Introduction

More and more people talk about mental health in our society, and at an opposite pole more and more mental illness has an added social weight. However, it is difficult to find properly structured and validated programs for the promotion of positive mental health aimed for adults based on a well-founded theoretical model (Teixeira, Coelho, Sequeira, Lluch I Canut, & Ferré‐Grau, 2019).

It is possible to find some mental health, well-being, or resilience promotion strategies aimed at adolescents in the field of school health, especially in countries like China, Australia and Canada (Antezana et al., 2015; Anwar-Mchenry, Donovan, Jalleh, & Laws, 2012; Chen et al., 2020; Cheng, Tomson, Keller, & Söderqvist, 2018; Gilmour, 2014; Love, Nelson, Pancer, Loomis,& Hasford, 2013; O’Connor, Sanson, Toumbourou, Norrish & Olsson, 2017; Orpana, Vachon, Dykxhoorn, McRae, & Jayaraman, 2016).

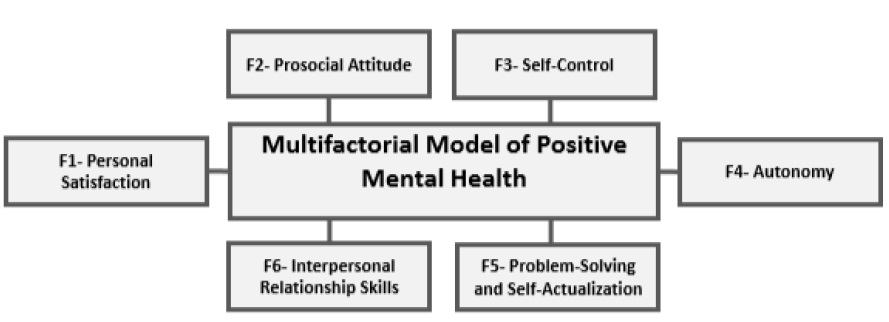

Promotion brings health benefits to societies, and there is even evidence that positive mental health grants, for example, resistance against suicidal ideation (Teismann, Brailovskaia, & Margraf, 2019). We need to stay healthy and optimize as much as possible the favorable aspects of the human being. In this sense, the WHO (2004) also supports this need and defines positive mental health as "a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community." Marie Jahoda's initial approaches were extended by the conceptual and metric work of Teresa Lluch in 1999 and subsequent years. Lluch (1999) elaborated the Multifactorial Model of Positive Mental Health (MMPMH), configured by 6 factors: Personal Satisfaction (F1), Prosocial Attitude (F2), Self-control (F3), Autonomy (F4), Problem-solving and Self-actualization (F5), and Interpersonal Relationship Skills (F6).

To evaluate the multifactorial model, she constructed a Questionnaire (Positive Mental Health Questionnaire-PMHQ), made up of 39 items distributed among the 6 factors. The model and the questionnaire have been validated in different samples and contexts with good psychometric and clinical results. Both the conceptual model and the questionnaire have been used to carry out positive, global, and factor mental health evaluations, psychometric studies, and also correlational studies of positive mental health with psychosocial and health determinants (Lluch-Canut, Puig-Llobet, Sánchez-Ortega, Roldán-Merino, & Ferré-Grau, 2013; Hurtado-Pardos et al., 2018; Mantas-Jiménez et al., 2015; Roldán-Merino et al., 2017; Sequeira et al., 2014; Sequeira et al., 2019; Teke & Baysan, 2019). Diagnosis and evaluation of positive mental health are essential, but as indicated above, it is crucial to carry out intervention programs to promote positive mental health. Lluch's work (1999) presents a conceptual model that guides interventions and a measurement instrument that allows pre and post-intervention evaluations (PMHQ). There are some experiences of positive mental health intervention programs using Lluch’s model in specific samples (Ferré-Grau et al., 2019; Puig-Llobet et al., 2020; Sánchez-Ortega, 2015; Sanromà-Ortiz, 2016; Soares De Carvalho, 2018). However, intervention programs that promote positive mental health in adults using this model are non-existent. Therefore, we prepare a proposal of a Positive Mental Health Program for Adults and have experts validate its structural aspects and content.

Our Positive Mental Health Program for adults was initially planned to be taught by specialist mental health nurses. In Portugal, the competences of specialized mental health nursing are regulated by the Specific Skills Regulation of the Nurse Specialist in Mental Health (2011). According to this regulation, mental health nursing focuses on the promotion and prevention of mental health and on diagnosis and intervention concerning reactions resulting from maladjusted or maladaptive human responses to transition processes that generate suffering, alteration, or mental illness. While taking care of a person, a family, a group, and a community throughout the life cycle, nurses develop practical understanding and therapeutic intervention capacities that allow them to promote and protect mental health, to prevent mental illness, and to contribute to psychosocial treatment and rehabilitation. Furthermore, the regulation emphasizes that nurses who specialize in mental health shall provide person-centered care throughout the life cycle, in professional contexts, in the hospital, and the community.

