Introduction

The working conditions of judicial professionals have been approached typically by the Sociology of Law and Health Psychology, mainly through a quantitative methodological approach (Casaleiro et al., 2021). This article addresses the challenges of adopting a mixed-methods approach in empirical research on the working conditions of court clerks, judges and public prosecutors in Portuguese courts, discussing the experience of the project “QUALIS”.

Judicial professionals are not traditionally regarded as workers, neither by the Sociology of Work, Organisations and Professions, which does not study them, nor by the Sociology of Law, that, until recent decades, has had as its main focus, the procedural, institutional and organisational dimensions of law and, within legal professions, lawyers (Casaleiro et al., 2021; Dias et al., 2021)1. Magistrates2 tend to be regarded as representatives of the State, who occupy a privileged position when compared to most employees in the labour market (Blackham, 2019), whether in the public or private sector.

The first studies on judicial professionals’ working conditions emerged in the 1980s and 1990s and came from the Socio-Legal (Ryan et al., 1980), Psychology and Psychiatry fields (Eells & Showalter, 1994), co-authored by professionals from the judiciary itself (e.g.Rogers et al., 1991). After this pioneering work and as new models of judicial management and judicial reforms were implemented, in the last decade, studies on judicial professions focusing on working conditions re-emerged slowly in the fields of Sociology and Psychology (Casaleiro et al, 2021). As the “new public management” paradigm emerged, magistrates have progressively been regarded not only as independent decision-makers, but also as actors providing a service in a public body (Blackman, 2019) and courts also began to be seen as working spaces (Branco, 2013). In this relatively new area of research, that focuses on the working conditions of judicial professionals, discussing the methodological approach of a specific research project, such as “QUALIS”, may benefit future national and international studies.

The article focuses on the challenges in selecting and building the data collection methods and in analysing results in the research project “QUALIS” on the working conditions of judges, public prosecutors and court clerks. The research project adopted a mixed-methods design and technique, resorting to the application of an online questionnaire survey and case study interviews. The questionnaire and interviews were used to gather information about judicial professionals’ perceptions of working conditions in courts (e.g. physical environment, work intensity and social environment), as well as of the work-family conflict, and the impact on their health and well-being.

We start by discussing the state of the art in the study of the working conditions within the judicial professions. Then we present the settings of the research project, discussing two methodological challenges: selecting and building the data collection methods and analysing the mixed-methods data results.

State of the art: a recent approach to working conditions in courts

The concept of working conditions has progressively evolved from a restricted definition associated with physical integrity to a focus on the conception of well-being, culminating in an understanding of working conditions associated with quality of work and employment. Recent studies of Sociology of Work and Eurofound adopted a comprehensive definition of working conditions, related to issues such as health and safety in the workplace, work organisation, quality of working life and work-life balance (Cabrita & Peycheva, 2014; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions [Eurofound], 2021; Lima, 2012). In this sense, literature has highlighted the connection between individual and organisational wellness (Jack & Brewis, 2005), and the impact of organisational culture and climate on stress and/or emotions (Cooper & Cartwright, 2001; Tsai & Chan, 2010).

Studies on the working conditions within judicial professions are scarce and relatively new in most countries (Casaleiro et al., 2021), although, since 2000, there has been an increased interest in this theme. This recent evolution reflects the need to explore the multidimensionality of working conditions and its impact, although not in an integrated way. There are, as mentioned above, two main kinds of studies on working conditions focusing on judicial professions (Casaleiro et al., 2021): Psychology and Psychiatry research studies centred on the psychosocial risks and professional stress and burnout (e.g.Moniz et al., 2022, 2023; Tsai & Chan, 2010); and studies in the field of Sociology of Law concerning questions such as job satisfaction and work organisation (e.g.Mack et al., 2012; Roach Anleu & Mack, 2014). Another kind of contribution can be added coming from judicial professionals themselves, as shown by a recently published book with several reflections from Portuguese judges or public prosecutors, among others, on several topics, including working conditions in courts (Coelho et al., 2023).

