INTRODUCTION

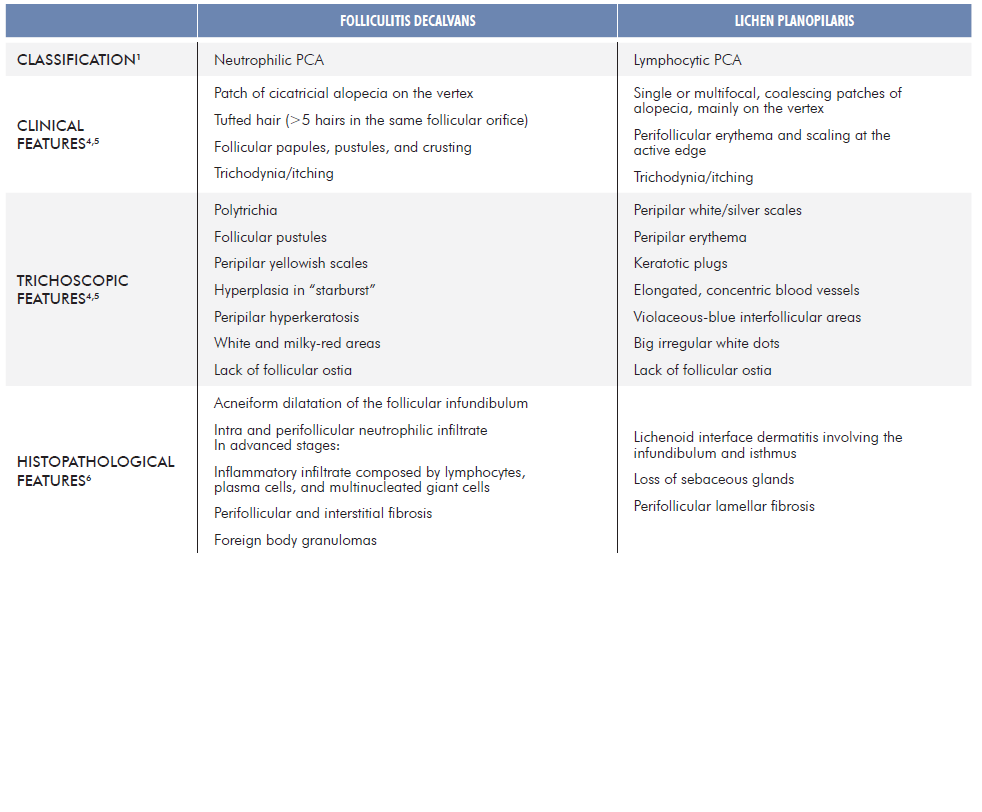

According to the North American Hair Research Society’s classification system, primary cicatricial alopecias (PCA) are classically classified by the predominant inflammatory cell infiltrate. Folliculitis decalvans (FD) and lichen planopilaris (LPP) have been recognized as distinct neutrophilic and lymphocytic PCA, respectively.1 However, there is new evidence suggesting that both clinical and histological aspects of these two entities can coexist in the same patient, either concomitantly or sequentially. Therefore, the existence of FD-LPP phenotypic spectrum has been proposed.2,3 Table 1 summarizes the classical characteristics of FD and LPP.4-6

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old man presented in our Hair Consultation due to pa-tchy alopecia localized on the vertex. The patient described alopecia with crusts and pustules at the onset of the disease, fourteen years ago. The diagnosis of FD was assumed, and the patient was treated with minocycline (200 mg/day) for 6 months with only discrete improvement. Consequently, treatment was changed to combination anti-biotic therapy with clindamycin (600 mg/day) and rifampicin (600 mg/day) for more than 6 months and the disease became stable without inflammatory activity. Maintenance therapy with minocycline was then adopted in a dosage of 100 mg/day for 16 months, and another 14 months with the same dose in alternate days. The disease stayed controlled for more than 10 years with no need for therapy.