Accordingly, we consider that the creation and validation of a program for the promotion of positive mental health in the Portuguese population, based on the Multifactorial Model of Positive Mental Health by Teresa Lluch, is of great pertinence.

Methodology

Aims:

In this study, we aim to enable the adaptation of the six-factor theoretical model (Lluch, 1999, 2003) of positive mental health in a practical intervention program that, together with the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire (Sequeira et al., 2014), can guide nurses and other health professionals in the promotion of positive mental health.

Design:

We followed the methodological guidelines proposed by Krueger and Casey (2014). The focus groups involved 7, 10, and 6 participants per group, engaged in semi-structured discussions about the program structure, the inclusion criteria, the conceptual composition of the sessions, and the effectiveness of the program (figure 1). We developed a semi-structured focus group discussion guide. The duration of the focus group meetings ranged from 60 to 120 min.

Participants:

A total of 23 experts participated in the three focus groups, after being selected by intentional non-probabilistic sampling. The participants are investigators of the Research Group NursID: Innovation & Development in Nursing, of the Center for Health Technology and Services Research (CINTESIS). We asked the researchers to participate by sending them an email with the invitation.

All the experts selected met at least two of the following five selection criteria: (a) is a professional with training and specialization in mental health and psychiatry, (b) holds a master's or a doctoral degree, (c) has been working in health institutions for at least 5 years, (d) is a professor in nursing schools/universities, (f) is familiar with the concept and the Multifactorial Model of Positive Mental Health.

None of the invited experts declined the invitation or withdrew from the study. Only participants and researchers were present in the focus group.

Data Collection:

The data in this study were collected at the Nursing School of Porto. The data concerning the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample were collected using an ad hoc constructed form. For the validation of the Positive Mental Health Program for Adults, a semi-structured interview script was used, with the following four topics: 1) structure of the program: we proposed to work with the Multifactorial Model of Positive Mental Health-MMPMH (Lluch, 1999); specifically we suggested that each factor was addressed in 3 sessions of 1h each and that each session had at least 2 and no more than 12 participants; 2) inclusion criteria of participants; 3) conceptual composition of the sessions; 4) effectiveness of the program.

Ethical Considerations:

Participants' confidentiality was guaranteed. All participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any moment. All participants gave their consent. Ethical approvals to conduct the study were obtained from the Ethics Commissions of the Nursing School of Porto (ESEP) and the Center for Health Technology and Services Research (CINTESIS).

Data analysis:

For qualitative analysis, the discussions were transcribed, with the aid of audio. The data was analyzed immediately after each focus group meeting was finished. No software was used for data analysis. Participants did not provide feedback on the results, as the analyzed data was not returned to them for comments or corrections.

Validity and reliability:

The expert meeting began with the PowerPoint presentation of the positive mental health program for adults. Afterward, the sociodemographic characterization of the participants was completed.

The focus groups carried out were always conducted by two researchers. The investigator (SMAT) directed the focus groups, clarified the objective, presented the positive mental health program for adults, and encouraged/registered the exchange of opinions, while the second investigator (CS) managed the dynamics of the group.

The focus group discussion was based on the following questions, symbolically presented as the “anxieties” in the construction of the program: 1) Did you agree with the following mandatory inclusion criteria for adults in the Positive Mental Health Program? 2) The proposed program lasts at least 7 weeks (1h session per week). Did you agree? 3) 2 initial sessions of 1 hour each will take place. Did you agree? 4) 3 sessions (A, B, C) per factor/dimension will take place, with a duration of at least 1 hour. Did you agree? 5) Can the program work individually or in groups (2 - 12 persons maximum)? 6) The first contact (initial session) with the participants will be individual or in group, depending on the professional context, 1 week to 1 month before the program starts. Did you agree? 7) Did you agree with the objectives of the 1st session (group or individual) and the objectives of the 2nd (individual) correlating with the description of the sessions activities? 8) After application of the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire and detected greater vulnerability in factor F1- Personal Satisfaction will be realized 3 group sessions. Did you agree with the objectives correlating with the description of the session’s activities? 9) After application of Positive Mental Health Questionnaire and detected greater vulnerability in factor F2 - Prosocial Attitude will be realized 3 group sessions. Did you agree with the objectives correlating with the description of the session’s activities? 10) After application of Positive Mental Health Questionnaire and detected greater vulnerability in factor F3 - Self-control will be realized 3 group sessions. Did you agree with the objectives correlating with the description of the session’s activities? 11) After application of Positive Mental Health Questionnaire and detected greater vulnerability in factor F4 - Autonomy will be realized 3 group sessions. Did you agree with the objectives correlating with the description of the session’s activities? 12) After application of Positive Mental Health Questionnaire and detected greater vulnerability in factor F5 - Problem-solving and self-actualization will be realized 3 group sessions. Did you agree with the objectives correlating with the description of the session’s activities? 13) After application of Positive Mental Health Questionnaire and detected greater vulnerability in factor F6 - Interpersonal Relationship Skills will be realized 3 group sessions. Did you agree with the objectives correlating with the description of the session’s activities? 14) Did you agree with the objectives of the final (individual) session and the objectives of the follow-up session (individual) correlating with the description of the sessions’ activities? 15) What would you change in this program? Suggestions.

