Introduction

To make emotions measurable and understand their universality and variation, Ekman (1972) developed a universal program of facial expressions of affect, proposing the existence of "prototypical facial expressions" and their correspondence to basic emotions. This would be a process independent of the presence of a receiver and its interpretation independent of context. However, several authors have demonstrated the role of context in recognizing emotional facial expressions (Carrol & Russell, 1996; Fernandez-Dols & Carrol, 1997; Aviezer et al., 2008; Calbi et al., 2017). In contact with others, humans express their affectivity and emotional states through verbal and nonverbal channels of communication. In clinical and health contexts, patients express their emotional states in the same way, and the role of the healthcare professional is fundamental for the interpretation and contextualization of their emotional states. Emotional expressions indeed have the potential to provide information about the health of the individual expressing them (Hareli et al., 2020). Thus, identifying the patient's emotional state is a necessary skill for the healthcare professional to increase the effectiveness of personal interaction, as facial expressions are one of the most important parts of nonverbal communication and an excellent guide to understanding a "true" emotional state even when the person tries to hide it (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2021). Considering the healthcare professional's connection to the patient's emotional expressiveness (Versluijs et al., 2021), and the context of information accompanying healthcare delivery, the emotional recognition of user facial expressions may be influenced by the clinical history accompanying them. Taking into account emotional information in the clinical and healthcare context, the research framework of this study was centered on three themes: the importance of understanding emotional expressiveness in clinical and healthcare practice, facial expressions of emotions, and the importance of context in decoding them. Thus, the objective of our study is to verify whether and how the clinical history and the associated clinical condition (e.g. depression) influence clinical psychologists’ interpretation of facial expressions especially in cases of mixed emotional signals.

State of the Art

Emotions and Facial Expression

The face has been considered an important source of information for deciphering and recognizing emotional expressions. With the purpose of making emotions measurable and understanding their universality and variation across cultures, Ekman (1972) developed the neurocultural theory. According to this theory, there are brain mechanisms that are triggered by specific situations, such as a universal program of affective facial expressions, common to all people of all cultures, associating the emotions each individual feels with the facial expressions demonstrated. On the other hand, the theory postulates that everyone expresses emotions in the same way in non-social environments and that in social situations conscious techniques of emotional expression management are used, or display rules that override the universal program. This perspective, called the Emotional Expression Approach (de Sousa, 2010), has been privileged in studies of emotional expression recognition in clinical contexts. In part, due to the central role of emotions in the therapeutic process, and on the other hand, because the use of prototypical patterns of emotions allows for the recreation of emotional stimuli more easily in judgment studies. Thus, being a decoding study, our research will start from the prototypical expressions of some basic emotions in the clinical contexts (anger, fear and sadness) but we will also take into account mixed emotional expressions of these and the role of context (clinical history).

Mixed Emotional Signals

The use of schematic faces or static facial expressions at maximum intensity has been pointed out as a limitation in research on emotions and their facial expressions (LeMoult et al., 2009). In real life, individuals process a wide variety of emotional stimuli with signals of lower intensity than prototypical facial expressions, as well as mixed emotional signals (Krumhuber et al., 2013). Rarely do expressions occur at their maximum intensity or only in their prototypical configuration (Scrimin et al., 2009). Therefore, procedures for morphing prototypical emotional expressions have been used to obtain ambiguous facial expressions with different degrees of each emotion, similar to the expressiveness observed in everyday life, which can offer a powerful training opportunity for clinicians (Versluijs et al., 2021). Thus, aiming to approximate the stimuli to those found in a real-life situation, this study will use prototypical emotional expressions of medium intensity that will undergo a morphing procedure, resulting in expressions with mixed emotional signals. These will be used in conjunction with the prototypical expressions, to have facial expressions more similar to the expressiveness of everyday life and clinical settings. To be able to recognize mixed emotional signals in therapeutic context is important to clinical psychologists, in order to adapt interventions and maximize empathy.

Clinical History as Context

According to Fernández-Dols and Carroll (1997), proponents of the Emotional Expression Approach assume that the influence of context on emotion recognition is analogous to the influence of the face. However, studies by Fernández-Dols et al. (1993) reveal differences between these influences, suggesting that it depends on the type of context used. For example, texts describing less common situations required less time to be categorized in terms of emotions, and considering that facial categorization is rapid, training to categorize this type of situation would increase the influence of context. By selecting unusual social contexts, although highly prototypical, the influence of context on the judgment of non-matching combinations was shown to be identical to the influence of facial information. Taking this into account, the context in our study will be represented by data of clinical history, which can be associated to clinical condition, such as major depressive disorder, signs and symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder, and panic disorder. For the neutral context, a text was constructed following the same format but without any signs or symptoms of disorder.