Despite the discipline and geographical dispersion, studies unanimously show a general dissatisfaction with working conditions, particularly in terms of the intensity of work (Casaleiro et al., 2021). Judges and public prosecutors perceive their workload as increasingly demanding, characterised time constraints, heavy caseloads, backlogs, and complex cases (Ferreira et al., 2014; Na et al., 2018). This perception may be exacerbated by “the highly demanding nature of management initiatives and court performance evaluation programmes, setting productivity standards for judicial professionals and courts” (Casaleiro et al., 2021, p. 23). Furthermore, “the studies highlighted the importance of aspects of the judicial work itself, as primary sources of occupational stress among judicial professionals” (Casaleiro et al., 2021, p. 23). Among the specific sources of stress for judges and public prosecutors are judgements and decision-making, exercising judicial discretion, heavy caseloads, time constraints, complex legal issues, rapidly changing laws, and emotionally demanding cases, especially those involving children, violence, and sexual offenses (Casaleiro et al., 2021; Flores et al., 2009; Rogers et al., 1991). The burden of making life-altering decisions, coupled with perceived insufficient social support (Na et al., 2018; Tsai & Chan, 2018) and deficient preparation and training for their duties (Mack & Roach Anleu, 2008; Na et al., 2018; Thomas, 2017), may contribute to the stress experienced by judges and prosecutors (Casaleiro et al., 2021).

While the previous results may suggest otherwise, judicial professionals express a high level of job satisfaction, according to multiple studies (Roach Anleu & Mack, 2014). Judicial professionals face significant workloads and occupational stress, which increase their risk of burnout. However, they also enjoy high levels of job control and rewards. In sum, judicial professionals, such as judges or public prosecutors, who combine demanding roles with substantial autonomy, report high levels of job satisfaction (Hagen & Bogaerts, 2014). In essence, judicial professions are characterized by a combination of high job demands and high job satisfaction (Casaleiro et al., 2021).

Recent empirical studies reached similar conclusions and, while adopting mostly a quantitative methodology3 there is no consensus on the instruments used. Most of the psychological studies used one or more pre-existent measurement scales. For example, Tsai and Chan (2010) administered the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), Siegrist’s Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERI), and Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). “Another common approach to individual perceptions of working conditions was the creation of questions that were specifically designed for each study purpose” (Casaleiro et al., 2021, p. 19). Ciocoiu et al. (2010) developed a questionnaire identifying 77 potential stressors for magistrates, categorized into five areas: physical-chemical environmental factors; current work-related factors; factors related to the magistrate’s role in the profession; features related to the organisational structure and the professional climate; and individual factors related to the interaction between the professional and socio-family environments. The United Kingdom Judicial Attitudes Survey (Thomas, 2017) also explored various aspects of working conditions, including workload, remuneration, and professional development opportunities. “In addition, some studies included clinical measures to assess health and well-being in the workplace, targeting occupational stress, burnout and secondary traumatic stress” (Casaleiro et al., 2021, p.19). For example, Flores et al. (2009) adopted a comprehensive approach, using both self-report measures of stress and clinical measures like the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale and a short form of the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnostic. Schrever et al. (2019) conducted a study in Australia, using standardized psychometric instruments to measure judicial stress and well-being. This research allows for comparisons with the general population.

The settings of a mixed-methods research project: the case of “QUALIS”

The Portuguese legal system is divided into two main jurisdictions: ordinary courts for criminal and civil matters, and administrative and tax courts. Both jurisdictions have a three-tier structure: the higher-ranking and nationwide competent Supreme Court of Justice and Supreme Administrative Court; the appeal courts (Tribunais da Relação or Tribunais Centrais Administrativos - second instance courts); and the hierarchically lower and territorially narrower district courts (Tribunais de Comarca or Tribunais Administrativos e Fiscais - first instance courts).

The research project focused on the working conditions of three different judicial professionals, who work daily in all Portuguese courts, regardless of the jurisdiction or instance: judges, public prosecutors and court clerks.