Results

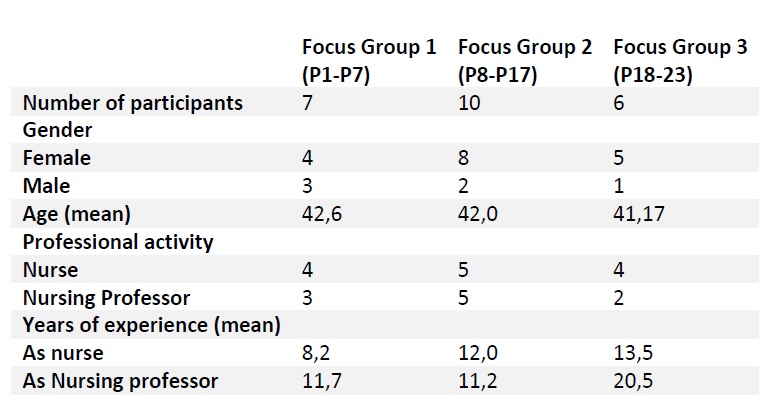

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the focus group participants (n = 23). Verbatim quotes from participants were used as examples at the presentation of the results. The usage of coding allowed to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Structure of the program:

All participants agreed on the importance of having a theoretical, conceptual model to build the positive mental health program for adults. In addition, they agreed on choosing the Multifactorial Model of Positive Mental Health (Lluch, 1999) (Figure 2).

A good model that represents positive mental health is Teresa Lluch’s. (P2)

There are many models in the mental health area, but when we talk about positive mental health, we are talking about Teresa Lluch's Multifactorial Model. (P7)

Although the program is based on a theoretical model, the participants attributed great relevance to the fact that it has a practical character,

Operationalizing a theoretical model for clinical practice will help many nurses and other health professionals interested in promoting positive mental health. (P4)

Despite the intense discussion, a consensus was reached about the number of sessions per factor. After the discussion, the conclusion was reached that the program would need to have a watertight character. That is, it will inevitably need to have a beginning and an end in order to be concluded. However, if besides the three sessions previously established per factor, the health professional concludes in the final evaluation that more sessions are necessary, he/she will be able to work with the participant after the conclusion of the program, in a context of specialized intervention in mental health, using techniques such as the helping relationship, the cognitive restructuring, relaxation, etc.

What if the three sessions are not enough to work self-control, for example? It seems important that we have the chance to continue the program in the last session, even if it is finished. (P11)

Ethically, we should not abandon the person. Even after the end of the program, if the person does not feel well enough, he/she should be given a chance to continue with the program. (P8)

In this follow-up, we included the following activity in the final session: referring participants to the care of a specialist nurse in mental health or another health professional.

It was also concluded that for each session to last 1 hour, the maximum number of 12 persons per group should not be exceeded, or the duration of the session should be established according to the total number of participants.

The larger the group, the more difficult it is to control and give people time to express themselves without being interrupted during the session. (P18)

It is preferable to end the session before the established time than to extend it beyond the established time. (P12)

We also concluded that, in the initial session, it would be ideal to use support health education materials, such as brochures, predefined PowerPoint presentations, support manuals for the full presentation of the positive mental health program, and a promotional video that could be used in various contexts.

It is preferable to have standardized material so that all health professionals can use it identically and thus speak the same language. (P2)

Inclusion Criteria:

The discussion about the criteria for the inclusion of participants was unanimous. However, one of the members of the expert group suggested that besides using the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire to learn what are the factors to work on, the person's opinion should be heard in this regard. The rest of the participants agreed with the suggestion, thus giving relevance to self-criticism and self-awareness about the factors that persons think should be improved and work on that may or may not correspond to those inferred by the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire.

