“C’était une bâtisse construite pour la guerre plutôt que pour la religion. Greniers, celliers, caves et granges à fourrage se succédaient dans un ordre parfait. Les lieux de prière et ceux destinés aux hommes étaient des plus succincts. On respirait ici l’odeur des batailles”2.

It was not rare that the Military Orders' constructions contained fortified elements in their residential, religious or agricultural buildings. However, it is commonly perceived that the brothers didn't build real castles far from the border regions3. The two buildings presented here make us reconsider this opinion as their architectural characteristics actually correspond to the idea of a “real castle”.

These castles were located in Manosque and Puimoisson, in today’s district of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence4. Among other common attributes, they were built in the central decades of the thirteenth century, only 40 kilometers apart, they were very connected5, and very much linked to a habitat. These buildings were the expression of the lordship domination of the Military Order on the population: in Manosque as well as Puimoisson, the Hospital of St. John inherited the full jurisdiction of county lordship. Therefore, these symbols of oppression were a privileged target for revolutionary revenge: both castles were entirely destroyed, shortly after 1793 for Manosque, after 1802 for Puimoisson6. Still today, aerial photography shows in negative the mark of these buildings on the urban landscape. In Manosque, the castle was set in the south-west part of the city, on today's “Place du Terreau”, right at the edge of the medieval walls7. In Puimoisson, it occupied the top of the village, where the public square now stands.

Very sparse, the iconographic documentation has only been able to provide one starting point for the study: for both buildings, only one rudimentary blueprint, drawn before the demolition8. Our work has been therefore based mainly on written documentation of the medieval and modern eras, starting with minutes produced by visitors of the Order of Malta, particularly “improvement visits”. If the principle of regular visits had already started in the thirteenth century, the minutes were not kept in books and sufficiently detailed to be considered until the seventeenth. These inspections allow us to cross-reference different things on the blueprint. They give information about circulation and points of entry, as well as information about interior constructions (fireplaces, cupboards…), which we won't consider here because they came later. These documents cannot give precise information on the reality of architecture, but they allow us to unveil the style and the rhythm of the furbishing of the interior space. From that situation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, we can suggest careful hypotheses on the internal organization of the medieval castle. Still, only Manosque offered an important collection of thirteenth-and fourteenth-centuries charters and some account books that mention different locations and refurbishing in the castle9. Surveys in the modern era document important modifications in the organization and attribution of the spaces, but the building has remained unchanged for the most part since the Middle Ages. For example, vaulted rooms, “semicircular arches”, “lattices” of “gothic style arched doorways” or paved floors are mentioned 10.

In Puimoisson I had to start from scratch. In Manosque I was able to rely on the work of Sandrine Claude, who has already used the written sources to describe the composition and the evolution of the castle. Larger documentary research has allowed us to express new observations and go deeper in the hypothetical restitution of the building11.

Before trying to exhume these long-gone buildings, two preliminary points have to be clarified. In order to qualify these constructions and to understand how the contemporary people were seeing it, it is useful to research the terminology. In Manosque, as well as Puimoisson, since it was first mentioned until the fifteenth century, the monument was called a “palace”. This term often applies to urban houses of the Military Orders and, generally, to commanderies with important seigneurial rights12. In the fourteenth century, the fortification is often described with the expression “fortalicio vero palacii Manuasce”13. Starting in the sixteenth century it becomes a “castle” or “fortress”. In Puimoisson, there is hesitation between “palais” and “chasteau seigneurial” until the eighteenth century14. In the tradition of the knights of Malta, the main location of the seigneurial power is above all a fortified residence. If the “château” refers to the exterior aspect, the idea of a palace would qualify more accurately the status of its occupants15.

This leads to a second preliminary question: who was living in such buildings in the thirteenth century? The commandery (bajulia) of Manosque was one of the most important and prestigious houses of the Hospital in Provence. The castle itself , different from the territory of the commandery as a whole, was hosting three or four senior officials - commander, bailiff, chaplain -, a dozen brothers (knights and sergeants) and as many lay affiliates (“donats”)16. A religious community of around thirty to which we should add a few servants directly employed at the palace but whose number is impossible to evaluate. Also, the castle was frequently hosting other people, traveling brothers and honorable guests. When the Prior of Saint Gilles was on site for example, he would travel with a scribe, a chaplain, an esquire and a few servants. Puimoisson is less documented but, as its headquarters were more modest, we can easily cut the estimations of Manosque by half, so around fifteen people maximum were living in the palace17.

Beyond their common points, the two castles present a relatively important difference: Manosque had just been built by the count of Forcalquier when the Hospitallers inherited it; Puimoisson was entirely commissioned by the Order. We can then make assumptions about the composition and organization of the Manosque castle. Puimoisson, although much less documented, is geographically and formally too close to be discarded. We will then discuss the role of these buildings in the renewal of the fortified landscape which marked Provence in the thirteenth century, especially under the impulse of the Angevin lordship.