Method

Participants

The participants were professionals with training in clinical psychology, residing within the national territory, engaged in clinical practice or not. Convenience and snowball sampling were used, and the only inclusion criterion was to be a clinical psychologist. A total of 119 responses were collected, of which 53 were incomplete and 6 were excluded. The final sample comprised 60 participants, aged between 24 and 58 years (M= 36; SD= 9.2), with 6 (10%) male and 54 (90%) female participants. The majority were single (46.7%), and years of practice ranged from zero to 27 (M= 9; SD= 7.1), with 42 subjects (70%) currently engaged in clinical practice. In terms of theoretical orientation, the majority (51.7%) selected Cognitive and Behavioural. The options Integrative and Eclectic, Systemic or Family, and Psychoanalytic or Psychodynamic have an equal representation. Of the total sample, 49 participants selected only one theoretical orientation (82%), seven selected two (13%), and one selected three (2%).

Instruments

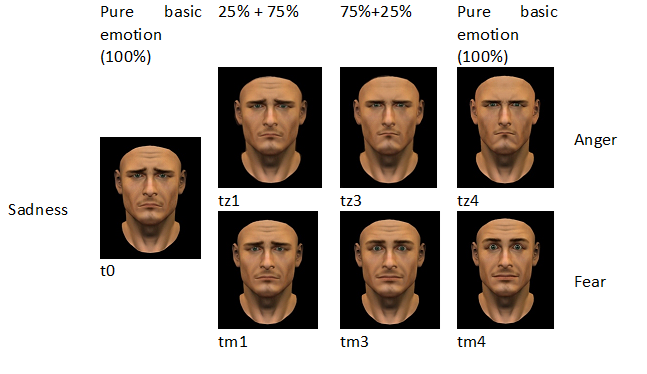

A preliminary exploratory study was conducted with the aim of validating the representativeness of clinical histories, assessing the emotions associated with them, and validating the representativeness of prototypical images of the 3 chosen basic emotions. The stimuli considered (images and texts) were presented to a group consisting of four clinical professionals with different theoretical formations in psychology, with recognized practical experience in clinical psychology and who were not part of the sample. This study resulted in: 1) the adjustment of the intensity of the facial expression in the prototypical image of anger, which in its initial version could be associated with a state of attention/concentration of the individual; 2) the adaptation of the clinical history text, representing major depressive disorder, which in its initial version presented insomnia instead of excessive daily tiredness, a symptom considered less common in the clinical practice of the participants. In the next phase, in a within-subjects design, a questionnaire was constructed consisting of: 1) a group of sociodemographic questions (age, gender, marital status, theoretical orientation, clinical practice; years of professional practice); 2) Seven groups of judgment requests pairing images (7) and contexts (3), totaling 21 combinations (grouping 3 images per context). Images: Realistic synthetic images modeled using Poser 8 with the VirtualFACS©2.0 computer tool were utilized. The faces belonged to a male model, exhibiting prototypical expressions of sadness, fear, and anger. To approximate the expressions to those observed in everyday life, prototypical expressions with medium intensity were used, and from these, a set of images with mixed emotional signals was created. The construction of these images was carried out through a morphing of prototypical expressions of two different emotions using WinMorph 3.01 software. Based on the study by Scrimin et al. (2009), a two-dimensional image transformation system was used to generate ambiguous images with different degrees of each emotion on a continuous line between two points: Sadness-Fear; or Sadness-Anger. For each continuous line, pertinent anatomical areas such as the mouth, eyes, and nose were used as control points. Images corresponding to 25%, 50%, and 75% of each continuous line, ranging from one emotional pole to the other (from 0 to 100%), were then generated. Images corresponding to 50% were discarded, resulting in 7 images with differences among them (see Figure 1). As depicted in Figure 1, the resulting set of images consists of images with prototypical emotional expressions (t0, tz4, and tm4) and images with a mixed emotional expression composed of a dominant emotion (present at a level of 75%) and a non-dominant emotion (present at a level of 25%).

