Introduction

Delirium is characterized by the acute onset of deficits in attention, awareness and cognition, with a tendency to fluctuate over time (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is also known as an acute confusion, being a frequent nursing diagnosis in intensive care units (ICU) (International Council of Nurses, 2011).

Patients commonly describe delirium as an unpleasant and distressing experience (Breitbart et al., 2002; Bruera et al., 2009). Caring for delirium patient can also be a psychologically distress experience, for the ones taking care of them, like family and health care staff (Breitbart et al., 2002). Psychological distress can be defined as a state of emotional suffering with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Drapeau et al., 2012).

Amongst all healthcare workers, nurses have the most time of contact with these patients, as they are responsible for most of the “hands-on” management of a cognitively impaired patient, as well as their medical underlying conditions (Breitbart et al., 2002; Thomas et al., 2021). Because of this, nurses are at most risk of developing distress after caring for patients who develop delirium.

Previous studies (Kristiansen et al., 2019; Schmitt et al., 2019; Schofield et al., 2012; Soroka et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2021) have reported that nurses caring for delirium patients have frequent feelings of sadness, frustration, and concern for their patients, since these not only are uncapable of proper collaboration in their treatment, but also refuse any attempts of help. Many nurses also feel unsafe and scared, especially dealing with very agitated and confused patients that can turn aggressive or even hurt themselves during a delirium episode. This links to the overall notion that dealing with these patients is very unpredictable in nature, as it is difficult to assess their fluctuating condition. The majority of literature studying the impact of delirium on the levels of nurses’ distress is qualitative. On the other hand, quantitative works are limited, with only a few studies using numeric scales to measure distress and its association with delirium symptoms (Breitbart et al., 2002; Morandi et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2021). Research is even sparser for nurses working in ICU where delirium is very prevalent (Tan et al., 2021; Soroka et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2021).

Bearing this in mind, this study aims to address this gap in the literature by measuring the global levels of distress in ICU nurses related to delirium episode, to specific delirium symptoms and its severity. It also aims to identify nurses’ sociodemographic characteristics, factors related to professional experience and the presence of psychological distress or burnout - that may contribute to distress related to delirium.

Methods

Patient sample recruitment and assessment

This prospective study was implemented with nurses of older inpatients (≥65 years old) consecutively admitted in two level-2 units of the Intensive Care Medicine Department (ICMD) of Centro Hospitalar Universitário S. João (CHUSJ) in Porto, Portugal, between October 2017 and July 2018. Patients were excluded when they presented deafness/blindness, or an inability to communicate or had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of ≤11. All patients were daily assessed, from admission to discharge of ICMD unit, for delirium by research team medical staff, with the European Portuguese version of the Confusion Assessment Method - Short Form (CAM-Short Form) (Inouye et al., 1990), previously validated by this research team. This instrument consists of four items derived from an original longer version, the CAM-Long Form (Inouye et al., 1990), and evaluates the core features of delirium: (1) acute onset/fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) disorganized thinking and (4) altered level of consciousness. A delirium diagnosis is suggested when both (1) and (2) are identified, and either (3) or (4) are present. Delirium severity was assessed using this version of CAM. Each symptom was rated as (0) absent, (1) mild and (2) marked. ‘Acute onset’ or ‘fluctuating course’ were rated as (0) absent or (1) present. The final score ranging from 0 to 19, with 0 being the least severe and 19 the most.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were obtained through chart review and structured clinical interview. Patient’s cognitive state previous to admission was evaluated resorting to the short version of Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE-SF) (Jorm, 1994), a questionnaire filled out by someone who knows the older adult for two years or more. A total score of >3.44 indicates cognitive decline. The level of dependency was evaluated with Barthel Index (BI) (Mahoney & Barthel, 1965), which measures 10 basic activities of daily living (BADL). The following cut-offs were considered: total dependence (0-19), severe (20-39), moderate (40-59), mild (60-89) and independence (90-100). The Lawton Index (LI) (Lawton & Brody, 1969) assesses a person’s ability to perform eight instrumental activities to daily living (IADL). Three categories were assumed: independence (score: 8), moderate (scores: 9-20) and severe dependence (>20).

According to CAM assessment, 41.3% (n=26) of patients developed delirium. The median age of patients with delirium, was 82 years old and most were female (65.4%) with primary school education (62.5%). The median of ICMD length of stay was 19 days.