Manosque: A castle inherited and refurbished

The first mention of the building comes in August 1198, when the count of Forcalquier, Guilhem II hands various toll and common rights to the Hospitallers: the charter is then given in Manosque, in novo palatio comitis subtus capella18. After that time, the comital palace is occasionally mentioned until 120719. That year, to end the sixty-year-old conflict between the count's family and the Hospital, Guilhem II gave away all his seigneurial rights over Manosque along with his palace20. Two years later, on February 4, 1209, the prince confirmed his donation of the palace, in camera subtus cappellam, in suo scilicet sedens lecto ante furnellum21. In front of a vast assembly made of vassals, knights and burghers of the town - the Count reminded, among other things, being at the origin of the construction of the building22. Guilhem II died a few months later and the Hospitallers didn't wait long before transferring their headquarters, initially located extra muros, by the chapel of Saint-Pierre23.

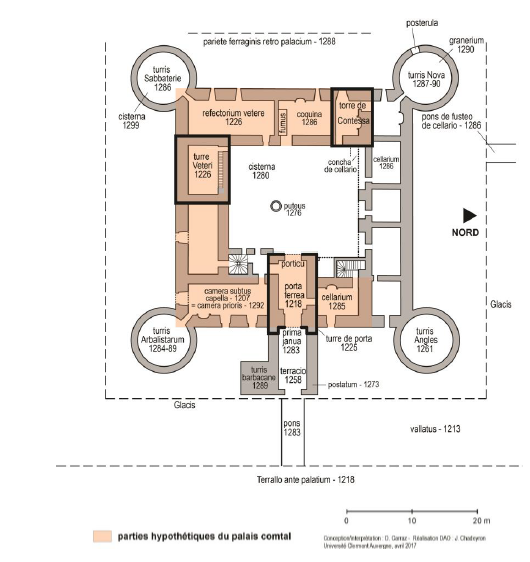

General aspect: map and defense organs

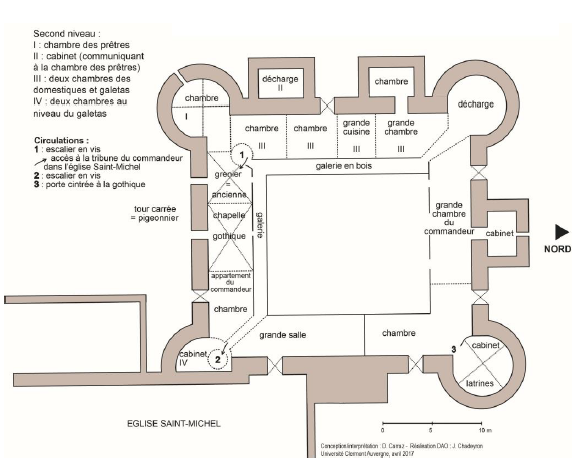

Let's leave here the origins of the installation of the Hospitallers in the comital palace to jump in time. According to the blueprint drawn in 1793 before the destruction of the castle, it seems to be a quasi-perfect square with around 40 m sides (20 “toises” by side) and an internal courtyard 22 m wide. This blueprint shows a good starting point, but it is not fully reliable because the seven towers mentioned in the visits don't appear, among which four round towers at each corner, visible on the map of the city drawn around 177324. The visits allow us to deduct the approximative position of the three so-called “square” towers, which were not necessarily exactly in the middle of the curtain walls25 (Fig. 2). The regularity of the map as it appears in 1793 should not be misleading, as it is the result of many transformations. And we can even suppose that, being a building-reconversion project, some elements have been wiped from the map if not completely demolished.

