s breastfed by Virgin Mary/Panagía Theotóko”), a fact which proves that the unicorn in Christian thought can be allegorically linked to the Birth of Christ[32]. In another manuscript, the Codex 4 of Dionysiou Monasteri, also in Mount Athos, which contains the “Four Gospels”, the “Letter to Carpian” and “Rules (Canons) of Correspondence by Eusebius of Caesarea”, depicted a goat-like blue unicorn, torn and chained (fol. 9v)[33]

Emphasis is also given to the concept of virginity in the 36th Chapter of the Physiologus - a didactic Christian text either written or compiled in Greek by an unknown author and traditionally dated to the 2nd century A.D. - which is wholly devoted to the description of the unicorn. There, it is stated that if a virgin sits alone in the woods the unicorn will approach her and rest its head on her feet, apparently enchanted by the virgin’s beauty and purity of soul[34]

Nevertheless, if the unicorn in Christian art symbolizes virginity, chastity, goodness, and generally any good-beneficial meaning that can be associated with the incarnation of the Word (Med. Greek: “Λόγος”) of God, that is, Jesus Christ, then why, at the same time, concepts of confrontational character, such as evil, threat, and ineluctable death, are sometimes mingled in the presentation of the animal? The answer lies in the story of the parable of the Futile Life, of which the interpretation of the continued narrative leads to philosophical-theological conclusions[35]

In his attempt to escape, the man hunted by the fierce unicorn fell into a deep ravine (Med. Greek: “βόθρος”), symbolizing the vicious world where people live, act and meet physical death. This man, motivated by a burning inner passion for conquering the rare/different, the strangely beautiful which, in other words, is not regularly found among the animate and inanimate beings of the real worldwide, has probably tried to capture and tame the unicorn, in order to satisfy a vain (strange to Christian virtue) ambition. Now the unicorn is acting in thought as a weapon/bait of the enemies of the Christian faith, who are trying in every way to deceive man, cut off from his journey to seek and conquer superior spiritual ideas, such as temperance and prayer. As the man allows for this spiritual deterioration, his course is set in a series of loose passages, which transform his own life into a dead end, a futile life

During his fall, however, the man managed to get caught from the branches of a tree, which reflects the eternal paradise and sustainable Tree of Life, while supporting his legs on a base, in the passage between life and death[36]. Then, he looked carefully at the tree and noticed that he was about to fall because two mice (one white and the other black), were roaming his roots repeatedly, day and night. In the depth of the ravine, ready to swallow the unfortunate man, lurked Hades in the form of a great dragon. Also, the base on which he lay consists of four poisonous snakes/vipers/echidnae, (Med. Greek: “ἔχιδναι”, “ἀσπίδαι”), which symbolize the unstable composition of the body (Med. Greek: “ἐπί τεσσάρων σφαλερῶν καί ἀστάτων στοιχείων”). As he looked up desperately, he saw that some of the branches of the tree dripped a little honey, which in this case refers to an allegorical symbol of terrestrial pleasure (Med. Greek: “τῶν τοῦ κόσμου ἠδέων”). Consequently, man becomes dependent on the hedonistic indulgences (Med. Greek: “τῆς ἡδύτητος ἐκκρεμής”). Though he had already realized that death was inevitably approaching, ignoring at the same time all the misery of the environment, even the perishable and finite background of his human existence, he began to eat with pleasure the honey flowing from the branches

The version with the unicorn seems to be not the most common one - perhaps because of the strong (but, at the same time, ambiguous for the Christian culture) symbolism that the presence of this ancient mythical creature hides - in the wall painting, of the post-Byzantine period, including the iconographic example from the temple of Saint Demetrios in the coastal city of Thessaloniki. In fact, the iconographical examples of frescoes are few. Two general features can be identified: a) these frescoes date back to the Post-Byzantine period (especially between the period between the 15th and the 18th century), and b) their matter is the Tree of Life, whereas the unicorn image is usually missing. Additionally, most of them are also missing the dragon. The Tree of Life is an iconography often depicted in Post-Byzantine painting, especially in the narthexes of churches[37]. Nevertheless, these frescoes, despite the absence of the unicorn, include the fundamental iconographic elements of the parable, namely the mice that roam the roots of the Tree, the persecuted man, and the honey dripping. Therefore, there is no doubt that this theme comes from the novel Barlaam and Josaphat. Other scenes from the novel are not illustrated in frescoes, except for the Noul Neamț Monastery (Chițcani Monastery) in Moldova, where the parable of the Futile Life is not illustrated, but thirty-one other episodes of the Novel, mainly from the life of Josaphat[38].

