Introduction

The management of advanced melanoma has changed significantly over the past decade with the introduction of molecular-targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors, which markedly improved patients’ survival.1

Currently, the standard of care treatments for unresectable stage III/IV melanoma are anti-PD-1 alone or in combination with anti-CTLA4 and, for BRAF V600-mutated melanoma, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) combined with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2 The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitor, namely anti-PD-1, with BRAFi/MEKi has shown promising efficacy and gained approval in the adjuvant setting in the BRAF V600-mutated metastatic melanoma, but is associated with greater toxicity2,3and is not yet currently used in our country.

These agents frequently give rise to cutaneous adverse events (cuAEs) which can be dose-limiting and affect patients' quality of life.4,5Therefore, dermatologists are crucial in the management of these AEs in melanoma patients in order to prevent unnecessary discontinuation of life-saving anticancer therapies. Herein, we review cuAEs of small molecules and monoclonal antibodies used in the treatment of melanoma, discuss their pathophysiology and the recommendations proposed for the prevention and approach of these cuAEs.

BRAF inhibitor‑induced toxicities

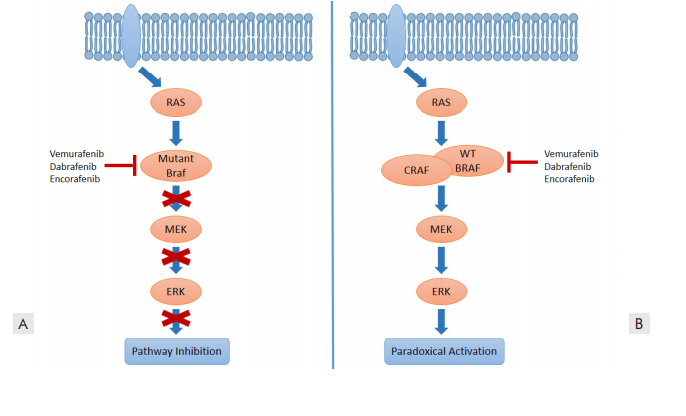

Mutations within the BRAF kinase have been identified in 40%‐60% of advanced melanomas, leading to over activation of the MAPK pathway (RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK), which regulates cellular growth, proliferation and survival.6,7BRAF inhibitors like vemurafenib, dabrafenib and encorafenib reduce signalling through this aberrant pathway.8 They have been associated with various cuAEs, broadly divided in exanthematic and proliferative. More recently the generalized use of MEK inhibitors combined with BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi/MEKi therapy) has significantly decreased the incidence of cuAEs, as they block the MAPK signalling pathway downstream.

Proliferative cutaneous toxicities

Proliferative toxicities induced by BRAF inhibitors are frequent, may be multiple, and include a broad spectrum of malignancies, ranging from benign proliferative papilloma to malignant squamous cell carcinoma or even a new melanoma.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cuSCC) is a well-known side effect of BRAF-targeted therapy. Estimated incidence for vemurafenib and dabrafenib is 4%-31% and 6%-11% respectively6 and lower for encorafenib (4%).9

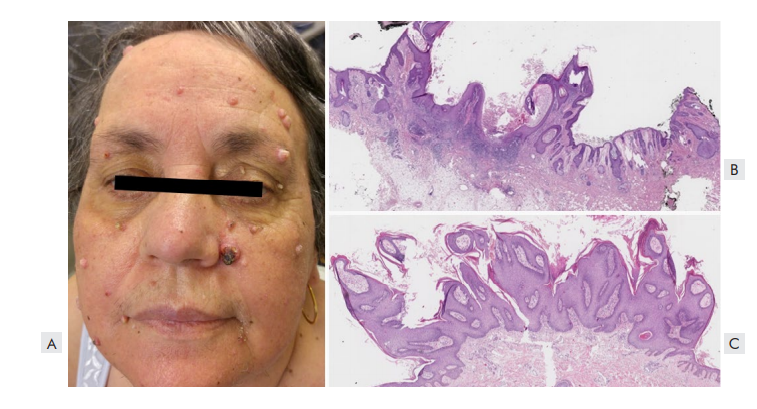

BRAF inhibitor-associated cuSCC develop more frequently within the first three months of treatment, and older patients (>60 years) are at increased risk.5,10They can appear both on sun-exposed and non-exposed areas and are typically well-differentiated (Fig. 1a,b).5,6No distant metastases have been reported to date.4

