Introduction

In a context of increasing urbanisation and the continuation of the relentless expansion of human settlement and land take (World Bank, 2018), there has been a move towards a greater reflection on how territorial and local planning is written and implemented (Albrechts, 2006; Allmendinger, 2017, Faludi & van der Valk, 1994; Healey, 1997; 2004; Mintzberg, 2002). Within the planning system, opportunities for future generations to benefit from the historic environment have been underexplored and underappreciated (Stubbs, 2004; Pereira Roders & van Oers, 2014). Moving beyond the nineteenth-century drive for monumentalising the past (Choay, 1992), it has become clear that for the historic environment to survive it must be flexibly adapted to the needs of today’s generations without undermining the value and significance of heritage assets. The task of planning in the twenty-first century, then, should be process focused in ensuring a balanced approach to bringing abandoned “Historic Centres” back to life whilst ensuring that developments conserve and even enhance the overall significance of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL). This paper examines the challenges of sustainable urban planning in a Portuguese context, with specific reference to the Mouraria neighbourhood in the Historic Centre of Santarém, proposing a values-based approach to conserving and enhancing heritage as a valuable resource for sustainable development.

The paper proposes that historic centres of settlements are imbued with special meaning and significance and that their pronounced decline can be reversed in such a way as to enable the re-establishment of balanced communities. This is based on an integrated approach to planning and conservation policy, permissible under existing national legislation, and very much in keeping with European spatial planning theory and practice. Whilst other routes could exist, the paper proposes that the HUL approach is most compatible with recent planning and geographic theory and that, tailored to local contexts, it can provide a resource-efficient and collaborative pathway to the delivery of effective and bottom-up policy. It is certainly preferable to the current inertia in the local management of many historic environments. The focus of the empirical component of this paper is at the evidence-gathering stage of policy production as a grounded bottom-up critical exercise, to demonstrate how HUL approach principles could make this more reliable, robust and democratic. Such an approach is in line with the move in national and EU planning policy away from a regulatory and towards a process-led approach to the built environment.

own elaboration, based on Google Earth cartography

Note: Source: Figure 1: The Mouraria (outlined in yellow) in the context of the wider city of Santarém

The paper comprises three main components. The first introduces Santarém, a historic mid-level administrative urban centre, and outlines the current policy and heritage conservation context in urban governance in Portugal, with specific reference to Santarém as a case in point. The second looks at what is involved in the HUL approach, outlining its key concepts and tools, and considers what evidence and processes would be involved in implementing this in Santarém through a worked example. Finally, some recommendations on the application of the HUL approach, supporting evidence-based policy production, monitoring and management of the historic environment, are discussed as outcomes of the empirical work.

Santarém: a Portuguese “anyplace”

Santarém, sitting atop a cliff with commanding views over the Tagus valley, has an ancient and multi-layered history and has, periodically, invested technical and financial resources in the rehabilitation of its Historic Centre. However, as in many cities in Portugal, the challenges of population decline and an aging residual resident population have undermined social cohesion and economic vitality (see Table 1), and the material fabric is visibly deteriorated.

Table 1: Demographic picture of Santarém

| 2010 | 2018 | |||

| Santarém | Portugal | Santarém | Portugal | |

| Resident Population | 62,453 | 10,573,100 | 57,611 | 10,283,822 |

| Population Density Median nº individuals per km2 | 111.5 | 114.7 | 104.3 | 111.5 |

| Aging Index Elderly per 100 young people | 154 | 122 | 189 | 157 |

| Foreign Population as a % of the resident population | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 4.6 |

| Births | 575 | 101,381 | 452 | 87,020 |

| Deaths | 816 | 105,954 | 767 | 113,051 |

| Natural Increase | - 241 | - 4,573 | - 315 | - 26,031 |

| Classic Family Dwellings | 35,026 | 5,852,186 | 35,417 | 5,954,548 |

| New building completions for family habitation | 102 | 17,445 | 34 | 7,309 |

| Average bank valuation of accommodation (€/m2) | 1,040.0 | 1,223.0 | 941.0 | 1,192.0 |

Source: PORDATA, 2019

The twentieth century in Santarém was marked by explosive development beyond its medieval walls, leading to the creation of new functional programmes and a wave of interventions to respond to this expansion. The biggest impact came in the middle of the twentieth century through the adoption of the first General Development Plan in 1947 (Anteplano Geral de Urbanização de Santarém) by João António de Aguiar, planning for the expansive suburbanisation of the city along functional rationalist principles. The expanded scale of the new city meant that transport was required to get from one side to the other, and commercial services would therefore do better to locate themselves in areas of greatest accessibility to the motor vehicle, outside of the narrow routeways through the Historic Centre. Aguiar’s Plan, given the substantial difficulties in its implementation, was reviewed twice, in 1958 and in 1961, and was replaced in 1978 by the second General Development Plan (Plano Geral de Urbanização de Santarém) by Tomás Taveira. While the Plan sought to raise the visibility and living conditions of the Historic Centre, it also continued the outward expansion of the city through polynucleated growth points in the suburbs and satellite settlements (CMS, 1978, p.21).

