Introduction1

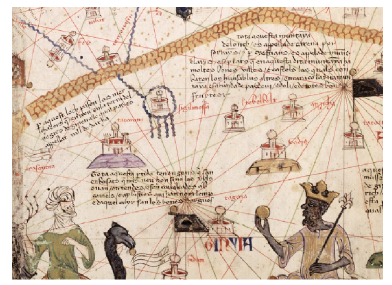

At its height in the 14th century, the fame of the empire of Mâli spread throughout the Islamicate2 and Christian worlds. Representing the furthest reaches of the world known to a Jewish Catalan cartographer, the Catalan Atlas, a large portolan map dated to 1375 and preserved today in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, bears witness to this prestige. On the lower left part of the map, i.e., in Sub-Saharan Africa (the Saharan desert is called “ASHARA” on the map), a black-skinned king wearing a crown sits in majesty, holding a scepter in one hand, and a golden orb (possibly a large gold nugget) in the other (fig. 1)3. Names are written around him, including “GINYIA”, presumably, according to the cartographer, the name of his kingdom - a hotly debated moniker which makes its first appearance on this map (before morphing into “Guinea,” the term widely used in early modern Latin Europe to designate various regions of Africa). For Arabic chroniclers, geographers and travelers, this West African polity was called Māli (with various spellings); it has been referred to as the Kingdom (or Empire) of Mali in the scholarly literature, a name that has recently started to be spelled Māli or Mâli in order to avoid confusion with the current-day Republic of Mali. On the same map, other names accompany small icons representing cities. To name but the four in front of the king: “Tagaza” (Arabic Taghâza, a salt mine in the extreme north of present-day Mali), “Sudam” (obviously the Arabic word Sûdân, plural for “Black”, an unknow place, if indeed one at all), “Tenbuch” (today’s Timbuktu on top of the Niger Bend in Mali), and “Ciutat de Melly”, “City of Mâli” or “Mâli City” in Catalan. This article deals with the latter, a likely evocation of the imperial capital of Mâli in the 14th century, whose location - and sometimes very existence - has been much discussed in the scholarly literature. Indeed, that the capital of a famous medieval polity appearing on a contemporary map could have since “disappeared” from the archeological record and from the memory of the local people is a paradox that remains to be solved. In this article, the expression “imperial capital” is used to distinguish it from other possible sites associated with the rulers of Mâli; the substantive “Empire” and adjective “imperial” are discussed below.

Mâli: An overview

The author of the Catalan Atlas knew quite a few things about Mâli. A caption in Catalan above the king’s left shoulder reads appreciatively: “This Black lord (senyor) is called Musse Melly, lord of the Blacks of Gineua. This king (rey) is the richest and the most noble of the whole region, because of the abundance of gold that is collected in his land”4. The Catalan Atlas is interesting not only for the information it contains, but also for the light it sheds on how knowledge of Mâli circulated at the time the atlas was drawn in the early 1370s. A diplomatic gift from Pierre IV, king of Aragon, to Charles V, king of France, the atlas was probably commissioned from Elisha ben Abraham Cresques, a Jewish cartographer from Palma de Majorca in the Balearic Islands, a commercial crossroads between Christian Europe and Muslim North Africa5. The Jewish presence in Majorca had sharply increased around the middle of the 13th century, when, after suffering decades of massacres and forced conversions under the Almohad dynasty in North Africa and al-Andalus, North African Jews resettled in the Balearic Islands and Catalonia at the invitation of Aragonese King James I. While it is unclear whether Jewish communities active in trade had resettled in North Africa at the time of the Majorcan cartographers, what is clear is that the cartographer of the Catalan Atlas had knowledge, however indirect, of the north African and trans-Saharan route to Mâli. This familiarity is reflected on his map by the placement of the cities of Sijilmâsa (in today’s Morocco), Taghâza, and City of Mâli, which follows precisely the route taken by the Tangerine traveler Ibn Battûta - who, incidentally, was also the first author to mention Timbuktu - in 13526; this in itself is evidence that the cartographer had up-to-date information on the whereabouts of Mâli. On the other hand, if he still believed that Mûsâ was king in 1375 (the monarch had in fact died at an unknown date around 1335), it is either because he borrowed the information from a previous map, or because the information had taken a different, longer path to reach him. Indeed, the most affluent members of the Balearic Jewish community were involved in long distance trade along the Mediterranean Sea and could well have heard about Mûsâ of Mâli from fellow Jewish or Muslim correspondents in Cairo, where the king’s generous gifts of gold in 1324 while en route to the hajj in Arabia were still talked about decades later7.