Figure 1 Keratinocytic proliferations associated with vemurafenib. (A) Clinical picture of a patient with multiple keratoacanthomas and facial verrucous keratosis. (B) Histopathological features of a keratoacanthoma, with an endophytic-exophytic, cup-shaped squamous epidermal proliferation containing a crater-like center (H&E- 12.5x). (C) Histology of a verrucous keratosis showing a papillomatous architecture with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis and absence of koilocytosis (H&E- 12.5x).

Development of CuSCC is thought to be elicited by a paradoxical activation of the MAPK-pathway in keratinocytes with wild-type BRAF and mutated RAS11(Fig. 2) This may explain why children are less likely to develop cutaneous malignancies, since they carry a lower burden of keratinocytes with UV-induced RAS mutations.12

Surgical excision is the standard therapy, usually with no need for dose reduction or treatment discontinuation.4,5In patients with multiple cuSCC, oral acitretin may be useful in preventing new carcinomas.13,14However, concomitant treatment with MEKi reduces the incidence of cuSCC by blocking the MAPK-pathway downstream.15

Patients should have dermatologic evaluations before and during targeted therapy (for example, every 2 to 3 month). Additionally, given the potential risk of mucosal squamous carcinomas, the follow-up must also include a close examination of the oral, genital and anal areas.

Figure 2. Paradoxical activation of MEK/ERK signaling induced by BRAF inhibition. (A) BRAF-inhibitors suppress MAPK/ERK activation in the presence of the BRAF V600E mutant. (B) In wild-type BRAF cells, BRAF-inhibitors can enhance MAPK activation via paradoxical activation mechanisms that increase RAF dimerization and induce kinase transactivation.

Verrucous keratosis

Verrucous keratoses are pre-malignant hyperkeratotic papules that clinically resemble viral warts or small keratoacanthomas (Fig. 1A,C).5,6In patients on monotherapy, they occur in up to 79% of patients receiving vemurafenib, 49%-66.4% of patients on dabrafenib4,6and in 8% on encorafenib.9

These lesions, which are also caused by a paradoxical activation of the MAPK-pathway,4 generally appear on sun-exposed and unexposed areas after 6-12 weeks of treatment.6

Despite their benign histopathological features, verrucous keratoses carry the same mutations and a similar immunohistochemical profile of cuSCC.5It is believed that they have the potential to develop into cuSCC.

Verrucous keratosis can be treated with cryosurgery, but they become less frequent with time.5 Acitretin may be also useful for prevention.13,14

Melanocytic lesions

BRAF-inhibitors have been associated with dynamic changes in melanocytic nevi, including modifications in size and color (Fig. 3), involution, appearance of eruptive nevi and development of atypical melanocytic lesions or new primary melanomas.16 These changes can be observed in up to 55% of nevi using digital dermoscopy, and most occur within the first 6 months of treatment.4 Whereas eruptive nevi can be seen in children on BRAFi, dysplastic nevi or melanomas seldom occur in this population.12,17

It is plausible to assume that melanocytic nevi that involute harbour the BRAF V600E mutation that is targeted by BRAFi therapy, whereas nevi that grow in size or develop dysplastic features have the BRAF wild-type.16,18

New primary melanomas have been reported in 2.5%-21% of patients in monotherapy, with a median treatment duration of 14 weeks.5,6,19Most seem to be originated in a pre-existing nevus and are BRAF wild-type, suggesting that paradoxical activation of MAPK pathway may also contribute to their development.5

Regular dermatologic evaluation with clinical and dermoscopic total body examination is, therefore, crucial to identify BRAFi-associated melanocytic changes and, specially, early malignant lesions.4 Follow-up with digital dermoscopy and total body mapping should be considered in patients with atypical or multiple nevi and all nevi with atypical changes must be excised.

