Introduction1

From the time of its beginnings in eleventh-century Jerusalem and its recognition as an order of the church by Pope Paschal II in 1113, the main purpose of the Hospital of St John was to care for the sick poor visiting Jerusalem. By the mid 1120s, however, partly in imitation of the Templars, the order was already beginning to assume military functions and to attract knights into its brotherhood. The order’s military activities soon extended beyond merely protecting its own property or providing sergeant service, as some other ecclesiastical institutions continued to do2. Instead, like the Templars, the order began to play an active part in the defence of the kingdom of Jerusalem and of the neighbouring Christian states to the north. In 1136, King Fulk granted the Hospital the newly built castle of Bayt Jibrīn, one of a ring of castles encircling Muslim-held Ascalon. In due course, the Hospitallers developed a network of greater and lesser fortified centres, fulfilling both military and administrative functions.

This paper is concerned with the building works associated with the Hospitallers’ military activities. As a result of the integrated functional organization of the order, however, it is often hard to draw a clear distinction between military and non-military buildings, or even to make a rigid functional classification of them. A castle, for example, might serve a number of military functions, from protecting travellers on the highway to serving as a garrison for troops and contributing to the general defence of the realm; but castles could also - and usually did - serve in other ways as secure centres for administering estates and collecting revenues to support the Hospital’s charitable works, for encouraging Frankish and indigenous Christian settlement of the surrounding lands, and (more especially in the north) for exercising lordship and the administration of justice. Below them in the settlement hierarchy were numbers of smaller fortified towers and other buildings established in agricultural villages or protecting mills, sugar factories or other rural installations. The castles were normally commanded by castellans, who also acted as conventual bailiffs, administering the order’s estates in the region; but exactly how the lower-order sites were managed and who lived in them is often not at all clear. Some appear to have been managed by brother knights, who appear in charters designated by the place where they were stationed; but in other cases it is possible that the occupiers would have been secular estate managers or stewards. The late Jonathan Riley-Smith calculated that at one time or another the Hospitallers would have held 56 strongpoints in Syria and Palestine, 11 of them only for short periods. In 1180, they may have been holding 25, and in 1244 perhaps 29, though most of these would have been relatively small3.

Contributions to town defence

In addition to the contribution that the Hospitallers made to the defence of the kingdom through the castles and centres that they managed on their own account, they also contributed to the defence of cities and in some cases castles held by other parties4.

In Jerusalem there are a number of indications that, like the Templars, the Hospitallers may have held a sector of the walls to maintain and defend. A rental of c.1157-1163, for example, includes an item of half a bezant paid annually by a woman, perhaps an anchoress, living inside the city wall in the Belcaire district on Mount Sion in the south-western part of the city5. In 1178, the Hospital possessed two houses next to the same wall near the ‘new gate’ leading to the church of Mount Sion.6 William of Tyre also records that after part of the city walls collapsed in 1178, the secular and ecclesiastical authorities agreed to allocate a certain amount of money each year for repairs7. This may account for the mention in a contemporary account of the siege of August 1187 of a “new tower, which had been built by the brothers of the Hospital”8.

In 1152 Maurice, lord of Montreal, granted the Hospital various rights and properties in Transjordan, and in Karak “a certain tower which is to the left as one enters the gate of the castle, and the barbican that is between the two walls extending from that tower as far as the tower of St Mary”9. It has previously been suggested that the barbican in question might perhaps have been a predecessor of the Mamluk lower ward on the western side of the castle, in which Paul Deschamps claimed to have detected some traces of earlier Frankish work10. A much likelier explanation, however, and one that tallies more convincingly with the topographical indications, is that the grant concerned the castle’s north-eastern tower and a double wall that ran south from it up to a tower adjoining the east end of the castle chapel (Fig. 1)11. Like the church of St Mary in al-Shawbak (Montreal), whose entitlement to tithes within the lordship is mentioned in the same document, this chapel would most likely have been served by canons of the Templum Domini, who appear to have had charge of the Latin ecclesiastical establishment in the lordship before the appointment of a bishop of Karak in 116712. A canon of the Templum Domini, Assenard, appears among the witnesses to the charter and, although the chaplain, Reinard, who was responsible for drafting it, is not similarly identified, it seems likely that he too was a canon and that the tower of St Mary represented the canons’ residence next to the chapel of the same dedication. Maurice’s grant was reconfirmed in 1177 by Renaud de Châtillon, lord of Montreal and Hebron, with the words, “in Karak (Petrac) a house (domus) with its appurtenances (pertinentia), as was given to the Hospital [by Maurice]”, suggesting that the arrangement with the Hospitallers was still in operation at that time13. The unstated implication of both charters is that the grantors’ expectation was that the Hospitallers would play their part in maintaining and defending the parts of the castle entrusted to them.

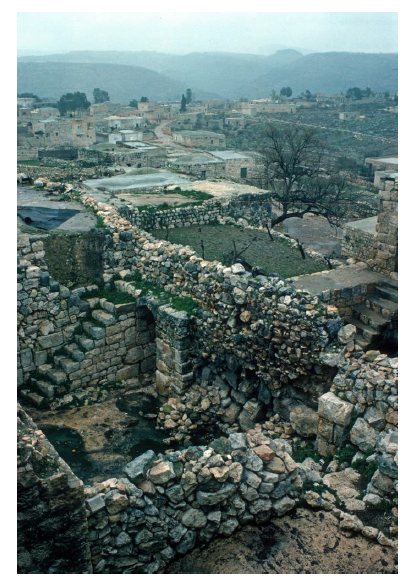

Fig. 1 Karak Castle: view looking N along the E wall. The Hospitallers’ barbican would have extended from near the tower in the centre of the wall to the now largely demolished NE corner-tower beyond it (© DP 2017).

