Introduction

Returning home after being discharged from a psychiatric care unit is viewed as hard and challenging (Desplenter, Laekeman & Simoens, 2011). This admission is projected as a confirmation of people’s inability to maintain daily life’s activities, doubting their sense of competence (Roe & Ronan, 2003). Moreover, resuming to everyday life is deemed as difficult due to: (1) lack of a sense of fellowship in the community; (2) feelings of loneliness (Nolan, Bradley & Brimblecombe, 2011); (3) disturbance in the sense of self (Roe & Ronan, 2003); (4) stigma associated to a psychiatric admission and consequent risk of discrimination (Loch, 2014); (5) failure to be self-supporting; (6) need for social supplementary sources of income; (7) lack of a daily structure; and (8) the need to take medication (Nolan et al., 2011).

Therefore, this particular situation of returning home after being discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit represents a transitional challenge to which the individual has to answer. Furthermore, health care providers should also ensure appropriate care and treatment recognizing it as a moment that requires specific intervention, namely from Mental Health Nursing (MHN). The commitment that MHN has towards the promotion of mental health through the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health issues, leads to the development and implementation of interventions that focus on achieving recovery-oriented outcomes (American Nurses Association, 2014). However, to improve nursing care provided to patients, in a person-centred framework, it is important to gain insight over the experiences of those that lived through this particular transition.

Hence, it became well-timed and necessary to produce a broad scoping review of the available literature, to facilitate the mapping of relevant literature and provide more knowledge and comprehension about the adults’ experiences of such event. With this awareness, it is possible to contribute to the development of priorities and interventions that are more suitable to the needs and wants of the patients after hospital discharge.

In light of the above, the objectives which we aimed to accomplish were: (1) to identify, examine and map the range of adults’ experiences in their return home after being discharged from an acute psychiatric care unit; (2) to produce a summary of results of all relevant literature.

A preliminary search was conducted in order to assess if there were any systematic or scoping reviews on this subject, revealing not to have been accomplished so far. The search included the Joanna Briggs Institute Library of Systematic Review Protocols, Joanna Briggs Institute Library of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, PROSPERO and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects.

Methods

We decided to perform a scoping review for its appropriateness in providing a broad view of the knowledge that was published so far. We adopted the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), which entails five steps:

1- Identifying the research question. The research question is: “What is known from the existing literature about the adults’ experiences of returning home after being discharged from an acute psychiatry care unit?”

2- Identifying relevant studies. The inclusion criteria defined were: studies that investigated the subjective experiences of adult patients that re-entered the community, more specifically home, after being discharged from an acute psychiatric care unit; studies that included participants with 18-65 years old, with any type of mental disorder (except cognitive disability or dementia), gender, culture, and ethnicity. Studies with other age groups (e.g. older people), with any military/army/veteran population, homeless people, forensic or long-stay patients (that are related to a deinstitutionalization process), or discharged to another care facility, were excluded to avoid additional heterogeneity that comes from other circumstances, particular to certain groups. This review considered original studies or literature reviews of any stated research design, written in English or Portuguese, due to feasibility reasons. Opinion papers were not included. Also, we only considered articles whose results included data collected after discharge from the psychiatric inpatient unit. The databases used to find relevant literature were: Academic Search Complete; CINAHL Plus with Full Text; ERIC (Education Resources Information Center); MEDLINE Plus with Full Text; MedicLatina; Scielo (Scientific Electronic Library Online); Scopus; RCAAP (Repositório Científico de Acesso Aberto de Portugal). Additional records were identified through an assessment of the reference list of the articles elected to full text reading and a search for unpublished studies in the site of the European Federation of Associations of Families of People with Mental Illness (EUFAMI) and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