The oldest of the frescoes illustrating the above parable is found in the temple of Saint Demetrios in Thessaloniki, at the southern pilaster of the tribelum-portico, at the western entrance of the narthex (Fig. 1). Today, this fresco is very worn out, considered almost as destroyed (chipped) and unsavable. Nowadays, it is mainly known through previous bibliographical references and sketches. It is dated back to 1474-1493. Also, the colour choices of the artistic composition can only be identified with difficulty[39]

In this composition, the man on the Tree of Life tastes with pleasure the honey dripping from the Sky, which is symbolically depicted as a semicircle at the top of the fresco, where there is, also, the following misspelled inscription: “ἡ γληκήτης” (the correct form in Med. Greek is: “ἡ γλυκύτης”). The Tree is supported by the dragon’s mouth, while the personalized “Νight” and “Day” are depicted as snakes/dragons wrapped around the Tree trunk, suffocating it. Two other small winged dragons/demonic figures, on both sides of the Tree, which are inscribed “blood” (Med. Greek: “αίμα”, the right grammar type being “αἷμα”) and “bile” (Med. Greek: “χολή”) are considered to be new iconographic elements. On the one hand, the scholars Georgios and Maria Sotiriou (1952), who studied carefully the wall-painting of the temple, mention that the composition is complemented by the presence of a small animal, which is identified as a rhino - not as a unicorn - that lurks the roots of the Tree, an image that has not been saved nevertheless[40]. On the other hand, Sirarpie Der Nersessian states that the unicorn is not depicted[41]. It is also difficult to distinguish the upper part of the body of a female figure in a cloak (perhaps the Virgin Mary), which, on the one hand, is not easily identified, and on the other hand is obviously not related to any of the narrative plots of the parable

Finally, it is noted that the same representation is found in some other iconographical circles, in the wider area of the Moldovlachian region. Thus, it is depicted in the narthex of the Holy Trinity Church of Cozia Monastery in Romania (15th century) and in the narthex of the Chapel of Peter and Paul of the same Monastery (15th century), without the presence of the unicorn in the latter monument, and next to the representation of Jonah’s parable[42]. There is also a complete thematic version in the temple of Saint Marc in Venice, Italy, which is also relevant[43]

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, it seems that the careful examination of the various examples of medieval monumental and miniature art provides a significant feedback on the interpretation of the parable of the Futile Life. At the heart of the new approach, there is the multifaceted, timelessly and culturally, controversial figure of the unicorn (when it exists). More specifically, as found through the citation of a variety of Greek, Latin and Hebrew written sources, on the one hand, the exterior of the unicorn itself may generally differ - depending on the cultural reference environment - and on the other hand the importance behind this image takes diametrically opposite semiotic dimensions, symbolizing anthropologically fundamental concepts, such as goodness, purity, beauty, or virginity, even Christ himself (e.g. Comments to the Psalm of David 91 by Saint John Chrysostom, Sermon about the Psalm of David 28 by Saint Basil the Great, Etymologiae of Saint Isidore of Seville, Codex 61 of Pantokratoros Monastery, in Mount Athos, Codex 48 of the Evangelical School of Smyrna, Codex 4 of Dionysiou Monasteri, also, in Mount Athos)

In the case of our study, the parable of the Futile Life highlights, perhaps in the most dynamic way, the malicious semiotic interpretation of the unicorn, speaking to the monumental painting of the Post-Byzantine/Medieval Period (e.g. Saint Demetrios in Thessaloniki, Holy Trinity Church and Chapel of Peter and Paul of the of the Cozia Monastery in Romania, of Saint Marc in Venice). In fact, this shape of the unicorn, coloured with negative notions about the human (corporal and spiritual) condition, functions as part of a wider symbolic pantheon (e.g. cosmic figures, beasts, deep ravine, blood, bile), where the idea of wickedness prevails in human/earthly life, that is, of the perishable end that runs through human existence, since its Creation (Tree of Life)

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Manuscript sources

Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, Codex Ioannina-Cambridge, fol. 54

Cambridge, Library of Cambridge King’s College, Cambridge King’s College 338, fol. 41v

Izmir (Smyrna), Library of Evangelical School of Smyrna, Codex 48 of the Evangelical School of Smyrna, fol.75b

Jerusalem, Archival of Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem 42 (Codex Hierosolymitanus 42), fol. 77

London, British Library, Psalter of London 19352, fol. 182

Monastic Republic of Mount Athos, Chalcidice, Library of Dionysiou Monastery, Codex 4, fol. 9v

Monastic Republic of Mount Athos, Chalcidice, Library of Pantokratoros Monastery, Codex 61, fol.109v

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris arabe 273, Suppl. 110, fol. 42

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris arabe 274, Suppl. 113, fol. 55

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris gr. 36, fol. 303v

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris gr. 1128, fol. 68

St Petersburg, Russian National Library “Saltykov-Shchedrin”, Leningrad 71

St Petersburg, Russian National Library “Saltykov-Shchedrin”, Psalter of Spryridonos (Moscow or Kiev Psalter of 1397), fol. 6

Vatican City State, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Barberini, Vat. gr. 372, fol. 231v

Vatican City State, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vaticanus arabe 692, Assemani 88, fol. 42

Printed sources

BIBLE GATE WAY - “Holy Bible, John Wycliffe Bible (WYC)” [Online], 2001. [Acessed 15 August 2018]. Available at https://www.biblegateway.com

BIBLE GATE WAY - “Holy Bible, King James Version (KJV)” [Online], 1987. [Acessed 15 August 2018]. Available at https://www.biblegateway.com

BIBLE GATE WAY - “Holy Bible, New International Version (NIV)” [Online], 2011. [Acessed 15 August 2018]. Available at https://www.biblegateway.com

BIBLE GATE WAY - “Holy Bible, Rheims Bible (DRA)” [Online], 1899. [Acessed 15 August 2018]. Available at https://www.biblegateway.com