The whole Historic Centre is designated in local planning policy as heritage for safeguarding purposes, and the city even made an application for UNESCO World Heritage listing in 1998 based on its unique claim to having examples of architecture from all phases of the gothic period. It is considered, therefore, that the area has heritage value and significance; however, the application did not succeed. UNESCO informed the Portuguese state that the candidacy would not be selected, leading to retributions between local and national levels of government (Peixoto, 2002). Since then, the municipal election of 2001 led to a radical change of direction for the Municipal Council away from concerns relating to heritage.

A paradox exists in that on the one hand the Historic Centre is recognised in theory, at least at the level of its monuments, as worthy of conservation and of universal value, and this is reflected to some extent in its planning documents. On the other hand, there has been no systematic action to safeguard this area in practice, reflecting a lack of motivation or holistic vision. The area is therefore caught in a no-man’s-land of slow decay without real vision or action for its regeneration or its definitive abandonment.

Heritage conservation in the context of Portuguese planning law and legislation

In Portugal, the continued and sustained decline of historic cities is a subject of great debate (Campos & Ferrão, 2015; Gonçalves, 2018; Oliveira, 2011; Santos, 2018) and, rather than leaving these areas to decline indefinitely, at a national legislative level the launch of the Legal Statute for Urban Rehabilitation (Regime Jurídico de Reabilitação Urbana, RJRU) in 2009 was a response to the degradation of Historic Centres, representing a shift in perspective, encouraging residents and investors via tax incentives to engage in urban rehabilitation, and moving away from legalistic responses. Crucially in terms of sustainable development, within the RJRU older parts of the city came to be seen as heritage ensembles: resources that need to be conserved and enhanced, not only for their heritage values, but for a wider set of values based across social, economic, and environmental indicators to be implemented and delivered in a more transparent and inclusive way (Santos, 2018).

A commitment by the Portuguese state to the principles of sustainable development has been made internationally, recently through Habitat III in 2016 and the new urban agenda in which a commitment to sustainable development must be put into practice, addressing problems emerging from dispersed and fragmented populations, and the poor spatial interface between populations and services. Furthermore, ongoing commitment to the EU’s spatial planning principles, which encourage a process- rather than an object-led focus to territorial management, has been given increased vigour in the renewed National Programme for Territorial Planning Policy (Programa Nacional da Política de Ordenamento do Território, PNPOT, 2020) and through the continued importance of Regional Spatial Strategies (Planos Regionais de Ordenamento de Território, PROT). It is at municipal level that this process has yet to catch up. The “first generation” Local Plans (Planos Directores Municipais, PDMs), produced in the 1990s and focusing in a regulatory manner solely on the physical built environment, are all due to have been replaced by now to be aligned with the more holistic approach of national and regional spatial planning (Gonçalves, 2018). However, a high proportion of municipalities have yet to update these. In 2017, 77 percent of PDMs in the Lisbon and Tagus Valley Area were more than ten years old, and 59 percent (31 PDMs) were over 20 years old, including that of Santarém (CCDR-LVT, 2017: 227).

The need to update local policy, away from purely regulatory epistemologies of the past, and towards a spatial planning focus on process-led policy is legally mandated yet has not been achieved. Furthermore, through the RJRU, the planning system became arguably the primary vehicle through which integrated cultural heritage management can be achieved. Within heritage management theory, the shift to the idea of cultural heritage management has in the past primarily focused on the protection of specific monuments and areas designated as cultural heritage (Smith, 2006; Fairclough et al., 2008). A qualitative shift has emerged in heritage principles and approaches, so that the focus is not on conservation at all costs, but on changes managed rather than prevented, particularly in relation to communities and their future sustainability (Veldpaus & Pereira Roders, 2014). Beyond a focus solely on the protection of tangible built heritage assets, integrated approaches to heritage broaden the concept of conservation to include intangible assets, and aims to reconcile protection and conservation with development and vitality (Jokilehto, 2007). As noted by Fredheim & Khalaf (2016: 473), “conservation should be regarded as a process concerned with preserving and enhancing qualities of heritage, or aspects of value. In so doing, conservation can facilitate the use of, and drawing of benefits from, heritage in the present and future”. To this end, heritage is an important resource to be conserved and enhanced within the scope of sustainable development. Planning for this is more effective when it engages with processes rather than seeking to regulate individual objects, through the prism of “management” rather than “regulation”.

Attempts to systematise this into a standardised process overlooks the fact that different forces and processes are at play in different urban contexts. An inclusive and efficient way to understand these specific dynamics is to take a bottom-up, grounded approach which does not assume a priori values but does at the same time triangulate expert, administrative and local knowledge in a critical information analysis exercise.