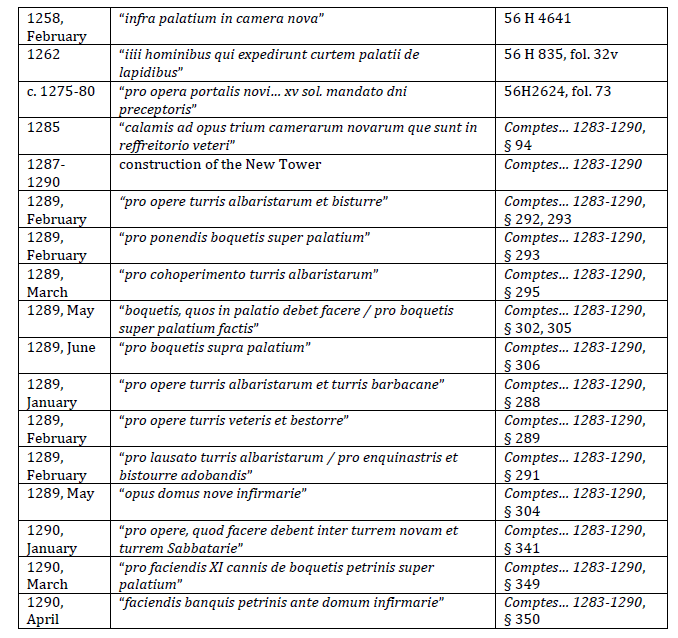

What could the palace look like when it was passed onto the Hospitallers (Fig. 1.A)? The pair camera/capella appears first, with a vast seigneurial room on the ground floor, built on top of the chapel on the first floor26. The building already had at least three towers, as suggested by the presence of a “turre veteri” and a “torre de contessa” serving as dungeon27. Moreover, the system of a porch-shaped entrance defended by a third tower and provided with two doors, with the first one preceded by a portcullis had already been confirmed28. A charter from 1226 quotes a “refectorium,” also inherited from the comital palace. From there, the Hospitallers engaged in a number of important refurbishments. In addition to the three towers dating back to the count's era, four other towers are mentioned in the second half of the thirteenth century: the “Tower of the English”29 (1261), the “Tower of the Crossbow” (1284), the “Tower of the Cordonnerie” (1286) and a “New Tower”30. The account books inform us that the “Tower of the Crossbow” is still under construction in 1289, and that, between 1287 and 1290, the various stages of the construction of the “New Tower” are mentioned, from the digging of the foundations until the hardware of the doors and windows31. So, the seven towers are mentioned in the modern era, but it is impossible to place them precisely on the map (Fig. 1 and 2) or to know what modifications some of them underwent over four centuries.

The monument has an undeniable fortified character. In the modern era, the curtain walls are still serrated, whereas the towers are crenellated and machicolated. The crenellation and machicolation of the “Old Tower” were being repaired in 128832. The so-called “great crossbow”, which probably stood at the top of the tower of the same name, was part of this ostentatious but also threatening defense33. This “Tower of the Crossbow” can easily be pictured on the main façade, facing the city. The Hospitallers didn't have much to fear from the population, but it served to confirm the rank of the lord, sole ruler of the city.

Isolation from the urban landscape serves the same goal. By its size, the castle (which stood on a platform, as a plan dating from the Revolution suggests) was crushing the entire urban space. In the modern era, it appears largely isolated by an outer-yard planted with mulberries along the curtain walls. This “promenade” was built over a ditch, which was at least partially filled34. These ditches have been attested since 1213 and might even have been equipped with a masonry glaze35. One could cross with a bridge located outside of the first door and first mentioned in 128336. It is specifically referred to as a drawbridge in 148337. From the mid-thirteenth century onwards, many charters were written on a “terrace” in front of the iron gate of the castle38. This clearing was then defended by a barbican with a tower and a fence39. Once they were installed in the castle, the Hospitallers became owners of surrounding pieces of ground and buildings, which allowed them to open a vast space to the east, known as “Terreau” since 121840. To the west was an orchard which was still accessible in the seventeenth century through a postern41. Protecting the entrance and isolating the fortification from the urban landscape was clearly a decision of the Hospitallers.

Organization of the spaces

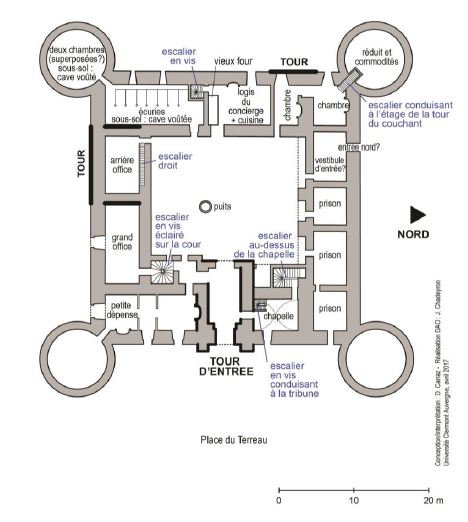

We shall begin with the general organization of the buildings as it was in the eighteenth century, if only to verify the eventuality that some spaces are still unchanged. The ground floor appears to be shared between the service quarters (stalls, basements, storage rooms…), possibly living spaces, a prison42, and a chapel (Fig. 2.A). On the first floor, the southern and eastern aisles, where the commander's apartments were, are reserved for prestigious residency (Fig. 2.B). The medieval chapel, looking down the east side, is still standing but it was turned into the treasure room. In the other aisles are the service quarters.