The so-called imperial age of the Kingdom of Mâli lasted from the mid-13th century, when Mâli conquered other regional polities like Ghâna, to the beginning of the 15th, when it lost its political hegemony to rival polities like Songhay. The splendor of imperial Mâli was never entirely forgotten by West African societies; on the contrary, as Hadrien Collet has recently shown, it remained a major stratum in the memory of, and a political model for, urban Muslim scholars from different regions of West Africa until the 19th century8. In the West, the history of Mâli (or rather, that there had once existed a polity called Mâli and that it had a history) was re-discovered in the 19th century, mostly thanks to the British armchair geographer William Desborough Cooley9. Since then, modern academics have produced a number of monographic works devoted to the history of Mâli: German traveler Heinrich Barth10; French military officer Louis-Gustave Binger11; French colonial administrators Maurice Delafosse and Charles Monteil12; Israeli historian Nehemia Levtzion13; Guinean historian Djibril Tamsir Niane14; Malian historian Madina Ly-Tall15; and African-American historian Michael Gomez16, to cite only a few of the most significant ones. The present author recently made his own contribution17.

The documentation, and this word is used here lato sensu, available to historians of Mâli is varied to the point where it can appear intimidating or discouraging. True, this diversity can sound challenging to anyone not prepared to venture outside of the supposed safety of the written documentation. And challenging it is, not the least because each category of documents offers only a partial view of the history of Mâli - from a certain place, date or thematic or ideological angle. The Tifinagh and Arabic epigraphic documents from present-day Mali, masterfully edited and studied by Brazilian philologist and historian Paolo Fernando de Moraes Farias, offers unique evidence for an early period (11th to 14th century), but their historical relevance is mostly limited to the regions of Tadmekka and Gao where they were found, regions which were only marginally and temporarily affected by the history of Mâli18. Other written documents such as discursive accounts of Mâli, including those by contemporary luminaries like al-Umarî, Ibn Battûta, and Ibn Khaldûn, all of which have been comprehensively edited, provide a wide range of social, geographical and political descriptions of Mâli19. Such accounts are rarely based on first-hand knowledge (except for Ibn Battûta, which does not make his account any less open to critique20), but rather on the testimonies of foreign merchants or clerics who had lived in Mâli, as well as of clerics or dignitaries from Mâli itself who travelled to the Islamicate world. In addition to the Catalan Atlas and other Jewish and Christian Catalan and Italian maps, European written documents, which include Portuguese and Italian accounts from the mid-15th century on, offer a late, distant viewpoint at a time when the kingdom of Mâli had shrunk to the southwestern regions of Mali and the adjacent regions of eastern Guinée-Conakry. Epigraphs were not the only written documents produced in West Africa, local historians also penned chronicles, such as the Târîkh al-Sûdân written in Timbuktu in the mid-17th century21. Again, although they display a genuine interest in the imperial age of Mâli, such chronicles speak to us from a rather lateral viewpoint, as their authors were mostly interested in documenting the vicissitudes of their own times. The genre flourished in many regions of Africa from the 15th century on22. Moreover, authors played on its success to influence readers; Mauro Nobili, for instance, has recently demonstrated that the famous text called the Târîkh al-fattâsh is actually a 19th century prophecy disguised as a 17th century chronicle23.

