Introduction

This article is part of the European Erasmus+ project "Fostering social inclusion for all through artistic education: developing support for students with disabilities - INARTdis" (621441-EPP-1-2020-1-ES-EPPKA3-IPI-SOC-IN) whose general objective is to bring art and culture closer to people with disabilities and promote social inclusion through the creation of participatory artistic spaces.

Both the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2006) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2020) point to the need to ensure that persons with disabilities can enjoy all their rights on an equal basis with others. All political, educational, cultural and social institutions advocate a social model of disability in which it is the characteristics of the environment that define the person as "disabled" rather than the characteristics of the person's functioning that are important. Therefore, the focus of action towards people with disabilities should not so much be directed at the person as at the environment, creating accessible spaces in accordance with the ideas of universal design. And in this sense, we are not only talking about the accessibility of physical spaces, but also of information and knowledge, thus covering all the spectrums in which disability can manifest itself. Therefore, it is not only a question of making contexts accessible, but also of making them participatory. In this regard, it should be borne in mind that the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the global agenda will only be possible if it is ensured that persons with disabilities can enjoy all their rights on an equal basis with others, including the right of access to culture, which is an essential element for social progress and whose role is taken into account in most of the proposed goals (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2018).

However, despite the commitment of national and international agencies to the development of more inclusive contexts, there is still a long way to go. Inclusion processes are never-ending and undoubtedly complex, as they require significant transformations in the contexts where they take place (Nilhom and Göransson, 2017). Inclusion is a continuous and ongoing process of transformation that includes social awareness-raising behaviour that aims to overcome the barriers that some people encounter (Echeita, 2008). But such a process requires an inclusive vision shared by the whole community based on respect for diversity rather than homogeneity, eliminating any form of discrimination and respecting the rights of all people (Ainscow, 2012). It is true that the ethical and moral convictions underpinning the construct of inclusion are largely accepted by society (Etxeberria, 2018), but we cannot ignore the huge global north-south inequalities and the high rates of marginalisation, inequality and social exclusion in Western countries (UNESCO, 2020).

From a systemic perspective, the generation of spaces for participation becomes a key element for the development of social inclusion processes, promoting an improvement in the quality of life also for people with disabilities. These are spaces in which people interact with their peers, are accepted and recognised and can make decisions on issues that affect them.

And it is at this point where art, understood as the set of human creations which express a sensitive vision of the real and imaginary world, and therefore arts education, acquire an extremely relevant role. Arts education not only develops a set of visual, expressive and creative abilities, but also attitudes, habits and behaviours in a means of interaction, communication, expression of feelings and emotions, which allows for an integral formation of the person. In this sense, experiences with art can, on the one hand, help to build social networks that strengthen the links between people, as well as between them and the contexts in which the experiences take place. According to Calderón (2014), both the expressive dimension of art and the education of the senses and aesthetic sensitivity are fundamental in the process of socialisation, intelligence and critical judgement of people. For Whittemore (2019), art goes further as it enables autonomous learning and active participation through dialogue, making people the protagonists of their learning. Likewise, experiences through different artistic languages can be a valuable tool for people to express what they feel or communicate emotions, without predetermined schemes. According to Robledo (2018), in art there is no room for marginalisation in expression and processes of identity and belonging to the community are promoted.

In this sense, Aparicio (2014) considers that art fulfils two fundamental roles in this search for social inclusion: on the one hand, persons with disabilities become agents of socialisation that model and shape the paradigms of understanding disability and promote lifestyles associated with it; and, on the other hand, shaping legitimate spaces of expression of and for persons with disabilities and their communities.

However, the creation of inclusive artistic spaces necessarily requires the implementation of training processes for the professionals who will carry them out. In this sense, it is urgent to train professionals in competences related to inclusion and artistic creation. In addition, professionals must be competent in teamwork, in implementing flexible pedagogical-didactic actions, in inclusive leadership, in the use of inclusive technology and in the development of community support networks (Liasidou and Antoniou, 2015). Likewise, professionals require personal competences that invite them to celebrate diversity with mutual respect, to encourage dialogue, to foster critical thinking, making them feel free and comfortable in expressing their emotions and discoveries, regardless of their previous experiences in these creative environments (Alonso, 2017). There is no doubt that "the joint work of professionals and users makes it possible to develop cooperative teaching-learning exercises with a collaborative nature (group collaborative construction), in which all of us can discover how to approach the understanding of art from our own ideas and perceptions" (Aparicio, 2014:54).

Based on this idea, the INARTdis project is articulated in four workpackages (WP) that aim to respond to the four objectives set out in the project:

1. Detect the training needs in art and inclusion of professionals in art and educational institutions (WP1).

2. To assess how arts institutions can become inclusive and participatory institutions (WP2).

3. Design, implement and evaluate a training course on inclusive arts education for professionals in arts and educational institutions (WP3).