Besides using the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire, we should take into account the person's opinion about the factors to target in the promotion of mental health. (P8)

Conceptual Composition of the Sessions:

The simplicity of the activities in each session gathered consensus. The debate focused on the “anxieties” of being able to build sessions with simple activities for the participants to understand easily, despite the possibility of having elements with different levels of education in the same group.

Still, the discussion concentrated on the sessions that give the participants a homework assignment at the end of the session for them to bring in the next session. Accordingly, it seems that it would be preferable to reserve some time at the beginning of the next session for participants who may forget to do their homework.

In my experience, many people often forget to do their homework. (P8)

What we have done in the activities that we have already done at Pedro Hispano Hospital is to reserve a space at the beginning of the next session to complete the homework, and it works well. (P20)

Effectiveness of the Program:

Finally, with positive mental health as a key concept, experts believe that for the assessment of progress, it is crucial to apply the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire (Sequeira et al., 2014) at the beginning and the end of the program.

Furthermore, they suggest that other psychometric instruments properly validated in Portugal for scientific research are used. As an example, they mention the Mental Vulnerability Scale (Nogueira, Barros & Sequeira, 2017).

It is important to carry out nursing research, so other instruments should be applied to cross-check data in the future. (P8)

Discussion

The results of the study indicate that positive mental health is a theoretical concept that needs to be translated into the practical component.

There are several concepts associated with mental health and used indiscriminately, such as resilience, mental hygiene, mental well-being, etc. (Longo, Jovanović, Sampaio de Carvalho, Karas, 2020; Chen et al., 2020). Regarding the specific area of positive mental health, the theoretical model found while carrying a systematic review on the topic (Teixeira et al., 2019), was Teresa Lluch’s Multifactorial Model of Positive Mental Health - MMPMH.

Therefore, it seems clear to us that the positive mental health program in adults must be based on Teresa Lluch’s (1999) Multifactorial Positive Mental Health Model.

As indicated in the introduction, the selection of the MMPMH model for the construction of the program resulted from a systematic review of the literature carried out in 2019 “The effectiveness of positive mental health programs in adults: A systematic Review” (Teixeira et al., 2019). The review revealed there is no systematic positive mental health promotion program that can be applied in the same way by different health professionals, despite the evidence of health gains in those who participate.

The positive mental health decalogue created by Lluch (2011), does not integrate the positive mental health program, but it was incorporated in the initial session of the program. This decalogue is the product of the “psychology of daily life.” It is the result of a scientific study expressed in specific, applicable terms. Each recommendation is valuable in itself and can be applied individually or together with others. Indeed, the more recommendations we apply to our lives, the stronger our positive mental health will be (Lluch, 2011).

As Mantas-Jiménez et al. (2015) tell us, it is crucial to develop strategies focused on health promotion, given the need to approach interventions to promote people's health in work contexts. However, for this, it is necessary to prepare health professionals in several areas.

It seems essential to conduct courses aimed at training health professionals, namely nurses who are specialists in mental health and psychiatry, for the implementation of the positive mental health program in the various contexts in the community. Some of these contexts may be the school environment (e.g., students, teachers), nursing in sport (e.g., football teams), risk groups (e.g., police forces), occupational health (e.g., factories, hospitals) among others. In the future, this should be the next step.

Another group to address in the promotion of positive mental health is the group of health professionals because it is essential to be well to take care of others. The promotion of positive mental health among these professionals should start at the very beginning in schools and universities during pregraduate education. It is essential to invest in strategies to encourage nursing students’ health during training, allowing them to have better stability against situations imposed by the work, as well as consciousness regarding the importance of care (Ferreira, Cortez, Silva, & Ferreira, 2016).

The positive mental health program may be one of those strategies and tools to be used in promoting the mental health of professionals.

Likewise, the relationship of positive mental health with several variables such as sociocultural, socioeconomic, education and quality of life should be investigated, since such variables can influence the environment of the individual positively or negatively, favoring or hindering the adequate development of the different criteria that support positive mental health (Alfaro, Ocaranza, Watier, Sanhueza, & Barrios, 2019). So, using a sociodemographic questionnaire before applying the positive mental health program becomes essential.

As such, it is critical to systematize the promotion of positive mental health at the community level (Enns et al. 2016) through outlined programs (Marino et al., 2018).