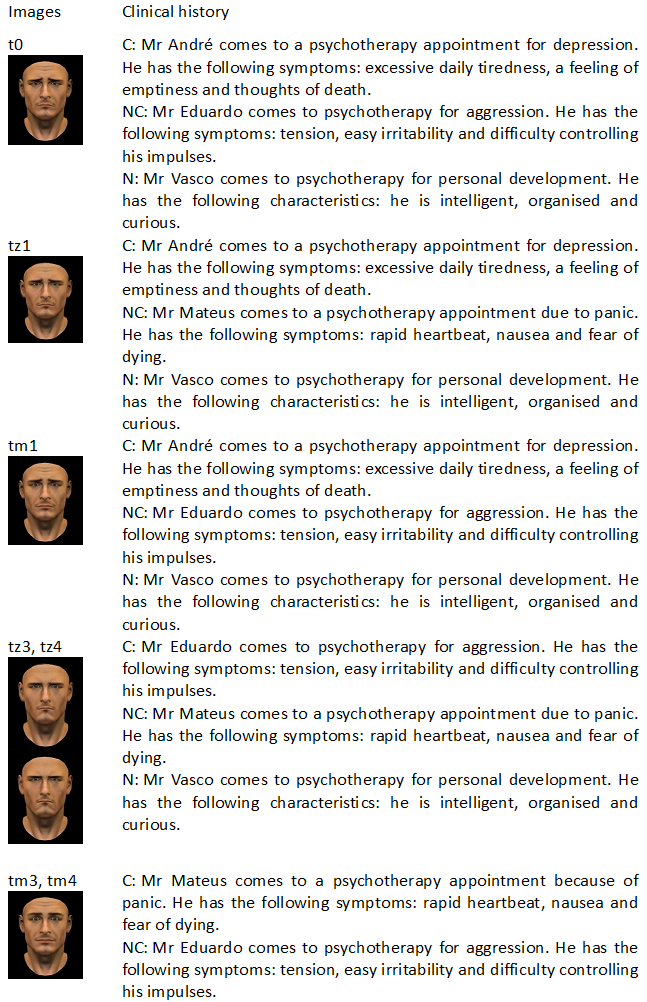

Clinical histories as Contexts: Brief clinical histories were constructed (see Table 1), standardized based on the signs and symptoms outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) for the disorders we deemed most easily associated with the 3 basic emotions used in the study, whose representativeness was validated in the exploratory study. Signs and symptoms of intermittent explosive disorder, panic disorder, and major depressive disorder were selected. For the neutral context, a text was constructed following the same format but without any signs or symptoms of disorder. According to validation study of images, texts and emotions: sadness was associated to major depressive disorder; anger was associated to intermittent explosive disorder and fear was associated to panic disorder. A story was considered concordant when the implicit emotion matched the dominant basic emotion in the image (75% or 100%): t0, tz1, tm1 for sadness; tz3, tz4 for anger; tm3, tm4 for fear.

and a story was considered non-concordant when the implicit emotion was not present at all in the image. Different combinations were made according to Table 1.

Table 1 Identification of contexts for each image.

Note. C = Concordant; N = Neutral; NC = Non-concordant

Judgment: For each image associated with the presented context, participants were asked to assign the 3 basic emotions (anger, fear, and sadness), always in this order, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 corresponds to "None" and 5 to "Very"). The questionnaire was constructed using the LimeSurvey platform and according to the manual procedure, the order of presentation of the clinical histories and the order of the questions associated with them in each questionnaire presentation were randomized.

Procedure

The questionnaire was made available through an online hyperlink, and participants were requested to collaborate. Each participant was presented with 21 combinations (7 images x 3 clinical contexts) and a total of 31 questions. All incomplete responses were excluded, and the data were analyzed using SPSS version 28 software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that the data distribution does not approximate normality, so non-parametric analysis techniques were chosen. The invitation to collaborate indicated the purpose of the study and description, the researcher team and contacts, the requirement for participation (to be a clinical psychologist), information on the duration of the questionnaire (3 to 5 minutes). It was made clear that participation was anonymous, with no risks associated to the participant and the data was confidential and would only be used for scientific purposes. Participation was voluntary and they were free to withdraw at any time. By following the link in the invitation, potential participants would then see on the homepage of the questionnaire the essential information contained in the email or media publication requesting collaboration and a question to decide whether or not to take part in the study. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. They were also asked to forward the protocol to professional colleagues if possible.