CARMODY, Francis - Physiologus, The Very Ancient Book of Beasts, Plants and Stones. San Francisco, California, USA: The Book Club of California, 1953

CONYBEARE, Frederick Cornwallis - The life of Apollonius of Tyana: The epistles of Apollonius and the treatise of Eusebius. London, Massachusetts, USA: W. Heidemann, 1912

FREESE, John Henry - The library of Photius. London, UK: Society for promoting Christian knowledge and New York City, New York, USA: The Macmillan Company, 1920

HORACE, Jones Leonard - The geography of Strabo. London, UK: Heinemann, 1917

M’CRINDLE, John Watson - The Christian topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian monk. New York City, New York, USA: B. Franklin, 1967

MIGNE, Jacques-Paul - Patrologiae cursus completus: sive biblioteca universalis, integra, uniformis, commoda, oeconomica, omnium SS. Patrum, doctorum scriptorumque eccelesiasticorum qui ab aevo apostolico ad usque Innocentii III tempora floruerunt... [Series Latina, in qua prodeunt Patres, doctores scriptoresque Ecclesiae Latinae, a Tertulliano ad Innocentium III. Parisiis: excudebatur et venit apud J.P. Migne, 1841

MIGNE, Jacques-Paul - Patrologiae cursus completus: Seu biblioteca universalis, integra, uniformis, commoda, oeconomica, omnium SS. Patrum, doctorum scriptorumque eccelesiasticorum, sive latinorum, sive graecorum, qui ab aevo Apostolico ad aetatem innocentii III (ann.1216) pro latinis et ad Photii tempora (ann. 863) pro graecis floruerunt: Recusio Chronologica [Series Graeca]. Turnholti, Belgium: Brepols, 1969

ΠΛΕΞΊΔΑΣ, Ιωάννης - Βίος Βαρλάαμ και Ιωάσαφ (Αγίου Ιωάννου Δαμασκηνού). Τρίκαλα: Πρότυπες Θεσσαλικές Εκδόσεις, 2008

RACKHAM, Harris, et alli - Pliny, the Elder. Natural history. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press, 2014 (revised edition)

RATCLIFFE-WOODWARD, George; MATTINGLY, Harold - Barlaam and Ioasaph (by Saint John Damascene). Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press, 1983

SCHOLFIELD, Alwyn Faber - Aelian On the Characteristics of Animals. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press, 1971

STRZYGOWSKI, Josef - Der Bilderkreis Des Griechischen Physiologus, Des Kosmas Indikopleustes Und Oktateuch: Nach Handschriften Der Bibliothek Zu Smyrna: Mit 40 Lichtdrucktafeln Und 3 Abbildungen Im Texte. Groningen: Bouma’s Boekhuis, 1969

ZUCKER, Αrnaud - Physiologos: le bestiaire des bestiaries. Grenoble: Editions Jérôme Millon, 2004

Studies

AAVITSLAND, Kristin Bliksrud - Imagining the Human Condition in Medieval Rome: The Cistercian fresco cycle at Abbazia delle Tre Fontane. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2012 [ Links ]

ALFÖLDI-ROSENBAUM, Elisabeth; WARD-PERKINS, John - Justinianic Mosaic Pavements in Cyrenaican Churches. Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1980 [ Links ]

BOVINI, Giuseppe - Ravenna. Città d'arte. Ravenna: Edizioni A. Longo, 1970 [ Links ]

BUCCI, Giovanna - L'albero Della Vita Nei Mosaici Pavimentali Del Vicino Oriente. Bologna: University Press, 2001 [ Links ]

CHILD, Heather; COLLES, Dorothy - Christian Symbols, Ancient and Modern: A Handbook for Students. London, UK: G. Bell and Sons, 1971 [ Links ]

CONYBEARE, Frederick Cornwallis - The Barlaam and Josaphat Legend in the Ancient Georgian and Armenian Literatures [Analekta Gorgiana 64]. Piscataway, New Jersey, USA: Gorgias Press, 2008 [ Links ]

COOK, Roger - The tree of title: Image for the cosmos. New York City, New York, USA: Thames and Hudson, 1995 [ Links ]

DEICHMANN, Friedrich Wilhelm - Ravenna, Hauptstadt des spätantiken Abendlandes. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner, 1969 [ Links ]

FARIOLI-CAMPANATI, Raffaella - Pavimenti Musivi di Ravenna Paleocristiana. Ravenna: Edizioni A. Longo, 1975 [ Links ]

FARIOLI-CAMPANATI, Raffaella - Ravenna Romana e Bizantina. Ravenna: Edizioni A. Longo, 1977 [ Links ]

GODBEY, Allen - “The Unicorn in the Old Testament”. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 56/3 (1939), pp. 256-296 [ Links ]

GOWERS, William - “The Classical Rhinoceros”. Antiquity XXIV (1950), pp. 61-71 [ Links ]

GRAVES, Raphael; PATAI, Robert - Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis. New York City, New York, USA: Rosetta Books, 2014 [ Links ]

HIRSCH, Emil; CASANOWICZ, Immanuel - “Unicorn”. in SINGER, Isidore - The Jewish Encyclopedia. A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Tomes to the Present Day, v. XII. New York City, New York, USA and London, UK: Funk and Wagnalls, 1903, p. 344 [ Links ]