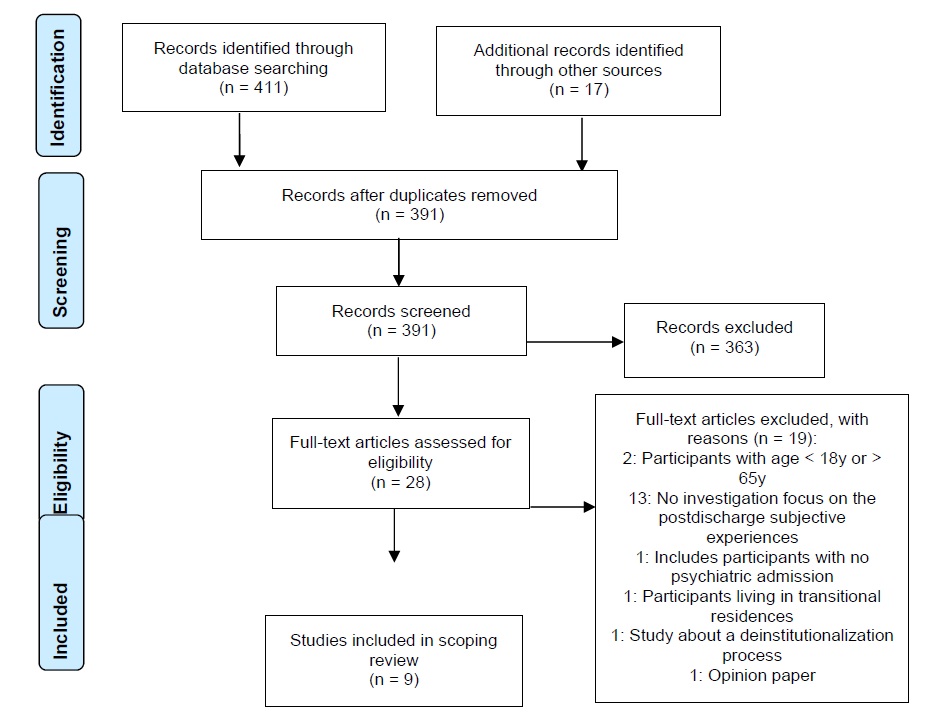

3- Study selection. A three-step search strategy was used in this review (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015). An initial search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was undertaken, followed by an analysis of the text contained in the title and in the abstract, and of the index terms used to describe the article. Initial English language keywords used were: Adult*, Experience*, Discharge, Home, Mental. A second search using identified keywords and index terms based on the Population-Concept-Context framework was accomplished across all included databases. In all the databases a very thorough process of knowing and understanding how each one operated was implied in order to optimize the search results (For more details see http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/xpsmgd9k65.1). Thirdly, the reference list of all identified articles for full text screening was searched for additional studies that directly described patient’s experiences of returning home after psychiatric discharge, as well as for unpublished studies in EUFAMI and NAMI. First of all, the choices made in the selection of studies were made independently by three of the authors, and secondly by a group discussion. No initial date limit was placed on databases’ searches because it allowed to assess the evolution of the topic under review. The databases searches were made up to 17th of March 2018. In two primary studies it was necessary for the reviewers to contact the authors, John Cutcliffe and Peter Nolan, for further information regarding the age of their participants. We got a reply that allowed us to include these studies. There were three studies that were not included, as they did not fulfill the protocol criteria for this review, but may provide some insight to the phenomena of interest to this scoping. These studies were: Niimura, Tanoue & Nakanishi, 2016; Desplenter et al., 2011; and Roe & Ronan, 2003. For that reason they are included in the discussion. For more detail on the selection process, please see diagram in Figure 1.

4- Charting the data. We have compiled the information of the included studies in a data chart form according to: Author(s)/Year of publication/Country of origin; Aims/purpose; Study population and sample size; Methodology/Methods; and Key findings (that relate to the scoping review question). Chart available in http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/xpsmgd9k65.1.

5- Collating, summarizing and reporting the results. This section features a narrative summary of the relevant studies, thematically organized around the experiences portrayed by the studies’ participants.