Results

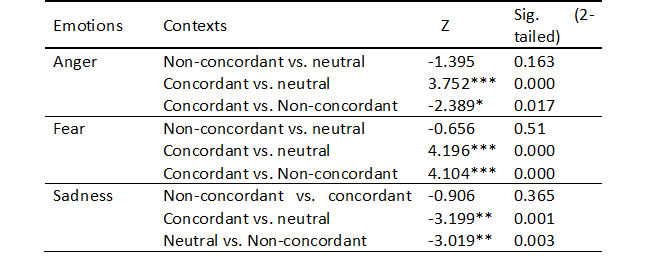

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the distribution of the dependent variables was not normal. To identify any intra-group differences in the recognition of facial expressions of emotion in the three conditions (concordant history, non-concordant history, neutral history), the Friedman test for repeated measures was conducted. The analysis of variance of the results of the variables regarding images with the same dominant emotion in different contexts indicates that there are significant differences in the recognition of anger (χ²= 15.8, p < 0.001), fear (χ²= 22.8, p< 0.001), and sadness (χ²= 10.1, p= 0.006) depending on the history accompanying the image. A post-hoc analysis using the Wilcoxon test and applying a Bonferroni correction resulted in a significance level set at p < 0.017 (p< 0.05 / 3 conditions) and the following results (see Table 2): a) There are no significant differences in the recognition of anger between the non-concordant and neutral conditions (Z= -1.395, p= 0.163). However, there is a statistically significant increase in the recognition of anger in the concordant condition vs. the neutral condition (Z= -3.752, p< 0.001) and vs. the non-concordant condition (Z= -2.389, p= 0.017). The median levels of anger recognition in the concordant, non-concordant, and neutral conditions were also 8 (7 to 9, 7 to 9, and 6 to 8, respectively); b) There are no significant differences in the recognition of fear between the non-concordant and neutral conditions (Z= -0.656, p= 0.51). However, there is a statistically significant increase in the recognition of fear in the concordant condition vs. the neutral condition (Z= -4.196, p< 0.001) and vs. the non-concordant condition (Z= -4.104, p< 0.001). The median levels of fear recognition in the concordant, non-concordant, and neutral conditions were 8 (6 to 9), 7 (4 to 9), and 7 (4 to 8), respectively; c) There are no significant differences in the recognition of sadness between the non-concordant and concordant conditions (Z= -0.906, p= 0.365). However, there is a statistically significant increase in the recognition of sadness in the concordant condition vs. the neutral condition (Z= -3.199, p= 0.001) and in the neutral condition vs. the non-concordant condition (Z= -3.019, p= 0.003). The median levels of sadness recognition in the concordant, non-concordant, and neutral conditions were 13 (12 to 15), 13 (11 to 15), and 12 (10 to 14), respectively.

Table 2 Results of the comparison of means for the attribution of the dominant emotion between pairs of conditions

* p< .05 ; ** p< .01; *** p< .001

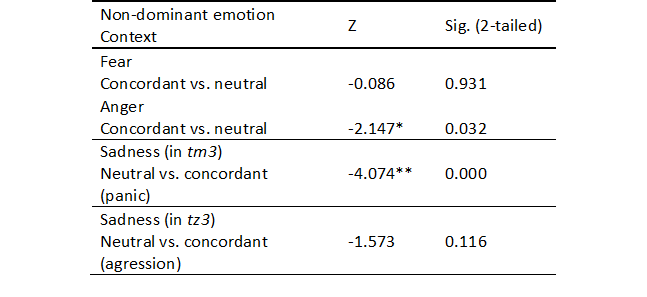

To check if the clinical history had any influence on the judgment of mixed signals, the Wilcoxon test, as a non-parametric alternative to the Student's t-test, was performed to test differences in the judgment of the dependent variable (facial expression of emotion) in relation to the independent variable (clinical history). The comparison was made between two related samples: the level of recognition of the non-dominant emotion in the presence of the concordant history (with the dominant emotion) and the same in the presence of the neutral history. There were no significant differences: a) in the recognition of sadness present in the facial expression (25%) between the story concordant with the dominant emotion (anger) and the neutral story (Z= -1.573, p = 0.116); b) in the recognition of fear (25%) between the story concordant with the dominant emotion (sadness) and the neutral story (Z= -0.086, p= 0.931) (see Table 3).