In 1157, Humphrey II of Toron (Tibnīn) granted the Hospitallers half of the town of Bāniyās, which had formerly been part of the fief of Walter of Beirut14. According to William of Tyre, Humphrey’s reason was that he was unable to defend Bāniyās without assistance. The terms were that the Hospitallers were to have half of the city and its dependencies (civitas et suburbani) in return for bearing half the expense of defending it. On 26 April, however, as the relief convoy and its escort of knights and footsoldiers approached the city, they fell into an ambush prepared by Nūr al-Dīn’s brother, Nuṣrat al-Dīn Amīr-Mīrān. Most of the escort were killed or taken prisoner and all the provisions lost. Following this the Hospitallers withdrew from their agreement with the constable15. The city was attacked twice more by Nūr al-Dīn the same year before falling to him in 116416. Humphrey of Toron’s initial grant had also included half of Castellum Novum, or Hūnīn, presumably on the same terms;17 but this arrangement also seems to have been abandoned when the Hospitallers gave up Bāniyās, as there is no further mention of it.

In 1162, the Hospitallers received from Gerald, lord of Sidon, two gates in the wall and fore-wall of Sidon respectively and the entire fore-wall from Baldwin’s Tower to the Sea Tower18. This grant probably comprised the entire southern wall of the city between the Land Castle (Fig. 2) and the sea, along with the gate and barbican facing Tyre, which are also referred to in other charters19. The grant was confirmed by Balian, lord of Sidon, in May 123720. In 1262, however, two years after the sale of the lordship of Sidon to the Templars, the Hospital passed all its possessions in the city to the Templars21.

Fig. 2 Sidon: the Land Castle, occupying the site of the Roman theatre. This was probably Baldwin’s Tower, which marked the E end of the Hospitallers’ barbican in 1162 (© DP 1998).

In the 12th century the Hospitallers also seem to have contributed to the defence of Ascalon, where they gave their name to a tower which Bahāʾ al-Dīn describes as “a vast tower, overlooking the sea, like an impregnable fortress”. This was so strongly built that when Saladin ordered its demolition in September 1191, it had to be packed with timber and left to burn for over two days before pickaxes would have any effect on it22. This tower may have formed part of a sector of the town walls that the Hospitallers had inherited from the Spanish order of Mountjoy at the time of the return of the head of that order, Roderic, to Aragon around 1180, before its amalgamation with the hospital of the Holy Redeemer in Teruel in 118823. The sector had been granted to the order of Mountjoy between Christmas 1176 and 30 June 1177 by Sibylla, countess of Ascalon, no doubt on the understanding that the order would maintain and defend it. The sector included: “the Tower of the Maidens in the town of Ascalon, and the garden below the tower, and two other towers on the walls of the same town between the previously mentioned tower and the church of St Mary, and another one towards the sea on the other side of the Tower of the Maidens”24. This grant was confirmed in similar terms by Pope Alexander III on 15 May 118025. The stretch of wall concerned would therefore have comprised four mural towers and the intervening curtain walls between the sea and the unlocated church of St Mary. It probably lay on the south side of the city, with its westernmost tower close to and overlooking the sea26.

In 1194, Count Henry of Champagne granted the Hospitallers the possession of an entire quarter in Jaffa between the town wall facing the sea on the north and west and the castle on the south, including two towers - one of them named the Tower of the Hospital - on the town wall and right of access to the harbour27. In 1207/8 and 1240 there is mention of a bailiff of Jaffa, whom Riley-Smith suggests may have had charge of what remained of the 12th century bailiwick of Spina28. In Tyre, sometime between 1198 and 1205, Aimery of Lusignan and Queen Isabella also granted the Hospitallers a gate in the city wall behind their house. Although this faced south on to the sea and was not therefore part of the land wall, it must still have been of some potential economic or military significance, for in June 1270 the Hospital accepted a grant of the village of Maron (Marūn al-Raʾs) and other rights in return for agreeing to wall it up29.

During the 13th century, the Hospitallers made a significant contribution to the defence of the walls of Acre. In 1192 and 1194, King Guy and Henry of Champagne respectively had granted them a block of land for their new headquarters inside the north wall of the city, between the Tower of the Hospital beside Our Lady’s Gate on the east and St John’s Gate on the west, with permission to fortify the latter, though with a royal gatekeeper to control access in and out of it. The grant also included the barbican and outer wall in front of it30. Following the enclosure of the Montmusard suburb by a double wall by 121231, this part of the old north wall would have lost much of its defensive importance; even so, in 1235, the Hospitallers acquired more of it to the west, including the New Gate, which had formerly been called the Tower of the Prison32. In 1193, however, Henry of Champagne had also granted them part of the east wall, from the Gate of Geoffrey le Tor northwards to the gate-tower of St Nicolas, including the outer wall, the barbican or lists between the two walls, and land outside the outer wall33. Doubtless, like the Teutonic Order, who were given the sector north of this, they would have been expected to maintain and defend it34. By 1217, however, following the construction of the new walls around Montmusard, the Hospitallers appear to have relinquished this sector to the Germans and were granted instead the southern sector of the wall of Montmusard between the Gate of Evil Step (Malpas) and the Gate of St Antony. It was through this gate and the Hospitallers’ garden in front of it that Riccardo Filanghieri secretly entered and left the city in 124235. This sector, marked custodia hospitalis or hospitalariorum on the Vesconte maps of Acre (c.1320), was defended during the Mamluk siege of 1291 by the Hospitallers and the knights of the associated Spanish confraternity of St James36.

Castles

According to William of Tyre, Bayt Jibrīn (pg 140.112) was built by King Fulk as the first of a planned ring of castles to contain Muslim raiding from Ascalon. It was sited in the ruined city of Eleutheropolis, which the Franks mistakenly identified as Beer-sheba37, and initially consisted of “a fortress (presidium) strongly fortified with an insuperable wall, outworks and a ditch as well as towers”38. When it was finished, Fulk granted the castle to the Hospital. In his confirmation of this grant between September and December 1136 he also added ten casalia given by Hugh (II), the castellan of Hebron, and another four granted directly by the king himself, all of them located in the royal domain of Hebron39. Around 1150, Usāma ibn Munqidh took part in an Ascalonite raid on Bayt Jibrīn, where the Egyptians succeeded in burning the Franks’ newly harvested grain but were beaten off by other Franks assembling from nearby fortresses40. Egyptian raiding did not end with the fall of Ascalon in 1153 and another attack is recorded in 115841. Civilians were evidently already settling in Bayt Jibrīn before 1153, and by 1160 they had been granted a charte de peuplement by the Hospitaller master, Raymond du Puy, which was reconfirmed in 1168 and again after 117742. An un-named castellan is mentioned in 115543, another named Aimo in 116844, and a third, Garnier of Nāblus, between 1173 and 117545. Although in theory Bayt Jibrīn was ceded to the Franks between 1240 and 124446, there is little evidence for the castle’s reoccupation or for any revival of its castellany47.

