Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) or atopic eczema is an inflammatory chronic itchy skin disease. It is multifactorial in origin and occurs in genetically predisposed subjects.1 AD is described as a global burden impacting the quality of life of patients.2-4In sub-Saharan Africa the prevalence of AD still remains unknown. Most studies are partial, fragmented5,6and are interested generally on clinical and therapeutic epidemiological aspects. Thereby the impact of this disease on quality of life (QoL) is rarely assessed. To overcome this unmet need we decided to conduct this study with the main objective of assessing the impact of AD on the QoL of children through the CDLQI score.

Population and Methods

This study was carried out in the dermatology consultation unit of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire from Treichville. It was a cross-sectional, descriptive and analytical survey, carried out on the basis of prospective recruitment. Our investigation occurred from December 2017 to June 2018 (i.e. 07 months). The study population concerned patients consecutively observed during the consultation in the dermatology department whose parents gave a written informed consent to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were children of all sexes, aged 5 to 16, observed in the consultation with a diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. The following parameters were studied: sex, age, place of residence, history of personal and family atopy, treatments and the items of SCORAD and CDLQI.

Results

II.1. Epidemiological data

In our study, the sample consisted of 30 girls and 30 boys, i.e. sex ratio (M / F) of 1. The average age of the patients in our series was 8.8 ± 3.2 years with extremes 5 and 16 years old. The age group of 5 to 9 years was the most represented (57%). The majority of patients lived in the municipalities of Treichville (50%) and Yopougon (15%), two municipalities within the city of Abidjan.

II.2. Clinical data

More than half of the patients (68.3%) had a family history of atopic disease in our series, allergic rhinitis in 35% of cases, asthma in 21.7% and allergic conjunctivitis came third (11.7%). On a personal level, more than half of the patients had a history of atopy (76.7%): allergic rhinitis in 38.3%, asthma in 25% and allergic conjunctivitis in 13.3%. All patients were under topical therapy.