Sustainable Development envisaged through a values-driven HUL approach: conceptual and methodological issues

Sustainable urbanisation brings a need to manage heritage in a constantly-changing context and to integrate older urban areas into a multipolar, multidimensional and multi-scale city. Central to a process of integrated management of urban areas, including heritage, is the understanding of the city based on a system of intersecting values. As Pye (2001, p.57) proposes, it is “the meanings and values attached to objects... [that] provide the very reason for conservation”. The value societies place on heritage assets, at least in theory, has a positive correlation with the assets’ survival; so much so that whilst sometimes dismissed as ‘relativistic’, actually “value has always been the reason underlying heritage conservation” (de la Torre, 2002, p. 3). In understanding values, one can build up an overall picture of the relative significance of heritage assets (Manders et al., 2012).

The conservation of urban heritage, included within the concept of sustainable urban development, is based on the management of these values, and in doing so safeguarding the identity and significance of the place, enabling current communities to meet their needs within this urban space. Change within an area is inevitable and often beneficial, and in Santarém, urgent change is required if the wholescale disintegration of the urban fabric is to be prevented. The focus of the practical component of this paper is the evidence-gathering stage of policy production, to demonstrate how HUL approach principles could make this more reliable, robust and democratic.

The HUL approach comprises a “comprehensive and integrated approach for the identification, assessment, conservation and management of historic urban landscapes within an overall sustainable development framework” (UNESCO, 2011: 3). This is the most recent articulation of a move within heritage studies that seeks to balance sustainable development with conservation of heritage value and significance, whilst at the same time being more aligned with European spatial planning principles (Allmendinger, 2017, Faludi & van der Valk, 1994; Healey, 1997; 2004; Graham and Healey, 1999; Mintzberg, 2002; Veldpaus and Bokhove, 2019), as opposed to the rigidly structural Australian concept of spatial planning (Taylor and Saxena, 2019).

Some researchers, in an effort to simplify and standardise the HUL approach for the benefit of the professionalised yet time-scarce bureaucratic systems of certain developed nations, have proposed standardised processes for implementing the HUL approach (Gutscoven, 2016; Veldpaus, 2015; Veldpaus & Pereira Roders, 2014). However, the opportunity embedded within the approach is not to be formulaic in this way, but to promote a sufficiently flexible and transferrable tool that is responsive and attentive to different administrative arrangements and socio-economic contexts. Indeed, as Sadowski (2017) highlights, the flexibility of this approach means that it has been implemented successfully across all continents, without the need for taxonomic regularisation. The approach focuses critical attention on recognising each layer of information that contributes to the city and the fact that the city is not limited to its historic centre (UNESCO, 2011) and its monuments, but encompasses the whole organic system in which historical significance is bestowed and perpetuated. Conceptually it is broad enough to respond easily, efficiently and effectively to the open door provided by Portuguese planning and conservation legislation and guidance, as well as broader currents in European spatial planning, particularly in terms of sustainability and civic participation.

The conceptual model through which the value and significance of the HUL is identified requires both desk-based analysis (principally in the management context assessment phase) and fieldwork in its physical condition and cultural value and significance assessment phases). Given the size of the relatively large area of the Historic Centre of Santarém, at 68 hectares, (CMS, 2015), a result of the city’s more salubrious past, the Mouraria was chosen as a case study subject partly due to its ongoing marginality but also given that this area was one of the few neighbourhoods to have been the subject of a previous Safeguarding Plan (Plano de Pormenor de Salvaguarda da Mouraria) in 1994. This plan did not stem the pace of decline but did draw attention to the fact that the repair of the built environment is inherently linked to the policy context and social and economic dynamics of the neighbourhood, and to the wider city.

Within the municipal planning function, planning policies set the framework under which decisions on planning applications are made. In general terms, they should set out what development can happen, where, and how much there can be (quantum), so that sustainable development - or, the balance between economic, social, environmental and cultural interests - is achieved. However, my analysis here takes the view that adopted plans do not comprise a set of rational and coherent interventions that respond to ‘real’ territorial problems. Furthermore, the epistemological stance taken here is that concepts of sustainable and balanced development are situated/contextually dependent, multiple and can be internally inconsistent (Fischer, 1995; Yanow, 2000; van Bommel et al., 2015). Such an approach has clear compatibility with developments in critical heritage studies (Smith, 2006) and the challenge laid down to democratise heritage discourse.

Grounded analysis of all regional and local level planning policy documents identified ten locally relevant value categories currently at play in territorial, urban and heritage management, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Santarém, historic and urban values definitions

| Value | Definition |

|---|---|

| Aesthetic | The ways in which people can draw sensory, emotional and intellectual stimulation from the place. This could involve historic, stylistic or artistic movements; concepts related to an important event in the past; or engagement with landscape and setting. |

| Amenity and Use | Whether people can/do use a place in safety, comfort and free from negative externalities. Use value is a key determinant in an asset’s survival. |

| Social, Community and Cohesion | Quality of social interaction in space, including the meanings and collective associations people have that are situated in this space and which contribute to a sense of place. |

| Material | An original result of human labour or craftsmanship; technical or traditional skills and/or connected materials; integral materialisation or knowledge of conceptual intentions. |

| Mobility | The ability for people to penetrate and navigate the area with ease, and to access those essential daily services required to achieve a standard quality of life. |