However, we also found that: a) there is a statistically significant increase in the recognition of anger as a non-dominant emotion in the facial expression when in the presence of the neutral story vs. the concordant story with the dominant emotion (sadness; Z= -2.147, p= 0.032). The median level of recognition of anger in the concordant and neutral conditions was also 1 (1 to 2); b) there is a statistically significant increase in the recognition of sadness as a non-dominant emotion in the facial expression when in the presence of the concordant story with the dominant emotion (fear) vs. the neutral story (Z= -4.074, p< 0.001). The median levels of recognition of sadness in the concordant and neutral conditions were 2 (1 to 3) and 1 (1 to 2), respectively (see Table 3).

Table 3 Results of the comparison of means for the attribution of the non-dominant emotion between pairs of conditions

tz3 = sadness 25% - anger 75%; tm3 = sadness 25% - fear 75%. * p < .05 ; ** p < .001

To verify the influence of clinical history on the therapist's judgment regarding the attribution of emotions not present in the presented image, an analysis of variance for related samples was carried out using the Friedman test. The levels of attribution of an emotion not present in the facial expression in different contexts were compared. It was found that there were no significant differences: a) in the attribution of anger to the image referring to the sadness-fear mixture (75%-25%) between different contexts (χ²= 5.5, p= 0.06); b) in the attribution of anger to the image referring to sadness (100%) between different contexts (χ²= 0.43, p= 0.81); c) in the attribution of sadness to the image referring to anger (100%) between different contexts (χ²= 1.26, p= 0.53). However, significant differences were observed: a) in the attribution of fear to the image referring to sadness-anger mixtures (25%-75%, 0-100%) between different contexts (χ²= 86.8, p < 0.001); b) in the attribution of fear to the image referring to the sadness-anger mixture (75%-25%) between different contexts (χ²= 6.1, p= 0.048); c) in the attribution of fear to the image referring to sadness (100%) between different contexts (χ²= 7.22, p= 0.027); d) in the attribution of anger to the sadness-fear mixtures (25%-75%, 0-100%) between different contexts (χ²= 13.0, p= 0.002); e) in the attribution of sadness to the image referring to fear (100%) between different contexts (χ²= 11.68, p= 0.003). A post-hoc analysis to understand the differences, using the Wilcoxon test and applying a Bonferroni correction, resulted in a significance level set at p< 0.017.

This analysis reveals the following significant results: a) There are significant differences in the attribution of fear to an image in which it is not present and whose dominant emotion is anger, between the contexts of aggression and panic (Z= -6.508, p< 0.001), as well as aggression and neutral (Z= -6.443, p< 0.001); b) There is a statistically significant increase in the attribution of anger to an image in which it is not present and whose dominant emotion is fear, when associated with an aggressive context vs. a neutral context (Z= -2.960, p= 0.003); c) There are significant differences in the attribution of sadness to an image of fear between the neutral and panic contexts (Z= -2.624, p= 0.009), as well as neutral and aggression (Z= -2.863, p= 0.004);

Discussion

There was a statistically significant increase in the recognition of facial expressions of anger and fear in the presence of a clinical history concordant with the emotion compared to other contexts. There was an increase in emotion recognition in the presence of the concordant clinical history compared to the neutral history, but also in the presence of the neutral history compared to the non-concordant history. We found that the recognition of sadness in the presence of either the concordant or non-concordant history is identical, probably due to the similarity effect proposed by Aviezer et al. (2008). For this comparison, one of the variables used in the non-concordant context was the association of image tz1 (75% sadness + 25% anger) with the clinical history of panic, whose most frequently associated emotion is fear. Our results align with other studies, suggesting that emotions are more easily recognized in the presence of a concordant context than a non-concordant or neutral one, and that the greater the similarity between the facial expression of the presented image and the face prototypically associated with the context, the greater the influence of the context (Aviezer et al., 2011). According to Aviezer et al. (2011), sadness and fear share similarities. In a study indicated by the authors, the prototypical facial expression of sadness presented in isolation was recognized as sadness by 74% of the participants, but when associated with a context of fear, it was recognized as such by only 20%.

In our study, there was also a higher recognition of sadness as the non-dominant emotion when in the presence of the concordant history with fear than with the neutral history. It is believed that the influence of this context is due to the similarity effect between the facial expression of sadness and the facial expression of fear.