Portuguese judges are responsible for administering justice on behalf of the people. To preserve independence and impartiality, they are prohibited from any public or private role except for unpaid academic or research activities in law. Public prosecutors, in Portugal, assume different functions, such as representation of the State and defence of the democratic lawfulness, but also conduct criminal investigations and proceedings, protect the rights and interests of children and young people and defend collective and diffuse interests, among others. Both judges and prosecutors undergo a three-stage selection process to access the profession, involving a public tender (consisting of knowledge tests, a curriculum evaluation, and a psychological selection test), attendance of a theoretical and practical course at the Centre for Judicial Studies (Centro de Estudos Judiciários); and, finally, a training period at courts. Court clerks provide essential procedural assistance within both the courts or public prosecution services in Portugal. To begin a career as a court clerk, individuals must start as either an auxiliary clerk (escrivão auxiliar) in the judiciary or an auxiliary legal clerk (técnico de justiça auxiliar) in the public prosecution service. These entry-level positions require a professional training programme and successful completion of the all selection process.

A previous survey carried out by some members of the “QUALIS” team, in 2014, showed that 72.9% of judges and public prosecutors considered their workload to be excessive, 75.5% felt professional stress in their work, and 81.1% claimed that work-associated stress impacted their personal/family life (Ferreira et al., 2014)4 It provided data supporting the possible deterioration of working conditions in the courts and occupational health risks for judicial professionals, highlighting the need for further research. And this theme became more relevant as a wide range of reforms took place in Portugal in 2013. The main reform referred to the judicial organisation, implemented during the Troika5 period, that reduced 232 lower courts to 23 district courts (concentration process), each with jurisdiction over a wider territorial base and a higher level of specialization (Dias & Gomes, 2018). To preserve accessibility for citizens, “most of the smaller courts were transformed into local sections or branches of the now streamlined judicial system” (Dias & Gomes, 2018, p. 174).

Furthermore, since this reform took place, “the management of each court of first instance is carried out by a management board (Conselho de Gestão). The board has a tripartite structure composed of a presiding judge, a coordinating public prosecutor and a judicial administrator” (Dias et al., 2021, p. 4). This tripartite structure sought to streamline distribution and procedural requirements, simplify human resources allocation and provide more autonomy to court management (Dias et al., 2021; Dias & Gomes, 2018).

Considering the judicial reforms and the conclusions of the previous research, it was important to understand the impact of the legal changes on the judicial working conditions of judges, public prosecutors and court clerks. As mentioned, “QUALIS” adopted a “comprehensive definition of working conditions, considering not only physical working conditions but also the management and work organisation models and the working environment and health and well-being impacts on judicial workers” (Dias et al., 2024, p. 249). More concretely, based on the literature review, “QUALIS” focused on exploring the different dimensions of working conditions, which include courts’ physical environment, work intensity and social environment, and individual impacts such as work-family conflict and health and well-being impacts. This double concern with the organisational aspects of working conditions and their impact on individuals required a synergy of perspectives, which was achieved by bringing together researchers from the areas of Law, Sociology and Health Psychology. The research team was, therefore, composed of researchers from the Permanent Observatory of Justice (OPJ), of the Centre for Social Studies (CES) of the University of Coimbra, from different disciplinary backgrounds. The research team also opted for a mixed-methods approach, identifying and quantifying the characteristics of working conditions and their impact, making use of a questionnaire to collect data in a survey design. And, simultaneously, studying the working conditions in a broader context with a qualitative approach, with two case studies and using interviews to consult participants. This project benefited from two decades of research experience in OPJ, with multiple studies on different topics about the Portuguese judicial system (Dias et al., 2023). Although this project focused on a new theme, the knowledge of the research field was an added value to its development.

Challenges in selecting and building the data collection methods: specificities of the judicial system

The first instrument to be applied was a questionnaire. The research team agreed on the advantages of designing closed questions for participants’ self-completion and providing the questionnaire online6. The link for the questionnaire survey was emailed to all professionals working in courts (n=10,978 on December 31st, 2020), between October and November 2020, by the governing and management bodies of the judiciary (high councils). Additionally, other relevant entities of the justice system (professional associations and unions) appealed for participation in the study (via email and by their online platforms). These efforts generated a response rate of 15.8 per cent (n= 1,739 respondents)7.