From the eighteenth century, let’s jump five centuries back, when charters and account books show a certain amount of information on the specifics of the spaces inside the castle. All matters relating to stewardship can be classified as follows43:

animals:

- magnum stabulum (1284)

- stabuletum (1286)

stocks:

- cisterna44 (1280)

- botellaria (1285)

- cellarium (1285) <between> [postatum] <and> [porta ferrea]

- cellarium (1286)

<preceded by> [pons de fusteo de cellario]

<preceded by> [paymento de morterio ante concham]

- salsaria (1287) <preceded by> [callata]

- turris de porta [with solerium] :

[portare bladum in -] (1287)

solerium mejanum - plenum consiginis

pro stablida (1299)

- turris Englesi

[portare bladum in -] (1287)

- turris Sabbatarie

[portare bladum in -] (1287)

cisterna Sabaterie plenam faba (1299)

- granerium turris nove (1290)

transformation:

- coquina (1286) [cum fornellum]

- sabbateria45 (1286)

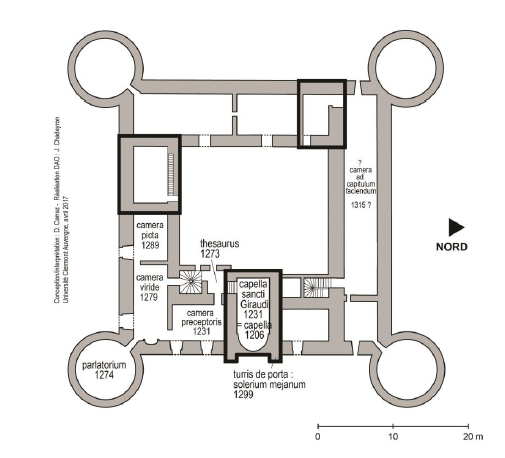

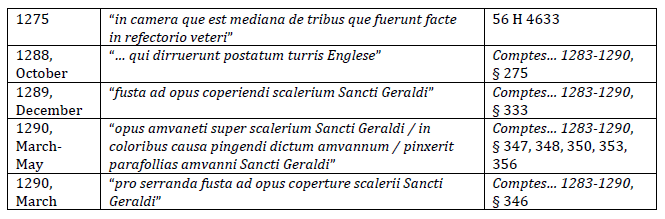

Looking at the conventual buildings, the location of the chapel is the first thing we will consider. The plan from the revolutionary period shows the chapel above the entry porch (Fig. 2.B). But, at that time, it was a treasury room because the chapel had been moved to the ground floor, on the northern side of the porch46. The position above the entrance might not be not the oldest location: in the times of Guilhem II of Forcalquier, the chapel was above a vast camera. Anyway, the Hospitallers had to repair the porch-tower quickly because the chapel was located above the entrance as early as 123147 (Fig. 1.B). The cult, dedicated to saint Géraud, was associated with a “scalerium sancti Geraldi”48. It is not a simple access point as one must connect the staircase to the wooden tribune which had its roof rebuilt in 1290 and then painted and decorated49. At last, the chapel was topped with a steeple mentioned for the first time in 135150. The treasury room, which generally served as sacristy, had to be near51.

What about the residential spaces? The maior camera, which had been the headquarters of the comital power, was still mentioned frequently in the following decade when the palace was a possession of the Hospitallers (Fig.1.A). Later, it is mentioned more sporadically, as the room was then reserved for a distinguished guest during his visits in Manosque: the prior of Saint-Gilles52. Also called “camera subtus capellam”, that room disappears because, from the 1230s, most charters were subscribed in the room of the commander53, an important location which was upstairs, near the treasury, the chapel in particular54. We find this same feature, at least from the end of the Middle Ages, in other commanderies where the apartments of the commander were connected to the chapel through a tribune55. I would place this “camera preceptoris” in the eastern aisle, suspecting it would be a rather permanent place as the apartments of the commander were there in the modern era (Fig. 1.B and 2.B). Besides, it wouldn't be too anachronic to talk about apartments as early as the thirteenth century since the commander Bérenger Monge was known to sign acts in a “parlatorium” next to his room. Here, this “parlatorium” has nothing to do with the parlor of the cloistered orders: It was apparently more a work study open to public life56. A “green room,” where Bérenger Monge was alone to issue charters, is mentioned next to the parlor57. The color probably expresses a bucolic painted decoration, which was very fashionable in courtly and seigneurial milieus at the time58. But we can't say if this “camera viride” was the same as the “camera preceptoris” or if it was a different room. Finally, in front of the green room is a camera simply called “painted”59. If we can't imagine for sure how these three or four rooms were furnished, we can guess the specifics of the public spaces, according to each activity. What emerges of this complex program, is a special attention given to the majesty of the decorum where the rooms got their names to them from the way they were decorated. This reminds what Paul Deschamps wrote about the “room of the master” in castles of the Latin East. At Crac des Chevaliers, the “apartment of the lord of the castle” which was located in one of the towers of the southern side, was decorated in the years 1230-1240” 60.