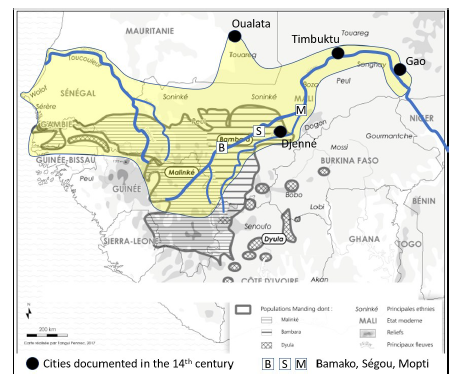

Oral traditions are another category of documentation available to the historian of West Africa24. Until quite recently, versions of a tale called the Epic of Sunjata were performed by local jeli (the Mandinka word for “bards”, also called “griots” in West African French) in Mali, Guinea-Conakry and Gambia. This long, improvised poem narrates the birth, youth, exile, and return of a hero named Sunjata, his formidable battles against an evil king-cum-sorcerer, and finally the unification of Mande (the Mandinka name for Mâli) under his leadership. One of the variants achieved international fame under Guinean historian Djibril Tamsir Niane25; others were duly recorded and made available in transcriptions in the original language as well as in translations26. The existence of a historical Sunjata around the mid-13th century is not in doubt, as the Arab historian Ibn Khaldûn mentions that the founder of the royal dynasty of Mâli was named Mârî Djâta (in both cases, the main component of the individual’s name is jata, the Mandinka word for “lion”); but the historicity of most of the characters, events, and places mentioned in the epic is open to debate27. In any case, the Epic of Sunjata is certainly not a window onto historical “truth”: rather, it is a repository and patchwork of representations from different periods the Mandinka had about their origins, social organization and values. It also approaches the history of Mâli from a distinctly rural, southern viewpoint, not the least because most versions were collected among Mandinka speakers, who live in what was once the southwestern region of the former empire (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Geographical extension of the kingdom of Mâli in the 14th century and current linguistic map of West Africa (after PERSON, Yves - Historien de l’Afrique, explorateur de l’oralité. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2018, p. 61).

Material evidence constitutes another category of documentation. A number of archaeological excavations, field surveys, inventories, and artefact studies have been carried out in the regions once covered by imperial Mâli. The patchy knowledge accumulated up until 1961 was synthetized in Raymond Mauny’s still-useful Tableau géographique de l’Ouest africain28. Large-scale excavations later took place at Niani (a potential candidate for the capital of Mâli, to which we shall return soon), as well as at the urban sites of Koumbi Saleh (the likely former capital of the kingdom of Ghâna, one of Mâli’s predecessors), Djenné and Gao29. Despite these major excavations, archaeological documentation is still extremely limited, which means that most potential vestiges belonging to the medieval period remain to be discovered. Exacerbating factors likely contributed to this scantiness. In addition to the natural erosion of the vernacular earthen architecture - called banco in West African French - of the Niger River valley - an architecture that “melts down” very quickly whenever the constructions are not regularly maintained and periodically rebuilt, as has been the case in Timbuktu up to the present30 -, unscrupulous individuals have plundered the ground searching for terracotta sculptures (called “Djenné”) and other artefacts to sell the on the black market - a curse that implies that sites still unknown to archaeologists have already been largely destroyed31.

The king as two: Dual political structures and legitimacies

Instead of lamenting the fact that much available evidence is diverse and fragmentary, perhaps historians of Mâli should view the situation as an opportunity to allow the alternate viewpoints preserved in the documentation to shed light on aspects of the past that are better understood complementarily. For example, in lieu of endlessly trying to reconcile Arabic written accounts with oral traditions, perhaps it would be more fruitful to view them as highlighting facets of the past completely absent from the other. Thus, Arabic accounts penned by foreigners or local inhabitants, which were focused on trade, offer abundant and precious information on the kingdom’s urban, Muslim, northern fringe, while mostly ignoring the social realities of the countryside behind (i.e., to the south of) the Sahelian belt. Moreover, it is remarkable that the foreigners were so ignorant - if not deliberately kept in the dark by their Mâlian partners - about where gold was supposed to come from32. Likewise, perhaps we should not be surprised that the jeli have very little to say about the great sultans of 14th century, Islam, the cities of the Sahelian belt, trade, and other contacts with the outside world; it was as if the southern focus of Mandinka society had pulled down a veil, hampering the reception of this information.