Regarding the pre-admission cognitive and functional status of delirium patients, 62.5% have no cognitive decline, 62.5% had moderate dependence on IADL, and 79.2% independence in BADL.

Nurse sample recruitment

The nurse who was working on a shift where a patient developed delirium was invited to participate in this study. In the ICMD, nurses are assigned to specific patients and there are multiple nursing shifts ranging from 7 to 11.5 hours. However, the next day they may not be assigned to the same patients. If multiple nurses were responsible for the patient who had a delirium episode, all were eligible to be invited.

Nurse’s distress related to delirium episode

The nurses who participated in this study were asked to identify which symptoms they observed in the patients diagnosed with delirium during their contact with them. This was done by checking them on a list of 11 symptoms derived from the long version of CAM (Waszynski, 2002). For each identified symptom, the nurses were then asked to rate the level of distress associated with each one by rating in a Likert scale of (0), “not distressing”, through (4) “severely distressing”.

The global distress associated with the experience of dealing with a confused patient was evaluated using the Delirium Experience Questionnaire (DEQ) (Breitbart et al., 2002), which includes a Likert scale from 0 (not distressing) to 4 (extremely distressing) to attempt to quantify the degree of distress experienced by nurses. The Portuguese version of the DEQ used in this study was previously validated by the research team.

Additionally, nurses were asked another three questions. The first was if they believe their patient remembers the episode. The second one was if they believe the experience was distressing to their patient. If “yes”, they are asked to rate in a similar Likert scale how distressing they consider it was.

Burnout in nurses

It was assessed using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) (Kristensen, 2005), which evaluates three dimensions of burnout for any cause: personal, work-related, and patient-related burnout. It consists of 12 questions to be answered according to how often the nurses experience those feelings and the answers include “always, often, sometimes, rarely and never” and seven questions to quantify how intense some feelings are, with answers including “to a very high degree, to a high degree, somewhat, to a low degree, and to a very low degree”. Personal burnout pertains to evaluate the physical and psychological exhaustion; Work-related burnout measures the degree of physical and psychological exhaustion associated with their work and Patient-related burnout is related to the physical and psychological exhaustion associated with the interaction with patients. The final score for each subscale is the average of all the answers of that category. A score higher than 50 in each category was considered burnout.

Psychological distress in nurses

It was evaluated with the Kessler Psychological Distress scale (K6) (Kessler et al., 2003). It includes 6 questions focused on the presence of depression and anxiety symptoms in the last month. The total score ranges from 0 to 24, with a cut-off of ≥6 being considered indicative of psychological distress.

Ethical considerations

The current study is part of a larger research project [grant number SFRH/BPD/103306/2014], approved by the Ethics Committee for Health of CHUSJ. All study participants gave written informed consent. A close relative or proxy provided consent for patients who were no capable of providing consent (because of cognitive impairment/dementia or delirium). Nevertheless, consent was obtained from the patients who developed delirium once their condition had its resolution.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as raw frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as a median and range, as normality was not assumed. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between continuous variables. For analysis of differences between the groups of patients, the Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting cohort studies was used as guideline in order to structure this paper.

Results

In what concerns to nurse sample (n=18), most were women (88.9%), 50% married and had a median age of 35 years. Most nurses (72.2%) did not have any specific education/training on with delirium. Based on k6 scale, psychological distress was found in 43.7% of nurses. Work-related and patient-related burnout were both found in 56.2% of nurses (Table 1).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and psychological characteristics of nurses

Note: min.: minimum, max.: maximum; ICMD: Intensive Care Medicine Department; CBI: Copenhagen Burnout Inventory; K6: Kessler Psychological Distress scale; *NR=2

Of the 26 patients with delirium, 22 assessments of the level of distress related to the delirium episode were performed by 18 nurses. The nurses had a median of two shifts with the corresponding delirium patient.