Excavation of the castle from the 1980s onwards, albeit still mostly unpublished, has revealed that the first phase consisted of a quadriburgium, some 50 m square with solid turrets at the corners (Fig. 3), built over the remains of a Roman bath building. This lay just inside a corner of the late Roman city wall, which formed the north and western sides of an outer enceinte measuring some 170 m east-west by 125 m north-south. It also enclosed the remains of the Roman amphitheatre, which was progressively dismantled for building material as the castle took shape. In a secondary period outer walls, towers and moats were added and the interior was divided into two. In a final Frankish phase, which the excavators date after 1153, the military character of the castle was to some extent compromised by the construction of dwellings, stables and store-rooms in the outer ward and the erection of a conventual church, which doubtless also served the needs of the parish. This was built against the south side of the inner ward and was linked to its refectory at ground level and most probably to the dormitory at first-floor level48.

Fig. 3 Bayt Jibrīn (Bethgibelin): the W side of the four-towered castle granted by King Fulk to the Hospital in 1136 (© DP 2002).

The site of the castle of Belmont corresponds with that of the ruined village of Ṣūba (pg 162.132), west of Jerusalem, which from the 12th century onwards was identified (incorrectly) with biblical Modein, the burial place of the Maccabees. It lay within an estate in the terra Emaus, centred on Abu Ghosh (Qaryat al-ʿInab, pg 160.134), which the Hospitallers identified as biblical Emmaus and already possessed by 1141, when they reached an agreement with the patriarch over the payment of tithes. William de Bellomonte, who assisted the preceptor and treasurer of the Hospital in a financial transaction in Jerusalem in 1157, would probably have been the castellan49; An un-named castellan is also referred to in 116950; and in April 1186 the castellan was Bernard de Asinaria51; who probably succeeded Brother Bartholomew, who is mentioned as bajulus Emaus in February of the same year52. In 1187, the castle fell to Saladin, who is alleged to have ordered its demolition in 119153. Apart from a cache of three English short-cross pennies (1180×1247)54, which possibly reached Belmont during the Third Crusade or when the area returned to Frankish control between 1229 and 1244, there is no evidence of Frankish reoccupation and until 1948 the site was occupied by a village55.

Excavation by the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem between 1986 and 1989 revealed that the earliest phase of the castle consisted of a maison forte, or manor house, constructed on the summit of the hill and remarkably similar in plan to another, also Hospitaller, standing in the valley below it at Aqua Bella (Khirbat ʿIqbalā, pg 162.133) (Fig. 4). It seems likely that the builders of these and another known as Shaykh Ibrahim (pg 162.132), lying a hundred metres south of the castle, were previous tenants rather than the Hospitallers themselves. At any rate, whereas the manor house at Aqua Bella was subsequently converted into what appears to have been a monastic infirmary, by the insertion of an apse and chancel screen into its hall, the one at Belmont was instead developed into a castle by adding a polygonal outer enceinte with an external talus and gatehouse on the south-east, enclosing vaulted ranges including stables56.

Fig. 4 Aqua Bella (Kh. ‘Iqbala): a Frankish manor house, converted into a monastic infirmary by the Hospitallers after c.1140 (© DP 2013).

The third major castle to be established by the Hospitallers in the kingdom of Jerusalem was Belvoir (pg 199.222). Walter of Tiberias’s confirmation of the sale of this to the Hospital for 1,400 bezants by Ivo Velos, issued in April 1168, described it as castrum de Coquet, quod vulgariter Belvear nuncupatur, cum suis divisis et pertinentiis57, making it clear that a castle of some kind already existed. The concentric castle that the Hospitallers built over the next twenty years is discussed elsewhere in this volume, so there is no need to say much about it here. After the castle’s surrender to Saladin on 5 January 118958, however, it was repaired and continued to be garrisoned for another thirty years until 1219, when it was demolished by al-Muʿaẓẓam ʿĪsā59. Although the area was returned to Frankish hands between 1241 and 1263 and the Hospital reached an agreement with the archbishop of Nazareth over its tithes on 25 October 125960, there does not appear to be any evidence to indicate that it was ever reoccupied or refortified. Indeed, the late 13th century writer Ibn Shaddād says explicitly that it was not61.