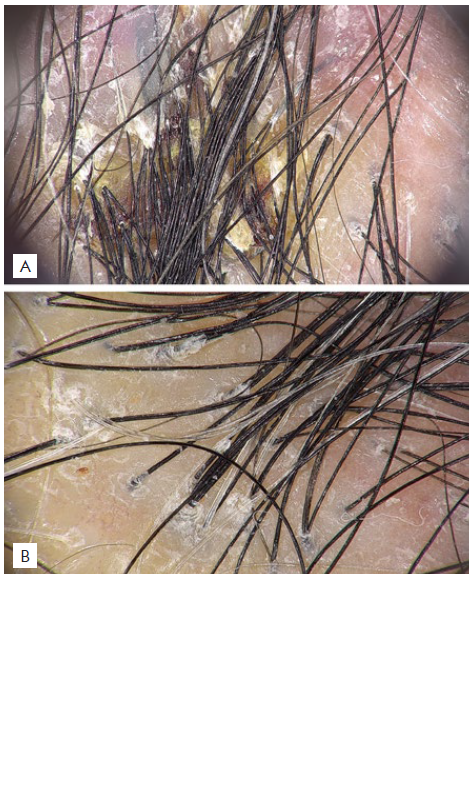

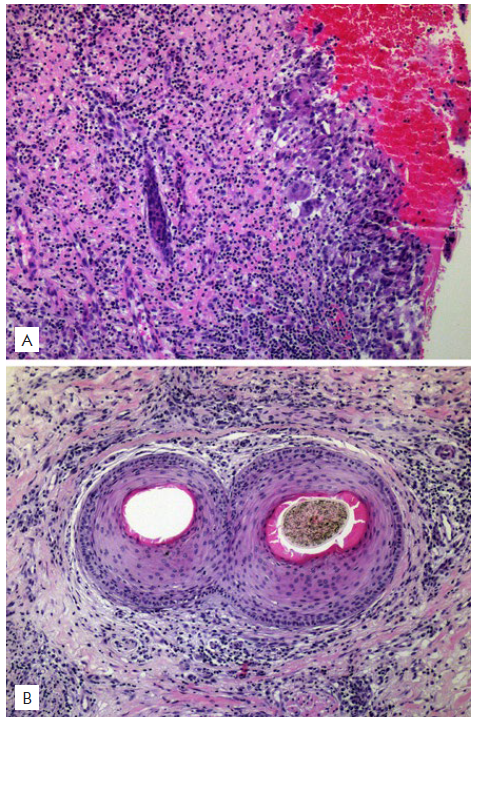

Recently, he complained of itch in previously involved areas of the scalp. Physical examination revealed patchy alopecia with diffuse erythema, perifollicular scaling and lack of follicular ostia (Fig. 1). Trichoscopy showed characteristics of both FD and LPP with polytrichia, red-milky areas, peripilar yellowish and silver scales, and peripilar casts (Fig. 2). Histopathological features were also consistent with both FD and LPP (Fig. 3). The patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg/day (works nicely in LPP), deflazacort 30 mg/day in weekend pulse and topical betamethasone ointment once daily. After two months an important improvement was achieved, with absence of peripilar activity (no casts, scales or inflammation). Deflazacort was reduced to 30 mg once weekly, doxycycline to 100 mg in alternate days and betamethasone ointment to twice a week. The disease remains controlled after 8 months with this therapeutic approach.

Figure 1 Area of alopecia with diffuse erythema, perifollicular scaling and lack of follicular ostia.

Figure 2 Trichoscopy: Polytrichia, peripilar yellowish scales, and red-milky areas characteristic of FD (A), and peripilar silver scale and casts, which are features of LPP (B).

Figure 3 Histopathological examination: A) Vertical section shows a dense, diffuse, granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate occupying the upper portion of the dermis and destroying hair follicles (x100, H&E). B) Horizontal section at the isthmus level shows two fused follicles in a compound goggle-like structure, surrounded by an intense, mixed, inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells (x100, H&E).

DISCUSSION

Similar to our case, other authors have recently described a clinical phenotype combining features of both FD and LPP.