That the founding and history of Mâli were remembered - however selectively - in the Mande is evidence enough that the former southwestern province of the empire had a close relationship with the ruling dynasty, likely because it had been its birthplace in the mid-13th century and became its homeland again when the empire started to retract in the 15th century. I have suggested elsewhere that we conceive of the Mande (or perhaps a part of the Mande) as the royal domain of the dynasty (or at least of a branch of the dynasty), that is, the region over which they had ruled since the time of Sunjata33. Outside these lands, the king of Mâli was not the traditional ruler; rather, other rulers recognized him as their overlord. For indeed, all the societies and communities that were incorporated into the empire of Mâli had their own traditional rulers, whether their rulership was based on territory, ethnicity (as seems to have been the case in Ghâna, whose ruler preserved the title of “king” even under the suzerainty of the king of Mâli, and along the Niger bend, where the Songhay retained their koï), or kinship (which clearly was the case among Berber communities in cities like Oualata and Timbuktu). As the Arabic sources make evident, these traditional rulers found their authority closely checked by Mandinka farba or governors; Ibn Battûta even watched uncomfortably, because of the racial implications, as the sheikh and other dignitaries of the Berbers of Oualata had to formally submit to a Black officer, the official representative of Mâli34. Such a system can hardly be called a “federation of chiefdoms”35; rather, because sovereignty was exercised at multiple scales, it is better described as an empire. In any case, the duality of politics in Mâli is well captured by the king’s titles: he was both a mansa (Mandinka “chief”, “king”), the traditional ruler of the Mandinka by virtue of his ascendance, and a sultan, an Arabic term used by Islamicate rulers who claimed the temporal arch-authority of any territory36. These two dimensions of the Mâlian kingship must not be confused, not only because they had different territorial applications, but above all because they implied different sources of legitimacy, namely kinship and homage (whether by choice or by force). In other words, the king’s subjects (the Mandinka) who recognized him as their mansa were not the same as those who recognized him as their sultan, although it is not impossible to think of overlaps. Oral traditions have preserved the memory of the former, Arab informants mostly met the latter.

Nowhere was this dual political structure more visible - and deliberately so - than during certain ritual and festive occasions at the court of the imperial capital of Mâli37. On the two most important holidays of the Muslim calendar, the Eid al-Fitr (the “Feast of the Breaking of the fast”) and the Eid al-Adha (the “Feast of the Sacrifice”), celebrations started late in the morning at the musallâ, an open-air mosque - whose ritual space was generally demarcated by a stone lining on the ground or by a small surrounding wall - not far from the royal palace. There, in the presence of the king and both local and foreign Muslims, the predicator gave a prayer and then a khutbâ (“sermon”) in Arabic. These were followed by the secular portion of the ceremony, when, descending from his chair, the predicator delivered a eulogy to the sultan and an exhortation to the faithful to obey him and pay him his due; it was given in Arabic and then translated, presumably into Mandinka. Apart from the translated exhortation, which was perhaps for the benefit of non-Muslims observing the ceremony from outside the musallâ - although it could have been for the benefit of non-Arabic speaking local Muslims as well - this was par for the course in Islam. But what came next is more puzzling. Later in the day, everyone moved to the mechouar, the parade square adjacent to the palace. There, the king sat on a platform erected under a tree. The Muslims, royal officers and slaves formed parallel rows in front of him, flanking a space left empty for the show that was about to start. Then came a singer who celebrated the sultan’s exploits, accompanied by dancers and jugglers. And then came the turn of people whom Ibn Battûta calls “poets”, but we are fortunate that he gives us the local name spelled out in Arabic, djâlî, in which we recognize the Mandinka word jeli, meaning griots or bards. “Each of them”, he says, “has enclosed himself within an effigy made of feathers […], on which is fixed a head made of wood with a red beak”38. These are masks in the West African sense of the word, where they are understood as both objects (in this case, not just face masks but a costume covering the body) and the embodiments of deities39. Who these deities were is a matter of conjecture; but given that the masked dancers celebrated the king’s forefathers and that masks performed similar functions in West Africa in more recent times, it is likely that they represented the ancestors (that is, deities that belonged to and protected a given lineage)40. Regardless, what is certain is that the king who attended the morning prayer at the mosque and the afternoon dances of the masks was not the same ruler though he was one and the same person: he “recharged” his legitimacy in different ways for different subjects.