In the analysis of the influence of clinical history on the recognition of mixed emotional signs, there was greater recognition of the signs of anger in the facial expression, as a non-dominant emotion, when in the presence of the neutral story than of the story in agreement with the dominant emotion (sadness). This result could suggest an influence of the clinical context (neutral story), on the recognition of anger in mixed signals. Or, on the other hand, it can show the overvaluation of emotional signs of anger in a neutral context, an effect that should be more explored by other studies. There was also greater recognition of sadness, as a non-dominant emotion, in the presence of a story in agreement with fear than in the presence of a neutral story. The influence of this context is thought to be due to the same similarity effect, more specifically a greater similarity between the facial expression of sadness and the facial expression of fear.

In the analysis of the influence of clinical history on the therapist's judgment regarding the attribution of emotions not present in the presented image, there was a statistically significant increase in the attribution of anger to images where it is not present and the dominant emotion is fear when associated with an aggression context vs. a neutral context. This result could suggest an influence of the clinical history context (aggression context), on the attribution of anger. It was also found a greater attribution of sadness to the fear image associated with the panic context, which suggests the similarity effect and therefore the contextual effect. However, this increase in the attribution of sadness compared to the neutral condition also occurs in the presence of the aggression context. Therefore, these results highlight the effect of the overvaluation or undervaluation of a facial expression of emotion determined by clinical histories as contexts. Following the objective of our study, our results indicate that clinical histories and the associated clinical condition influences clinical psychologists’ interpretation of facial expressions, emphasizing that emotions are more easily recognized in the presence of a concordant clinical history as context than a non-concordant or neutral one. The influence of clinical history as context is greater when the similarity between the facial expression presented and the face prototypically associated with the context is higher. Clinical histories as contexts also influence the recognition of mixed emotional signs (anger and sadness). Clinical histories also influence therapist's judgment regarding the attribution of emotions not present in the presented image (anger and sadness). These effects of the overvaluation or undervaluation of a facial expression of emotion determined by clinical histories as contexts evolve prototypical images of an emotion and also images with mixed emotional signals. In future studies, it would be useful to conduct detailed research about these effects.

Our study had some limitations: the use of a limited number of basic emotions and specific clinical contexts (anger, fear, sadness), which restricts the generalizability of results to other emotions or contexts; Lack of experimental control over the influence of familiarity with specific clinical contexts, as some participants may have more experience with certain types of patients; Variation in clinical practice levels among participants, which may have introduced bias, as less experienced psychologists could interpret expressions differently from those with more experience.

Therefore, facial recognition is a central element in social interaction processes and understanding the processing of facial expressions is significant for helping emotional regulation and promoting the therapeutic relationship (Krause et al., 2021). This is particularly crucial when the clinical context experienced by the individual involves emotional and communication disturbances that cause disruptions in social functioning due to problems in producing emotional facial expressions and emotional speech (such as dysarthria) and difficulties in recognizing verbal and nonverbal emotional cues from others (Prenger et al., 2020), where the interpretation of facial emotions undoubtedly impacts therapeutic communication and interprofessional communication in the context of healthcare (Bani et al., 2021).

Conclusion

We found evidence that the clinical context determines the overvaluation or undervaluation of a facial expression of emotion and that the presence of mixed signals accentuates this contextual effect when it comes to sadness, fear, and anger. However, further research will be needed to verify if these results are transferable to the judgment of other emotions.

Implications in clinical practice

Our study reveals some effects that clinical histories emphasize, and these could be important to the training of clinical practice of psychologists and other clinical professionals. To be able to recognize mixed emotional signals in therapeutic contexts and be conscious of these effects is important to psychologists and healthcare professionals, such as nurses, in order to identify problems, adapt interventions and maximize empathy. Therefore, the development of training that considers not only prototypical facial expressions, but also context variations and mixed emotions and expressions, will lead to development of skills applicable in clinical practice. Thus, the identification and correct interpretation of facial expressions of emotions, considering their contextual situation, play an important role in professional interaction, helping formulate and regulate clinician behavior in response to the emotions expressed by the patient, including mixed emotions. The ability to identify and interpret emotions through people's facial expressions can help establish a relationship of trust and therapeutic communication. There is increasing evidence that clinicians' awareness and ability to respond to their own and others' emotions influence their ability to provide safe and compassionate healthcare, a particularly pertinent issue in healthcare overall.