INTRODUCTION

Occupational contact dermatitis (OCD), which encompasses irritant, allergic, and immediate reactions, is a limiting factor of professional activities and a cause of discomfort that can lead to decreased work capacity and absenteeism.1,2OCD represents the main occupational skin disease (up to 70% of cases)3-5and is also one of the main occupational diseases.

Chromium has been responsible for occupational skin disease, both irritant and/or allergic contact dermatitis. Industrialization and new materials used currently have resulted in increased exposure to chromium ions.6,7The main sources of exposure to chromium include cement, leather products, anti-corrosive paints, cleaning products, metal alloys, cosmetics, mobile phone components, implants / prosthetics, among others.1,7-12

The history of chromium as an allergen has several decades and is associated with different interventions to minimize exposure to this metal, which have managed to gradually change the panorama of the epidemiology of chromium allergy.6,7,12-16In Denmark, in 1983, the implementation of obligation to add ferrous sulphate to cement reduced the concentration of water-soluble chromium to values <2 ppm. Then Finland in 1987 and Sweden in 1989 implemented the same measure7 and, in 2003, the European directive restricting also marketing and use of cement containing hexavalent chromium in concentrations> 2 ppm came into force,17 a directive that was taken into action in Portugal in 2005.18

In 2003 the concentration of hexavalent chromium in leather, namely in protective gloves, was limited to <10 ppm and in 2009 further reduced to <3 ppm. The decision to limit hexavalent chromium below 3ppm in leather products that contact the skin was finally adopted by the European Commission in 2015.7,17

It is interesting to note that contact allergy to chromium is usually concomitant with other allergies, especially other metals.12 However this is not due to cross-reactivity but mostly to the synchronous presence of other metals in sensitizing products.7 The aim of the study is to carry out an epidemiological analysis of the prevalence of contact allergy to chromium and evaluate if the regulatory measures implemented so far in Portugal have been enough to lessen the problem of sensitization to chromium.

METHODS

This is a retrospective study conducted for 10 years (2009 to 2018) at the Cutaneous Allergology of the Department of Dermatology, Hospital and University Center of Coimbra (Portugal) and involved all consecutive patients who underwent epicutaneous patch tests for the study of suspected allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) or other delayed hypersensitivity reactions with skin involvement.

All patients who had a reactive epicutaneous test for chromium were included and the following parameters evaluated: gender, age, personal history of atopy, main location of the lesions, time of evolution of the lesions, occupation, other positive allergens (namely other metals and rubber allergens usually related to concomitant exposure in an occupational setting), clinical and occupational relevance. The population with chromium allergy was compared with the general population tested by the MOAHLFA index (male, occupational dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hand dermatitis, leg ulcer/dermatitis, face dermatitis and age > 40 years).

Epicutaneus tests

All patients were tested with the European baseline and additional series, according to the medical history and the tasks they developed. Allergens from Chemotechnique (Chemotechnique Diagnostics®, Vellinge, Sweden) or Trolab allergens® (Almirall GmbH, Germany) were applied for 48 hours on the back using Finn Chambers® (Epitest Ld, Almirall) or IQ Chambers® (Chemotechnique Diagnostics®, Vellinge, Sweden). Readings were performed at day 2-3 and day 4-7, according to European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD) guidelines.5 Epicutaneous tests or open tests were sometimes carried out with products brought by the patient, collected in the workplace or in his personal environment. Reactions were considered positive if at least erythema and infiltration were observed (1+ or more intense). Positive reactions were interpreted as having current, past or unknown relevance or explained by cross-reactions.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, the program IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 was used. Quantitative variables were tested for normality using Shapiro Wilk test. Correlation between variables were analyzed with Pearson’s or Spearmans’s Correlation Coefficient. The X2 test of independence was used to compare categorical varia-bles. Fisher’s exact test was applied when the expected value in any of the cells of contingency table was < 5. Significance level was esta-blished at 0.05.