HUMPHREYS, Humphrey - “The Horn of the Unicorn”. Antiquity XXVII (1953), pp. 15-19 [ Links ]

ΚΑΖΑΜΙΑ, Μαρία - Μνημειακή Τοπογραφία της Χριστιανικής Θεσσαλονίκης. Οι ναοί 4ος-8ος αι. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εκδόσεις Γράφημα [ Links ], 2009

KLAUSER, Thomas - Reallexikon fur Antike und Christentum (RAC): Sachworterbuch zur Auseinandersetzung des Christentums mit der antiken Welt, B. IV. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1959, entry: “Einhorn”, pp. 840-862 (H. BRANDERBURG) [ Links ]

ΛΑΜΠΡΟΥ, Σπυρίδων - Κατάλογος των εν ταις βιβλιοθήκαις τον Αγ. Όρους ελληνικών κωδίκων. Cambridge: University Press, [ Links ] 1895

LANG, David Marshall - “St. Euthymius the Georgian and the Barlaam and Ioasaph Romance”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 17.1/2 (1955), pp. 306-325 [ Links ]

LANG, David Marshall - “The Life of the Blessed Iodasaph: A New Oriental Christian Version of the Barlaam and Ioasaph Romance” [Jerusalem, Greek Patriarchal Library: Georgian MS 140]. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 20.1/3 (1957), pp. 389-407 [ Links ]

LANG, David Marshall - Balavariani: A Tale from the Christian East [Jerusalem Greek Patriarchal Library: Georgian MS]. Los Angeles, California, USA: California University Press, 1966 [ Links ]

LAVERS, Chris - “The Ancients’ One-Horned Ass: Accuracy and Consistency”. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 40 (1999), pp. 327-352 [ Links ]

LECLERCQ, Henri - “Licorne”. in CABROL, Fernard; LECLERCQ, Henri (ed.) - Dictionnaire d'archeologie chretienne et de liturgie, v. IX. Paris: Letouzey et Ané, 1928, pp. 613-614 [ Links ]

MERMIER, Guy - “The Romanian Bestiary: An English Translation and Commentary on the Ancient ‘Physiologus’ Tradition”. Mediterranean Studies 13 (2004), pp. 17-55 [ Links ]

METTINGER, Tryggve - The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2-3. Winona Lake, Indiana, USA: Eisenbrauns, 2007 [ Links ]

MINER, Dorothy Eugenia - “The ‘Monastic’ Psalter of the Walters Art Gallery”. in WEITZMANN, Kurt (ed.) - Late Classical and Medieval Studies in honor of Albert Mathias Friend, Jr. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press, 1955 [ Links ]

ΜΠΑΚΙΡΤΖΉΣ, Χαράλαμπος - Η βασιλική του Αγίου Δημητρίου. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εταιρεία Μακεδονικών Σπουδών [ Links ], 1972

MUÑOZ, Antonio - “Le representazioni alle goriche della vita nell’artebizantina”. L’Arte VII (1904), pp. 130-145 [ Links ]

NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L'illustration du roman de Barlaam et Joasaph, v. 1-texte, v. 2-album. Paris: E. de Boccard, 1937 [ Links ]

NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L'illustration des psautiers grecs du Moyen Age, II, Londres, Add. 19352. Paris: C. Klincksieck, 1970 [ Links ]

ΞΥΓΓΌΠΟΥΛΟΣ, Ανδρέας - Σχεδίασμα ιστορίας της θρησκευτικής ζωγραφικής μετά την άλωσιν. Αθήναι: H εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία, 1957 [ Links ]

ΠΕΛΕΚΑΝΊΔΗΣ, Στυλιανός - Οι Θησαυροί του Αγίου Όρους, Σειρά Α΄. Εικονογραφημένα Χειρόγραφα, παραστάσεις - επίτιτλα - αρχικά γράμματα, Μ. Ιβήρων, Μ. Αγίου Παντελεήμονος, Μ. Εσφιγμένου, Μ. Χιλανδαρίου, τ. Β΄, 1973 [ Links ]

ΠΕΛΕΚΑΝΙΔΗΣ, Στυλιανός - Οι Θησαυροί του Αγίου Όρους, Σειρά Α΄. Εικονογραφημένα Χειρόγραφα, παραστάσεις - επίτιτλα - αρχικά γράμματα, Μ. Μεγίστης Λαύρας, Μ. Παντοκράτορος, Μ. Δοχειαρίου, Μ. Καρακάλου, Μ. Φιλοθέου, Μ. Αγίου Παύλου, τ. Γ΄. Αθήναι: Πατριαρχικό Ίδρυμα Πατερικών Μελετών, Εκδοτική Αθηνών [ Links ], 1979

POPOVA, Olga - La Miniature Russe, XIe-début du XVIe siècle. Leningrad: Editions D'art Aurora, 1975 [ Links ]

ΠΡΟΒΑΤΑΚΗΣ, Θωμάς - Ο διάβολος εις την βυζαντινήν τέχνην: συμβολή εις την έρευναν της ορθοδόξου ζωγραφικής και γλυπτικής. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εκδόσεις Ρέκος, 1980 [ Links ]