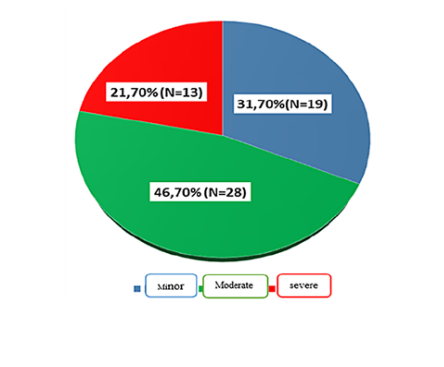

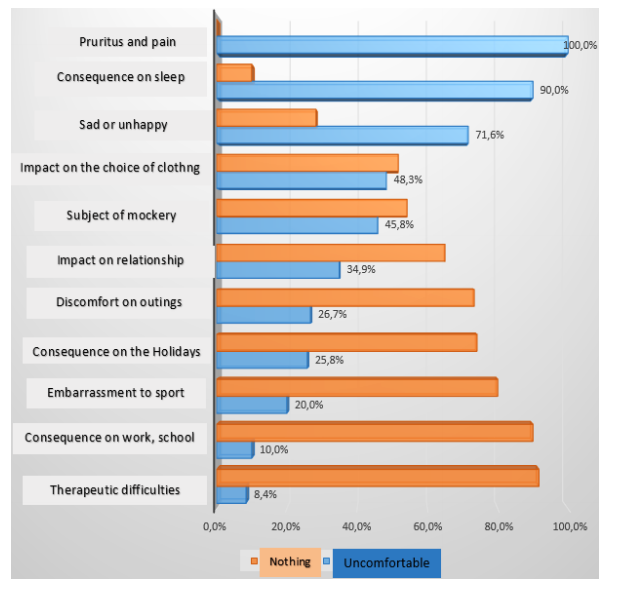

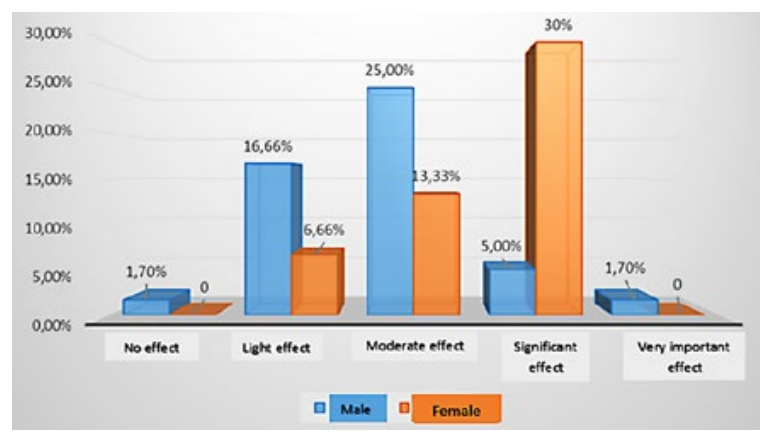

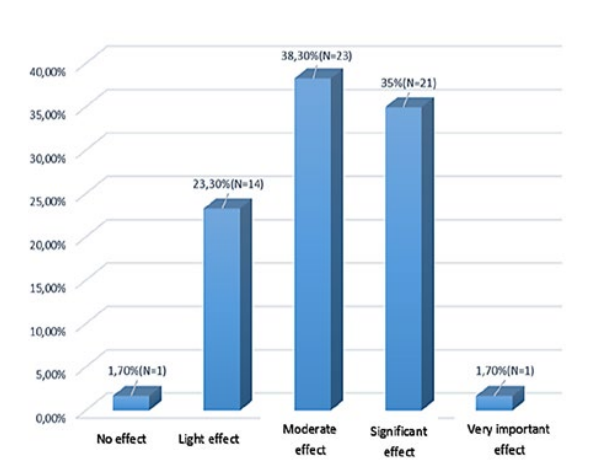

The mean SCORAD was 24 with extremes of 9 and 47. The SCORAD was minor in 31.7%, moderate in 46.7% and severe in 21.7% of cases (Fig. 1). As for the impact of CDLQI items, all the children were bothered by pruritus and the effect on their QoL was very important in more than half of them (65%). Sadness and insomnia had a significant effect on more than one-third (38.3%) of children (Table 1). AD had consequences on sleep in 90% of children. The effect of dermatitis on school performance was noted in 10% of children (Fig. 2). The mean CDLQI score was 9.9 with extremes of 1 and 24. Almost all patients had an impact of AD on their QoL. This effect was slight in 23.30%, moderate in 38.30%, significant in 35% and very important in 1.70% of cases (Fig. 3).

The deterioration in QoL was significant in 30% of girls and moderate in 25% of boys (Fig. 4).

Table 1: Distribution of CDLQI items according to the importance of the effect on quality of life.

| Items | Very large effect | Large effect | Moderate effect | Low effect or no effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pruritus | 65.0% | 23.3% | 11.7% | 0.0% |

| Sad or unhappy | 13.3% | 38.3% | 20.0% | 28.3% |

| Relationship Change | 3.3% | 18,3% | 13.3% | 65.0% |

| Special clothing | 3.3% | 21.7% | 23.3% | 51.7% |

| Embarrassed to Go Out | 0.0% | 10.0% | 16.7% | 73.3% |

| Embarrassed to do Sport | 0.0% | 3.3% | 16.7% | 80.0% |

| Consequence on school | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.0% | 90.0% |

| Bad holidays | 1.7% | 13.8% | 10.3% | 74.1% |

| Funny names | 3.4% | 13.6% | 28.8% | 54.2% |

| Insomnia | 31.7% | 38.3% | 20.0% | 10.0% |

| Treatments | 0.0% | 1.7% | 6.7% | 91.7% |

Figure 3: Distribution of patients according to the intensity score of CDLQI (children quality of life index) (%).