Results

A total of 9 articles fitted the inclusion criteria pertaining to 8 original studies, as result of two articles being part of the same study. Their publication dates range from 1998 to 2017 and all are from developed English speaking countries: Canada (n=4); United Kingdom (n=4); Republic of Ireland (n=1). This final set of articles represents a total of 121 participants (54 men and 67 women) aged 18-65 years old, with a set of diverse characteristics, such as number of psychiatric admissions or psychiatric diagnosis (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, affective disorder, personality disorder, anxiety, and depression). Two articles focused on chronic patients, three articles highlighted patients with a history of self-harm or suicidal behavior/ideation, and one study focused on individuals with personality or mood disorder. All of the articles are qualitative studies even though presenting different approaches. From these, we were able to establish ten thematic categories whose description we entail below.

Dealing with an unsteady emotional path

All of the papers featured an element of fearful expectation in returning home. The inpatient environment is often considered a shelter that provides for all the basic needs, facilitates human interaction, gives comfort, and provides safety (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017). Reports of negative emotions were spread out through the literature as some dreaded or disliked the perspective of returning to the same stressors of everyday life (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999; Cutcliffe et al., 2012a), while others expressed a sense of powerlessness, uninvolvement or disappointment returning home because they did not feel involved in the decision making of their discharge (Owen-Smith et al., 2014). So there are people that feel under or unprepared, expressing anxiety, fear, being upset and sometimes having a recurrence of their psychiatric symptoms (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Keogh, Callaghan & Higgins, 2015; Redding, Maguire, Johnson & Maguire, 2017).

For those that felt prepared, a sense of elation, optimism and hope embodied their experience, as this return home meant a fresh start for their lives. Nevertheless, continuous contact with reality gradually suppressed those feelings and the everyday problems became a bigger focus, contributing to a sense of vulnerability (Montgomery & Johnson, 1998; Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2017).

For this reason, discharge is viewed as a process and not a clinical point, with a certain degree of emotional hurdles, because it implies time and a gradual complexity that starts weeks before leaving the hospital, building up towards the release day and continuing throughout community support, meaning you are well enough to leave the hospital, but you are not cured (Redding et al., 2017).

Living with a lurking mental illness

As negative feelings and emotions become more present, so does the chance of recurrence of mental illness. In Cutcliffe et al.’s study (2012a, 2012b), the participants left the hospital still feeling suicidal (but not in crisis) and for some there was an increased sense of hopelessness. Participants’ narratives suggested that their suicidality was far from resolved because of the uncertainty of being capable to cope without the help provided by the hospital. The subsequent distress of not coping, resulted in attempting suicide, drinking or overmedicating (Redding et al., 2017). In Owen-Smith et al.’s study (2014) in addition to the reports of suicidal feelings, two participants actually presented self-harm behaviors. In Redding et al.’s study (2017) a readmission occurred a few weeks later. Therefore, the perception of a possible re-admission lurks around as the recurrence of mental illness is viewed as a latent prospect (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999; Redding et al., 2017).