Non-tumoral cutaneous toxicities

Exanthematous rash

The most frequent toxicity of BRAFi is an exanthematic eruption, commonly a papulopustular eruption affecting the face, scalp and trunk. It occurs 2 to 6 weeks after onset of treatment, is dose-dependent and usually clears with dose reduction. It is most common with vemurafenib but also occurs with other BRAFi.

Phototoxicity

Phototoxicity is a common adverse event of vemurafenib (up to 52% of patients) but less frequent with dabrafenib and encorafenib (1%-3%).4,20,21

Clinically, it presents as an immediate sensation of heat and burning on sun exposure and solar urticaria-like erythema (without pruritus).5,21Patients also develop a delayed sunburn-like reaction that can range from mild erythema (Fig. 4) to painful blistering (12% of patients under vemurafenib have grade 2 or 3 reactions).5,21

Phototesting has shown that UVA radiation alone triggers both the immediate and the late reaction.21 UVA irradiation of BRAFi produces a UVA-absorbing photoproduct that might be responsible for photosensitivity.20 Studies also suggest that vemurafenib has an inhibitory effect on UV-induced DNA damage repair.20 In addition, vemurafenib also inhibits ferrochelatase, resulting in elevated protoporphyrin levels.21

Before treatment, patients should be instructed about photoprotective measures, including sun-avoidance, protective clothing, and frequent use of broad spectrum sunscreens (UVA and UVB protection).4,5It is also important to inform patients that UVA maintains the same intensity all day and is able to penetrat e glass window. Photosensitivity disappears rapidly after drug discontinuation.21

Acute radiodermatitis has also been reported in patients treated with concurrent BRAFi and radiation therapy,6 mostly with vemurafenib. Therefore, BRAFi should be interrupted during radiotherapy.4

Hand-foot skin reactions

Hand-foot skin reactions (HFSR) have been reported in 15%-45% of patients receiving BRAFi therapy.6 HFSR represent a spectrum of clinical entities affecting the palms and soles, including: palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE) and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (PPH). PPE presents with painful, edematous erythema not restricted to areas of friction.15 PPH manifests with tender, hyperkeratotic, yellowish plaques mainly located on pressure points, such as heels and metatarsal regions.15 Encorafenib seems to induce PPE and PPH more often than vemurafenib or dabrafenib. Concomitant administration of a MEKi reduces their incidence.9

HFSR are dose-dependent and may impact patient's quality of life and ability to walk. Pain from PPH usually improves within 4-6 weeks, however PPE may progress to formation of blisters and ulceration.4

Patients should be advised to wear comfortable footwear to avoid rubbing and to apply keratolytic skin moisturizers with urea, salicylic acid or ammonium lactate.5 Topical corticosteroids (TCS) or lidocaine cream should be used for grade ≥2 reactions.22 Oral retinoids are a treatment option for extensive PPH.5 In grade 3 PPE, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gabapentin and opioids are often necessary for pain control.22

Transient acantholytic dermatosis

Grover’s disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is one of the most common dermatoses induced by BRAFi (up to 45% of patients).6 It generally consists of small, scally, pruritic, erythematous-brown papules, mainly affecting the trunk and proximal upper arms (Fig. 5).4 The main histological findings are acantholysis and dyskeratosis.4 Grover’s disease can be treated with emollients, topical keratolytics and corticosteroids.4 Oral acitretin may also benefit this situation.5

Figure 5 Transient acantholytic dermatosis induced by vemurafenib, with crusty erythematous-brown papules on the trunk.