RÉAU, Louis - Iconographie de l'art chretien, v. 1-2. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1955-1956 [ Links ]

RUICKBIE, Leo - The Impossible Zoo: An encyclopedia of fabulous beasts and mythical monsters, entry: “Licorne”, without numbers on the pages. London: Hachette, 2016 [ Links ]

ΣΑΜΠΑΝΙΚΟΥ, Εύη - Η εικονογράφηση της σκηνής του Μαινόμενου Μονοκέρωτος από το μυθιστόρημα Βαρλαάμ και Ιωασάφ στην Ελλαδική μεταβυζαντινή τοιχογραφία. Ιωάννινα: Επιστημονικές Επετηρίδες Πανεπιστημίου Ιωαννίνων, «Δωδώνη», Φιλοσοφική Σχολή, Τμήμα Ιστορίας και Αρχαιολογίας, 1990, pp. 127-157 [ Links ]

SCHULZ, Siegfried - “Two Christian Saints? The Barlaam and Josaphat Legend”. India International Centre Quarterly 8/2 (1981), pp. 131-143 [ Links ]

ȘTEFĂNESCU, Ioan - “Le Roman de Barlaam et Ioasaph Illustré en peinture”. Byzantion 7 (1932), pp. 347-369 [ Links ]

ΣΩΤΗΡΙΟΥ, Γεώργιος - “Η γλυκύτης τού κόσμου”. Ημερολόγιον τής Μεγάλης Ελλάδος 8 (1929), pp. 111-116 [ Links ]

ΣΩΤΗΡΙΟΥ, Γεώργιος; ΣΩΤΗΡΊΟΥ, Μαρία - Η βασιλική του Αγίου Δημητρίου Θεσσαλονίκης Αθήναι: H εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία, 1952 [ Links ]

ΤΣΙΡΕΛΗ, Ευλαμπία - Το Ιερό Δέντρο. Οι μύθοι και συμβολισμοί του. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εκδόσεις Δαίδαλος, 2014 [ Links ]

VILLETTE, Jeanne - La résurrection du Christ dans l’art chrétien du Iie au VIIe siècle. Paris: Henri Laurens, 1957 [ Links ]

VIZΚΕLETY, András - “Einhorn”. in KIRSCHBAUM, Engelbert; BANDMANN, Günter - Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, B. 1. Rom: Herder, 1968, pp. 590-593 [ Links ]

WALBRIDGE, John - The wisdom of the mystic East: Suhrawardi and platonic orientalism. Albany, New York, USA: State University of New York Press, 2001, pp. 129-130 [ Links ]

WEITZMANN, Kurt - Das Evangelion Im Skevophylakion Zu Lawra [Seminarium Kondakovianum VIII]. Praha: Institut Kondakov, 1936 [ Links ]

WEITZMANN, Kurt - Die Byzantinische Buchmalerei Des 9. Und 10. Jahrhunderts. Wien: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996 [ Links ]

ΧΑΛΚΙΑ, Eυγενία - Φανταστικά & Απόκοσμα. Ημερολόγιο 2012. Αθήνα: Βυζαντινό και Χριστιανικό Μουσείο Αθηνών, Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Τουρισμού [ Links ], 2012

Como citar este artigo | How to quote this article:

ORFANIDIS, Georgios - “Chased by a Unicorn. Re-Studying and De-Coding the Parable of the Futile Life in the Novel Barlaam and Josaphat (Medieval Greek Version)”. Medievalista 29 (Janeiro - Junho 2021), pp. 183-209. Disponível em https://medievalista.iem.fcsh.unl.pt/

Data recepção do artigo / Received for publication: 13 de Dezembro de 2019

Data aceitação do artigo / Accepted in revised form: 23 de Setembro de 2020

[1] WALBRIDGE, John - The wisdom of the mystic East: Suhrawardi and platonic orientalism. Albany, NY, USA: State University of New York Press, 2001, pp. 129-130

[2] LANG, David Marshall - “The Life of the Blessed Iodasaph: A New Oriental Christian Version of the Barlaam and Ioasaph Romance” (Jerusalem, Greek Patriarchal Library: Georgian MS 140). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 20.1/3 (1957), pp. 389-407

[3] LANG, David Marshall - Balavariani: A Tale from the Christian East [Jerusalem Greek Patriarchal Library: Georgian MS]. Los Angeles, California, USA: California University Press, 1966 [vd.: The Georgian translation probably served as a basis for the Greek text]; LANG, David Marshall - “St. Euthymius the Georgian and the Barlaam and Ioasaph Romance”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 17/2 (1955), pp. 306-325

[4] RATCLIFFE-WOODWARD, George; MATTINGLY, Harold - Barlaam and Ioasaph (by Saint John Damascene). Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press, 1983· ΠΛΕΞΊΔΑΣ, Ιωάννης - Βίος Βαρλάαμ και Ιωάσαφ (Αγίου Ιωάννου Δαμασκηνού). Τρίκαλα: Πρότυπες Θεσσαλικές Εκδόσεις, 2008· ΚΑΖΑΜΙΑ, Μαρία - Μνημειακή Τοπογραφία της Χριστιανικής Θεσσαλονίκης. Οι ναοί 4ος-8ος αι. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εκδόσεις Γράφημα, 2009, p. 316. Also, vd. footnote above