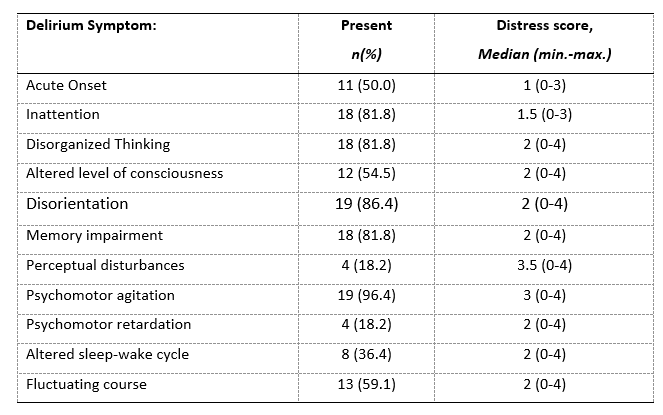

Concerning delirium symptoms, the most reported were ‘Disorientation’ and ‘Psychomotor agitation’. The symptom with the highest median of distress was ‘Perceptual disturbances’ followed by ‘Psychomotor agitation’ (Table 2).

Table 2 Delirium symptoms identified by nurses and associated distress

Note: min.: minimum; max.: maximum

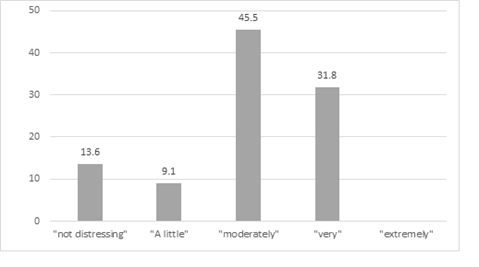

Concerning to the level of distress related to delirium episode, assessed by DEQ, 45.5% of nurses classified the experience as “moderately distressing”. (Figure 1)

In this sample, 78.9% of nurses felt that their patients did not remember the delirium episode. About 58% of nurses considered that delirium was a distressing experience for patients, with 64% classifying that the delirium was “very distressing” to “extremely distressing” for the patient.

Factors associated with distress in nurses related to delirium:

Regarding to sociodemographic and professional characteristics, no significant correlations were found with delirium-related distress in nurses.

In relation to specific delirium symptoms, no associations between the global distress of nurses (assessed by DEQ) and delirium symptoms were found, except for psychomotor agitation (presence vs absence: median DEQ score=2 vs 0; p=0.008; U test= 2.500).

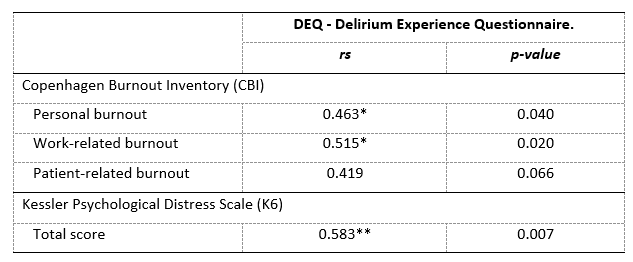

Concerning burnout, significant positive correlations were found between Personal (rs=0.463; p=0.040) and Work-related burnout (rs=0.515; p=0.020) domains, and the global distress of nurses. Also, a positive association with global psychological distress, assessed by K6 scale, was identified in this study (rs=0.583; p=0.007) (Table 3).

Discussion

Caring for a delirium patient was found to be a “moderately distressing” experience for almost half of the nurses included in this study. About 32% reported high levels of distress and there were no nurses expressing extreme levels of distress. These results point to that the delirium experience is distressing even to healthcare professionals who are taking care of the patients with this disorder. Moderate levels of distress appear to be a result to be somewhere in-between of what previous studies using the DEQ have reported. Bruera et al. (2009) found very low levels of distress in nurses, with a median of 0.0, but Breitbart (Breitbart et al., 2002) found higher levels, with a mean of 3.09 (very distressing) and 73% of nurses reporting either high or extreme distress. Other studies (Tan et al., 2021) found levels of distress in nurses that could correspond to a moderately to high degree of distress. Another study (Morandi et al., 2015) also found low levels of distress in health staff, including nurses with a mean of 0.8. Overall, the results are contradictory, with findings ranging from no distress to high levels. These irregularities might stem from nurses’ different approaches, variability of patients, their clinical histories, hospitalization setting, and different study procedures (either in samples of nurses or distress measurements).