Since the mid-thirteenth century at least, the tendency among commanderies had moved toward a privatization of spaces and the loosening of communal life61. Rooms were therefore affected to other officials of the convent (priest, bailiff, treasurer…)62. These weren't necessarily located in the aisles because, while the ground floor of the towers was used as storage, the upper floors were inhabited, as evidenced by the chimneys63. Also, the fact pavement had been laid in the “New Tower” and the “Tower of the Crossbow” would suggest that the various levels of the towers were vaulted rather than framed64. Several other rooms appear in the documents, some “old,” some “new”. To all it is impossible to attribute a function65. The dormitory, on the other hand is not mentioned anywhere, which only confirms observations made for most of the commanderies where the common room is no longer attested after the twelfth century66. The refectory is a more enduring symbol of monastic life: although the former dining room was dismantled, a refectorium reappears in 129967. Finally, after the Hospitallers settled in the castle, account books attest that a chapter room and an infirmary had to be built, where the brothers went to relax68. Now, how to give a little more dynamic perspective to this inventory of spaces?

Under permanent construction

The regular maintenance and adaptation of the living conditions were such that such a monument was constantly evolving. If it is difficult to know about the interventions of the Hospitallers in the four or five decades that followed their arrival in the castle. The documentation sheds light on the activity employed in the second half of the thirteenth century. Beside the frequent maintenance works attested by the account books, we can spotlight the following mentions:

Significant work was done in the last third of the thirteenth century: new spaces were added (at least one new room and one infirmary) and at least than four towers came out of the ground. These new constructions, I believe, are the four circular towers69 (Fig. 1.A). New arrangements seem to have also taken place at the upper level of the existing buildings where the pose of stone brackets is attested. The internal compartments are modified as well. Three rooms are refurbished in the former refectory, which shows a tendency of specialization of the spaces. On the upper floor, the area around the St. Geraud's staircase and the tribune was also covered and embellished, maybe during the restructuring of the commander’s “suite”70.

All these constructions can be linked to the ambitions of Bérenger Monge, commander of Aix and Manosque during the entire second half of the thirteenth century. In Manosque, he had built a reputation as the leader of the religious community he was in charge of and sole ruler of the city and its inhabitants. In Aix, he also imposed himself as a master builder, and conducted for Charles I of Anjou the reconstruction of the priory church in a gothic style never seen before in Provence71. There is a great deal of evidence that shows Bérenger Monge at the head of the important program which deeply restructured the old comital palace and gave it its general appearance, which remained mainly unchanged until the Revolution. Some works are also attested in the first part of the fourteenth century, like the reconstruction of a tower and the campanile of a chapel.

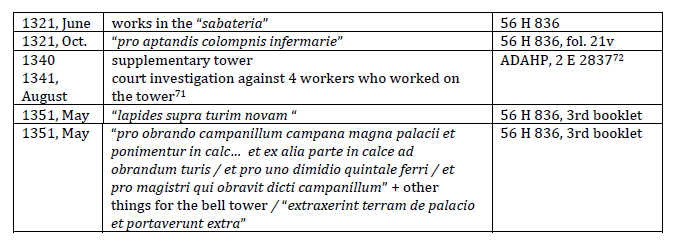

The dispersion of the late medieval documentation, which has not been entirely unveiled, can explain these sporadic mentions72. Another reason is the new context facing the Hospitallers73. Financial difficulties, a lack of leadership despite the need for reform, wars, and, finally the strengthening of the monarchy and the rise of a municipal conscience: all these obstacles didn't encourage serious reconstructions in the castle. Even maintenance seems to have been neglected; at the end of the fifteenth century, the fortification appeared derelict 74. The Bailiff Jean de Boniface (1536-1545) engaged serious restorations but with no real effect on the general structure of the building75. One thing is certain: between the sixteenth century and the Revolution, it was progressively adapted to the taste of the day plop with elements mentioned in the visits: main spiral stairway, cross windows, chimneys… Yet it doesn't seem that the medieval matrix was profoundly changed.

Hospitallers’ castles and castle architecture in the thirteenth century

A Castle Built Ex Nihilo: Puimoisson

To settle in the locality of Saint Michel, the Hospitallers benefited from the support of the Bishop of Riez who gave them the parish church (ca. 1125), and of the count of Provence who gave them the rights on the villa (in 1150)76. The Hospitallers waited until the end of the century to launch a land-ownership campaign. In 1231, the Prior of Saint-Gilles, Bertrand de Comps, received sole lordship on the castrum of Puimoisson from the Count Raymond Bérenger V. Probably soon thereafter, the brothers moved their headquarters from the villa to the castrum and built a new house on the highest peak of the plateau, flanked by a parish church which kept the name of Saint-Michel77. Like in other Provençal sites, the settling of the headquarters and the moving of the parish church led to a new polarization in the settlement, causing the primitive site of the village (villa) of Saint-Michel to be dropped progressively.