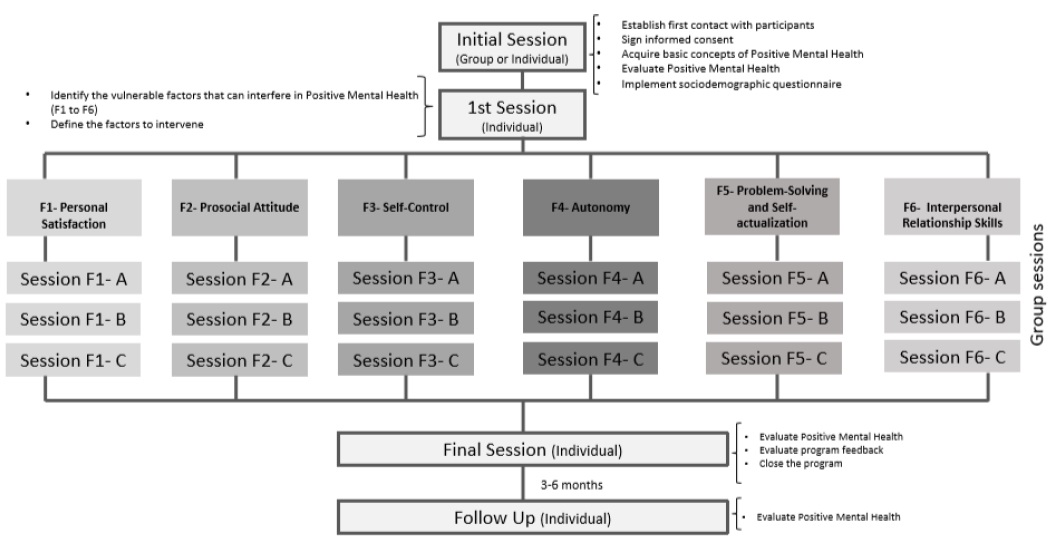

In this positive mental health program (Figure 3), each factor can be considered a module, so it is a modular program, and each module has 3 sessions to be carried out in full.

The modules correspond to the “less well” or “vulnerable factors” identified after the application of the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire. From the moment that the Positive Mental Health Questionnaire is applied and interpreted, the groups of individuals that correspond to the same factor/module can be constituted. Thus, a group of 12 persons maximum is determined to carry out the sessions for the factor/module to address. There will be two initial sessions of one hour each. There will be three sessions (A, B, C) for each factor/module, lasting at least one hour. A final session and a follow-up session (3-6 months post-program) will also take place. The program lasts for 7 weeks minimum and 22 weeks maximum (one session per week, of one hour). The duration of the program depends on the individuals participating. It also depends on the number of factors/modules addressed. This is a systematic program. The order of the sessions is regulated by the letters A, B, and C for each factor/module. The final positive mental health program for adults designated Mentis Plus+ is detailed in the Appendix.

Limitations:

Despite the relevant results obtained in the present study, we faced some limitations. First, the participants were asked only once; we were unable to verify if their opinions were maintained over time. Second, in the future, it is also important to seek consensus regarding the program's effectiveness in more detail, for example, by conducting a Delphi study with professionals who have already implemented the program. Finally, we could not implement a focus group in Spain, where the concept of positive mental health is deeply rooted, even though the author of the MMPMH is directly participating in the study.

Conclusion

In general, the participants identified the objectives of the positive mental health program sessions as relevant, and the duration and proposed activities for each session as appropriate. It will be the health professionals in clinical practice who will dictate the need to implement the program of positive mental health promotion in several contexts of the community. It is imperative to take care of our positive mental health, especially when we face pandemics that put us to the test not only physically, but also psychologically.

Implications for clinical practice

The results of this study have the potential to inform mental health professionals about the availability and creation of a positive mental health program for adults. The study carried out encourages mental health nurses to put into practice interventions resulting from properly validated programs of mental health promotion. It is crucial to carry out intervention programs to promote positive mental health. Intervention programs that promote positive mental health in adults using Multifactorial Positive Mental Health Model are non-existent. So, the Positive Mental Health Program appears to overcome the need for promotion within the scope of Mental Health through a model operated in sessions that can be dynamized by health professionals in a uniform and identical way, through standardized procedures adjusted to individual needs. Furthermore, in order to achieve health indicators and gains in mental health, it is increasingly necessary to have objective and properly validated tools, such as the program, that health professionals can implement without fear. This study reveals a significant strategy to promote positive mental health in everyday life after pandemics.

Author’s contribution

Sónia Manuela Almeida Teixeira was responsible for collecting data and preparing the manuscript (writing). Carlos Sequeira, Teresa Lluch-Canut, and Carme Ferré-Grau were responsible for the scientific supervision of the research and the critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.