4. Design, implement and evaluate a project that generates spaces for artistic and inclusive creation (WP4).

The institutions that constitute the consortium are four universities (Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon, University College of Teacher Education Styria -Austria-, the University of Cantabria and the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), an artistic institution Thikwa -Germany- and the Association for promotion of education, culture, and sport "Education for All" (EfAS) from North Macedonia. The project also involves artistic institutions (museums, exhibition halls, theatres and auditoriums) and socio-educational institutions (primary and secondary schools, special education centres and occupational centres).

The objectives of the article are, firstly, to identify the self-perception of competences for developing inclusive arts projects by professionals of arts and socio-educational institutions; and secondly, to determine the training needs of professionals of arts and socio-educational institutions for developing inclusive arts projects.

Methodology

From a phenomenological paradigm, this mixed quantitative and qualitative research aims to explore, describe and understand the experiences lived by professionals in socio-educational and artistic institutions in relation to the process of inclusion (Wertz et al. 2011). In this case, it is a study that allows us to approach the social phenomenon for its understanding and analysis, identifying the different interactive processes that shape it in relation to the generation of inclusive artistic projects.

The professionals who participated in the study came from socio-educational centres and arts institutions in the countries involved in the project. The selection criteria for the institutions that took part in the study were: a) diversity of socio-educational centres serving students/persons with disabilities; b) diversity of art institutions taking into account artistic languages; c) institutions with inclusion projects related to art; and d) interest in the project. The professionals from these institutions were selected by the centre itself, taking into account two criteria: a) voluntariness and interest in the project and b) involvement in inclusion and/or art processes. In the end, 388 professionals took part, 22% of whom were men and the rest women. 59% of the professionals had a university education, although only 15% had training in inclusive education and 24% in art. In fact, only 21% had specialised training combining art and inclusion. The majority of professionals belonged to socio-educational institutions (65%) and the remaining 35% belonged to arts institutions. Seventy-nine percent of the participants had been working in such institutions for more than six years, although only 36% had had experience in developing inclusion processes through art.

The questionnaire, interviews and focus groups are the instruments used to obtain the data in this research.

The questionnaire consists of 31 items grouped into five dimensions: personal and professional data, inclusion processes related to art, self-perception of competences in inclusive art projects, training needs and training modalities. The questionnaire underwent an inter-judge validation process, composed of 37 experts (professors, teachers and educators from educational and cultural institutions), according to the criteria of univocity, relevance and importance. The reliability of the questionnaire was acceptable, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86.

The interview consisted of 23 questions grouped into five dimensions: personal and professional data, barriers and facilitators in inclusion processes related to art, key elements in inclusive art projects, training needs and training modalities. A total of 52 interviews were conducted with professionals from socio-educational centres (n=24) and arts institutions (n=28). The interviews were conducted via the online platform Zoom and ranged in length from 27 to 80 minutes.

Finally, 10 focus groups were conducted, in which a total of 56 professionals from the socio-educational and arts institutions participated. The focus groups were led by 1 or 2 members of the research team from each country and were conducted through the online platform Zoom. They ranged in length from 52 to 90 minutes and were audio or video recorded.

Data analysis of the questionnaires was carried out using SPSS software (v24). The qualitative data from the interviews and focus groups were analysed using the Nvivo software (v1.5).

Results

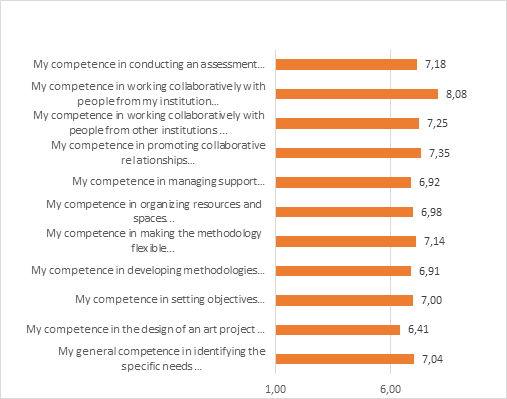

The results from the questionnaire (Graphic 1) show that the self-perception of competences related to the planning, implementation and evaluation of inclusive arts projects is medium-high (mean=7.11). The participants state that they have a good competence in developing collaborative spaces among their peers and with other institutions. On the other hand, the lowest scores are related to the design of inclusive arts projects (mean=6.41), the management of support and resources and the implementation of inclusive methodologies.

In this sense, participants perceive that their competences in creating collaborative spaces are key to the development of inclusive artistic projects.

You have to know where your own competencies ends and where you need someone who has competencies that you lack. Since we don’t carry out such projects as individuals, we need a good, heterogeneous team and then it works. PHST_13

… the need to reflect, communicate, contrast between the educational team what and how to teach, adapting to the diversity of students, teachers, resources, time and space: all this requires reflection, organisation and implementation, in constant movement. UC_01

However, participants consider that their competences to manage resources and support are conditioned by the organisation of the institution itself and subject to the availability of financial resources.