To capture and enrich the information obtained through the questionnaire survey and to further the understanding of working conditions’ broader context factors and impacts, two case studies (Central Lisbon and Coimbra district courts) were designed and qualitative data was collected through semi-structured interviews. These two district courts were selected considering their geographical and caseload characteristics: the Lisbon district corresponds to a densely populated urban area, with great litigation complexity and a new judicial campus; the Coimbra district corresponds to a large district with urban and rural areas, with medium complexity litigation and dispersed judicial services.

The research adopted the snowball sampling technique, a nonprobability sampling technique, to recruit the interviewees. The interview script closely followed the questionnaire structure, aiming to capture any of the specificities of the judicial careers that the use of standardised instruments may preclude. A total of 73 interviews were conducted between April and July 2021 with judicial professionals, including judges, public prosecutors, and court clerks, working across 9 different court buildings in Central Lisbon and 20 court buildings in Coimbra district. In sum, 22 judges, 23 public prosecutors and 28 court clerks were interviewed, of whom 45 were women and 38 were men.

Initially, the research included an assessment of the working conditions under which the judicial professionals perform their duties in the courts, through direct observation of district courts, where information would be gathered about working conditions (physical conditions) and labour relations (socio-professional conditions) in an observational sheet. COVID-19 restrictions to travel and access to courts, and with the judicial professionals working mainly remotely, especially judges, led to the abandonment of this option. Between March 2020 and March 2021, there were several periods of lockdown in Portugal, with several restrictions on circulation across the country. Additionally, in response to the swift spread of the COVI-19 virus and the subsequent declaration of a state of emergency, access to Portuguese court buildings was limited, and in-person court services and proceedings were severely reduced8.

In settling this research design, it was the definition and construction of the questionnaire survey that raised more challenges in the process of integrating the contributions of the different disciplines. The legal review was exclusively conducted by the research members with a background in the Sociology of Law and Law. The planning of the online questionnaire survey included the literature review, the review of other measurement instruments (such as the European Working Conditions Survey Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire, OLBI, Work-Family Conflict Scale, surveys of judicial officers conducted in other places and/or for more limited purposes), and a pilot study to test the data collection instrument.

The pilot study included two methods: cognitive interviews and pilot testing (Geisen & Bergstrom, 2017). For the cognitive interviews, it was requested the collaboration of the professional associations to recruit two volunteers (one male and one female). The cognitive interviews were conducted in person with a small sample of respondents (a total of 6 professionals: two judges, two public prosecutors and two court clerks). After the respondents answered the questionnaire, a facilitator asked them to think aloud, describing their thought processes, emotional responses, and understanding of each question. The feedback of these professionals about the questionnaire’s content, comprehension, acceptability, difficulty, design, and length was very relevant. These interviews helped to determine if a question was ambiguous, confusing, or made people uncomfortable due to its content, which led to a revision of some of the answer options. Afterwards, the pilot testing survey involved formally testing the complete, structured questionnaire online with a small sample of respondents from designated members of the professional associations (one association for each profession).

The questionnaire addressed the following areas that reflected issues identified through the literature review and analysis of other materials, and concerns raised in the consultations: Sociographic and Professional information; Organisational working conditions, including physical environment, work intensity and social environment; and Individual impacts, including work-family conflict, burnout and health and well-being impacts. The questionnaire also included a topic related to COVID-19, considering the exceptional times of the pandemic, namely their working arrangements, work intensity and use of technologies during the COVID-19 crisis.

The elaboration of the questionnaire had two interconnected concerns: i) the questionnaire length; and ii) the specificities of judicial context and careers, which are intimately connected with the multidisciplinary approach and the need to balance the socio-legal and psychological approaches.

Firstly, considering that “QUALIS” used a comprehensive definition of working conditions and a multidisciplinary approach, one of the challenges was to avoid making an overly long questionnaire, as this could be off-putting for some potential respondents. Considering the disciplinary backgrounds and empirical traditions, the questions aimed to evaluate the impact on health and well-being came mainly from the psychology field, while the questions aimed to assess and characterise the organisational working conditions came from the sociological literature and were mainly adapted to the judicial specificities.