| Economic and Commercial | The function and utility of a space, whether redundant, original, or attributed; the option to use it and/or retain value for future generations; the role it might have (had) for market or industry; property value. |

| Associative | The illustrative or associative ways in which people engage with space. Spiritual, beliefs, myths, religions, legends, stories, testimonials of past generations; collective and/or personal memory or experience; cultural identity; anthropological/ethnological value. |

| Scientific and Evidential | The potential of a place to yield evidence about past human activity. And, importantly, the ability of current populations to engage with this directly, without the need for gatekeepers. |

| Environmental and Hydrological | The relationship between the building and its environment (natural/man-made); identification of ecological concepts in practices, design, and construction; manufactured resources reused, reprocessed, or recycled. Presence, impact, interaction with and integration of water resources. |

| Governmental and Political | Evidence of proactive public sector presence in an area, responsivity and effective management and oversight (governmentality). Educational role for political targets (e.g. founding myths; glorification of leaders). |

Source: own elaboration.

These categories were built up and refined over the course of the study period, between June and December 2019, using grounded and ethnographic methods. A broad toolbox of techniques was implemented in the study site during the six-month project, including the collection of fieldnotes; individual interviews; a focus group; self-completion surveys; three walking tours; and documentary analysis of planning policy. Through grounded analysis, the coding of data is an ongoing, dynamic and fluid process, passing through open, axial and selective coding stages (Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Charmaz, 2006), and navigating the technical narratives within the heritage field, official voices within regional and local planning policy, along with locally situated voices. Emergent categories were drawn out at each stage of the process, sense-checked against disciplinary precedent, and triangulated through piloting their practical application in place.

Value categories give the greatest attention in current adopted planning policy encompass a range of economic, social, environmental and cultural indicators, but they are not treated equally. There is a clear sense in which decision-makers are encouraged to give precedence to Aesthetic, Amenity, Mobility and Associative values, in broad terms. The others, while playing their (often statutorily mandated) role, are more passively treated and, in the case of Environmental and Hydrological value, miss important opportunities since there is scant if any treatment of urban ecology or sustainable drainage systems.

As mentioned, the continued delay in adoption of a PDM that is strategic and process-led, rather than regulatory, for Santarém is a hindrance to effective integrated urban rehabilitation. There are notable gaps in existing plans in relation particularly to social inclusion and cohesion, environmental and economic values and indicators which prejudice the Municipal Council’s ability to deliver sustainable regeneration of the historic environment.

Managing Significance

Having established the context for urban and heritage management, the remaining tasks in building a solid evidence base for an integrated plan are the physical condition assessment, and the distilling of the value and significance of the area(s). Sustainable development in general terms in a HUL is a process concerned with conserving and/or enhancing aspects of value and, in the case of heritage, its overall significance. If values provide the reason and motivation for conservation, then those assets and locations demonstrating greater significance across a range of value types are logically the most valuable. In practice, though, integrated urban rehabilitation’s object is not the individual monument, but the city as a whole.

Addressing the integration of the HUL in a sustainable manner requires an evidenced understanding of the significance of the space, and those values that act and interact to achieve this. This evidence can enable decision-makers in various public functions to assess more effectively the impact of a development and/or intervention on the HUL through its potential to reduce or enhance its overall significance. Such an approach has been promoted on a practical level by Historic England (2008; 2019) and others (Buckley et al., 2015; Colavitti & Usai, 2019), suggesting several features of the historic environment that should form part of a more textured analysis of the HUL. As a result, I was able to develop an Environment Condition Survey, refined and tailored to the context of Santarém, and which I piloted in the Mouraria during October 2019.