The capital of Mâli: Thinking with its duality to rethink its location

The ceremonies described in the previous section took place at a site that cannot but be the imperial capital of Mâli. It is significant that the capital was possibly the only place in the empire where the dual aspects of the political structure of Mâli intersected. It is also remarkable that, given all our knowledge about the Muslim and traditional-religious ceremonies that took place there - between the palace, the musallâ and the mechouar -, we still don’t know where it was located. The search for its location has been something of a quest for as long as a scholarly interest in the history of Mâli has existed41. One of the main reasons why this question continues to frustrate scholars is that Arabic sources give scant details about how to get to the capital from North Africa and even less about its physical environment. Writing in the 1330s based on information gleaned from an informant who had lived in the capital for 35 years, the Mamluk chronicler al-Umarî says only:

“The city of BYTY is extensive in length and breadth. Its length would be about a barîd [20 km] and its width the same. It is not encircled by a wall and is mostly scattered. The king has several palaces enclosed by circular walls. A branch of the Nîl [=the river] encircles the city on all four sides. In places this may be crossed by wading when the water is low but in others it may be traversed only by boat”42.

Ibn Battûta, who visited in 1352, provides his readers with only an itinerary from Sijilmâsa to Walata, and from there to a village called Kârsakhû along the “Nîl”, which is difficult to trace on a map because Kârsakhû and other places he mentions either no longer exist or remain unlocated. He goes on to say rather dryly: “Then we departed from Kârsakhû and arrived at the river Sansara, which is about ten miles from the capital of Mâlî. […] I crossed it by the ferry […]. I arrived at the city of Mâllî, the seat of the king of the Sûdân […]. I arrived at the White quarter”43. Another reason why the capital has been so difficult to locate is its name. Some Arabic sources do indeed provide a name, not just the descriptive expression “City of Mâli”. But this name has come down to us, in the manuscripts, in forms made almost useless by the irregular marking of the vowels and of the diacritics under the consonants, which make the possible renderings as varied as Biti, Bati, Nani or Yati (among tens of others)44, and the identification of such toponyms on the map, a hopeless (or hopeful) guess. Still another reason for the uncertainty of the location of the capital of Mâli may also be related (as will be suggested below) to the ambivalence of its economic function.