The earliest castellan of Belvoir to be mentioned, in 1173, is Oldinus (Rollant)62, who in 1165-66 had been preceptor of Spina63. He was followed by Alebaudus, castellanus Belviderii in 118464, and Monterius, castellanus de Belveeir in April 118565. Among the witnesses to the sale of Margat castle to the Hospital on 1 February 1186 was Brother Hermann, a former castellan of Crac des Chevaliers66, who is described in the charter as tunc temporis Betanhie bajulus67. It is usually assumed that this official was commander or bailiff of Bethany, between Jerusalem and Jericho68. From 1138, however, Bethany had been in the possession of the Benedictine nuns of St Lazarus and it is difficult to see how a Hospitaller commandery could have been accommodated there at the same time69. Bayt Ḥanīnā, another village near Jerusalem that is also referred to as Betania, seems no more plausible, as it had been granted to the nearby Premonstratensian abbey of St Samuel on Mount Joy, also in the reign of Fulk (1131-43)70. A likelier identification is Baysān (Bet Sheʿan, pg 197.211), ancient Scythopolis and the former metropolitan see of Galilee, which is referred to in Frankish sources variously as Bethsan, Baisan, Beisan and Bezan, but also as Bethan and Bethania. In 1103, for example, Pope Paschal II confirmed to the abbey of Mount Tabor four villages in terra Bettanie (or Bethanie)71. Gustav Beyer took this to refer to Batanaea, the ancient name for the region east of the Jawlān in Transjordan, which in medieval times gave its name to al-Bathaniyya, a district of Damascus72. Two or possibly three of the four listed villages, however, appear to have been located west of the Jordan between Tiberias and Baysān, albeit not necessarily in what later became the lordship of Baysān itself73. In 1173, King Amalric also granted two villages in partibus Bethan, Shaykh Riḥāb (Rehap, pg 197.206) and Bardala (Ardelle, pg 195.199), along with their villani and sugar plantations, to the German Hospital in Jerusalem74. These also lay on the west bank of the Jordan, just south of Baysān. In 1186, following the death of Adam of Baysān leaving only minors as heirs, the lordship would have been in the wardship of Hugh, son of Hugh lord of Byblos (Gibelin), who in November 1179 had leased it for seven years to Joscelin, former count of Edessa, for 600 bezants annually75. In 1183, however, the town of Baysān, which William of Tyre describes as no more than a castle and small township surrounded by marshes, was abandoned by its few remaining inhabitants just before being sacked by Saladin76. There is no evidence that the Hospitallers subsequently had any role in administering the lordship or even that they themselves possessed any land in Baysān itself, although they had acquired al-Zarraʿa (Assera, Adera, pg 199.203) within the lordship in 114977. It seems quite possible, however, that just as the bailiff of Emmaus, named in the same document, may be identified as the castellan of Belmont, the bailiff of Baysān was none other than the castellan of Belvoir, in both cases a more familiar biblical name being substituted for one that was less easily recognizable.

Another castle that the Hospitallers held in the kingdom of Jerusalem before 1187 was that known as the Castle of St Job, just south of Jinīn. This was also referred to in 1156 as Castellum Beleismum and may be identified with Khirbat Balʿāma (biblical Jibleam, Belemōth, pg 177.205), situated at the border of the lordship of Nāblus with the principality of Galilee, where the road south from Jinīn to Sebaste entered the Sahl ‘Arrāba, known to medieval writers as the Plain of Dothan78. It was here that Guy of Lusignan and Raymond of Tripoli were reconciled in 1187, following the disastrous battle with the Muslims at the Springs of the Cresson. The account in the Chronique d’Ernoul specifies that this castle belonged to the Hospitallers.79 The remains, sited on a largely natural tell to the west of the road, consist of a tower some 8 m square standing in the south wall of a rectangular enclosure, some 60 m east-west by 40 m north-south, with rows of rooms along the eastern and western sides. On the east side of the mound beside the road remains of a chapel stand over a barrel-vault some 3 m wide, leading to a spring known as that of St Job (Biʾir al-Sinjīb)80. There is no record of any estate or castellan attached to the castle, though it is possible that it functioned merely a road-station for pilgrims and other travellers, administered from the order’s hospital in Nāblus81.

Lesser sites, towers and maisons fortes

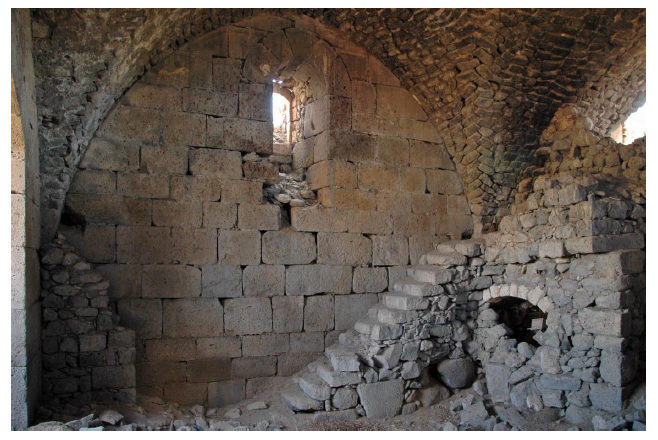

As already indicated, the rural properties of the Hospital were generally grouped into estates or bailiwicks, administered by officials, who are referred to variously as bailiffs, commanders, preceptors or - if based in a castle - castellans. Among the properties forming part of the estate granted to the Hospital along with the castle of Bayt Jibrīn in 1136 was Bayt Sūr (Bethsura), between Hebron and Bethlehem, where there are still remains of a Frankish tower (Burj al-Sūr, pg 159.110)82. Sites dependent on Belmont Castle include the church and estate centre at Abu Ghosh (Qaryat al-ʿInāb, Emmaus, pg 160.134) and the manor house or infirmary building at Aqua Bella (Khirbat ʿIqbalā, pg 162.133), neither of which could be described as primarily a military work, despite their basic defensibility83. The fortified site of al-Taiyiba (medieval ʿAfarbalā, Forbelet, pg 174.151), however, which seems to have depended on Belvoir Castle and whose remains include a tower some 26 m square (Fig. 5), has a more obviously defensive character84. William of Tyre described the place in 1182-3 simply as a vicus or locus85. but Arabic accounts refer to it as a ḥiṣn or fortress86. Although recent archaeological work in the vicinity of the tower has done much to extend our understanding of the settlement from the Byzantine period to late Ottoman times, the precise nature and extent of the Frankish fortifications has still to be determined87.

Fig. 5 Al-Taiyiba (medieval ʿAfarbalā, Forbelet): inside face of the S wall of the Hospitaller tower (© DP 2015).