The time for the art project in general is very important. How much time do I have available? What resources do I need? How much will it cost me? Where do I get the funding from?....Who will support me and vice versa, what and which people do I need so that I can implement the art project? …I think one has to think very carefully about which sub-steps are necessary to reach the goal. PHST_02

Of course, financial resources have a big role here in order to achieve all the standards for smooth and quality involvement of people with disabilities in many activities. EfAS_01

Apart from having enough support staff, and that the material is adapted to those people who are going to come, because it is the only way for the offer to be real and inclusive. UAB_05

On the other hand, the competence to implement inclusive arts projects would be related to the need to review the concept of inclusion, as well as to have more knowledge about the specific needs of the target groups in order to adapt the project.

One of the important things is to understand the specific needs of the group to which the project is being developed, and if we manage to determine and make this assessment over the time needed to create a project, an application, or knowledge. IPL_06

Unfortunately, when we think of inclusion, we always think of the fact that there are people with disabilities whom we want to integrate in some way or who can participate, but actually inclusion means everyone. NBW_01

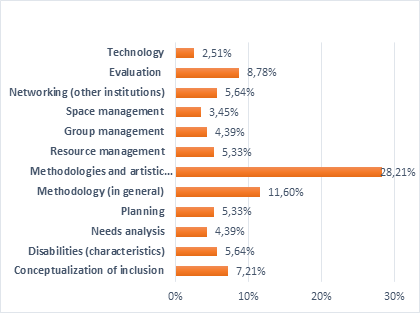

In this sense, the participants state that, in order to be more competent in implementing arts projects, (Graphic 2) they need very specific training on the methodologies that need to be developed for a project to be successful. This would involve combining the principles of inclusive education and arts education in a dialectical relationship.

Finally, it should be noted that, although both professionals from arts and socio-educational institutions perceive that they need to acquire more competences in order to implement inclusive arts projects, there are differences between professionals from both institutions. While professionals from arts institutions consider that their competences could be improved in the area of accessibility, support management, knowledge of needs or universal learning design; professionals from socio-educational institutions perceive that their competences could be improved in aspects related to the adaptation of resources to people's needs, inclusive assessment or how art can favour inclusion processes.

Conclusions

It is well known that international and national bodies, through legislation, advocate the development of inclusive processes in all spheres of society. However, the road ahead is complex, winding and sometimes very difficult. In this case, the first hurdle to overcome is the conceptualisation of artistic projects that are truly inclusive.

There is often a restrictive misconception about the meaning of inclusion (Ainscow, 2020), conditioned not only by the context in which it takes place but also by the prejudices that emerge as a result of ignorance (Forlin, 2011). This can lead to a lack of projects that are adapted to people's specific needs and thus fail to encourage people's active participation. The desirability of knowing people's specific needs becomes paramount if we want people to become protagonists of their learning within the dialogic space that artistic expression promotes (Whittemore, 2019). However, as a process, inclusion requires the implementation of measures that facilitate the participation and learning of all people from an analysis of the context, which requires the implementation of the principles of universal design to facilitate access and participation (Alonso Arana, 2017). Both cultural, educational and social institutions consider important the need to acquire knowledge and practical experiences that allow them to reconceptualise artistic projects from an inclusive perspective. This means clarifying what inclusion means, what it entails and what characterises this type of project, from the point of view of the fusion between art and inclusion and how art facilitates the process of socialisation of people (Calderon, 2014).

On the other hand, through art, social mediation processes are generated through interactions and dialogue between subjects where shared intersubjectivities and socially constructed ways of doing things (methodologies) are generated. Hence, collaboration between all people (professionals, users, students) becomes the essential element on which the proposals for inclusive artistic projects pivot. In this sense, the need for artistic training is evident, especially in the methodology used in inclusive artistic projects, which allows professionals to determine the criteria for the selection of activities, artistic languages, materials, etc. linked to the promotion of participation, group dynamics and psycho-pedagogical skills of the people who energise the project (Morón, 2011), without losing sight of the flexibility of the project to adapt to the needs at all times. Furthermore, it is considered that inclusive artistic projects should be developed in small, heterogeneous groups that allow the necessary support to be offered to people and in which mutual collaboration between participants is encouraged. Finally, the use of different artistic languages will allow people to express themselves and receive information in different ways.

In conclusion, and from a perspective of person-centred care, coordination between professionals from the different institutions that accompany people with disabilities is necessary in order to truly articulate inclusive art projects. Likewise, it is essential to develop training projects that raise awareness of the processes of inclusion, which means knowing, experimenting and experiencing inclusive processes with and for people with disabilities. But it is also essential to advise professionals on how to incorporate inclusive methodologies in the different artistic languages, in order to minimise the barriers that still exist in cultural contexts.