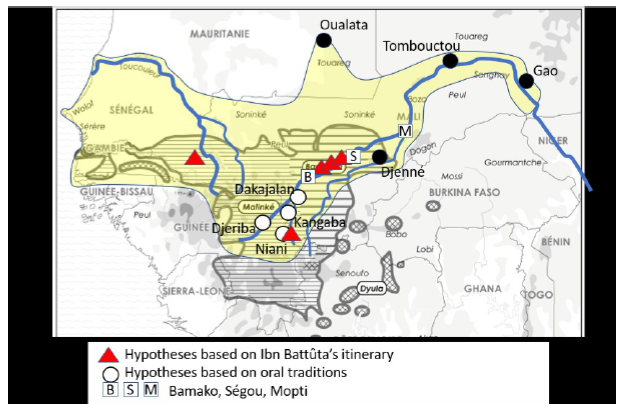

Scholars have come up with a number of hypotheses for the location of the capital of Mâli. As these have been surveyed elsewhere, we shall not do so here45. Instead, one need only glance at the map (fig. 3) to see that hypotheses based on Arabic written accounts (mainly Ibn Battûta’s) tend to favor a putative location on the left bank of the Niger River between current-day Bamako and Ségou; such is the case for John Hunwick’s hypothesis, the most recent aside from the one presented in this article46. Claude Meillassoux’ hypothesis of a location in the upper Gambia River valley is an outlier in this respect47, which, if nothing else, illustrates that there is room for interpretation when it comes to Ibn Battûta’s itinerary. The oral traditions, on the other hand, favor locations upstream from Bamako on the Niger River, much more southerly than those based on written documents. Again, this bimodal spatial distribution is a testament to the sharply divergent viewpoints presented by written and oral documentation, which leave little room for overlap. The sole exception is Niani, a small village in what is today eastern Guinea, which is considered Sunjata’s capital in some local versions of his Epic. As if to make the argument more compelling, Niani features among the possible readings of the names provided in the Arabic sources, and the village happens to be situated on the bank of a tributary of the Niger, namely the Sankarani, whose moniker could also be an echo of the Sansara mentioned by Ibn Battûta. The Niani hypothesis gained traction as early as the 1920s; archaeological excavations carried out there by Władisław Filipowiak and Djibril Tamsir Niane half a century later48 convinced many scholars Niani was indeed Sunjata’s capital as well as the city visited by Ibn Battûta and described in other Arabic sources. Yet it is now accepted that this hypothesis was built on, and gained the appearance of veracity from, a combination of self-serving assertions by historians-cum-colonial administrators, circular reasoning by researchers, strong political pressure on the excavators, and misunderstanding of radiocarbon dates49. While a re-assessment of the archeological data has shown that agricultural and fishing communities inhabited Niani at several points during the last two millennia, the excavations did not deliver any of the artefacts one might expect to be associated with elite Muslim traders (coins, glazed ceramic, other imports or exports, etc.), nor did they yield any dates around the 14th century, rendering it extremely unlikely that Niani was the imperial capital.

Fig. 3 Main hypothetical locations of the capital of Mâli (after FAUVELLE, François- Xavier - Les Masques et la mosquée. Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2022, p. 263).

The frantic quest to find the imperial capital of Mâli was fueled by the desire to reconcile a documentation divided in nature. Yet, in doing so, it has failed to recognize that such a division need not necessarily be reconciled. To the extent that the imperial capital of Mâli was where foreign and local merchants, clerics, courtiers and royal officers settled, and hence the one known to Arabic writers, it may not necessarily have been well known in the Mande. Furthermore, the quest to find the imperial capital of Mâli may have led scholars to overlook crucial aspects of the question of the imperial capital of Mâli. One of these crucial aspects is its commercial ambivalence. Just as the capital was where the king publicized his dual political legitimacy, it was probably also where trade between foreign and west African merchants was conducted. In many other regions of Africa, major medieval African powers can be seen as “broker states” who developed an artful diplomatic, fiscal and narrative agency that allowed them to facilitate commercial transactions between economic partners otherwise unknown to each other, transactions which they closely controlled and benefitted from, until they lost them to competitors50. For instance, the city-state of Kilwa probably never extended much beyond the tiny island of Kilwa Kisiwani (in present-day Tanzania) and certainly did not have direct access to the Zimbabwean goldfields, hundreds of kilometers inland; yet it nevertheless managed to dominate the gold trade along the Swahili coast in the 14th and 15th century. Other city-states further north along the coast, such as Mombasa (Kenya) and Mogadiscio (Somalia), served a similar function at the juncture between land and maritime trade networks. The situation was no different in 11th-century West Africa: al-Bakrî describes several city-states along the Senegal River and explicitly states that the king of Ghâna levied taxes on all goods entering or leaving his city51. This implies that the monarch had the authority to cajole merchants from both sides - i.e., the Arab-Berber trans-Saharan network and the Soninke-Malinke West African network - into meeting and conducting trade under his brokerage. It is interesting that the site of Koumbi Saleh in the extreme south of present-day Mauritania, the probable location of Ghâna City - or rather, the Islamic component of Ghâna City - is found in the region of Aoukar, an arid environment in the southern Sahara52. It is likely that the climate change over the last millennium has made the region less hospitable than it used to be; in any case, Koumbi Saleh never enjoyed a fertile, densely populated environment in the same way as “capitals” in other parts of the world. Rather, like the capitals of other medieval African polities - whether situated along the mangrove coastal ribbon of East Africa, or at mid-height of the escarpment of the Rift in Ethiopia -, the capital of Ghâna was a unique commercial “hub”: it filled this role not despite, but because it was situated on an ecological threshold, at a point of juncture between different physical environments, methods of transportation (camels versus donkeys), and ethnic, linguistic and religious faultlines53.