Panniculitis

Panniculitis has been described in approximately 2% of encorafenib, 2.5% of dabrafenib and 11% of vemurafenib-treated patients,5,9used either in monotherapy or in combination with MEKi.21

Clinically, BRAFi-induced panniculitis is characterized by multiple tender erythematous nodules, usually with a predilection for the lower limbs (Fig. 6a), although the arms and trunk are sometimes involved as well.4,23The time of onset is variable, ranging from 3 to 324 days (median of 15 days).24,25Systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia are frequently observed.23

Skin biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude infectious panniculitis or metastatic melanoma. Different histological patterns have been described. Neutrophilic lobular panniculitis is the most common,23but a lymphocytic or mixed inflammatory infiltrate and septal involvement (Fig. 6B) is also frequent.23 A predominant lymphocytic infiltrate has been associated with a larger time gap between initiation of BRAFi and symptoms onset.24,25

Panniculitis can be treated symptomatically with NSAIDs, TCS and adequate rest.4,23Severe cases may require a short course of systemic corticosteroids and/or temporary BRAFi interruption.4,23

However, most patients respond to conservative medical treatment without the need to reduce or discontinue targeted therapy.23

Other manifestations

Keratosis pilaris has been observed in almost all patients during the first weeks of treatment with BRAFi, especially in monotherapy. Lesions present as erythematous follicular hyperkeratotic papules on the upper arms, thighs and buttocks (Fig. 7).4 Treatment options include topical retinoids and keratolytics, which provide comforting relief.4

Other dermatosis associated with BRAFi include pruritus, seborrheic dermatitis, lichenoid keratosis, cystic facial eruptions, pyogenic granuloma, granulomatous dermatitis, Sweet syndrome, alopecia and oral mucosal hyperkeratosis.4-6,26

Severe cutaneous adverse reactions such as drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have been rarely described, however these require prompt recognition, treatment discontinuation, and aggressive management.4,5

DRESS syndrome has been also documented in patients treated with vemurafenib who received prior immunotherapy.11,27This rash is likely due to a non-allergic inflammatory reaction, resulting from the persistent activation immune system by the checkpoint inhibitors (CPI).11

MEK inhibitor‑induced toxicities

The emergence of BRAFi resistance led to concurrent administration of BRAFi and MEKi to block MAPK pathway downstream.8 Currently, there are three FDA and EMA approved combinations: dabrafenib plus trametinib; vemurafenib plus cobimetinib; and encorafenib plus binimetinib.8 MEK inhibitors are also used as monotherapy in children with central nervous system tumors.12

Acneiform eruption

Papulopustular or acneiform eruptions are among the most prevalent adverse effects of MEKi, occurring in 13%-82% of patients.5,28-30This rash usually develops early during treatment (often within the first weeks), and in a dose-dependent manner.31 It is characterized by inflammatory papules and pustules, typically affecting seborrheic areas.31 These eruptions are commonly monomorphic, without comedones, and are often associated with pruritus.31Rupture of pustules can result in crusting and secondary bacterial infections.11

At present, the pathophysiology of MEKi-induced acneiform eruptions remains poorly understood. It has been proposed that they may be associated with an abrupt blockage of MAPK pathway.31This may explain why the addition of a BRAFi significantly reduces the incidence (3%-14%) and delays the onset of these eruptions. A recent study found that MEKi and Cutibacterium acnes act synergistically on keratinocytes to induce IL-36γ and IL-8, promoting skin inflammation and papulopustular eruptions.32 In addition, children and teenagers are more likely to have acneiform eruptions (67.4%-87%) than adults, suggesting that a predisposition to acne along with high sebaceous gland activity may be a risk factor.12

Acneiform eruptions are rarely life-threatening but they affect cosmetically sensitive areas and may impair the patient's quality of life. In severe cases, dose reduction or interruption may be necessary.31 Current treatment options include topical low-potency steroids, antiseptics and antibiotics (1% clindamycin).5 In more severe cases, oral doxycycline or isotretinoin should be considered.31

Nail toxicities

Patients treated with MEKi may develop paronychia and periungual granulomas.11,33Paronychia typically develops after several weeks or months of treatment, and can evolve into overgrown granulation tissue (pyogenic-like granulomas).11,33These lesions affect mostly toenails or thumbs, and are more common in children, probably due to higher physical activity and frequent exposure to trauma.12,33 Usually they are not severe but can still be very distressing for the patient, especially when they persist for a long time.