Readjusting to everyday life

It is clear that the experience of readjusting to everyday life is set in motion. It is challenging, time consuming and involves different adjustments. This process becomes harder by the cumulative effect of multiple or long admissions, taking a toll on multiple aspects of life, such as relationships, establishing a daily routine, or getting organized (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017). The experience of readjusting to everyday life found several manners of coming to be, such as trying to restore the activities and relationships to the same level as they were previously to hospitalization (Cutcliffe et al., 2012b), staying busy (Cutcliffe et al., 2012b; Redding et al., 2017), or coming to terms that life would not be the same because there was a sense of loss, sometimes in a very tangible manner through losing a job, being unable to retake a hobby, or regaining independence (Montgomery & Johnson, 1998; Redding et al., 2017). Some participants verbalized experiencing the world for the first time because after adapting to the inpatient world, the return home was like re-learning to live at home (Redding et al., 2017). So, they felt pressured to return to life’s usual pattern, by themselves or the family, (Redding et al., 2017) revealing difficulties in dealing with the responsibilities towards the children or the house chores (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017). Coping strategies as hiding, sleeping, self-medicating, using drugs or alcohol were employed in order to avoid facing the world and endure, bear or numb life in the community (Cutcliffe et al., 2012b). Other participants spoke of settling to a solitary life caused by having been in an environment that’s protective and has all of the needs secured, including companionship from other service users (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017). Therefore, struggling to establish or structure a daily routine (what to do with time), especially in the immediate postdischarge period (Nolan et al., 2011; Birken & Harper, 2017), comes with the expression of uncertainty about themselves and what to do with their lives (Cufcliffe et al., 2012b). Hence, some organized their life around the psychiatric world and its spaces with a sense of resignation towards the illness’ consequences, particularly in people with chronic schizophrenia which experienced discharge not as new beginning but rather as a phase of a cyclic circle that alternates between hospital and community (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999).

Dealing with recurring difficult contingences

Across all of the included articles, returning home was also experienced as returning to the same life stressors, the same difficult contingences that made life harder, hampering prospects of recovery. The stressors reported included feelings of loneliness or isolation (Cutcliffe et al., 2012b; Keogh et al., 2015; Birken & Harper, 2017). For those that lived alone there was a greater sense of vulnerability and isolation because of the absence of constant support provided while in hospital (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017). There is also an interest in keeping in touch with the ward, visiting or doing voluntary work, in order to diminish loneliness (Nolan et al., 2011). Furthermore, compromised familiar and friendship relations, with a gradual decrease of the social support network and increase in feelings of loneliness, rejection, and of being a burden were voiced (Owen-Smith et al., 2014, Keogh et al., 2015; Birken & Harper, 2017). This became more evident when participants were faced with unemployment, inoccupation, inability to resume activities done in the past or to establish long term goals (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999; Nolan et al., 2011; Birken & Harper, 2017). Financial difficulties also emerged as an obstacle (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017) since the illness’ symptoms affect one’s ability to earn money and get a job (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999). Consequently, with less money their living conditions worsen, which in turn affects health and symptom management (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999).

Facing social stigma and discrimination

The sense of stigma and discrimination does not come only from others but also from oneself. In Keogh et al.’s study (2015) the participants had prior negative assumptions about mental illness that changed in light of their hospitalization, in a sense that they were reinforced by health professionals during their inpatient care. The consideration of mental illness as a lifelong and life limiting condition, as something to be ashamed of, to feel guilty or to be hidden hampers self-esteem and self-concept (Cutcliffe et al., 2012a; Keogh et al., 2015). Reports of feeling judged, shunned, misunderstood, and labelled by others due to having a mental illness is voiced, as well as consequent feelings of rejection (Keogh et al., 2015; Redding et al., 2017). Careful disclosure is a strategy described, which can go from omitting or changing some of the details of your story, to being able to defy negative preconceived expectations with talking openly and owning in full this part of your life (Cutcliffe et al., 2012a; Keogh et al., 2015; Redding et al., 2017).

Valuing meaningful relationships

Significant relations are viewed as highly valuable sources of support. This can be provided by family, friends, other service users, or health and social professionals (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Keogh et al., 2015; Redding et al., 2017). This type of support increases the sense of safety, well-being, and hope (Cutcliffe et al., 2012b). It implies an authenticity, longevity and regularity because it is considered that relationships take time to build and gain meaning (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2017). Having a broader network of social support was not considered so important (Owen-Smith et al., 2014).

Being supported by health services

There is a variety in the perception of the amount of support received. For many participants there is a lack of support in contrast to all the support received during admission (Nolan et al., 2011; Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2017), where there was a sense of camaraderie and optimism (Nolan et al., 2011). In Owen-Smith et al.’s article (2014) informants felt that there was no intervention from the staff to get them ready for the psychological impact of being discharged.

