INTRODUCTION

Purpura fulminans is a clinical emergency characterized by cutaneous necrosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thrombotic occlusion of small and medium-sized blood vessels may lead rapidly to multi-organ failure. Immediate treatment is required to prevent mortality and long-lasting morbidity.

The case described illustrates a presentation of purpura fulminans in an young adult patient with an hereditary partial protein C deficiency prompted by a minor previous infectious episode (tonsillitis). Both factors contributed simultaneously and synergistically, triggering the clinical picture. This case emphasizes the importance to bear in mind that purpura fulminans can have multiple causes and may occur in a variety of clinical scenarios - sepsis being the better known, albeit, not the only one. In rare situations, it may occur as an autoimmune response to otherwise benign infections (post-infectious purpura fulminans).

CASE REPORT

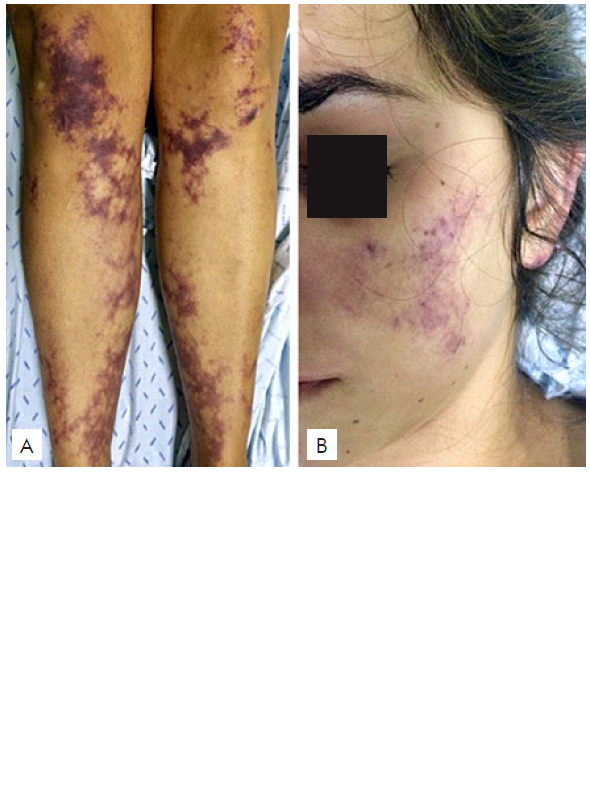

A previously healthy 20-year-old female presented with retiform purpuric lesions located in the upper and lower limbs, ears, and malar regions bilaterally (Fig. 1). These lesions were painful, had 24-hours of evolution and were rapidly progressive. Within hours, they became confluent, with formation of large necrotic violaceous plaques, that occupied almost the entire right lower limb (Fig. 2). At admittance, the patient had no fever and no accompanying symptoms. She was hemodynamically stable and otherwise well.

Figure 1 Initial clinical findings. (A), Reticulated violaceus patches located at the lower limbs. (B), Violaceus lesions of the face, at the malar region.

She reported having had a sore throat and fever, a week before, that subsided with antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid). She denied chronic medications besides oral contraception for several years.

Laboratory test results on admittance showed a normal complete blood count, with elevated d-dimers (21.68, N < 0.60 ug/mL), but no alterations on the chemistry panel or coagulation tests (both prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time were normal). Inflammatory laboratory parameters were low or negative, including C-reactive protein and procalcitonin. The search for occult septic foci was negative. Antistreptolysin O titre and antinuclear anti-bodies were negative.