MEKi may also induce mild to moderate changes in the nail bed and matrix, leading to onycholysis, brittle nails, and slower nail growth.33

To prevent nail adverse effects of MEKi, specific measures can be taught to patients: avoidance of repeated trauma or nail manipulation and prolonged contact with water; regular nail trimming; use of protective gloves, cotton socks and comfortable, wide-fitting footwear.11,33

Paronychia caused by MEKi is not initially infectious, but renders the nail folds very sensitive to infection.33 Therefore, antiseptic soaks are recommended, with additional topical or systemic antibiotics or antifungals in case of superinfection. Non-infected paronychia can also be treated with potent TCS.

Standard treatment for pyogenic granuloma is surgery, but several conservative modalities have been developed over time, including cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, chemical cauterization, laser therapy and sclerotherapy.34

Other manifestations

Patients treated with BRAFi+MEKi experience less cuAEs, which generally occur after a longer treatment course. Compared with BRAFi monotherapy, there is a significant reduction in the development of cuSCC (2.0%-4.5%), verrucous keratosis (2%-7%), keratosis pilaris (4%-7%), PPH (2%-9%) and alopecia (6%-13%).5,11,35Other hyperkeratotic lesions such as Grover’s disease and oral mucosal hyperkeratosis tend to regress upon addition of MEKi. This effect is explained by the inhibition of the paradoxical activation of MAPK pathway in BRAF wild-type cells through MEKi coadministration.11

Immunotherapy-induced toxicities

Monoclonal antibodies that block immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), allow T cells to recognize and destroy cancer cells.36,37In addition to tumor regression, CPI also compromises self-tolerance, leading to the development of a broad spectrum of immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

Cutaneous toxicities are the most frequent and earliest irAEs, affect 18%-64% of patients38 and are usually graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0).

Maculopapular rash

Maculopapular exanthema represents the most frequent cutaneous toxicity of CPI. This eruption has been reported in 24%-68% of patients under anti-CTLA-4 therapy and in 14-20% of patients with anti-PD-1.38 Nevertheless, the frequent use of the non-specific term “rash” in reports of cuAEs, makes it difficult to estimate its true incidence.

The rash is usually pruritic, morbilliform and typically involves the trunk and extensor surfaces of the extremities. It presents early in treatment, generally after 3-6 weeks, and appears to be dose dependent.38Most cases are mild or moderate in severity, affect less than 30% of body surface area (grade 1-2), and are self-limited39. In 1.2%-4% of patients, the rash is considered severe (grade 3)4,38and it may be the initial presentation of a potentially life-threatening skin reaction.40-42

Histopathologic features include a superficial, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate predominantly with eosinophils and CD4+ T cells, with or without epidermal spongiosis and papillary dermal edema.5

The treatment is largely symptomatic. Grade 1 and 2 rash can be treated with emollients, high-potency TCS and oral antihistamines, without discontinuation of immunotherapy.4,39In severe cases (grade 3), oral corticosteroids (0.5-2 mg/kg) may be considered for 2-4 weeks, and immunotherapy should be withheld until rash is back to grade 1.4Oral corticosteroids do not hinder anti-tumour response and selectively down-regulate severe cuAEs.5

Pruritus

Pruritus is reported in 25%-35% of cases with anti-CLA-4 therapy, 13%-20% with anti-PD-1 and 33% with the combination.38 Nonetheless, high grade pruritus occurs in less than 2.5% of patients.38It can occur alongside a cutaneous eruption or as an isolated condition.