Considering delirium symptoms, the ones with higher medians of distress were Perceptual disturbances and Psychomotor agitation. This is in accordance with other studies, with Breitbart (Breitbart et al., 2002) also singling out both of these symptoms as some of the most distressing, and other authors (Tan et al., 2021) finding hyperactive symptoms or behaviours, which have Psychomotor agitation as a defining factor, to be more difficult to handle. Some qualitative studies also describe agitation or aggressive behaviours (Schofield et al., 2012) and hallucinations/perceptual disturbances (Mossello et al., 2020) as key parts of the distressing experience of treating a patient with delirium. Agitation and perceptual disturbances are symptoms that present a big challenge for nurses, as the patient often needs more time and help than before. These can also make it very difficult to understand the patients and nurses often find patients weary of their actions in previously cooperative patients (Kristiansen et al., 2019; Mossello et al., 2020). There is also a possibility of patients becoming impulsive and aggressive towards the staff, because of hallucinations or agitation, making nurses fear for patient’s or their own safety (LeBlanc et al., 2018).

As for the factors that were found to be correlated with the delirium-related distress levels in nurses, assessed by DEQ, the only symptom identified by nurses with a significant association was psychomotor agitation. Although this was not found in prior research, it is an expected association given the studies that mention high levels of distress related to this specific symptom.

Regarding nurses’ psychological characteristics, global psychological distress, as assessed by K6 scale, and work and personal burnout, assessed by the CBI, were positively associated with delirium-related distress. These were expected correlations as nurses’ psychological vulnerability and concomitant distresses could heighten their sensibility to delirium-related distress. A positive correlation with patient-related burnout was expected, as delirium-related distress relies upon nurses having to deal with patients with a difficult disorder, however it was not statistically significant. Another expected association was with delirium severity, has it had been found in a previous study (Breitbart et al., 2002), but it was not found.

Conclusion

This study concluded that treating a patient with delirium is a distressing experience for nurses, particularly if perceptual disturbances and psychomotor agitation are present in during delirium episode and if nurses presented high burnout or psychological distress.

The present study has some important strengths, as it is one of the first that quantify the delirium-related distress in nurses and simultaneously assessing patient’s symptoms, delirium severity and nurses’ general psychological distress and burnout. The study also opens the delirium experience research in nurses to a less explored population. In contrast, most prior studies on nurses’ distress were done in palliative or psychiatric-care settings, and this one take place in an intensive care medicine department.

However, the study also has some limitations. This study was only carried out in two ICMD of the same hospital and the sample available was small, which makes it difficult to generalize our results and conclusions and allowed us to have limited power to test hypothesis and associations. The least common delirium symptoms might also have had a disproportional representation in this study which could affect the statistical analyses.

Future studies are needed to assemble a bigger sample to have more sensitive associations between symptoms, behaviours, nurses’ psychological characteristics and their distress. Research on distinct factors that could potentially influence distress levels in nurses are also interesting for future investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank for funding provided by the Foundation for Science and Technology (grant number SFRH/BPD/103306/2014), ERDF through the operation POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007746 funded by COMPETE2020, by National Funds through FCT within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (Ref. UID/IC/4255/2013) - Project: “Impact of delirium on the elderly, their family and health professionals” Research team: Sónia Martins, Raquel Correia, Elika Pinho, Cristiana Paulo, Maria João Silva, Ana Teixeira, Liliana Fontes, Luís Lopes, Luís Azevedo, José Artur Paiva, Lia Fernandes. The authors wish also to thank the clinical staff, patients and their families for their collaboration.

Authors Biography

Inês Baptista

Medical student in Faculty of Medicine of University of Porto

Sónia Martins, MSc, PhD

Clinical Psychologist and Researcher at Center for Health Technology and Services Research - CINTESIS@RISE, Faculty of Medicine, University Porto (FMUP), Porto, Portugal.

Ana Teixeira, RN, PhD

Adjunct Professor at Instituto Politécnico de Saúde do Norte, IPSN-CESPU, Escola Superior de Enfermagem do Tâmega e Sousa; Researcher at Center for Health Technology and Services Research - CINTESIS@RISE and at Innovation in Health and Well-Being Research Unit (iHealth4Well-being), IPSN-VS, CESPU.

Liliana Fontes, RN

Nurse at Intensive Care Medicine Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João (CHUSJ), Porto, Portugal.

José Artur Paiva, MD, PhD

Director of Intensive Care Medicine Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João (CHUSJ). Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine - University Porto (FMUP), Porto, Portugal.

Lia Fernandes, MD, PhD

Full Professor and Director of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health Department of Faculty of Medicine - University of Porto (FMUP). Psychiatrist Senior Graduate Assistant in the Psychiatry Service, Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João (CHUSJ), Porto, Portugal.