The support after discharge can be limited to a prescription (Redding et al., 2017), a postdischarge telephone call from the ward staff or a visit from a crisis team, which is sometimes considered pointless, or done by a community psychiatric nurse or specialist social worker, which in contrast is quite liked and considered important (Nolan et al., 2011; Owen-Smith et al., 2014). The postdischarge support from the mental health professionals and the patient’s involvement in the decision making is much appreciated and constitutes a source of security (Cutcliffe et al., 2012b). Some participants spoke about not feeling valued when they reach out to a service and don’t get an answer or when they sense that are becoming a drain on the service (Redding et al., 2017). Others feel that these services are a privilege that they do not deserve, having difficulty in asking for help (Cutcliffe et al., 2012a; Redding et al., 2017). Sometimes only in crisis would they contact the services (Redding et al., 2017).

Medication compliance

Medication compliance is perceived in several manners such as: essential, because it helps to manage symptoms; useless, because it does not respite difficulties; impairing, because of the side-effects such as sedation or slurred speech; or numbing, for it helps to forget problems, sometimes through self-medication or the use of other psychotropic substances (Nolan et al., 2011; Cutcliffe et al., 2012b; Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2017). One article states that the immediate postdischarge period is where medication is more difficult to manage (Birken & Harper, 2017).

Managing hospitalization effects on identity

The meaning of hospitalization, illness, or the effects of medication can influence one’s identity (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2017). These influences create a sense of not being normal and the need to balance between what the participants feel as normal and the expectations of others (Redding et al., 2017). There is a questioning about the identity and the ability to fulfil the roles you used to have, since participants feel they are not able to fulfil them as they did before (Redding et al., 2017).

Awakening recovery

Two articles briefly brought up recovery as part of the experiences of returning home after discharge. Health and illness are part of a continuum (Redding et al., 2017), and discharge means you are no longer a patient and made some progress (Cutcliffe et al., 2012a). However, recovery is a continuous effort involving challenges and changes, requiring self-responsibility in order to achieve it (Cutcliffe et al., 2012a; Redding et al., 2017). A battle metaphor is used as if mental illness was life-threatening and something you had to fight, defeat and conquer, needing more than just medication to obtain recovery (Cutcliffe et al., 2012a; Redding et al., 2017).

Discussion

The findings of this study bring to our awareness the challenges and hurdles that individuals face in their return home after an inpatient mental health admission. Even though in the general scopus of the articles, psychiatric hospitalization is valued as beneficial, in the sense that the participants feel better than before, it causes a disruption to the lives of the patients (Niimura et al., 2016). This returning to the place that is familiar and therefore expectedly easy, can have a pervasive effect not only on the patients, but also for those around them, including mental health professionals. Assuming that returning home is simply a good thing can devoid the suffering that patients face in coping with daily life, or even create a sense of false expectations that later on will have to be faced and confronted with the reality (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2017).

Discharge is depicted as a process involving more than the formal moment of leaving the hospital with all the paperwork and professional instructions implied. It is a complex transition as patients are prompted to manage their lives autonomously, readapting to daily living, after being in a psychiatric service which provided a very structured and supportive environment (Roe & Ronan, 2003; Desplenter et al., 2011). For some participants this discharge had even a fresh start nuance, sensing hope and optimism towards the future, something that Lorencz (1991) refers to as anticipating mastery towards the community environment, by perceiving the immediate future as a new beginning. It is noteworthy that, this study, is based on four patients with chronic schizophrenia, of which three felt like this towards discharge. Only one of the participants resonates with this reviews’ study of Johnson and Montgomery (1999) in which discharge did not have such a feeling of restart or beginning.

The community and hospital settings blended to compose a quotidian space for these chronic patients and alternating from home to hospital becomes more of an expected habit than a last resort exception (Johnson & Montgomery, 1999). In short, having several or long admissions contributes to a harder adaptation to daily life (Owen-Smith et al., 2014; Birken & Harper, 2017).