I admit it is counterintuitive to think of Mâli as a broker state, not the least because its vast extent seems to make it the opposite of a “city-state”. It is indeed tempting to believe that the king of Mâli had direct control over the “gold that is collected in his land”, as stated on the Catalan Atlas. But it is just as conceivable that the claim to directly control the goldfields, wherever they were54, was exactly what the kings of Mâli wanted merchants from the Islamicate world to believe, reality notwithstanding. Indeed, when asked in Cairo by a Mamluk dignitary about how tightly he controlled the people who inhabited the region where gold came from, Mûsâ replied that:

“They are uncouth infidels. If [he] wished he could extend his authority over them but the kings of this kingdom have learnt by experience that as soon as one of them conquers one of the gold towns and Islam spreads […] the gold there begins to decrease and then disappears […]. When they had learnt the truth of this by experience they left the gold countries under the control of the heathen people and were content with their vassalage and the tribute imposed on them”55.

This sounds like an oblique admission that the best the kings of Mâli could hope for was to broker commercial ties between “Infidels” and Muslims. This should not be seen as a way of downsizing their sovereignty over an immense territory stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Niger bend in the east; on the contrary, such a tremendous effort was necessary to counter any temptation their northern and southern clients might have had to bypass them and “go private”, as well as to head off any moves by competing regional powers to usurp their role.

The imperial capital of Mâli: Downstream, not upstream, from Ségou

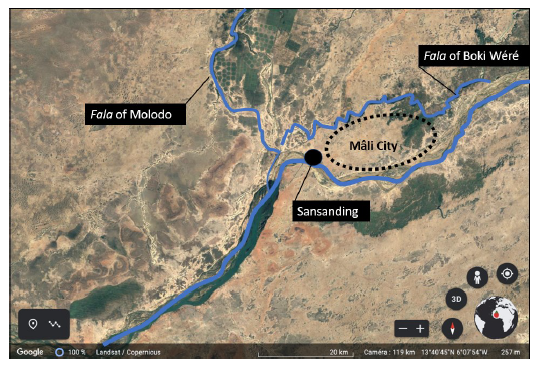

The example of Ghâna City, and the fact that Mâli was the heir to Ghâna in the western Sahel, leads us to suggest that the imperial capital of Mâli might well have been situated in a peripheral, if not exactly outlying, location vis-à-vis the royal domain. The hypothesis proposed in this section places it outside of the present-day Mandika-speaking area, at a linguistic crossroads between Bambara, Berber, Fulani and Soninke speakers. Though not very far from the previously hypothesized locations between today’s Bamako and Ségou, it is further north - which makes it the northernmost location hypothesized so far (fig. 4). If the location of the “City of Mâli” on the Catalan Atlas is any indicator, then my hypothesis matches it by situating the capital on the left bank of the Niger, upstream from Timbuktu. This hypothesis is based on parsimonious reading of the Arabic sources which makes only two minimalist assumptions: first, that if Ibn Battûta did not mention crossing the Niger river we should take him at his word; and second, that if he did not give an estimate of the distance he traveled after reaching the river it is because he had not traveled far56.