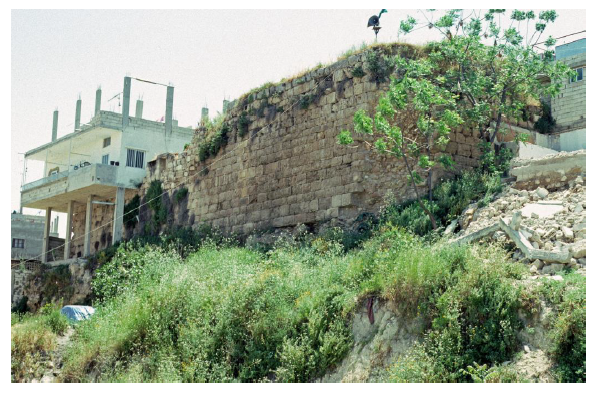

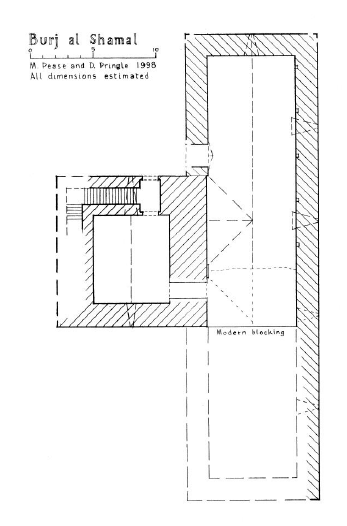

Around Jerusalem Hospitaller estates would have been managed by the grand commander and around Tyre and Acre by their respective regional commanders88. Near Jerusalem, such properties would have included the village of Bayt Ṣafafa (Bethafava, pg 160.128), which Baldwin I gave to the Hospital sometime before September 1110. Here there still stand the remains of a two-storey tower, some 18.2 by 13.7 m, at one time associated with a rectangluar enclosure wall with an outer talus, enclosing vaulted structures89. Just outside Tyre, the village of Burj al-Shamālī (pg 172.126) contains a tower linked to a barrel-vault (Figs. 6-7), which may perhaps be la Tor de l’Ospital that was among the ten casalia conceded to Margaret, lady of Tyre, by Sultan al-Manṣūr Qalāwūn in 128590. Sites in the territory of Acre would have included the mill of Kurdāna, of which only fragmentary remains survive (pg 1610.2501)91, and the estate centre and sugar mill of Manawāt (Ḥorvat Manot, pg 164.271)92, whose fief the Hospitallers purchased from Nicolas, grandson of Sait the Scribe, for 1,400 bezants in September 123193, having previously acquired the rights there belonging to John of Brienne and Maria la Marquise in April 121294, and those of Beatrice of Hennenberg, daughter of Joscelin III of Courtenay, in January 121895.

In the twelfth century, the Hospitallers possessed some houses in Caesarea and very likely a church96, but it is uncertain whether their extensive land holdings in the lordship were administered from there or from outlying casalia97. One possible location for a commandery in the south of the lordship was Qalansuwa (Calansue, pg 148.187), a casale granted to the Hospital by the knight Geoffrey of Flujeac in April 112898. However, it appears that the lords of Caesarea retained control of the place, since a viscount, Peter de Fossato, and a dominus Paganus de Calenzun are recorded in 116699, and Frankish settlers were living there during the time when Raymond du Puy was master (1125-58)100. Potential Hospitaller commanders of Qalansuwa include Gerard, or Gerald (1131-35), and Simon (1207/8)101. The architectural remains include an early tower, a large eight-bayed two-storey hall building (now the mosque) (Fig. 8) and various vaults set around a central open space. It is difficult to tell, however, which of these buildings belonged to the Hospitallers and which to the lords of Caesarea102.

Fig. 8 Qalansuwa: two-storey Frankish hall, from the SE. (© DP during survey with Peter E. Leach in 1983).

In the 12th century, the lords of Caesarea also had a viscount and dragoman in Qāqūn (pg 149.196), where a castle already existed by May 1123103. By September 1110, the Hospitallers possessed lands and villeins there and when Walter Garnier issued a confirmation of all their possessions in the lordship in September 1131 they also had some houses. The mention among the witneses to the latter document of a Hospitaller brother named Aldebrandus Chaco suggests that by that time they may also have been using the village as an administrative centre104. The Hospitallers continued to acquire properties in the area and by 1189 were leasing from the abbey of St Mary Latin two other villages with existing small castles, Madd al-Dayr (Montdidier, pg 141.196) and Burj al-Aḥmar (Turris Rubea, Turris Latinae, pg 145.191), as well as further land in Qāqūn. During the period of Saladin’s conquest and the Third Crusade, these properties came into the hands of the Templars, but although the abbey undertook to restore them to the Hospital in May 1236, it appears that the lease was not finally reinstated until August 1248105. Both castles consisted of a tower set within an enclosure, though it remains uncertain what, if anything, the Hospitallers themselves may have contributed to them106.

In the northern part of the lordship of Caesarea, the Umayyad fort at Kafar Lām (Cafarlet, Ha-Bonim, pg 140.226) was briefly in Hospitaller possession in the 13th century, being pledged to the order in 1213 and finally sold to it in 1232; but in 1255 it was acquired by the Templars and would have been taken by Baybars a decade later. Excavations in 1999 indicate that in the Frankish period the fort’s interior was occupied by village houses but that a small chapel was built against the outer face of the west wall sometime in the 13th century, though who was responsible for it is unclear107. To the south of this, Burj al-Maliḥ (al-Mallūḥa, Turris Salinarum, pg 141.216), which Hugh, lord of Caesarea had granted the Hospital between c.1154 and 1168, was destroyed by Baybars in 1265108. There was another tower at Khirbat al-Mazraʿa (le Meseraa, casale Rogerii de Chasteillon, pg 143.222), which John Lalaman, lord of Caesarea, sold to the Hospitallers in 1255; but this village would have been theirs for no more than a decade109.

Riley-Smith suggested Qalqīliyya (pg 146.177), in the lordship of Arsūf, as another possible location for a small Hospitaller castle110; but there are no structural remains of the Frankish period nor any evidence that the Hospital even owned property there. Sometime before 1168, Bartholomew, the lord of the town or village (ville dominus), granted some property in Qalqīliyya to the Holy Sepulchre111; but Geoffrey (Gaufridus) de Qualquelia, who witnessed a Hospitaller charter in April 1168, appears to have been a vassal of John, lord of Arsūf, rather than a member of the order112, as was his descendent John de Cauquelie, who was listed as such in 1241 and 1261113. On the other hand, Brother Hugh de Calcalia, who is mentioned in witness lists between 1181 and 1185114, was certainly a Hospitaller; but in view of the lack of any other Hospitaller connection with Qalqīliyya, his name more likely reflects his family origins than an administrative position.