RESULTS

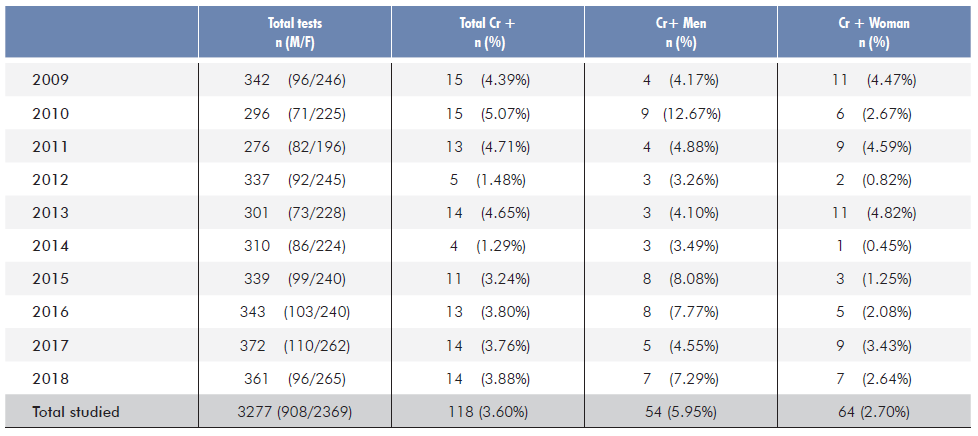

Between 2009 and 2018, 3277 individuals were studied, 2369 females (72.29%) and 908 males (27.71%), 621 of whom (18.95%) with criteria for occupational contact dermatitis.

Chromium allergy was found in 118 (3.60%) patients, 64 fema-les (54.4%) and 54 males (45.76%), representing respectively 2.70% and 5.95% of all the women and men tested in this period. The average age of females was 46.63±14.67 and males 54.06±13.13 years (p=0.004).

No statistically significant correlation was found in the number of cases over time (rho=-0,265; p>0,05). This remained true, when preforming the analysis for age groups and gender (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribuition of positive tests to potassium dichromate (Cr) by year and gender among all patchtested patients.

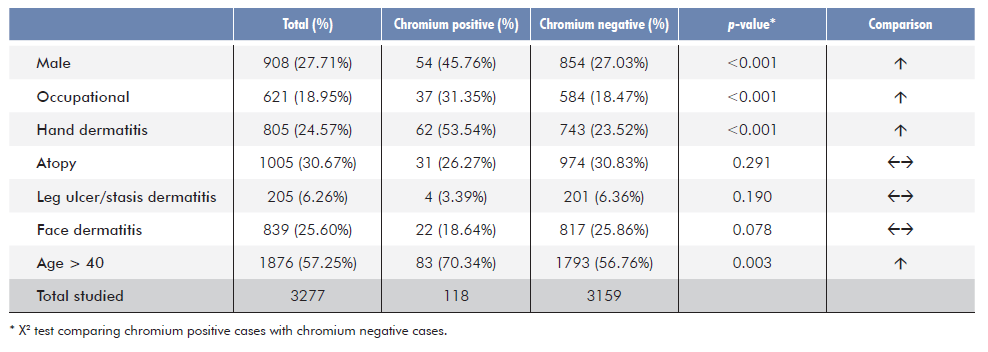

When comparing the MOAHLFA index of patients with and wi-thout chromium allergy, we found that among chromium sensitized patients the percentage of male patients was statistically more frequent (45.76% vs 27.03%; p<0.001), as well as occupational dermatitis (31.35% vs 18.47%; p<0.001), hand dermatitis (53.54% vs 23.52%; p<0.001) and age above 40 years (70.34% vs 56.76%; p=0.003).

The history of atopy was found in 31 patients with chromium allergy (asthma in 8, rhinitis in 4, atopic dermatitis in 13, asthma and rhinitis in 4, asthma and atopic dermatitis in 1 and rhinitis and atopic dermatitis in 1). This conveys for a similar proportion between those with and without chromium allergy (26.27% vs 30.83%, p > 0.05). Likewise face dermatitis and leg ulcer/stasis dermatitis had no statistical difference between chromium positive and chromium negative patients (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of the MOAHLFA index between patients with a positive test to chromium and chromium negative test in the tested sample.

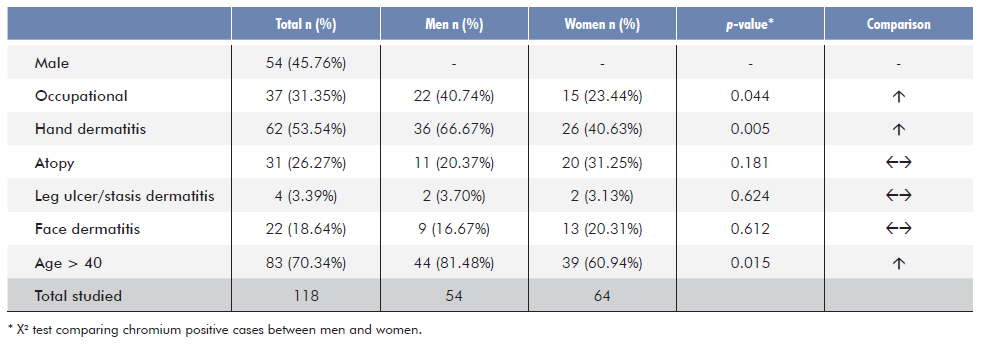

Table 3 shows the MOAHLFA index of all patients with chromium allergy stratified by gender. Occupational dermatitis was more fre-quent in men (40.74% vs 23.44%; p=0.044) and males also had more frequent hand dermatitis (66.67% vs 40.63%; p=0.005).