For this reason, the name of the brothers’ residency is pretty instructive. We found, in the years 1230-1240, the expected title of “ospitale Podii Moisonis” or “domus ospitalis”, but we find, around 1250, the localization “in castro Hospitalis de Podio Moisono”78. We can't determine if that applies to the fortified village (castrum) or to the Hospitaller house which was then remarkably fortified. The ambiguity is interesting in itself. The first occurrence of the term “palatium” appears in 126479. We suppose that the apparition of this name corresponds to a new architectural program showing with spark the strength, now firmly established, of the ecclesiastical lordship. Yet, the medieval documentation doesn't give a single clue on the aspect of the building, other than “bonum fortalicium” in 137380. The spaces quoted in the charters of the thirteenth century correspond to what we know of the usual composition of the commanderies: the one in Puimoisson therefore included a large room apparently near the main entrance, a porch, a refectory, a room of the commander, a cellar, a kitchen81. Note that, unlike Manosque, the palace was hosting the court of justice, at least in the fourteenth century82. Despite scanty information on the medieval state, the evocation of the palace in modern times is especially worthwhile for a comparison with Manosque.

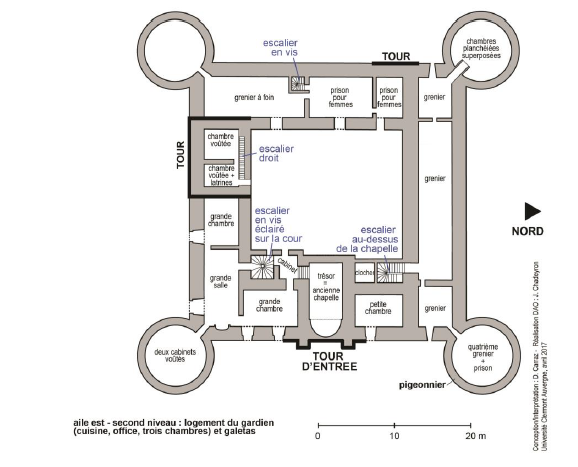

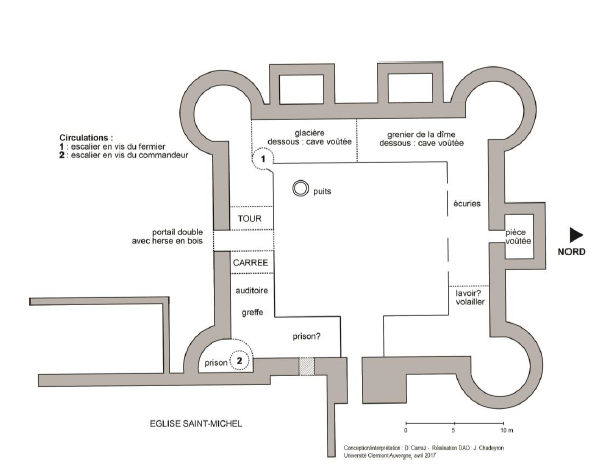

Other than the visits of the order of Malta, we have a description at the beginning of the nineteenth century which gives a few dimensions83. Occupying a surface area of 524 m², the building developed on a rectangular plan of 27 m. by 25 m., with a courtyard of 16 m. by 14 m.. This building was then smaller than Manosque. It was flanked at three angles with 16 m. high crenelated circular towers and four other 12 m. high square towers, two of which were on the west side and the other two on the north and east sides (Fig. 3). Built in cut stone, the exterior perimeter was 1.50 m. wide, 12 m. high. In the nineteenth century, the main entrance seemed to have been on the east side84. But before that, it was on the south, through a so-called squared tower in which there were two doors separated by a wooden portcullis, a similarity with the house of Manosque85.

According to the visits of the Order of Malta, the ground floor was the service area (cellar, ice house, stables) and the auditorium the area of justice, with a prison86 (Fig. 3.A). On the first floor, the apartments of the commander expanded to the north wings, to the east and even to part of the southern wing; on the west aisle, a row of rooms with a kitchen were used by the farmer. A former gothic chapel, which occupied the rest of the south aisle, had been turned into a barn87. It was located above the gate within a square tower extended by a dovecote88. After the chapel was abandoned, the Hospitallers used the parish church next to the castle. According to a common usage in the commanderies, a tribune was reserved for the commander with a direct access from the castle to the church89. The circular towers, which were cross-vaulted, were occupied by rooms or extensions (Fig 3.B). On the second floor, the garret, were the rooms of the servants, a classical disposition in modern castles. Finally, unlike in Manosque, we notice the presence of a wooden gallery in the western and southern aisles90. It seems to have originally been made for the commander to go directly from the southern aisle to the western aisle, probably to reach the stairway leading to the tribune in the church.