The final version of the questionnaire survey had 39 questions, distributed as follows:

12 questions on sociographic and professional characterizations. To examine the sociographic characteristics of the respondents, the participants answered about their judicial profession (judge, public prosecutor, or court clerk) and the corresponding professional category, sex, year and place of birth, household type and academic qualifications. To understand the professional characteristics of the respondents, it was asked where and in which court or Public Prosecution service they performed functions, if they had to commute to another court or Public Prosecution Service and if they held powers of presidency, direction, coordination and/or management. Magistrates were asked the year in which they started their career, excluding the mandatory course and training periods. Court clerks were asked in which year they started their career, excluding the probation period.

14 questions on organizational working conditions. To understand the organisational working conditions of the respondents, they were asked to evaluate the management and conservation/maintenance of their court building and working spaces, how often did work involved a high pace or working extra hours, what influenced the pace of work, and the relationship with the court management board.

13 questions on health and well-being impacts. To understand the impact on health and well-being, the choice rested mainly on clinical psychology contributions through the use of several scales: Work-Family Conflict Scale (WFCS) (Carlson et al., 2000; Vieira et al., 2014); World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Abbreviated version (WHOQoL-BREF) (The Whoqol Group, 1998; Vaz-Serra et al., 2006); the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Canavarro, 2007); Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) (Sinval et al., 2019); and Basic Scale on Insomnia symptoms and Quality of Sleep (BaSIQS) (Gomes et al., 2015; Miller-Mendes et al., 2019).

The research team sought to select instruments for measuring individual characteristics like health and well-being with established psychometric properties in the Portuguese population. This means using scales proven to accurately and consistently quantify their target concepts in individuals with specific characteristics. Furthermore, the research team attempted to integrate abbreviated versions of the scales in the questionnaire whenever possible, and scales that could independently measure different aspects of the concept, to accomplish the identified purposes and to avoid a long set of questions. For example, it used the short version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life9 (WOQoL-Bref) (The Whoqol Group, 1998; Vaz-Serra et al., 2006), out of which we only assessed the Physical Health10 and the Environment11 domains of quality of life. Furthermore, the organisational dimension was revised several times to avoid repetition or overlapping questions.

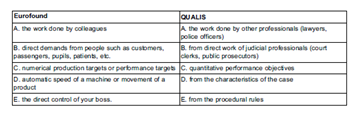

Secondly, all judicial professions have their specificities and problems related to their working conditions. The management and organisation of the judicial system differ from the organisational structures of many other private and public administrations. Judicial professionals must deal with difficulties in legal decision-making, with litigants and lawyers, procedural deadlines and cases involving severe social problems, among other issues. Thus, the organisational dimension was inspired by other surveys such as the Eurofound, but it was necessary to make several adaptations to reflect the judicial system’s reality. For example, to understand the pace of work determinants, the options for answering the question “What is your pace of work dependent on?” were adapted considering the legal review and pilot study of the survey (Figure 1). The last options mentioning the characteristics of the case and the procedural rules were added following the professionals’ suggestions in the cognitive interviews.

Figure 1 Original and modified response items for the question “What is your pace of work dependent on?”

Another example of adaptation is the use of “management bodies” (“órgãos de gestão”) instead of “boss” or “manager”. The model of governance of the Portuguese judicial system and management of the courts is dispersed over different entities, sometimes with competing and overlapping competencies (Dias & Gomes, 2018). Thus, most judicial professionals cannot identify a direct manager or boss. The different High Councils have responsibility in managing careers and disciplinary measures of each professional category - judges, public prosecutors and judges from the Administrative and Tax Courts -, except the Council of Court Clerks that has only disciplinary powers. Furthermore, the Supreme Court of Justice, the Supreme Administrative Court, the Appeal Courts (known as Tribunais da Relação) and the second instance administrative courts have administrative and financial autonomy.