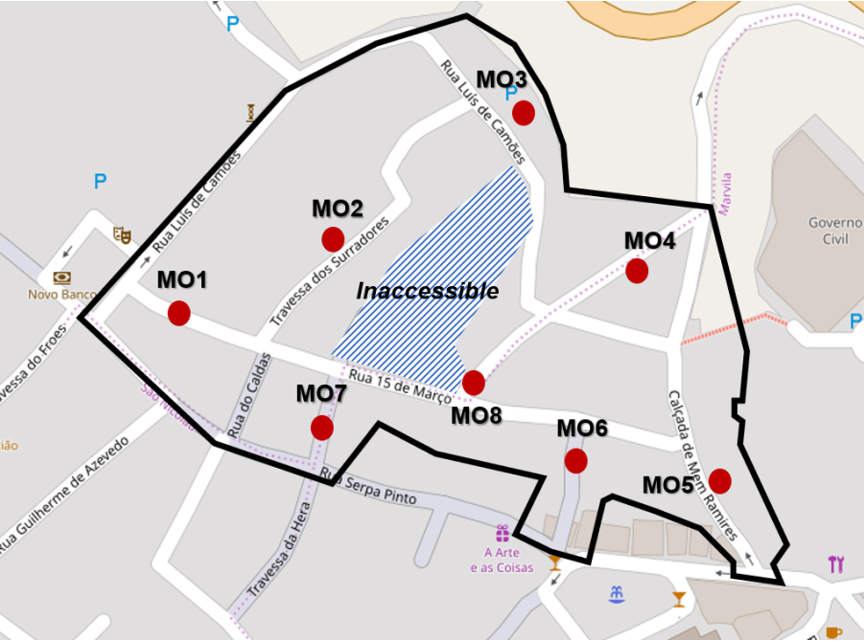

The survey was designed to enable clear and concise identification of features present in the neighbourhood, inviting explanation as to how these contribute to or detract from its character, and ultimately to determine the extent to which individual locations demonstrate those values sought or said to exist. Surveys were carried out at eight locations within the Mouraria, as shown on the map in Figure 2, having first been piloted to ensure that accounted to as many layers of the urban experience as possible while correlating with the value categories distilled in the previous section. Surveys were conducted with the collaboration of three groups on different occasions, comprising respectively the public sector; local residents; and visitors to the city. Self-completion instructions were provided, and during the process these groups proposed additional/alternative categories more relevant to the neighbourhood. The sections comprised the following: 1) Initial Reaction; 2) Spaces; 3) Buildings; 4) Views; 5) Landscape; 6) Ambience; 7) Values; and 8) Significance and the Spirit of Place.

own elaboration, based on Bing cartography.

Source: Figure 2: Map showing Condition Survey locations within the Mouraria

In analysing the data in the survey, a textual picture of the neighbourhood emerged which was transposed into a condition rating against each value category, crudely classified into negative, neutral or positive condition (Table 3). By aggregating the results, we see that the Mouraria as a whole is currently an area of negative value, subject to continued physical, social and political isolation from the remainder of the centre which it adjoins, which is not sustainable. However, disaggregating the results by value category, local strengths become evident. There is particularly strong associative value, much of which is related to high material value, ironically given that the built environment has not undergone significant intensive alteration due to neglect rather than design. The area also benefits from reasonable scientific and evidential value, with local people having engaged with the place and being able to find solutions to problems that they know the Municipal Council is unable or unwilling to resolve.

Moderate results for social and cohesion values stem mainly from the strong sense of community in the western part of the Mouraria, and the diverse residual communities entrenched in the eastern areas. There is evidence that these communities are highly vulnerable, but their persistence in a space of low amenity or governmental value is admirable. Environmental value in the area stems from its privileged location, only fully experienced at its northern extremity, overlooking the area non aedificandi of the Gaião valley, and with long views across the Tagus valley, with shorter views to the monumental Sá de Bandeira School and Santa Clara Convent. Water, which if well managed would be of positive benefit, is a liability in this area given the amount of façade exfoliation and ingress during rain. Combined with the high-water table and problems associated with it, this invites the need for an integrated model of water flows and/or a water cycle study to inform future policy.

Table 3: Condition per value type of each survey location

| MO1 | MO2 | MO3 | MO4 | MO5 | MO6 | MO7 | MO8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aesthetic | ||||||||

| Amenity & Use | ||||||||

| Social, Community & Cohesion | ||||||||

| Material | ||||||||

| Mobility | ||||||||

| Economic & Commercial | ||||||||

| Associative | ||||||||

| Environmental & Hydrological | ||||||||

| Scientific & Evidential | ||||||||

| Governmental & Political |

(Green = positive; Amber = neutral; Red = negative)

Source: own elaboration.

A new approach should recognise the city-wide processes involved in creating and perpetuating this neighbourhood’s reputation as a low-income ghetto with a rapidly crumbling building stock, identifying and addressing these processes through what should be a social process of plan making (Healey, 1997). In other words, this neighbourhood is not unsustainable because the rest of the city is sustainable; rather unsustainability in the Mouraria is indicative of unsustainable urban management practices across Santarém’s municipal area.

The results of the survey drew out a textualised characterisation of the neighbourhood, not only drawing attention to tangible attributes, but also intangible features. The results enabled the main characteristics and challenges of the neighbourhood to be identified thematically. The main characteristics of each zone are described in Table 4, which provides a baseline summary, drawn from survey results, of the current condition of each value indicator.

Table 4: Condition of value categories in the neighbourhood

| Value | Characteristics in the Mouraria |

|---|---|

| Aesthetic | Cohesive historic environment with a feeling of authenticity and unity of design and palettes. Excellent views of beyond the area to cultural and natural heritage. Visual decay and degradation to the built environment. Modern development not entirely successful and often obtrusive. |

| Amenity & Use | In the western part, good levels of occupation and use, with a mix of residence tenures. Private efforts to improve and soften spaces. Further east, low levels of use and feelings of insecurity because of the highly degraded built environment, with strong negative externalities impact on desirability and use. |

| Social, Community & Cohesion | There are strong interpersonal relations and evidence of community integration and support. The area suffers from little formalised space to facilitate this. This zone is important to diverse marginalised groups and remnant communities, but there is low cohesion value. |

| Material | In the western part, the built environment contains high interest and variation in materials, and evidence of attention to detail in some recent restorations. However, there is also widespread use of incompatible materials resulting in further physical and visual decline. In the central part of the neighbourhood, high attrition of historic structures has occurred as collateral damage as a result of deep excavation. |