II.3. Analytical study

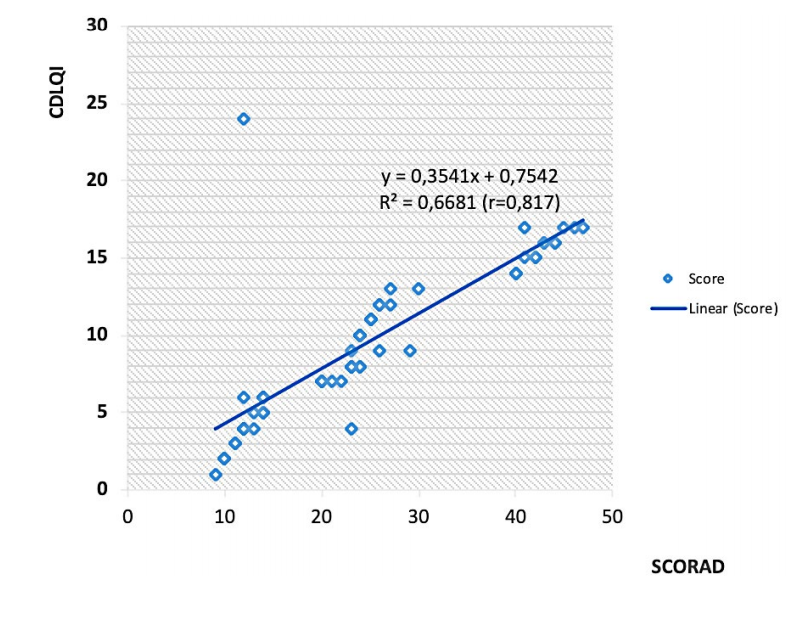

He had a strong relationship between CDLQI and SCORAD (Pearson correlation: R = 0.81 p = 0.00001) certifying the existence of a positive correlation between these two instruments, the scores of CDLQI and SCORAD (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Various studies have demonstrated the genetic influence of AD. Indeed, 50% to 70% of AD patients have a parent or a first degree relative with AD, asthma or allergic rhinitis.7 In our study, the family atopy rate was similar to that of Ly F et al in Senegal (47%).8 On a personal level, more than half of the patients had a history of atopic disease (76.66%) in our series. Indeed, the association of several atopic manifestations in the same patient is classic but fickle. These manifestations usually appear in the following order, called "atopic march”: AD, food allergy, asthma, allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis.9

The mean SCORAD was 24 with extremes of 9 and 87, with moderate and severe cases, respectively, in 46.7% and 21.7%, outnumbering severe forms usually reported in the literature, which represent less than 10% of affected individuals.10,11This data calls the attention to the severity of AD in African countries, even in younger populations.

The natural history of AD is characterized by a succession of relapse and remission periods. Indeed, the assessment of disease severity is important for therapeutic management. Questionnaire items within the CDLQI having obtained the highest scores, i.e. the variables which have the most affected quality of life were pruritus, insomnia and sadness, similarly to the study of Kim et al.12 AD is an inflammatory dermatosis which has pruritus as its main symptom. Pruritus has a nocturnal upsurge in some children often causing sleep disturbances. These children sometimes sleep with their parents (cobeding), a situation that is sometimes the origin of family conflicts, including sadness in children.13 Chronic inflammation, pruritus and insomnia can lead to absenteeism or bad performance at school. The mean CDLQI score was 9.9 with extremes of 1 and 24. Almost all of patients (98.3%) had an impact of AD on their QoL. This effect was slight in 23.3%, moderate in 38.3%, important in 35% and very important in 1.7% of cases. Our results are similar to those obtained in studies carried out in Brazil and Spain where the mean score was 9.5 and 9.4, respectively.14,15Other studies have found a score lower than ours such as the study conducted in Brazil and Sweden where the average score was 5.4 and 6, respectively.16,17QoL of affected subjects and their families is often much altered due to pruritus, sleep and mood disturbances. Overall, according to some studies, QoL is more affected during AD than during asthma or childhood diabetes.13 Impact of childhood AD on QoL is usually independent on gender, but in our series the impact of AD seemed higher in girls. It can be explained by the fact that the aesthetic damage of this chronic inflammatory disease and its visibility is of much greater concern among female children. Our study showed a significant relationship between the quality of life (CDLQI) and the severity of the disease (SCORAD), which is in agreement with studies of Ben Gashir et al in the United Kingdom (England).18 Indeed, AD affects QoL due to its visible character, the intensity of erythema and pruritus leading to scratching lesions. But, according to some studies, the deterioration in QoL is not always correlated with the severity of the disease. It would depend on the personality of the patient, the environment and quality of care.19

Conclusion

This study in which most of the patients were aged 5-9 years reveals the very significant impact of AD on the QoL of children in Abidjan, mainly through pruritus, insomnia and sadness. It also strengthens the link between the severity of the disease and the importance of QoL impairment. Taking charge of this affection must therefore be global, integrating therapeutic intervention with education, for which a prospect of creating a school of atopy in Côte d’Ivoire would be welcome.