The different High Councils (for Judges12 Administrative and Tax Courts13 and Public Prosecution14) are responsible for managing careers and disciplinary measures of each professional category (Dias et al., 2021). In what concerns court clerks, the Council of Court Clerks solely addresses disciplinary matters. It is the Directorate-General for the Administration of Justice (DGAJ)15 from the Ministry of Justice which is responsible for managing court clerks’ careers. Furthermore, and as already mentioned, since the reform of the judicial organisation in 2013, the management of each judicial court of first instance is carried out by a tripartite management board (Conselho de Gestão) (Dias & Gomes, 2018). Consequently, when asking for an evaluation of the work situation, “QUALIS” sentences (to which participants responded using a frequency rating scale) were like “The management bodies help and support you” instead of “Your manager helps and supports you” (Eurofound survey).

Nevertheless, judicial professionals face institutional and personal challenges related to working conditions that are common to all professions, including work-family balance, managing mental health and stress issues. Thus, in what concerns the individual impacts on health and well-being, the research team opted for the use of pre-existing instruments with good psychometric indicators, namely the Portuguese adaptations of OLBI - the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Bakker et al., 2004; Sinval et al., 2019), of the Work-Family Conflict Scale (Carlson et al., 2000; Vieira et al., 2014) and BaSIQS - Basic Scale on Insomnia Symptoms and Quality vof Sleep (Gomes et al., 2015). Despite the intrinsic dissimilarities between the work environments and experiences of judicial professionals and those of other public and private sector employees, these instruments aim to evaluate the existence of psychopathological symptoms and work-related stress. While the stress factors may differ between professions, the symptoms are the same for all professionals.

Challenges in analysing the mixed-methods data results

Using a mixed-methods approach to analyse the working conditions’ dimensions and impacts, the research team faced the risk of some mismatches in the collected data. Although this was not the case in the organisational working conditions’ evaluation, it did happen on individual impacts of working conditions, especially the work-family conflict and burnout effects. Survey results were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis, with the support of the statistical package for the social sciences (IBM-SPSS Statistics), allowing a characterisation of the working conditions and health situation of participants by groups and subgroups of interest. The interviews were all transcribed and analysed using MaxQda to code transcripts into nodes relating to the working conditions perception.

As an example of the obtained results, the scale used to measure burnout in the questionnaire ranked the average of participants’ responses near the midpoint or slightly above a 5 point Likert scale, far from the highest intensity of the purposed response continuum. Furthermore, although there are some differences among subgroups of relevant characteristics, like sex or judicial profession, for the majority of cases the differences were not statistically relevant. However, details that emerged from the interviews show a different picture compared to the statistical results, with professionals exhausted and with negative health consequences deriving from their work pace. For instance, one public prosecutor highlighted not only direct health consequences, such as headaches or insomnia arising from her work demands but also the worsening of previous health problems:

Q: Do you think that the work demands have had an impact on your health and well-being?

A: Yes, of course, it does. (...) Tiredness causes headaches, migraines, poor sleep, and insomnia. (...) If it causes stress, anxiety, wear and tear, it obviously interferes directly with our health. (...) I may even have high blood pressure if I had another type of job. It’s obvious that here there are also - and there certainly are - other factors, even genetic ones, but also the work, the excess of work doesn’t help to maintain ... but I also know that it is difficult to control [the high blood pressure] without medication when I perform this type of work and under the conditions in which we do it. (Female, Public Prosecutor 10, Coimbra)

Most of the interviewees acknowledge that some judges, public prosecutors and court officials were exhausted and near burnout, including themselves. And one public prosecutor even recognised that she was diagnosed with work-related burnout:

When I came back from maternity leave, I was working around 16 hours a day. The day before my return I was called to a meeting where I was told that I was going to the labour court because there were several prescriptions about to take place. Someone with experience in labour law told me that I would not be able to do in a year what I had to do in a fortnight. (…) I went weeks without seeing my daughter awake. I left the courthouse at 11:30 pm without having eaten anything at all and went home, saw my daughter sleeping and the next day at 8 am I was leaving the house to go to work. I worked Saturdays, Sundays and holidays. I walked on this register for three years. The situation was perfectly chaotic and remained that way for a long time, to the point where it led to burnout and a divorce. (Female, Public Prosecutor 07, Lisbon)