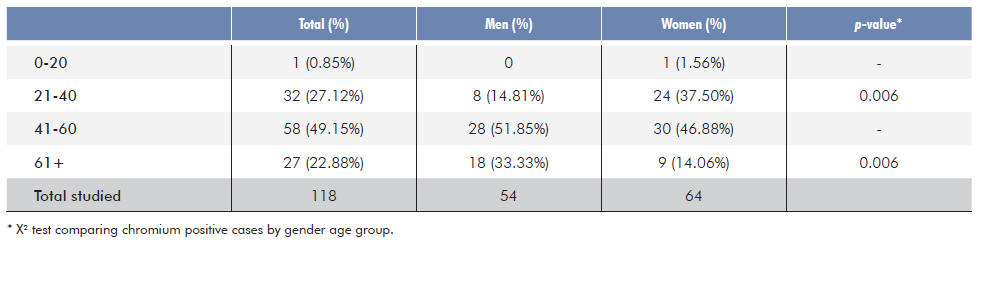

Regarding the distribution of cases by age and gender, the frequency was increased in the female gender in the 21-40 age group (37.50% vs 14.81%; p=0.006), but superior in men older than 60 (p=0.006). In the remaining age groups, we did not find significant differences (Table 4).

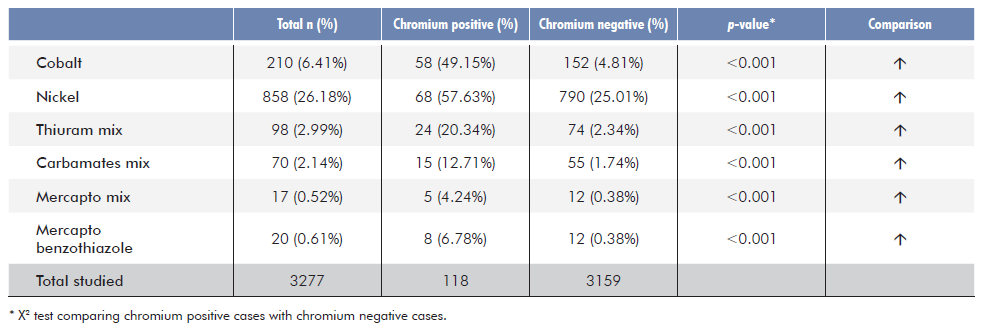

In this 10-year interval we also found 210 (6.41%) cases of cobalt allergy and 858 (26.18%) cases of nickel allergy. Ninety-eight (2.99%) patients were positive to thiuram mix, 70 (2.14%) to carba mix, 17 (0.52%) for mercapto mix and 20 (0.61%) for mercaptobenzothiazole.

In the subgroup of patients with chromium allergy, a concomitant positive patch test to cobalt occurred in 58 (49.15%), to nickel in 68 (57.63%), thiuram mix in 24 (20.34%), carba mix in 15 (12.71%), mercapto mix in 5 (4.24%) and mercaptobenzothiazole in 8 (6.78%). Simultaneous positive tests for chromium, cobalt and nickel were found in 41 (34.75%) patients.

In crude analysis, comparing chromium positive patients with chromium negative, concomitant presence of the allergens previously indicated was higher in the first group for every allergen studied (p<0.001) as shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Concomitant positive patch test reactions to other metals and rubber allergens in patients reacting to chromium versus non-reactive patients.

Seventy eight positive patch tests to chromium (66.10%) were considered to have current or past clinical relevance, with more than one possible source of the exposure in 55 cases. Contact with leather alone or concomitantly with other products, observed in 30 cases (25.42%) was the most frequent association.

Twenty-nine of the 118 (24.58%) cases were workers from the building industry and 16 (55.17%) reported regular exposure to cement and/or work gloves and/or shoes, 5 of whom only with contact with cement.