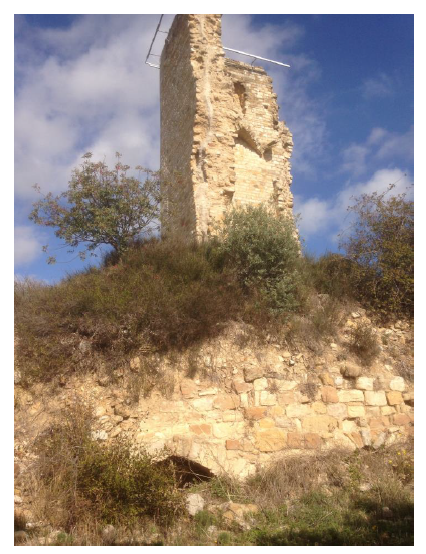

As in Manosque, everything suggests that the castle of Puimoisson, as it appeared between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries, largely matches the medieval monument, only impacted by some of the usual “modernization” that followed the Wars of Religion91: large crossed windows were built, a second level underneath the attic with a gable roof was added (Ill. 1). I would be inclined to locate the main phase of construction of the palatium of Puimoisson in the central decades of the thirteenth century. Like in Manosque, the Hospitaller lordship is then at the height of its power and its chief is a very important person: Féraud de Barras, who cumulated the charges of Prior of Saint-Gilles (1245-1269) and commander of Puimoisson (1246-1264)92. This nobleman, who came from a family based in the diocese of Digne, enjoyed coming to Puimoisson. There, he exercised full jurisdiction on behalf of the Hospital and received homage from the local lords. He could have decided to build a house that projected a certain social status. It wasn't quite the only monumental marker of the Hospitaller lordship because, in the same central decades of the thirteenth century, the brothers of Puimoisson rebuilt the church of Saint-Apollinaire, a “magnificent stone cube built like a fortress“93 (Ill. 2). The intense building activity that we can imagine at this period in the Hospitaller lordships of Manosque and Puimoisson was related to a certain renewal of the fortified architecture which was a trademark in Provence at the time.

A renewal of fortified architecture

The Capetian rule over Languedoc and Provence through the Angevine branch, induced the rebuilding - or more rarely the creation ex nihilo - of numerous fortified sites94. However, we attribute to this context the introduction in meridional ground of the quadrangular designed castle with a courtyard. Let's just mention a few examples95. The fortress of Beaucaire (Gard), having probably been rebuilt since the reign of Louis VIII and finished under his successor's rule, shows a vast trapezoidal perimeter wall with circular towers96. Not far from there in Fourques, the old castle of the counts of Toulouse was entirely rebuilt by the Capetians at an unclear date, sometime between the reign of Saint Louis and Philippe le Bel: we find a rectangular design flanked by angular quadrangular towers, with buildings on the curtain walls. In even more modest proportions, the square of Châteaurenard (Bouches-du-Rhône) was rebuilt by the count of Provence in the last third of the thirteenth century: the central trapezoidal body (23 m x 11 m) shows four circular towers97. Closer to Manosque and Puimoisson, the castle of Gréoux features a more complex ensemble, like Manosque, with a farm yard and a first perimeter wall98. The dimensions are comparable (49 m x 38 m) and the quadrangular design shows an exemplary regularity. The reconstruction of the former castle shows large volumes of living space in the aisles, a row of rooms on two levels and, on the other side a vast square tower leads the defense on the north west angle. The ambitious program, probably commissioned by Arnaud de Trian in the second quarter of the fourteenth century, appears later than Manosque, which could have been used as a model99.

Finally, in Manosque itself, besides the large destruction, some remains attest the fortification program engaged by the Hospitallers. On the Mont d'Or hill, where the former castle was, we find the remains of a little fortified ensemble (Ill. 3). It is composed of a high master tower surrounded by a square perimeter wall, protected by prominent circular towers100. This stronghold, ruled by a preceptor castri, could have been reconstructed in the second third of the thirteenth century, maybe when the Hospitallers were rebuilding their castle in the lower city.

Apart from the model, the aspect of the two Hospitaller castles is very close to some important commanderies of cities or big villages. The Templar house of Monfrin, for example, showed many attributes of the urban palace, as well as elements of military architecture - massive walls with little openings and square crenelated towers at the angles101. Even more than the “military” status of its occupants, this type of program should be seen as a manifestation of seigneurial domination. The episcopal palaces are built in the same spirit, like the one of the archbishops of Arles in Salon which really had the status of an urban castle102. Probably rebuilt in the second half of the thirteenth century, it was noticeable, with its two towers. A closed forecourt fronted the castle, with a gateway protected by a ditch and draw bridge. The gateway was a real place of expression of the seigneurial power and we can picture a similarly monumentalized entrance front in Manosque. Indeed, dozens of charters have been written “before the iron door of the palace” of the Hospitallers. All these dispositions show the means actually used by the Military Order: the defensive system with portcullis was not exactly an innovation, but it had not been seen in Provence before Charles I of Anjou. In the middle of the thirteenth century, the use of a draw bridge was still limited to princely fortresses (Beaucaire, Hyères)103.