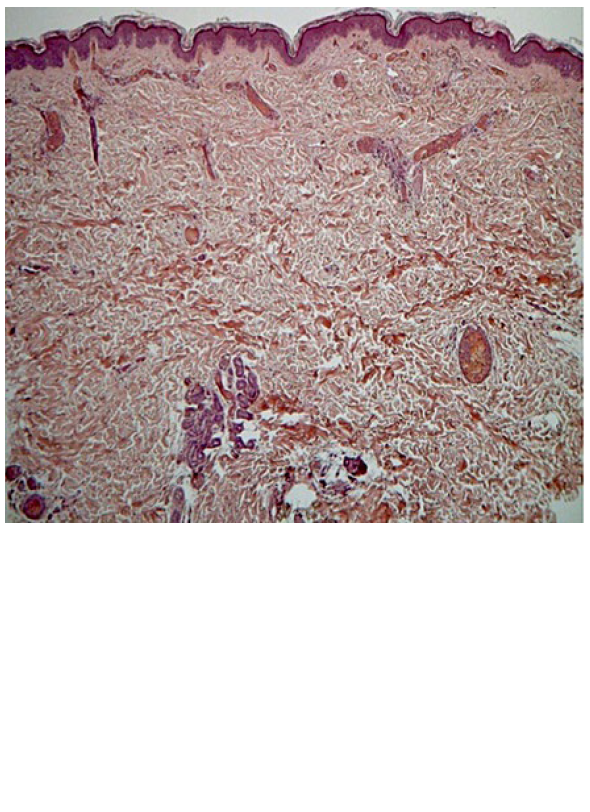

Additionally, skin biopsy revealed thrombotic occlusion of the dermal vessels, without associated inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Histological findings, revealing thrombotic occlusion of the dermal vessels, without associated inflammatory infiltrate.

In light of the described findings at admittance - purpura fulmi-nans of unknown etiology with rapid progression - the patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics (meropenem), anticoagulation with enoxaparin (80 mg twice daily) and systemic corticosteroids (1 g metilprednisolone EV for 3 days with subsequent tapering).4

Only days later, did the patient mention that in her family a direct cousin had suffered a leg amputation as a newborn, because of a “blood clotting problem”. Further genetic study revealed a heterozygous protein C mutation (exon 9, c.1332G> C, p.Trp444Cys), resulting in a partial protein C deficiency (functional protein C of 65%).

The remaining prothrombotic study revealed no other findings (including antiphospholipid antibodies, factor V of Leiden, homocysteine and cryoglobulins). Unfortunately, dosing of autoantibodies against protein S was unavailable and, therefore, not performed.

With the aforementioned treatment, progression of purpura and skin necrosis stopped. The patient required prolonged local care with dressings but overall had a favorable clinical evolution, with complete recovery after six months. After 8 months, enoxaparin was replaced by warfarin, that she keeps until today (target INR range 2.0 - 3.0). Three-years after these events she remains well, with no further thrombotic events.

DISCUSSION

Purpura fulminans is a rare clinical emergency that occurs in a context of disseminated intravascular coagulation as a result of increa-sed expression of procoagulant factors associated with the depletion of natural anticoagulants. It should be noted, however, that purpura fulminans is not an independent entity, and may occur in a multiplicity of clinical scenarios (more commonly induced by sepsis or by warfarin treatment, but also associated with inherited protein C deficits). Mortality and morbidity in the setting of purpura fulminans are high, commonly leading to limb amputations. Prompt diagnosis and readily treatment are crucial.

Protein C is a vitamin K-dependent serine protease that constitutes a major natural anticoagulant. Protein C deficits can be acquired, namely due to consumption during sepsis or during the onset of warfarin, in this case due to a transient imbalance between protein C and pro-coagulant factors that are synthesized with different timelines under the dependence the same cofactor, vitamin K. Inherited homozygous mutations or compound heterozygous mutations represent a rare cause of protein C deficiency, which usually presents in the neonatal period, leading to limb amputations, as occurred in this patients’ cousin, or to death if left untreated.1,2On the other hand, heterozygous mutations lead only to partial deficiencies, that alone are not associated with cli-nical manifestations. Thus, in this particular case, other causative factors must be implicated, namely the infectious episode reported 7 days earlier. This is noteworthy because in post-infectious purpura fulminans the serum concentration of protein S may decrease after an infectious event due to the production of antibodies during the infection that can bind and inhibit protein S function,3 but unhappily this test was not available among us and serum values of protein S showed no significant change during the course of the disease.

Post-infectious purpura fulminans is rare and develops during the recovery period from group A streptococcal infection, varicella-zoster, or rarely, from human herpesvirus 6 infection.3,4

Postinfectious purpura fulminans begins 7 to 10 days after the onset of the initial infection and correlates with the production of infection-triggered antibodies to protein S.4,5As protein S is a co-factor of protein C during anti-coagulation this could explain the exuberance of the clinical findings in a patient with a partial protein C deficiency.

This case draws attention to purpura fulminans, a rare clinical emergency which requires immediate treatment to prevent mortality and long-lasting morbidity. Although sepsis is the most frequent etiology, it is important to bear in mind other rarer causes. In addition, the case stands out for its rarity and striking presentation.