Pruritus can be managed with emollients, TCS and oral antihistamines. Aprepitant, doxepin and pregabalin could be considered for refractory patients.4,5

Vitiligo

Vitiligo has long been associated with cutaneous melanoma but it has been increasingly reported in patients undergoing immunotherapy. Its incidence reaches 28% (8%-28%) in anti-PD-1 therapy and 11% (4%-11%) in anti-CTLA-4 therapy.4

Estimated risk is 10-fold higher than in the general population. Nevertheless, immunotherapy-related vitiligo is rarely reported in patients with other cancers (mainly non-small cell lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma).38,43

It is characterized by multiple flecked depigmented macules evolving into larger patches on photoexposed skin or around cutaneous metastasis (Fig. 8).37 Vitiligo generally appears after months of therapy, does not seem to be dose related and is frequently associated with other cutaneous toxicities (lichenoid reactions and eczema).38,43Depigmentation of melanocytic lesions has also been reported.4,5

During treatment with CPI, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells are activated against antigens shared by normal melanocytes and melanoma.43,44The development of vitiligo has been associated with improved therapeutic outcomes and survival.38

Vitiligo persists after immunotherapy cessation.39Treatment is not necessary, but TCS or calcineurin inhibitors could be used to induce repigmentation.4,5,38Patients should also be advised to use appropriate photoprotection as they are more susceptible to sunburn.38

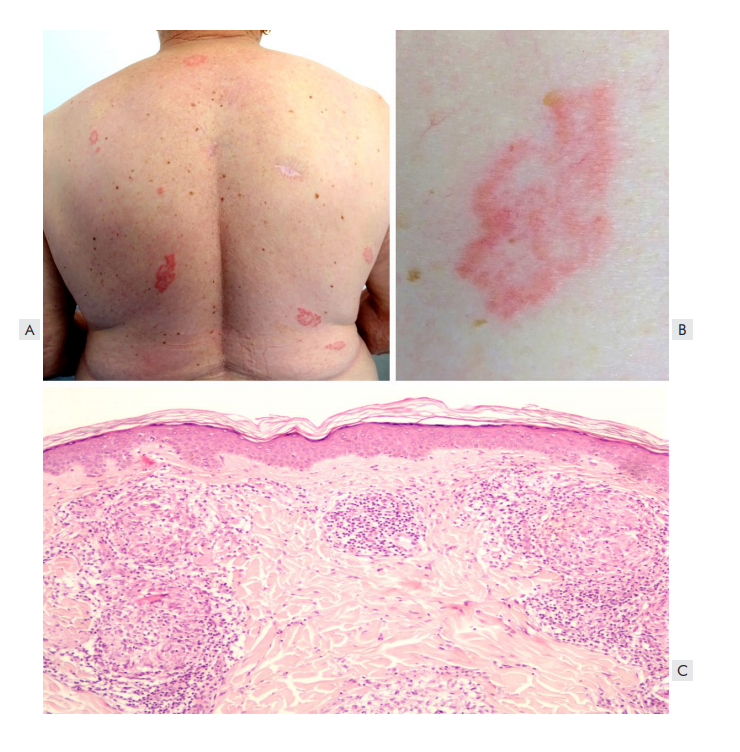

Lichenoid eruption

Lichenoid eruption has been reported in 0.5%-17% of patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy, with a mean time to onset of 6-12 weeks post-treatment initiation.5,38,45

Pathogenesis remains poorly understood, but may result from activation of monocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages associated with antitumor response to immunotherapy or from an immune response to an unknown antigen.45

Patients commonly present multiple, discrete, erythematous or violaceous papules and plaques, sometimes resembling lichen planus (Fig. 9).4,5,38They are frequently pruritic and most commonly appear on the trunk, with relative sparing of mucosal surfaces.38

Histopathologic features are similar to those of idiopathic lichen planus, except for an increased abundance of CD163-positive cells, indicating a macrophage-monocyte lineage.11,45

Mild to moderate eruptions are managed with high potency TCS.4,5Severe cases may require oral corticosteroids and CPI interruption.38,39Alternative treatment options include acitretin and phototherapy.39

Figure 9 Lichenoid eruption induced by nivolumab. Erythematous to hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on the tights (A) and legs (B). (C) Lichenoid reaction pattern including hypergranulosis, basal cell vacuolization and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermo-epidermal junction (H&E- 400x).