The Hospitaller castles of Manosque and Puimoisson (the latter could be seen as a reduced model of the former), were integrated in the innovative trends of military architecture of Provence in the thirteenth century. An originality particularly strikes the attention: the position of the chapel above the entrance. To our knowledge, it hasn’t been seen in any castle or palace in Provence, so we could wonder if it were a particularity of the Hospital, maybe brought from the Holy Land, where prestigious examples exist, the most accomplished one in its form being probably the castle of Belvoir. The Templars also positioned the chapel above the entrance at Latrun (around 1180?) and at Sidon Sea Castle (after 1260), where the sacristy next to the chapel defended the entrance of the place104. In the templar castle of Miravet, in Aragon, the high chapel, placed on the northern aisle of the quadrangle, flanked the dungeon defending the entrance to the second perimeter wall105.

With their impressive volumes both monuments of Manosque and Puimoisson dominated the urban core of their respective agglomerations and the visibility of their fortified character clear showed the nobility and the military power of the Hospitallers. As eminent lords, they were able to prepare for war if requisitioned by the count of Provence (cavalcade), the castle of Manosque being highly armed106. However, the castles played a real military role during the wars of religion rather than under the Hospitaller rule. Anyway, scholars are aware that the symbolism of castle architecture cannot be ignored. As Alain Salamagne says, ditches, walls, draw bridges, crenellations and machicolation were the “plastic symbols” that represented seigneurial power107. While the complexity of the architectural program is intended to represent the power and wealth of the builder, the quadrangular plan, adopted primarily to manifest princely domination, refers to the idea of hierarchical order. In this respect, in Manosque as in Puimoisson, the Hospitallers were part of the continuity of a power of kingly nature inherited from the Counts of Forcalquier and Provence.

Bibliographical References

Manuscript Sources

Città del Vaticano, Archivio Apostolico Vaticano, Collectoriae, 419 A.

Digne-les-Bains, Archives Départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, L 383.

Manosque, Archives municipales de Manosque, KKb 23.

Marseille, Archives départementales des Bouches-du-Rhône, B 303; 56 H 68; 56 H 126; 56 H 252; 56 H 263; 56 H 835; 56 H 841; 56 H 849bis; 56 H 4627; 56 H 4628; 56 H 4629; 56 H 4632; 56 H 4633; 56 H 4636; 56 H 4638; 56 H 4639; 56 H 4640; 56 H 4641; 56 H 4652; 56 H 4666; 56 H 4668; 56 H 4676; 56 H 4677; 56 H 4682; 56 H 4826; 56 H 4827; 56 H 4836; 56 H 4852; 56 H 4855; 56 H 4861; 56 H 4862.

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms lat. 16.

Printed sources

Cartulaire du prieuré de Saint-Gilles de l'Hôpital de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem (1129-1210). Ed. D. Le Blévec, A. Venturini. Turnhout-Paris: Brepols, 1997.

Cartulaire général de l'ordre des Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean-de-Jérusalem (1100-1310). 4 vols. Ed. J. Delaville le Roulx. Paris : E. Le Roux, 1894-1906.

COLOMBI, Jean - Histoire de Manosque [1662]. Trad. H. Pellicot [1799]. Apt: Imprimerie de Joseph Tremollière, 1808.

Comptes de la commanderie de l’Hôpital de Manosque pour les années 1283 à 1290. Ed. K. Borchardt, D. Carraz, A. Venturini. Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 2015.

Livre des privilèges de Manosque. Cartulaire municipal latin-provençal (1169-1315). Ed. M.-Z. Isnard. Paris-Digne: Impr. de Chaspoul, Constans et Vve Barbaroux, 1894.

RAYBAUD, Jean - Histoire des grands prieurs et du grand prieuré de Saint-Gilles. t. I. Ed. C. Nicolas. Nîmes: Imprimerie Clavel et Chastanier - A. Chastanier, 1904.

Recueil des actes des comtes de Provence de la Maison de Barcelone - Alphonse II et Raymond-Berenger V (1196-1245). Ed. F. Benoit. Paris: A. Picard, 1925.

SHATZMILLER, Joseph - Médecine et justice en Provence médiévale. Documents de Manosque, 1262-1348. Aix-en-Provence: Publications de l’Université de Provence, 1989.

Visites générales des commanderies de l'ordre des Hospitaliers dépendantes du Grand Prieuré de Saint-Gilles (1338). Ed. B. Beaucage. Aix-en-Provence: Université de Provence; Marseille: Laffitte, 1982.