| Mobility | Public routeways provide challenging terrain for pedestrians. There is unrealised potential for connectivity to the Ribeira, but the zone presents a hostile environment for all road users given the poor condition, instability, and narrowness of the public highway. |

| Economic & Commercial | There is generally low commercial and economic interest in the zone, with a proliferation of long-term unsold or unlet dwellings. Conversely, there is high interest in investment opportunities, and clear potential to benefit from expanded commercial activities from the adjacent main shopping areas. |

| Associative | High value associated with the zone being ground zero of the reconquest of Santarém in 1147 and its resultant role in national history and identity, as promoted during the romantic era (Herculano, 1846). Remaining mercantile dwellings serve as remnants of functional relationship between this area and the Ribeira neighbourhood. Archive photographs reveal an area almost unchanged during the twentieth century. |

| Environmental & Hydrological | High environmental value as an urban-rural interface. High hydrological value given high number of cisterns and high level of groundwater. However, the lack of environmental management lowers this value, a result of the negative impacts of uncontrolled groundwater upwelling caused by misadventure, and widespread fly-tipping. |

| Scientific & Evidential | High archaeological potential, and various items/monuments of interest. High known and untapped archaeological value, but conversely low capacity for local people to engage with this. Degraded but still present ancient street pattern. |

| Governmental & Political | Little evidence of political interest or regard. Local monuments and publicly owned dwellings the most compromised. Highly politicised, with the zone viewed as marginal backland, the recipient of negative externalities. Notably inferior public provision in this zone, and little political receptivity to local claims. |

Source: own elaboration.

While recognising that each neighbourhood in the historic centre of Santarém is likely to demonstrate different manifestations of structural problems, which will be mediated through differing neighbourhood dynamics, ultimately this evidence will enable policymakers to trace the roots of current problems back to issues that can be addressed through a wider strategy.

The western part of the neighbourhood seems to be reasonably sustainable and appealing to the private sector for its rehabilitation. However, the risk is that the social balance is indirectly disturbed through rapid change and potential gentrification. This does not appear to be imminent, although the poor evidential values even in recent developments - lack of input from local people in providing testimony and knowledge about the site as part of the decision-making process - are a risk for ‘authenticity’.

The central part of the neighbourhood appears to be a cautionary tale in the importance of an integrated plan for the historic environment, respecting its environment and setting. It is widely acknowledged that Santarém’s slopes are problematic, and since 2014 the multi-million Euro Stabilisation of Santarém’s Slopes Project (Estabilização das Encostas de Santarém) has been ongoing. At the same time, though, the city has been occupied for millennia, and those same buildings that were recently demolished to make way for a three-storey subterranean car park had stood for several centuries and had declined mainly through a lack of conservation. The excavated ground quickly filled with groundwater and, as a result, the project was abandoned, leaving a fetid swamp, literal and thereafter symbolic, at the heart of the neighbourhood. The privileging of private vehicular mobility and of modern materials over other values has damaged the HUL of the neighbourhood particularly acutely, not only depriving future generations of material and evidential insights in the place, but also having wider impacts in making this area variously uninhabitable and undesirable.

In such a degraded urban environment, there may be cases in which urgent demolition is unavoidable for reasons of public safety, as has been the main excuse in the neighbourhood. Such cases have become all too common given the long-term neglect of Santarém in general and the Mouraria specifically, and an integrated plan with a strong evidence base and monitoring component should allow managers to identify and plan for the proactive rehabilitation of “at risk” constituents. A responsible administrative body should identify heritage at risk and be responsible for its advocacy through what should be a “social process” of plan making (Healey, 1997).

Recommendations: application of HUL to Santarém

To achieve sustainable development, local governance and planning systems should seek to secure complementarity between the net gains of social, economic, and environmental (and other) indicators within the context of an integrated strategy. A key tenet of this paper is that there is clear support for Historic Centres to reclaim an active, living role in the life of the city, and that such a move would help sustainable development objectives to be met. The value of these areas can be conserved and enhanced in a way that balances heritage conservation with the needs of residents and visitors, and a values-based means of operationalising the HUL approach could provide a resource-efficient yet effective tool for robust municipal spatial planning.

The move to European spatial planning came about through the understanding that the city should be thought of as a living organism in constant evolution, responding to and being shaped by the needs of its resident population (Allmendinger, 2017; Lefebvre, 1974; Massey, 2006), and therefore requires management rather than structured regulation. Similarly, within critical heritage studies (Smith, 2006) the challenge was laid down to democratise heritage discourse, converging on the vital importance of citizen engagement in the historic urban landscape. However, planning in many municipalities in Portugal continues to be something that is done to, rather than with, local people. While there is a limited window for participation in planning policy, the same is not true for planning applications. These are not advertised, nor is there a means for comment. It is not uncommon for neighbours to become aware of development proposals on the day the diggers arrive. This cannot be sustainable, since such an approach disenfranchises communities and undermines the social aspects of sustainable development. As noted, it is communities that bestow value and meaning on places, co-constructing the significance of the HUL. Its management and very survival, then, is dependent on the engagement of people in place.