[5] CONYBEARE, Frederick Cornwallis - The Barlaam and Josaphat Legend in the Ancient Georgian and Armenian Literatures [Analekta Gorgiana 64]. Piscataway, New Jersey, USA: Gorgias Press, 2008

[6] SCHULZ, Siegfried - “Two Christian Saints? The Barlaam and Josaphat Legend”. India International Centre Quarterly 8/2 (1981), pp. 131-143

[7] ΠΡΟΒΑΤΆΚΗΣ, Θωμάς - Ο διάβολος εις την βυζαντινήν τέχνην: συμβολή εις την έρευναν της ορθοδόξου ζωγραφικής και γλυπτικής. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εκδόσεις Ρέκος, 1980, pp. 228-230. About a more specific description and interpretation of symbols see below

[8] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman de Barlaam et Joasaph, v. 1-texte - v. 2-album. Paris: E. de Boccard, 1937, v. 1, pp. 18-31

[9] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 2, fig. 24

[10] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 2, fig. 24

[11] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 2, pl. XXIII - fig. 87

[12] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 2, pl. LXVIII - fig. 266-267

[13] NERSESSIAN, Sirapie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 2, fig. 26 (Samara, priest Athanasios was the copier of the manuscript)

[14] Nersessian, S. Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 1, pp. 29-30 (There are no photographs)

[15] ΠΡΟΒΑΤΆΚΗΣ, Θωμάς - Ο διάβολος εις την βυζαντινήν τέχνην…, fig. 197

[16] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L'illustration des psautiers grecs du Moyen Age, II: Londres, Add. 19352. Paris: C. Klincksieck, 1970, pp. 57, 63-66, 69-70, fig. 286

[17] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L'illustration des psautiers grecs…, pp. 63, 69, fig. 332

[18] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L'illustration des psautiers grecs…, pp. 63 and beyond. Also, vd.: POPOVA, Olga - La Miniature Russe, XIe- début du XVIe siècle (Editions D'art Aurora: Leningrad, 1975), pl. 29 (et texte). It is also worth mentioning the following: a) Psalter Uglič, which repeats the structure of the Psalter of London 19352, and b) Serbian Psalter of Monache, which is a variant of this type ( = ΞΥΓΓΌΠΟΥΛΟΣ, Ανδρέας - Σχεδίασμα ιστορίας της θρησκευτικής ζωγραφικής μετά την άλωσιν. Αθήναι: H εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία, 1957, p. 72· POPOVA, Olga - La Miniature Russe…, p. 66)

[19] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L'illustration des psautiers grecs…, p. 63· ΛΑΜΠΡΟΥ, Σπυρίδων - Κατάλογος των εν ταις βιβλιοθήκαις τον Αγ. Όρους ελληνικών κωδίκων. Cambridge, UK: University Press, 1895, p. 149· ΠΕΛΕΚΑΝΊΔΗΣ, Στυλιανός - Οι Θησαυροί του Αγίου Όρους, Σειρά Α΄. Εικονογραφημένα Χειρόγραφα, παραστάσεις - επίτιτλα - αρχικά γράμματα, Μ. Ιβήρων, Μ. Αγίου Παντελεήμονος, Μ. Εσφιγμένου, Μ. Χιλανδαρίου, τ. Β΄. Αθήναι: Πατριαρχικό Ίδρυμα Πατερικών Μελετών, Εκδοτική Αθηνών, 1973), pp. 307-324, fig. 53-132

[20] Translated by FREESE, John Henry - The library of Photius. London, UK: Society for promoting Christian knowledge and New York City, New York, USA: The Macmillan Company, 1920, p. 95. For more details, vd. LAVERS, Chris - “The Ancients’ One-Horned Ass: Accuracy and Consistency”. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 40 (1999), pp. 327-352

[21] Translated by HORACE, Jones Leonard - The geography of Strabo. London, UK: Heinemann, 1917, p. 152

[22] Translated by RACKHAM, Harris. et alli - Pliny, the Elder. Natural history. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press, 2014 (revised edition), p. 81

[23] Translated by CONYBEARE, Frederick Cornwallis - The life of Apollonius of Tyana: The epistles of Apollonius and the treatise of Eusebius. London, Massachusetts, USA: W. Heidemann, 1912, p. 48

[24] Translated by SCHOLFIELD, Alwyn Faber - Aelian On the Characteristics of Animals. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press, 1971, p. 49, p. 68

[25] Translated by M’CRINDLE, John Watson - The Christian topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian monk. New York City, New York, USA: B. Franklin, 1967, p. 105