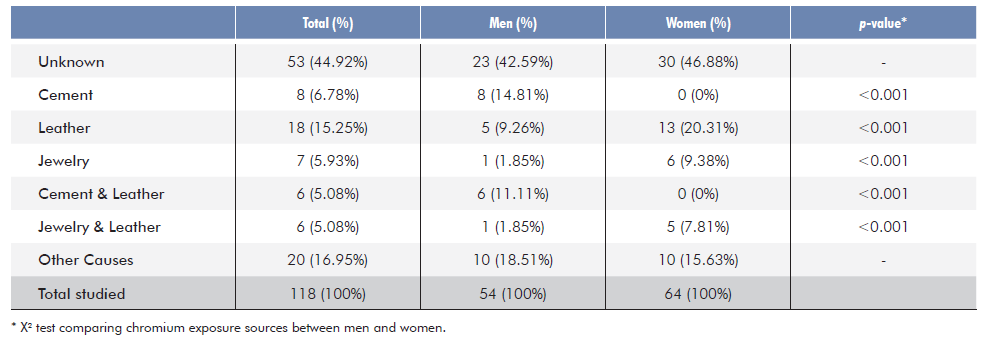

When distributing the sources of exposure by gender, we found that contact with cement or cement associated with leather (mostly work gloves) was more frequent in men. On the other hand, women were more frequently exposed to leather or leather concurrently with jewelry, or the latter as the single explainable source of exposure (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

The results show a high prevalence (3.60%) of chromium positive patch tests among the population studied for cutaneous hypersensitivity, with a high percentage of current or past relevant suggesting this metal allergen is still a frequent cause of ACD in Portugal, both in the occupational and non-occupational setting. In this population the percentage of positive patch tests is high but in in agreement with a previous study performed in the general population without dermatitis in the same region of Portugal in 2010 which showed a prevalence of positive PT to chromium of 1.3%, also with a higher prevalence in males (1.7%) compared to females (1.0%).19

A previous study from the same center performed between 1992 and 2011 in the population with cutaneous hypersensitivity found a higher prevalence of chromium allergy - 7%.12Although there is a 3-year overlap of data, the lower prevalence of chromium allergy is notorious in our study, especially when considering only the last seven years of the present study that do not overlap with the previous one (3.17% vs 7.0% p<0.001). Nevertheless, after 2010 we found no decreasing tendency in sensitization to chromium. In this period, the directive on the regulation of chromium in cement was already in force since 2005 (DIRECTIVE 2003/53/EC)17 and the legislation on leather, as we know it today, occurred in 2015 (Commission Regulation (UE) No 301/2014).17 As expected, the implementation of these measures will have an effect on sensitization only after several years as sensitization will be life-long and, consequently, patch tests will remain positive. Although some of our cases may have had a past relevant many of the workers from the building industry still have more hand dermatitis and aggravation in the occupational setting, namely with cement exposure. Nevertheless, concomitant use of leather gloves may be a confounding factor, because as the chromium directive on leather was later it may take more time to implement it locally. On the other hand, as our study found that occupational exposure was especially related with men over 60 years old, it may suggest these individuals were sensitized by cement in the past, before the implementation of EU directives.

Historically, allergy to this metal was closely related to exposu-re to cement in male construction workers, but studies from different European countries reveal that this allergy is becoming a consumer problem related to the use of skin products and leather and affecting more the female population,7 as shown in our studies were positive PT to chromium in females occur mostly outside the occupational setting.

From the occupational point of view, the main sources of exposure are related to the handling of products containing chromium and with individual equipment previously treated with this metal. We are then referring mainly to occupations that manipulate metals, use products such as cement or use individual equipment such as gloves or leather shoes. A frequent co-sensitization to rubber allergens from gloves and shoes, as shown in Table 4, corroborates this hypothesis.

Interestingly, we found only 23.73% of workers from the building industry, which is in line with other European studies. It should also be noted that another study from our center from 1992 to 2011 had found a percentage of 2.3% (123 cases out of 5250) of ACD related to chromium in the building industry, whereas we found only 0.88% (29 out of 3277), all males and with a medium age of 51.69 years.12 These findings suggest that the application of European Community directives in the regulation of chromium content in cement has been partially effective. It should be noted in Denmark, where chromium limitation in cement occurred long before 2000, a study from 2002 to 2017 did not record cases of ACD from exposure to cement.6 Concerning the EU directive on limitation of hexavalent chromium in leather there is still no evident effect, as we have mostly young females with chromium allergy and relation with non-occupational exposure, namely due to shoes. Moreover, frequent association with cobalt and nickel and relation to jewelry may suggest that this metal may also be present in less expen-sive jewelry after the EU directive limiting exposure to nickel.20

This study has limitations that are related to the retrospective nature and the sample of patients with complaints of dermatitis and who sought medical care. This study may represent an image of the current situation and predispose to a more elaborate study that can answer the doubts and hypotheses raised.

CONCLUSION

In our study, there has not been a significant decrease in sensitization to chromium over the years, but cases classically related to this allergy (cement in the building industry) are no longer the main cause of the problem. Therefore, this suggests that the focus of the problem is on chromium in leather.