Fig. 4 Proposed reconstruction of Ibn Battûta’s inbound (from Oualata to Mâli City) and outbound (from Mâli City to Timbuktu) itinerary (after FAUVELLE, François- Xavier - Les Masques et la mosquée. Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2022, p. 282).

Thus, Ibn Battûta would have journeyed ten days from Oualata to a village called Zâgharî: if he travelled at a pace of 30 km per day (as the crow flies), Zâgharî would probably be somewhere between present-day Goumbou and Sokolo. He would have rested there a few days, before heading to another village called Kârsakhû on the left bank of the Niger. I agree with Binger and Hunwick that Kârsakhû must have been somewhere near present-day Ségou - a result of traveling straight between Oualata and Kârsakhû via Zâgharî -, but on the opposite (left) bank57. He would have stayed there for another few days before moving on. He says nothing about his departure from Kârsakhû, save that “[he] arrived at the river Sansara, which is about ten miles [around 20 km] from the capital of Mâlî”. This is where I assume that, since he did not provide a distance, the journey between Kârsakhû and the capital of Mâli must have been a short one. This is also where I depart from previous researchers who argued that he traveled south to reach the capital, which they situated somewhere between Ségou and Bamako. Instead, I think he traveled downstream, that is, northward. That being the case, in one or two days he would have reached the fala of Molodo, technically not a “river” in the sense of a tributary of the Niger, but an outlet running from the Niger, especially during the flood season. This hypothesis offers, I think, an acceptable explanation to the enigma of the “river” that has long puzzled researchers, since the Niger has no tributary on its left side in this region. Ibn Battûta then crossed this outlet on a ferry (he gives the date: 14 Jumâdâ ’l-ûlâ 753, 28 July 1352, i.e., at the beginning of the Niger flood season58) reaching the capital the same day, or perhaps the next one. The capital would thus be situated some 15 kilometers east of present-day Sansanding. It should be noted that this region is almost entirely circled by water, as another fala, the fala of Boki Wéré, runs out of the fala of Molodo, making a curve that converges toward the Niger (fig. 5). Though technically not an “island”, this geographic feature (about 20 kilometers long) corresponds well, I think, to al-Umarî’s description. This is indirectly confirmed by Ibn Battûta, who says he crossed a “big channel” (he uses the Arabic word khalîj that applies well to a fala) when he left the capital after his eight-month stay, for his return journey to Morocco via Timbuktu and Gao. Ibn Battûta’s outbound itinerary also provides an indirect confirmation of his inbound one: after crossing the “big channel” en route to Mîma - although not yet localized, it was probably found in the present-day Méma region - he was obliged to make a stop at a village called Kurî Mansa following the death of his camel. He then dispatched two servants to buy another camel at Zaghârî, the same place he had stayed before, which happened to have been only a two-day journey from Kurî Mansa59.

Fig. 5 Proposed location of Mâli City (after FAUVELLE, François- Xavier - Les Masques et la mosquée. Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2022, p. 278).

I must add that like all other hypotheses on offer, this one has a serious drawback: there are no known archaeological sites in the region between the Niger, the fala of Molodo and the fala of Boki Wéré. Yet, to my knowledge, no archaeological assessment has ever been carried out in the area, and the political situation as of this writing (the early 2020s) has prevented me from even visiting. Once an archaeological reconnaissance is finally undertaken, I suspect that it will uncover a sparse (over 20x20 km), diversified site made up of several components (an Islamic urban settlement with a mosque, a royal palace, other religious and funerary sites); banco structures, unfortunately largely eroded; and an urban mound likely to yield discriminant artefacts such as glazed ceramics, coins, beads, metal objects, and other imports and exports. It is possible that parts of the former multipolar city might have been destroyed by development that has taken place since the colonial period or have been looted. Finally, readers should be warned that both Malian law and international regulations strictly forbid anyone to carry out excavations without first receiving permission from the country’s authorities.