A series of interviews in place, undertaken by me with a range of participants between June and December 2019, gave me much needed insight into the lived dimension of the neighbourhood, completely missing from the current planning system. For locals, the Mouraria was or still is “one of the more characterful neighbourhoods in the city” but is continuing to suffer from a “complete state of neglect” and degradation. There is an overriding notion that this neighbourhood should undergo material intervention and improvement. Most respondents, given the material state of the buildings, see little aesthetic value left in the neighbourhood at present. However, there is a feeling that all is not lost, that this is not beyond restoration to a more desirable condition, which would be possible given the high level of integrity and perceived authenticity remaining in the material environment. The engagement and participation of local people should be a prerequisite in any intervention, since without this a vital opportunity for increasing knowledge about place is missed.

The contribution of a values-based approach to establishing an evidence-backed strategy is that, through this model, the multiple and intersecting meanings that people attribute to place can be reflected (as far as one model can) in a transparent pathway between problem identification and policy-based solution. But it is worth affirming that the HUL approach is not inherently prescriptive. While attempts have been made to standardise it based on empirical data from Europe and Oceania (Buckley et al., 2015; Colavitti & Usai, 2019; Veldpaus, 2014), such attempts do not reflect the need and ability for the approach to engage critically with the empirical and policy contexts of their places of implementation. The utility of the HUL approach is in its ability to gather and analyse evidence at the interface of several sustainable development indicators, which now includes a keen focus on the conservation (and enhancement) of tangible and intangible cultural heritage (UN General Assembly, 2013). The planning system in Portugal, as in the wider European Union, is the policy vehicle for such an approach to be implemented since it has primary agency in land use decision-making and is bound by sustainable development principles.

Statement of Significance as a snapshot of the HUL

Statement of Significance

The Mouraria de Santarém is an example of a medieval Portuguese “ghetto”. It has retained a morphology reflective of medium to high population density, co-location of workshops/retail and habitation, and visual isolation from the wider city.

Its functional relationship with the Ribeira neighbourhood and its interface with the wider Planalto explain its evolution over time. The presence of mercantile housing is coterminous with the boom in commercial river trade. Changes and alterations can be interpreted within the context of the wider evolution of Santarém.

Substantial damage has been caused both by neglect and by insensitive development over the past 30 years. The result is that the central part of the neighbourhood is a highly compromised historic urban landscape, impacting the integrity of the Mouraria as a whole. This has exacerbated social and economic inequalities in the neighbourhood, while stifling investment.

Damage and erosion of character has resulted from poor management of city centre car parking, lack of coordinated planning for vehicular mobility through the Historic Centre, and by a local over-reliance on the private car, alongside a woeful neglect of much of the built environment.

The approach outlined in this paper presents a process for constructing a new strategy for planning in Santarém focused on the conservation and enhancement of the city’s HUL, and to be put into practice through monitoring those locally relevant values identified above. The Statement of Significance acts as an executive summary of the current state of these values, distilling the core characteristics of the area under study as a quick reference guide. It is a live document, reflecting the evidence base underpinning it, the survey work for which was undertaken in 2019/20. It briefly highlights what is important about the place, why it is important, and how important it is.

The Statement of Significance and the accompanying baseline conditions table (Table 5) based on aggregate negatively weighted results from condition surveys could be useful as material considerations in development management decisions. Since associated value categories are reflections of the local articulation of sustainable development indicators, there should be an expectation that updated planning policy and all permitted development schemes should attend to the conservation or enhancement of each value category in order to enhance the overall significance of the historic urban landscape.

Table 5: Baseline conditions in the Mouraria and each Character Area, 2020

| Classification 2019/20 | |

| Aesthetic | NEUTRAL |

| Amenity & Use | NEGATIVE |

| Social, Community & Cohesion | NEUTRAL |

| Material | POSITIVE |

| Mobility | NEGATIVE |

| Economic & Commercial | NEUTRAL |

| Associative | POSITIVE |

| Environmental & Hydrological | NEUTRAL |

| Scientific & Evidential | POSITIVE |

| Governmental & Political | NEGATIVE |

| OVERALL | NEGATIVE |

Source: own elaboration.

Conclusion

This paper has outlined a practical process for the improvement of urban management through the operationalisation of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach, which has hitherto been more theoretical than practical in content, as a means for achieving sustainable development through the local planning function of Municipal Councils. Such an approach provides clear support in the monitoring and safeguarding of heritage as a resource to be conserved and enhanced. Heritage is a key resource in urban sustainable development, given that heritage and sustainable values are highly compatible, and such considerations are highlighted in successive recent Portuguese legislation relating to planning and conservation.

At the same time, however, the administrative obstacles to really taking these principles forward in effective local planning based in grounded local evidence have often been perceived as too onerous. The HUL approach as built up in this paper through attention to conserving and enhancing value and significance, lowers these barriers and plots a route through them to achieving integrated planning for revitalising communities, building organically on their existing characteristics.