[26] Indicatively we can mention: CABROL, Fernard; LECLERCQ, Henri - Dictionnaire d'archeologie chretienne et de liturgie (DACL), v. IX. Paris: Letouzey et Ane, 1928, entry: “Licorne”, pp. 613-614 (Η. LECLERCQ, Fernard)· GOWERS, William - “The Classical Rhinoceros”. Antiquity XXIV (1950), pp. 61-71· HUMPHREYS, Humphrey - “The Horn of the Unicorn”. Antiquity XXVII (1953), pp. 15-19· RÉAU, Louis - Iconographie de l'art chretien, v. 1. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1955, pp. 89-91, 105, 118 & v. 2, 1956, pp. 191-192· KLAUSER, Thomas - Reallexikon fur Antike und Christentum (RAC): Sachworterbuch zur Auseinandersetzung des Christentums mit der antiken Welt, B. IV. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1959, entry: “Einhorn”, pp. 840-862, mainly, pp. 854-861 (BRANDERBURG, Henri)· KIRSCHBAUM, Engelbert; BANDMANN, Günter - Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, B. 1. Rom: Herder, 1968, entry: “Einhorn”, pp. 590-593 (VIZΚΕLETY, András)· DEICHMANN, Friedrich Wilhelm - Ravenna, Hauptstadt des spätantiken Abendlandes. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner, 1969, p. 106· BOVINI, Giuseppe - Ravenna. Città d'arte. Ravenna: Edizioni A. Longo 1970, p. 108· CHILD, Heather; COLLES, Dorothy - Christian Symbols, Ancient and Modern: A Handbook for Students. London, UK: G. Bell and Sons, 1971, pp. 216, 218, 241, where the hidden symbols behind the unicorn figure are presented in more detail· FARIOLI-CAMPANATI, Raffaella - Pavimenti Musivi di Ravenna Paleocristiana. Ravenna: Edizioni A. Longo, 1975, pp. 157, 161-162, 213· FARIOLI-CAMPANATI, Raffaella - Ravenna Romana e Bizantina. Ravenna: Edizioni A. Longo, 1977, pp. 51-55· ALFÖLDI-ROSENBAUM, Elisabeth; WARD-PERKINS, John - Justinianic Mosaic Pavements in Cyrenaican Churches. Roma: L'Erma di Bretschneider, 1980, pp. 55, 136, pl. 59· ΣΑΜΠΑΝΊΚΟΥ, Εύη - Η εικονογράφηση της σκηνής του Μαινόμενου Μονοκέρωτος από το μυθιστόρημα Βαρλαάμ και Ιωασάφ στην Ελλαδική μεταβυζαντινή τοιχογραφία. Ιωάννινα: Επιστημονικές Επετηρίδες Πανεπιστημίου Ιωαννίνων, «Δωδώνη», Φιλοσοφική Σχολή, Τμήμα Ιστορίας και Αρχαιολογίας, 1990, pp. 127-157· RUICKBIE, Leo - The Impossible Zoo: An encyclopedia of fabulous beasts and mythical monsters, entry: “Licorne”, without numbers on the pages. London, UK: Hachette, 2016

[27] The following works, despite older, are considered to be very important for this theme, since there are not many specialized references published recently: Singer, Isidore - The Jewish Encyclopedia. A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Tomes to the Present Day, v. XII. New York City, New York, USA and London, UK: Funk and Wagnalls, 1903, entry: “Unicorn”, p. 344 (HIRSCH, Emil; CASANOWICZ, Immanuel)· GODBEY, Allen - “The Unicorn in the Old Testament”. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 56/3 (1939), pp. 256-296

[28] GRAVES, Raphael; PATAI, Robert - Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis. New York City, New York, USA: Rosetta Books, 2014, Chapter 7 (unnumbered)

[29] Only two translated versions of the Old Testament were selected. Probably, if we chose to present other official ecclesiastical and university translation collections, we would find additional references to the unicorn in whatever form. A typical example is the following two cases of translation: a) Psalm of David 78.69: “[69] And he built his sanctuary as of unicorns, in the land which he founded for ever” (Douay-Rheims Catholic Bible/DRA. American Edition Version), and b) Psalm of David 78.69: “[69] And he as a unicorn built his holy place; in the land, which he founded into worlds. (And he built his holy place like his home in heaven/And he built his holy place as high as the heavens; and he founded it like the earth, to last forever)” (by John Wycliffe Bible/WYC)

[30] STRZYGOWSKI, Josef - Der Bilderkreis Des Griechischen Physiologus, Des Kosmas Indikopleustes Und Oktateuch: Nach Handschriften Der Bibliothek Zu Smyrna: Mit 40 Lichtdrucktafeln Und 3 Abbildungen Im Texte. Groningen: Bouma’s Boekhuis, 1969, pp. 28-29

[31] STRZYGOWSKI, Josef - Der Bilderkreis Des Griechischen Physiologus, Des Kosmas Indikopleustes Und Oktateuch: Nach Handschriften Der Bibliothek Zu Smyrna…, pl. XII

[32] ΠΡΟΒΑΤΆΚΗΣ, Θωμάς - Ο διάβολος εις την βυζαντινήν τέχνην…, pp. 174-175. The English translation of the inscription was made by the author of the present study