To the south of the lordship of Arsūf, the Hospitallers had another commandery at Spina, administering their estates in the northern part of the county of Jaffa and the lordship of Mirabel. A preceptor of Spina named Oldinus Rollant witnessed grants by Baldwin of Mirabel to the Hospital in 1165 and 1166; by 1173 he was castellan of Belvoir115. Brother Raynald, bajulus Spine, witnessed Bohemond III of Antioch’s ratification of the granting of Valania and Margat to the Hospital on 1 February 1186116. The precise location of Spina is uncertain. The only clue is a charter of 25 January 1158/59, by which Hugh of Ibelin ceded to the Hospital some land located between the mills of Mirabel and the land of Spina117. Gustav Beyer identified these mills with those whose remains still survive at al-Mirr (Maḥmūdiyya, pg 142.168)118 on the Nahr al-ʿAwjāʾ (River Yarqon) below Raʾs al-ʿAyn and suggested three possibile identifications for Spina itself: Fajja (Fijja, pg 140.166), Nabī Thārī (pg 143.163) and Khirbat Shaʿīra (pg 140.164)119. None of these names, however, appears to have any connection with the word spina, meaning ‘thorn’ or ‘thistle’, the Arabic equivalent of which, shawk120, is found in place names such as Shuwayka (pg 153.193), a village near Ṭulkarm121. The medieval name for Nabī Thārī is unknown, the present Arabic one evidently being derived from a maqām built on the site in late Mamluk to early Ottoman times122. Excavations around this between 1996 and 2000, however, revealed extensive remains of buildings of the Abbasid, Frankish and Mamluk periods123. This evidence, as well as its situation on the main road between Raʾs al-ʿAyn and Lydda, make Nabī Thārī a prime candidate to identify with Spina, though conclusive proof is still lacking124.

Whatever the exact location of Spina may have been, its dependencies would doubtless have also included the mills further down the ʿAwjāʾ at al-Ḥaddar. These were known as the Mills of the Three Bridges (pg 134.168), because it was there that the Jaffa to Jaljūliyya and Arsūf to Raʾs al-ʿAyn roads crossed the confluence of the ʿAwjāʾ with the Nahr Abū Lajja and Nahr al-Ashkar. The mills and the “island” between the rivers were granted to the Hospitallers by Hugh of Jaffa in 1133125; and in 1241, John III of Arsūf sold them the adjacent northern area lying within his lordship126. These mills remained in use until 1918, and some remains of them still survive127.

The village of Qūla (Chula, Cole, pg 145.160), south of Mirabel, was purchased by the Hospital from Hugh of Flanders for 3,000 bezants in September 1181128. A set of regulations drawn up soon afterwards for the operation of the Hospital in Jerusalem lists le casal Cole among six casalia, including ʿAbūd, specializing in producing foodstuffs for the sick129. The surviving remains in Qūla include part of a tower (17 × 12.8 m) and an adjacent barrel-vaulted building associated with a cistern130.

A confirmation of privileges granted to the Hospital by Pope Eugenius III in January 1153 includes a place called Belforte131. When the Hospitallers acquired the village of ʿAbūd (pg 156.158) from Baldwin of Mirabel in 1167, it was described as casale quod appellatur S. Mariae, contiguum territorium Bellifortis132. This has allowed Belforte to be identified with the present-day village of Dayr Abū Mashʿal (pg 156.156), where remains of a walled enclosure some 45 m square but of uncertain date were noted in the 19th century at the highest part of the site (Fig. 9)133. On 29 April 1166, Baldwin of Mirabel also confirmed his grant to the Hospitallers for their hospital in Nāblus of various properties and rights within his lordship, including the second tithes from Mirabel, Sūsiyya, Marescalcia (Dayr Abū Mashʿal?)134, Casreherre (Kafr al-Dīk?) and Rantiyya (Rentie, pg 142.161); however, although a Frankish-period vault or bawbariyya still survives in Rantiyya, it is unlikely to have belonged to the Hospitallers, as there is no evidence that they possessed any land there135. Riley-Smith plausibly suggests that in the 13th century what remained of the estates of Spina would have been administered by the commander of Jaffa136.

Fig. 9 Dayr Abū Mashʿal (Belforte): village and fortification, which belonged to the Hospital by 1153 (© DP 1980).

The final years of the Kingdom

In the final decades of the kingdom of Jerusalem the Hospitallers were sometimes granted entire castles and lordships that no-one else was able or prepared to take on. In April 1244, for example, they were handed the newly built castle in Ascalon by the emperor Frederick II’s bailiff, Thomas of Acerra. Construction of this had been started in the summer of 1240 by Tibald, king of Navarre and count of Champagne, and Hugh IV, duke of Burgundy, and was brought to completion by Richard, earl of Cornwall, in April 1241. According to Richard’s own account, it was built of ashlar reinforced with cut-up marble columns and included high towers and outworks, enclosed by a double wall and ditch. Archaeological research shows that it lay in the north-western corner of the city, with the town wall on the north and the sea cliffs on the west. Under the terms of the agreement, the Hospitallers were to do their best to hold and defend the castle, on the understanding that the emperor would reimburse their expenses, whether or not they were successful. As things turned out the castle was besieged by the Ayyubids from October 1246 and was taken by storm almost exactly a year later in October 1247. For the next ten years, the Hospitallers doggedly pursued their claim for compensation from the new count of Jaffa and Ascalon, John of Ibelin, but apparently without any success137.