In what work-family conflict is concerned, the results of the questionnaire survey and interviews show that judicial work often interferes with and even dominates family life. However, there is a paradox between the questionnaire survey and the interviews’ results. While the first reveals the absence of statistically significant differences between men and women, the latter shows a heavier burden for women in balancing work and family life, as this quote illustrates, and that women mention different strategies to balance their work/family domains and efforts to protect family relations and domestic time from work. For example, one female judge claimed that she chooses not to go to courts or higher positions in Lisbon, to stay close to her family, with prejudice to her professional progression:

Since I started working as a judge I have always lived with this responsibility [having children]. And, therefore, it conditioned me and still conditions many of my professional choices. (…) I don’t go to the courts or positions in Lisbon. Those are the choices I make to balance my professional and personal life because I think it’s important to be present in everyday life. And those are very personal choices. My personal life has always conditioned my professional life. And it continues, despite already having a son at the age of 19, it continues to condition my choices. (Female, Judge 1, Coimbra)

Another female public prosecutor states that she tried not to bring work home and sacrifices herself:

At this point, everything is easier because my children are grown. (…) I’ve always tried to deal with everything myself (…). (…) I always told my husband [also a judge] “I’ll take care of it, I’ll pick up the kids from school and you work more, that’s it”. (…) I tried not to spend so much time in the workplace, because the work could get done. It had a totally different rhythm than my husband’s work at the time. And I tried to come home and not bring things from work. (Female, Public Prosecutor 1, Coimbra)

In this topic, a male judge recognised that the family does not interfere much in his work, because, in what concerns the family work division, his wife ends up being a little more overloaded. These strategies and associated practices reveal an underlying gender framework that ultimately harms/prejudices female judicial professionals, which is similar to the results of previous international studies (Roach Anleu and Mack, 2016).

[Does family interfere with your work?] Not much, because, in what concerns the family work division, my wife ends up being a little more overloaded. Overload because she is usually the one who takes my son to and from school. But I also do it sometimes. I say sometimes because that won’t be the rule. The rule is that my wife picks him up and not me. And so, then, everything else is shared (…). Therefore, the organization of my personal life does not interfere with work greatly, but that is also thanks to my wife. (Male, Public Prosecutor 1, Coimbra)

The big challenge is to understand if these two instruments, questionnaire and interviews, are actually measuring the same issues and how to integrate both data. Although psychological scales present a variety of items built to capture the multi-expressions of each reality and may have good psychometric qualities, the theoretical conception of that reality (that is, the theoretical concept) may not overlap with the common-sense representation. For instance, burnout measure has clinical purposes and intends to capture more than work stress or fatigue. In interviews, extreme stress or fatigue situations are described, but participants also manifest some resources to deal with that, so it is probably difficult for them to represent it in pathological terms, thus the highest response scale values are avoided.

As shown in previous international studies (Roach Anleu & Mack, 2016), it is also important to note that, the interviews show that Portuguese judicial professionals perceive the judicial work as dominant, potentially and actually overwhelming other aspects of life. The judicial work demands and dominance is normalised and seen, or experienced, as inevitable, expected, and even natural by the judicial professionals.

It’s part of the demands of the profession, that’s how it is, and it’s always been that way. But what is more perverse is that it is not only the judge who demands this of himself. It’s the peers who demand it. A judge killing himself on the job seems to be supposed to happen. He/she is well-regarded. (Male, Judge 3, Lisbon)

Judicial professionals interviewed refer to a large number of “unwritten”, normal, previously known requirements to be a professional working on the judicial system, such as being always available for urgent issues, working beyond the schedule, at night and on weekends, or constantly on a high pace. This “normalization” may also have an impact on moderating the position in the measurement scale.