[33] WEITZMANN, Kurt - Das Evangelion Im Skevophylakion Zu Lawra [Seminarium Kondakovianum VIII]. Praha: Institut Kondakov, 1936, p. 88 (note 22); MINER, Dorothy Eugenia - “The ‘Monastic’ Psalter of the Walters Art Gallery”. in Weitzmann, Kurt (ed.) - Late Classical and Medieval Studies in honor of Albert Mathias Friend, Jr. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press, 1955, p. 232 (note 5), p. 243 (note 36); VILLETTE, Jeanne - La résurrection du Christ dans l’art chrétien du Iie au VIIe siècle. Paris: Henri Laurens, 1957, pp. 16-17, 111; ΠΕΛΕΚΑΝΊΔΗΣ, Στυλιανός - Οι Θησαυροί του Αγίου Όρους, Σειρά Α΄. Εικονογραφημένα Χειρόγραφα, παραστάσεις - επίτιτλα - αρχικά γράμματα, Μ. Μεγίστης Λαύρας, Μ. Παντοκράτορος, Μ. Δοχειαρίου, Μ. Καρακάλου, Μ. Φιλοθέου, Μ. Αγίου Παύλου, τ. Γ΄ (Αθήναι: Πατριαρχικό Ίδρυμα Πατερικών Μελετών, Εκδοτική Αθηνών, 1979), pp. 265, 275; WEITZMANΝ, Kurt - Die Byzantinische Buchmalerei Des 9. Und 10. Jahrhunderts. Wien: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996, pp. 24, 54-57, pl. 352-364; ΧΑΛΚΙΑ, Eυγενία - Φανταστικά & Απόκοσμα. Ημερολόγιο 2012. Αθήνα: Βυζαντινό και Χριστιανικό Μουσείο Αθηνών, Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Τουρισμού, 2012, p. 67

[34] CARMODY, Francis - Physiologus, The Very Ancient Book of Beasts, Plants and Stones. San Francisco, California, USA: The Book Club of California, 1953 (English translation with a plethora of commentaries); STRZYGOWSKI, Josef - Der Bilderkreis Des Griechischen Physiologus, Des Kosmas Indikopleustes Und Oktateuch: Nach Handschriften Der Bibliothek Zu Smyrna…, pp. 28-30; MERMIER, Guy - “The Romanian Bestiary: An English Translation and Commentary on the Ancient Physiologus Tradition”. Mediterranean Studies 13 (2004), pp. 17-55; ZUCKER, Arnaud - Physiologos: le bestiaire des bestiaries. Grenoble: Editions Jérôme Millon, 2004 (French revised translation with an abundant modern commentaries)

[35] AAVITSLAND, Kristin Bliksrud - Imagining the Human Condition in Medieval Rome: The Cistercian fresco cycle at Abbazia delle Tre Fontane. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2012, pp. 107-135, with interesting miniatures and frescoes of the western world (e.g. Italian peninsula), in which we observe many variations of the parable of the Futile Life (and/or biblical episodes, such as the Crucifixion)

[36] For more information about this symbol-iconographical motif in Hebrew-Christian worldview and general ideology, with partial comparisons from other religious systems through the presentation of primary sources and related archaeological finds, see indicatively: COOK, Roger - The tree of title: Image for the cosmos. New York City, New York, USA: Thames and Hudson, 1995; BUCCI, Giovanna - L'albero Della Vita Nei Mosaici Pavimentali Del Vicino Oriente. Bologna: University Press, 2001; METTINGER, Tryggve - The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2-3. Winona Lake, Indiana, USA: Eisenbrauns, 2007, mainly. pp. 5-11; ΤΣΙΡΈΛΗ, Ευλαμπία - Το Ιερό Δέντρο. Οι μύθοι και συμβολισμοί του. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εκδόσεις Δαίδαλος, 2014, mainly pp. 72-121

[37] See references above about the “Tree of Life”

[38] ȘTEFĂNESCU, Ioan - “Le Roman de Barlaam et Ioasaph Illustré en peinture”. Byzantion 7 (1932), pp. 367-368, fasc. 2. The novel has been known in Moldova since the 14th century from the southern Slavic manuscripts, but they are not illustrated

[39] ΣΩΤΗΡΊΟΥ, Γεώργιος; ΣΩΤΗΡΊΟΥ, Mαρία - Η βασιλική του Αγίου Δημητρίου Θεσσαλονίκης. Αθήναι: H εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία, 1952, v. 1, pp. 211-212 και v. 2, pl. 81α· ΣΩΤΗΡΊΟΥ, Γεώργιος - “Η γλυκύτης τού κόσμου”. Ημερολόγιον τής Μεγάλης Ελλάδος 8 (1929), pp. 111-116· ΞΥΓΓΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ, Ανδρέας - Σχεδίασμα ιστορίας της θρησκευτικής ζωγραφικής…, pp. 71-72; ΜΠΑΚΙΡΤΖΉΣ, Χαράλαμπος - Η βασιλική του Αγίου Δημητρίου. Θεσσαλονίκη: Εταιρεία Μακεδονικών Σπουδών, 1972, p. 64· ΚΑΖΑΜΊΑ, Μαρία - Μνημειακή Τοπογραφία της Χριστιανικής Θεσσαλονίκης…, p. 316; ΣΑΜΠΑΝΊΚΟΥ, Εύη - Η εικονογράφηση της σκηνής του Μαινόμενου Μονοκέρωτος…, pp. 137-138, p. 152, fig. 9 - sk. 2

[40] ΣΩΤΗΡΊΟΥ, Γεώργιος; ΣΩΤΗΡΊΟΥ, Mαρία - Η βασιλική του Αγίου Δημητρίου…, pp. 211-212

[41] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 1, p. 67

[42] NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie der - L' illustration du roman…, v. 1, p. 67

[43] MUÑOZ, Antonio - “Le representazioni alle goriche della vita nell’artebizantina”. L’Arte VII (1904), pp. 130-145