Taking a grounded approach to the HUL in Santarém, local interpretations of the pillars of sustainable development - economic, social, environmental and, indeed, cultural considerations - were transmuted into urban and heritage values. Condition surveys established baseline data for the HUL in perhaps the most marginal neighbourhood in Santarém, the Mouraria, resulting in detailed characterisations of the neighbourhood’s current dynamics. To avoid further decline of the HUL, as an indicator of the overall sustainability of the neighbourhood, these value categories can be usefully deployed to assess all development proposals in the area, ensuring their conservation or enhancement. Likewise, local planning policy can incorporate a values-based approach to urban and heritage management, shifting from a regulatory to a more “spatial” process-led approach which is attentive to indicators such as these and, crucially, with the formalisation of public participatory mechanisms in the system. This is the direction of travel of European, national and regional level planning policy, and so it is at the local level that catch up is needed.

Some of the key outcomes of this work are as follows:

• A values-based approach identifies the significance of a HUL as an important resource in managing sustainable development. This approach can be attentive to local nuances even within a single neighbourhood.

• Municipal planning policy in Santarém is out of date. Not only were key documents produced over a quarter of a century ago, but these are regulatory rather than process- oriented spatial plans. A values-based approach to planning would provide complementarity between social, economic, environmental and cultural processes to support sustainable urban development objectives.

• Tangible and intangible interventions are focused elsewhere in the city in a piecemeal fashion, without consideration as to how the whole city can benefit from an integrated approach. A joined up and citizen-centred approach to the management and monitoring of urban and heritage values are important components of a sustainable approach to urban development, satisfying an important principle of sustainable development.

• Adoption of a Detailed Safeguarding Plan (Plano de Pormenor de Salvaguarda, PPS) for the Historic Centre based on evidence built from a values-based approach would provide transparency, aid consistency in decision-making, and avoid delays and miscommunications due to the need for the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage (Direção Geral do Património Cultural, DGPC) as statutory consultee to be consulted on each planning application in the absence of such a plan.

• For monitoring and facilitation purposes, a specialist team within the Municipal Council should be established within the planning function, to focus on the conservation and enhancement of the HUL as part of a positive strategy for the city’s sustainable renewal.

Despite problems, Santarém’s Historic Centre is viewed with affection, and there remains a remnant and evolving community. People have lived and worked in these neighbourhoods for centuries, and a lot of material reminders of previous epochs remain in situ. Residents still have stories to tell relating to tangible and intangible engagement with the neighbourhood. Much interest remains in exploring the local built environment, appreciating how bits of it seem to be just the same as they have been since time immemorial: the structures, houses and workshops where our ancestors lived, worked and socialised; yet more can be added and overlaid on this canvas. Furthermore, if these neighbourhoods could be rehabilitated and made suitable again for habitation, improving their performance against sustainability objectives, there would be a lesser need for construction of newer housing on greenfield sites.

The case for the physical expansion of development in Santarém is not supported by population growth data. In more general terms, it is recognised that an ever-increasing land take is not sustainable and nor, in an era of environmental crisis and fossil fuel exhaustion, can there be a justifiable case for increasingly dispersed development (Ewing et al., 2011; Artmann et al., 2019). A re-concentration is required, and different models of mobility need to be investigated as a priority. A planning process that could fast track development in its central areas could help exponentially in the integrated sustainable rehabilitation of the city. This can effectively be achieved by adopting a values-based approach to the management and monitoring of development in the city within a targeted strategy. In doing so, a more critical engagement with the historic environment can be managed effectively and balanced with sustainability improvements in the city as a whole.

The approach adopted here can be adapted reasonably effectively for other neighbourhoods in Santarém and, in fact, other cities in Portugal and further afield. Whilst previous studies have sought to establish a transferable template for implementing the HUL approach in different settings, such efforts have tended to have been embedded within the institutionalised instrumental rationality of the northern European administrative structures, and taking for granted a pre-existing fit for purpose management system (Buckley et al., 2015; Colavitti & Usai, 2019; Veldpaus, 2015). The approach taken here involves a more grounded and reflexive approach and, while it inherently involves an intensive empirical element, such work could and should be part of municipal knowledge consolidation processes. In other words, knowledge of a place is a prerequisite to its successful intervention and management, yet local sources of knowledge are often dispersed.

The HUL approach provides an expansive opportunity for identifying and capitalising on this knowledge in a participatory manner, recognising that the safeguarding of the historic environment is not simply a technical task for architects and engineers, but a shared community endeavour. Such a process is necessary for maintaining and enhancing the spirit or sense of place. Finally, far from being an onerous task for a local authority to commit to, implementing the HUL approach through gathering and managing local knowledge can be an opportunity to include a range of local interest groups in day-to-day coordination and management of where they live, building civil society capacity and responsibility in the process. Such an approach can help municipal authorities meet European Spatial Planning aspirations, ensuring that community values are considered just as much as technical values to ensure that historic centres remain vital and appealing places to live and work.