The apparent instrument mismatch could also be related to the recruitment technique, the snowball sampling, and the researcher’s role. Firstly, one of the known disadvantages of snowball sampling is the bias and margin of error. Since people indicate those whom they know, and who probably have similar traits, this sampling method can have potential sampling errors. This means that the research might only be able to reach out to a small group of people. Secondly, although the interviewer kept a neutral perspective and never enforced the interviewee’s discourse, in other words, the interviewer does not agree or disagree with the interviewee, the dialogue foments a process wherein questions and statements can be clarified, answers can go deeper, and particular cases are detailed. Albeit the scale items are sentences written in the first person, it is different to evaluate an average of situations like the one depicted in the item or to relate to a concrete event.

Finally, a significant number of participants gave up precisely on the health and well-being impacts section of the questionnaire, which was the last one. Participants are probably tired, in a hurry to return to professional demands, or not comfortable with this kind of psychological scale. In future surveys, additional efforts to shorten the questionnaire length should be made, with the difficult task of balancing the need to collect relevant data while delivering a time-manageable survey that respondents feel compelled to fill out until the end.

Final remarks

This article aimed to discuss the challenges of adopting a mixed-methods approach to the study of judicial professionals’ working conditions. Based on concrete research, two main methodological challenges were identified: on one hand, the challenges of selecting and building the data collection methods and, on the other, the challenges of analysing the mixed-methods data results in a multidisciplinary context. The reflections sustained on the development of this research led to the elaboration of two main final remarks, that must be kept in mind for future work to be carried out in judicial contexts.

First, in the setting of data collection methods, it was the definition and construction of the questionnaire survey that raised more challenges in the process of integrating the different dimensions of working conditions and the contributions of different disciplines, such as Sociology of Law, Sociology of Work and Psychology, while avoiding making an overly long questionnaire. The research team decided to evaluate the impact on health and well-being using pre-existent and validated scales from Psychology, and to adapt the questions related to the organizational working conditions, considering the judicial specificities identified in the socio-legal review and professionals’ consultations. It is important to highlight the relevance of adapting the instruments to this population’s specificities. Judicial professionals are perceived as a difficult population to study (Casaleiro et al., 2021). This perceived “difficulty” can be attributed to several factors, including the judiciary’s perceived remoteness, time constraints, potential reluctance to participate in research, and concerns about confidentiality (Dobbin et al., 2001).

However, the role of the instruments used cannot be underestimated. Researchers must develop ways of measuring judicial reality, which respondents can consider interesting, relevant, and valuable to them. The achieved results show that the questionnaire response rate is associated not only with the institutional support of the management bodies of the judiciary and professional associations but also to the respondents’ interest in the theme and the uncomplexity of the measures. The theme of working conditions is of particular interest for a population that is usually forgotten from organisational labour research, considering the general dissatisfaction with several dimensions of working conditions. The receptivity to answer positively to the request for an interview is also a positive sign to collaborate with research projects, especially when the topic might be relevant to changing the public policies related to their working conditions and, therefore, improving their quality of life and professional and institutional recognition.

Secondly, quantitative and qualitative information disclosed different intensities of personal impacts of working conditions, which opened a discussion about the way judicial professionals perceive and evaluate those impacts and if there is a more suitable instrument to capture them. When invited to share their story, participants go deeper into the details and expose particular situations, which could not be evoked by scale items, or their impact intensity could be mediated by other unknown variables. “QUALIS” research team’s understanding is that the above reflection enriches more than impoverishes social studies and reinforces the use of mixed-methods designs. The qualitative results offered important pieces of evidence for the intervention and design of stress management strategies and led us to further detail in subsequent studies.

Despite the above-mentioned challenges, the research approach reveals the importance of considering the several dimensions of working conditions and their impacts, at organisational and individual levels. A core recommendation for future research must take into consideration the integration of the contribution of multiple disciplines in a research design, which allows the assessment of the causal relations between the organisational working conditions and the impacts on health and well-being, using quantitative and qualitative instruments. Complex settings call for different contributions and methods to capture a wider and deeper reality, where multiple factors can contribute to a diversified number of problems and difficulties. The judicial system embraces several layers of complexities that pose many challenges to reaching a sustained diagnosis of its reality. Therefore, the need for more integrated research is a good way to achieve it.