Morais et al described a series of 13 patients diagnosed with “LPP with pustules”, based on the clinical presentation of perifollicular scaling, erythema, crusts, follicular tufts, and pustules. Curiously, lichenoid perifolliculitis was present only in seven patients, neutrophilic folliculitis in 10 and polytrichia in eight.7

In addition, Yip et al reported a series of 13 patients with clinical and histological features of both FD and LPP, either concomitantly, or sequentially. In sequential cases, there was an obvious shift from FD to LPP-like features. In the concomitant cases, typical clinical features of FD (tufting, pustules, and scarring alopecia) and LPP (perifollicular erythema, perifollicular scale, and scarring alopecia) were identified in different scalp locations. Interestingly, histopathological examination of scalp biopsies showed neutrophilic scarring alopecia in FD areas and lymphocytic inflammation with perifollicular fibrosis in concomitant or sequential LPP areas.2

More recently, Egger et al described seven patients with conco-mitant features of FD and LPP and a recalcitrant course, unrespon-sive to topical and systemic immunomodulatory/anti-inflammatory therapy. The most common clinical phenotype was hairless patches on the vertex with loss of follicular ostia and perifollicular scale, associated with the following findings: polytrichia, isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in the bacterial cultures of pustules and hemorrhagic crusts (over half of the cases); “mixed“ histopathological features, including multi-compound follicular structures of average 2-5 follicles (follicular packs), atrophy of follicular epithelium, lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with granulomas, prominent plasma cells, without neutrophilic infiltrate, and clinical improvement with adjuvant and systemic antimicrobial therapy.3

Pathophysiological mechanisms of both FD and LPP remain unclear.

Regarding FD, the isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in scalp lesions of this suppurative scarring folliculitis is almost universal. Therefore, the mainstay FD initial therapy includes antimicrobial treatment. Infection clearance usually corresponds to clinical improvement. Recurrence is frequent, thought to be due to the persistence of bacteria within the proximal hair shaft and the subepidermal region, which is responsible for maintaining a chronic inflammatory process, in genetically predisposed individuals.8 It is hypothesized that intense migration of neutrophils towards the perifollicular epidermis damages the follicular epithelium, exposing hair follicles’ antigens. In the final stages of FD, a lichenoid inflammation with fibrosis and complete destruction of the pilosebaceous unit may occur.8

LPP is considered a T-cell-mediated inflammatory phenomenon, which may be triggered by endogenous or exogenous stimuli, including microorganisms.9 In LPP, a Th1-predominant inflammatory cell infiltrate affects the bulge, an immunologically protected niche of the hair follicle epithelium, where epithelial hair follicle stem cells (eHFSC) reside.10 Hence, a bulge immune privilege collapse and an inflammation-induced eHFSC death seem to be fundamental components in the pathogenesis of LPP.10 Furthermore, a dysfunction of the PPAR-gamma peroxisome receptor has been shown in patients with LPP, which may be associated with the presence of self-antigens and subsequent lichenoid reaction.11 For this reason, anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory drugs are of outmost importance in the treatment of LPP.

Considering the existence of FD-LPP phenotypic spectrum, Yip et al theorize that a microbiome dysbiosis in the hair follicle may intensify the immune system response, exposing follicular neoantigens and promoting a chronic inflammatory response. Other possible explanations proposed by these authors are “koebnerization” of LPP into chronically inflamed FD areas and pre-existing unidenti-fied LPP predisposing to secondary bacterial infection.2Interestingly, Moreno-Arrones et al observed that patients with typical FD pattern presented statistically significant increased levels of S. aureus in affected hair follicles compared to patients with FD-LPP phenotypic spectrum.12 It is also possible that long term medication of FD plays a role in the lymphocytic transformation of an initially neutrophilic disease, mainly by changing the skin microbiota.2

In conclusion, although FD in a chronic stage or in remission may present with polytrichia and lack of neutrophils, some patients seem to show clinical, trichoscopic, and histological findings similar to LPP over time, which raises the question: are they two distinct entities or can they be a part of a continuous phenotypic spectrum? It is important to recognize the possibility of this phenotypic spectrum to optimize clinical management, which may require a combination of anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory agents and systemic antibiotics, depending on the phase of the pathological course.