Mount Tabor in Galilee had been ceded to the Franks in 1241 and was confirmed in Christian hands in 1255138. On 1 April 1255, Pope Alexander IV granted the Benedictine abbey and its estates to the Hospitallers, on the understanding that so long as peace held they would build there a fortress within ten years, garrisoned by forty knights139. The intention here was clearly to recommission the Ayyubid fortress that had been built around the abbey in 1212 and slighted by al-Muʿaẓẓam ʿĪsā in 1218140. By end of June 1255, Mount Tabor was already in the Hospitallers’ hands and their castellan, Jocelmus of Tornell, was taking formal possession of nearby villages141. There is no mention of any garrison, but if the castle had been built and garrisoned with a similar proportion of knights to other ranks to that applied by the Templars at Safad in 1260, the 40 knights stipulated by the pope would imply an intended total garrison of around 1,360, including some 24 sergeants, 40 turcopoliers, 240 archers, 656 workmen and 320 slaves or impressed workers142. In May 1256, three of the former monks of Mount Tabor wrote to Pope Alexander IV, commending to him the efforts that the Hospitallers were making and noting that, although the site had not yet been fortified, it was already garrisoned by a quantity of armed knights, as were some of its casalia, the divine offices were once again being celebrated there and every day it was being visited by pilgrims143. There is no evidence, however, that any of its fortifications were actually rebuilt before Baybars destroyed the church and monastery in April 1263144.

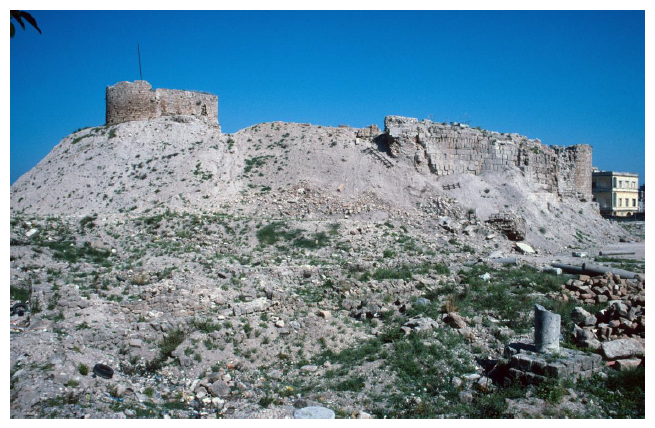

In 1261, Balian of Ibelin, lord of Arsūf, leased to the Hospital for an annual rent of 4,000 bezants the castle and city of Arsūf, as well as the part of the lordship directly dependent on it, including responsibility for the performance of knight service145. A list of the vassals who owed Balian service and what the Hospital was obliged to pay them was drawn up on 1 May 1261146. The castle dated initially from the 12th century and was sited on the cliff edge at the northern end of the site (Fig. 10); but its defences had been completely overhauled by John of Ibelin, lord of Arsūf, from 1241 onwards147. The new works included a twin-towered gatehouse with a portcullis and timber doors, which projected from the leading edge of a polygonal curtain wall with rounded mural towers, enclosing the earlier domestic part of the castle, including a new rib-vaulted first-floor chapel. The curtain was enclosed by an apron wall with rounded bastions rising from the bottom of a deep wide counterscarped ditch crossed by a timber bridge. When built in the 1240s and 1250s, this would have been a very up-to-date design by European standards148. The recent excavations by the late Israel Roll and Oren Tal have shown what preparations the Hospitallers made for the siege. They included adding a tower to the south-east corner of the town wall and contructing earthen ramparts supporting a 15 m wide fighting platform behind the south wall of the town149. In the castle the south-east tower was partly dismantled to allow easier access to the outer wall overlooking the moat and the chapel was reinforced, taluses being added to the two corners facing the courtyard. Other changes, such as modifications to the interior of the gatehouse and the adaptation of parts of the castle for food storage and cooking were concerned more with the domestic needs of the hugely augmented garrison than with improving its physical defensibility. The siege lasted from mid March to 29 April 1265, after which the castle was demolished150. The Hospitallers’ lease, however, was only finally terminated in 1269151. Thus was lost the Hospitallers’ last major castle in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and their last major house outside Acre and Tyre.

Bibliographical references

Printed Sources

“Annales de Terre Sainte”. In EDBURY, P.W. (ed.) - In “A New Text of the Annales de Terre Sainte”. In SHAGHRIR, I.; ELLENBLUM, R.; RILEY-SMITH, J. (eds.) - In Laudem Hierosolymitani: Studies in Crusades and Medieval Culture in Honour of Benjamin Z. Kedar. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007, pp. 145-161.

“Annales de Terre Sainte”. In RÖHRICHT, R.; RAYNAUD, G. (eds.) - Archives de l’Orient latin 2.2 (1884), pp. 427-461 (versions A and B).

“L’Estoire de Eracles empereur et la conqueste de la Terre d’Outremer”. In Recueil des historiens des croisades: Historiens occidentaux 1-2. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1844, 1859.

“La Continuation de Guillaume de Tyr (1184-1197)”. Ed. M.R. Morgan. In Documents relatifs à l’Histoire des Croisades. 14. Paris: Geuthner, for the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1982.

“Libellus de Expugnatione Terrae Sanctae”. Ed. J. Stevenson. In Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aeui Scriptores, or Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland in the Middle Ages (Rolls Series) 66. London, 1875, pp. 209-262.

ABŪ SHĀMĀ - “Le livre des deux jardins”. Ed. and trans. Barbier de Meynard. In Recueil des historiens des croisades: Historiens orientaux 4-5. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1879 and 1895.

Alexander IV - Les Registres d’Alexandre IV. Ed. C. Bourel de la Roncière et al., 3 vols (8 fascs). Paris : Fontemoing, 1902-1959.

AL-MAKĪN IBN AL-ʿAMĪD - “Chronique des Ayyoubides (602-658/1205-6-1259-60)”. Trans. A.-M. Eddé and F. Micheau. In Documents relatifs à l’Histoire des Croisades. 16. Paris: Geuthner, for the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1994.

AL-MAQRĪZĪ - A History of the Ayyūbid Sultans of Egypt. Trans. R.J.C. Broadhurst. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980.