Bullous pemphigoid-like eruption

Several case reports have described bullous pemphigoid (BP)-like eruptions following anti-PD-1 therapy4-6,38Reported incidence varies between 1% and 5%.38,39 Onset seems to be variable, usually delayed with an average of 14 weeks (range 4-84) after treatment initiation.38

After an initial non-bullous phase with pruritus, generalized or localized tense blisters typically appear on the trunk and extremities38,39and in 10%-30% of cases also on the oral mucosa.38Suspicion of BP-like eruptions should arise in patients with intractable pruritus that is not explained otherwise.

Pathomechanism of immunotherapy-related BP is not yet clear. However, generation of pathogenic autoantibodies supports that inhibition of PD-1 can activate B cells, perhaps through the dysregulation of B-cell regulatory T cells.39

Histopathology and immunofluorescence have classical features of BP39 and anti-BP180 and anti-BP230 antibodies have been detected in the serum and are helpful in monitoring treatment response.39

Immunotherapy-related BP may persist for several months after discontinuation of CPI, consistent with a durable state of immune activation.38Early diagnosis and prompt treatment may prevent the need for withdrawal of life-saving immunotherapy. Grade 1 BP-like eruption may respond to high-potency TCS, nonetheless oral corticosteroids (prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg) are often needed in grade 2.39Rituximab should be considered in grade 3 and 4.38,39It has been shown to be effective and safe. Intravenous immunoglobulin is another option for resistant disease.39Doxycycline may also be used in patients with less severe BP.39

Other manifestations

Both de novo and exacerbated psoriasiform dermatitis appearing within 3 weeks of anti-PD-1 treatment has been described4,5,38and strongly correlates with anti-tumor response. PD-1 blockade augments Th1 and Th17 activity, which play an important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.4

Other cutaneous manifestations includie photosensitivity, radiosensitisation, neutrophilic dermatosis (pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcerations, Sweet’ syndrome), sarcoidosis (Fig. 10), xerosis, alopecia areata and stomatitis.4-6,38,46

Rarely, life-threatening conditions such as SJS, TEN, and DRESS may develop.40-42In such cases, treatment with immunotherapy should be immediately and permanently discontinued.

Figure 10 Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. A) Disseminated erythematous annular plaques on the trunk. B) Detail of an annular plaque composed of grouped erythematous papules with a yellowish hue. C) Organized collections of epithelioid histiocytes on the superficial and deep dermis, with scattered multinucleated giant cells (HE x100).

Combined CTLA4 and PD-1 blockade

The concurrent use of ipilimumab and nivolumab has demonstrated higher response rates, but at the expense of increased adverse effects. According to recent studies, cuAEs are observed in 70%-88% of the patients,4,5,38most commonly non-specific rash, pruritus, lichenoid reactions and vitiligo.47They appear earlier and develop more rapidly compared to anti-PD 1 monotherapy.47

It is hypothesized that ipilimumab accelerates the lymphocytic damage to peripheral tissues, thereby causing cutaneous eruptions earlier. 47

Conclusion

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy have significantly improved prognosis of advanced melanoma patients. With expanded use of these drugs, a range of cuAEs have emerged. Although the vast majority is low-grade, many cause significant morbidity and there are rare life-threatening conditions. Cutaneous reactions from immunotherapy are milder than the ones caused by targeted treatment, but they can be long-lasting and more difficult to manage.

Early diagnosis of cuAES and prompt intervention can reduce the discontinuation of dermato-oncologic therapies. Preventive measures and surveillance (for example, follow-up visits every 2 to 3-months) may also significantly improve tolerance to these treatments and drug survival. Dermatologists should take the lead in dealing with these cutaneous manifestations in close collaboration with oncologists in order to ensure optimal patient care.