Therefore, it is quite revealing that there can be such an array of experiences towards discharge. This contributes to a question, already presented by Johnson and Montgomery (1999), about the influence that particular characteristics of patients, for example their diagnosis, their number of admissions, their social and economic conditions, their age group, their community characteristics, etc., can have on the experiences of returning home after admission to a psychiatric service. Recent evidence supports that variables such as age, gender, and stage of recovery have the ability to alter the experience and manifestation of needs (Davies, Gordon, Pelentsov, Hooper & Esterman, 2018). Indeed, this opens up research development possibilities in order to study this specific experience in particular groups. Other articles seem to follow this lead like Cutcliffe et al. (2012a, 2012b), focusing on participants with suicidal ideation and/or a lifetime history of suicidal behavior in which discharge invoked feelings of fear, anxiety and stress.

The reported lack of involvement in the discharge planning or the postdischarge care, with some interventions being regarded as useless by service users, should inspire health professionals to establish systematic interventions that ensure a collaborative, person-centred and suitably-paced approach that favors a positive view of the discharge process and a continuum of care (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016). Moreover, the higher costs of many patients with mental illness is driven by psychiatric hospital admissions, which in itself justifies the priority investment in transitional interventions between inpatient settings and the community contexts (de Oliveira, Mason & Kurdyak, 2020).

Mental health nurses can have a pivotal role in this crossover, as they are aware that regardless of the source for the transition, its progress may be mediated by the environment’s support provided (Meleis, 2010). The establishment of therapeutic relationships in a collaborative partnership taking into account the individual’s choices, experiences, and circumstances is a valuable contribute that mental health nurses can provide.

Finally, this scoping review has illuminated the experiences that adults go through when leaving a very specific care setting, the psychiatric hospital/service, to go home. Even though the review presented here was limited to English and Portuguese literature we consider that relevant computer bibliographic databases were searched allowing to obtain a scope of the scientific literature developed so far. Indeed, we consider that more research on this subject has to be developed, as our results are based on a small number of participants that are only from English developed western countries, lacking the necessary representability, as many regions of the world are not reflected here. As no critical appraisal of the quality on the included studies took place, implications for practice are limited.

Conclusions

The return home after a psychiatric hospitalization constitutes a complex progression that requires deliberate transitional care that embraces a person-centred approach, with recovery-oriented goals, that provide a collaborative discharge planning sensitive to the subjective experiences and consequent needs, expressed by the clients, bearing in mind the personal contingencies, the environmental context, the stigma and discrimination that still lingers on the experience of those who have to face a psychiatric admission.

By knowing the patients’ experiences, during this period, it is possible to confirm the need for preventive and therapeutic interventions, that confer to the hospitalization and the inherent discharge planning, the opportunity to address the stressors and triggers that bring about mental ill-health disturbance, which is an area that lacks visibility in the experiences related by the included studies.

Mental health nurses are in a key position to help service users gain a more central and active role in their recovery, facilitating the resources and the support that enables them to achieve autonomy and independence to the best of their potential. People who live alone or share feelings of loneliness, and people that lack social or financial support, should be acknowledged and have the necessary support from community and mental health services, as they are more likely to face stressors that can undermine recovery. The establishment of meaningful relationships is also of extreme relevance in the wellbeing and sense of belonging of people that go through this transition, with mental health or social professionals supporting the development of strategies to fulfill these requirements if needed, with focus on the immediate postdischarge period. This scoping review clearly shows that this means more than symptomatic remission, with mental ill-health issues implying a very deep and personal meaning, to which all health and social professionals must be open and sensitive to.

The need for developing further research in this subject is also present, namely towards research in non-English speaking countries and particular cohorts of participants as it is possible that different, particular, or new experiences may arise, like for example, looking into individuals with a first admission, or people with a particular diagnosis or age group.