AMBROISE - Estoire de la guerre sainte. A. AILES, A.; BARBER, M. (ed. and trans.) - The History of the Holy War. 2vols. (vol. 1: text; vol. 2: translation). Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2003.

BAHĀʾ AL-DĪN IBN SHADDĀD - “Al-Nawādir al-Sulṭaniyya wa’l-Maḥāsin al-Yūsufiyya”. In The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin. Trans. D.S. Richards. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002.

BRESC-BAUTIER, Geneviève (ed.) - Le Cartulaire du chapitre du Saint-Sépulcre de Jérusalem. Documents relatifs à l’Histoire des Croisades 15. Paris: P. Geuthner, 1984.

Cartulaire générale de l’ordre des Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem (1100-1310). 4 vols. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1894-1906.

Chronicon de Lanercost 1201-1346. Ed. J. Stevenson, Maitland Club, vol. 46. Edinburgh, 1839.

Chronique d’Ernoul et de Bernard le Trésorier. Ed. L. de Mas Latrie. Paris: Société de l’histoire de France, 1871.

Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaeualis. Turnhout: Brepols, 1966- .

De constructione castri Saphet, Construction et fonctions d’un château fort franc en Terre-Sainte. Ed. Robert B.C. Huygens. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company, 1981.

Die Urkunden der lateinischen Könige von Jerusalem = MGH Diplomata Regum Latinorum Hierosolymitanorum. Ed. H.E. Mayer, 4 vols. Hanover, 2010.

Documents relatifs à l’Histoire des Croisades. Paris, 1946- .

Hadashot Askheologiot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel (several volums since 1961; available since 2004 at https://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/about_eng.aspx).

IBN AL-ATHĪR - “al-Kāmil fī’l-taʾrīkh”. In The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athīr for the Crusading Period. 3 vols. Trans. D.S. Richards. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006-2008.

IBN AL-FURĀT - “Taʾrīkh al-Duwal wa’l-Mulūk”. In Ayyubids, Mamlukes and Crusaders. 2 vols. Ed. and trans. U. Lyons and M.C. Lyons Cambridge: Heffers, 1971.

IBN AL-QALĀNISĪ - “Dhayl Ta’rīkh Dimashq”. In The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades. Extracts trans. H.A.R. Gibb, London: Luzac, 1932.

IBN MUYASSAR - “Akhbar Miṣr (Annales d’Égypte)”. In Recueil des historiens des croisades: Historiens orientaux 3. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1884, pp. 461-473.

IBN SHADDĀD AL-HALIBĪ, ʿIzz al-Dīn - al-Aʿlaq al-Khaṭīra fī Dhikr Umarāʾ al-Shām wa’l-Jazīra, 2.2: Tārῑkh Lubnān, al-Urdunn wa-Filasṭīn. Ed. S. al-Dahhān. Damascus, 1962.

ʿIMĀD AL-DĪN AL-IṢFAHĀNĪ - “al-Fatḥ al-Qussī fī’l-Fatḥ al-Qudsī”. In Conquête de la Syrie et de la Palestine par Saladin. Trans. H. Massé. In Documents relatifs à l’Histoire des Croisades. 10. Paris: P. Geuthner, for the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1972.

Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi. Ed. W. Stubbs, in RS 38.1. London, 1864. Trans. H.J. Nicholson, Chronicle of the Third Crusade. Crusade Texts in Translation 1. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997.

JOHN OF IBELIN - Le Livre des Assises. Ed. P.W. Edbury. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

JOHN OF WÜRZBURG - Descriptio Locorum Terrae Sanctae. Ed. Robert B.C. Huygens, in Peregrinationes Tres, pp. 78-141. In Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis 139. Turnhout: Brepols, 1994.

MATTHEW PARIS - “Chronica Majora”. Ed. H.R. Luard. In Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aeui Scriptores, or Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland in the Middle Ages (Rolls Series) 57.1-7. London, 1872-83.

PHILIP OF NOVARA (Filippo da Novara) - Guerra di Federico II in Oriente (1223-1242). Ed. and Italian trans. S. Melani. Naples: Liguori, 1994.

Recueil des historiens des croisades: Historiens occidentaux. 5 vols. Paris : Imprimerie royale: Imprimerie impériale: Imprimerie nationale, 1844-1895.

Recueil des historiens des croisades: Historiens orientaux. 5 vols. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1872-1906.

Regesta Regni Hierosolymitani. Ed. R. Röhricht. Innsbruck: Libraria academica Wagneriana, 1893.

Regesta Regni Hierosolymitani: Additamentum. Ed. R. Röhricht. Innsbruck: Libraria academica Wagneriana, 1904.

Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aeui Scriptores, or Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland in the Middle Ages (Rolls Series). 99 vols. London, 1858-1897.

Sanudo, Marino - Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis super Terrae Sanctae Recuperatione et Conservatione. Ed. J. Bongars. Hanau, 1611. Reprinted with introduction by J. Prawer, Jerusalem: Masada Press, 1972.

Tabulae Ordinis Theutonici ex Tabularii Regii Berolinensis Codice Potissimum. Ed. E. Strehlke, Berlin: Weidmann, 1869. Reprinted with Preface by H.E. Mayer. Toronto: Toronto University Press, 1975.

USĀMA IBN MUNQĪDH - The Book of Contemplation: Islam and the Crusades. Trans. with introduction and notes by P.M. Cobb. London: Penguin, 2008.

WILBRAND OF OLDENBURG - “Itinerarium”. In PRINGLE, Denys - Pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, 1187-1291. Crusade Texts in Translation 23. Trans. Denys Pringle. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012, pp. 61-94.

Wilbrand of Oldenburg - “Itinerarium”. In PRINGLE, Denys (ed.) - “Wilbrand of Oldenburg’s Journey to Syria, Lesser Armenia, Cyprus, and the Holy Land (1211-1212): A New Edition”. Crusades 11 (2012), pp. 109-137.

WILLIAM OF TYRE - “Chronicon”. Ed. R.B.C. Huygens. In Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis, 63-63a. Turnhout: Brepols, 1986.