Introduction and research rationale

Food system issues in urban settings are traditionally nearly absent from planning policy, being often regarded as agricultural and rural matters (Pothukuchi & Kaufman, 2000). In the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA), Portugal, this mission has been interpreted heterogeneously by all its constituent actors. Regarding the food system specifically, planning policy worldwide has been slow to face the new demands: greener plans, more efficient local distribution and supply networks, organic production, among others. However, what we can observe in the LMA context is that, while governmental programs are starting to pay attention to such issues, civil initiatives are already very active and therefore demand greater attention.

Recent and substantial research has focused its analysis on the LMA’s food system and planning praxis. The work of Cecília Delgado (2017; 2018), Rosário Oliveira (2014; 2017), Samuel Niza et al. (2016) and Maria João Morgado (2017), in particular, contributed significantly to understanding the specific regional context and its different configurations of urban food consumption, production and supply strategies. Additionally, their works have also provided notable conceptual frameworks that have guided planning policy in recent years.

Oliveira and Morgado noted that, while it was only in 2004 that the first agriculture/food planning strategies were set in place to guide food planning policy change in this metropolitan area, in addition to the generalized master-plans available for these municipalities, in 2017, they concluded: “we can identify in (…) recent years the advent of various initiatives that highlight rising interest and entrepreneurship on behalf of public and private institutions, aiming to increase the dynamics of production, distribution and consumption (…) in the LMA’s region of influence” (Oliveira & Morgado, 2017, p. 23).

With the growing contemporary sustainability concerns, demands to create increasingly local community production and distribution networks of preservative-free organic food production, expose how traditional food supply structures are often insufficient and/or inadequate. New adapted and contextualized planning policies are urgent to address these challenges and the role of these initiatives in contributing to the identification of priority areas for planning policy deserves serious attention.

To dwell into these topics was the departure point for one of the tasks conducted for the WP3 of the SPLACH project, titled “Food security and Sustainability” (Marat-Mendes, Borges, Dias, & Lopes, 2021). The main goal of this task was to study which initiatives are present in LMA and how they are contributing to transforming food system-related dynamics of the region. As part of the task of characterising these initiatives, it was important to understand how food system-related topics are framed in their own agendas, by identifying the conceptual frameworks they mobilize to orient their practice, and comparing these concerns with those shown in previous portraits and scenarios.

To provide a short, five-year timeline to our study, conducted in 2019, we started our diagnosis with data from the 2014 report of the international project ANATOLE - Atlantic Network Abilities for Towns to Organize Local Economy (2014), led by Rosário Oliveira, which brought critical insights into the LMA’s specific urban food system and contributed to drawing a portrait of a post-crisis reality - considered a key steppingstone for planning purposes.

Consequently, the research questions orienting this article are the following: 1) How can the initiatives mentioned by Oliveira and Morgado be characterized?; 2) How is their action changing the scenario identified by ANATOLE questionnaire respondents?; 3) What lessons can we learn from these initiatives and how can they inspire future planning policy?

With the growing contemporary sustainability concerns, demands to create increasingly local community production and distribution networks of preservative-free organic food production expose how traditional food supply structures are often insufficient and/or inadequate. New adapted and contextualized planning policies are urgent to address these challenges; some examples have already been identified and documented, in the LMA region, by the literature with which this article dialogues. These examples, in addition to our analysis of 80 rich and diverse initiatives we mapped, all assemble to make this change even more visible, contributing to a growing international and national body of knowledge (Cabannes & Marocchino, 2018).

Lisbon Metropolitan Area and the ANATOLE report: a brief contextualization

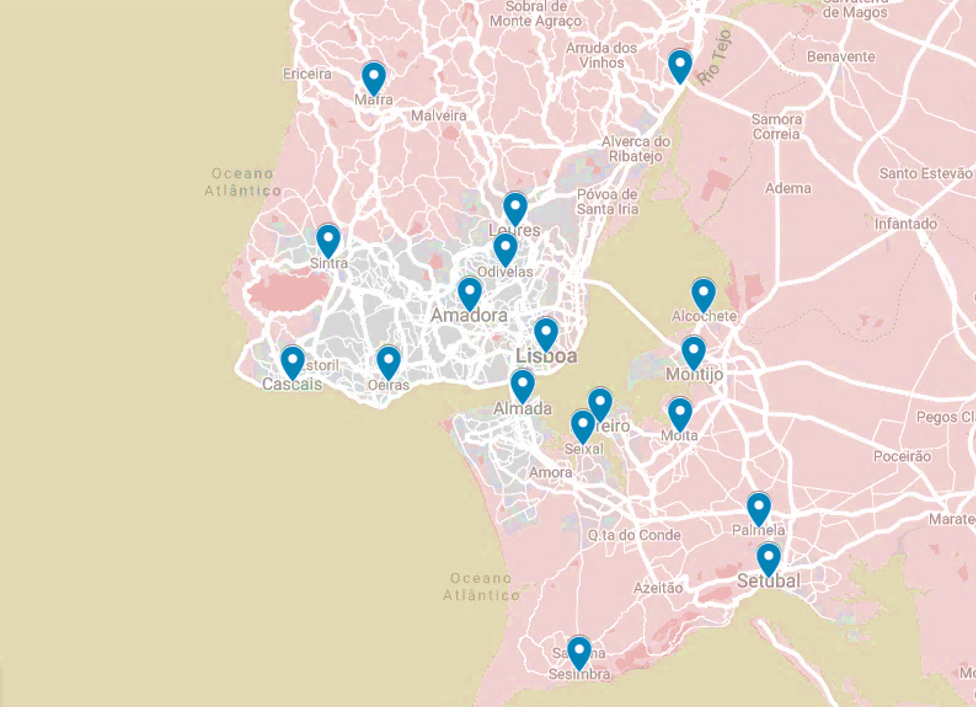

The peninsular LMA territory, separated by the Tagus river, covers a total area of 2.994 km2. As shown below (figure 1), this territory is comprised of 18 administrative bodies, namely the municipalities of Mafra, Sintra, Cascais, Odivelas, Oeiras, Amadora, Lisboa, Loures and Vila Franca de Xira, in the Northern peninsula; and Almada, Sesimbra, Seixal, Barreiro, Moita, Montijo, Alchochete, Setúbal and Palmela in the Southern peninsula.

With a population of 2.854.802 residents , the LMA represents 28% of the 10,047,621 people estimated to live in the entire continental Portuguese territory, making it the most densified area of Portugal. This is critical to understanding the privileged position that this metropolitan area holds in leading national agendas.

In 2019, the SPLACH project consortia aimed to help gather and fill the gaps to provide a comprehensive and coherent body of guidelines to support Portuguese planning practice. Importantly, the ANATOLE report confirmed the lack of articulation between the most relevant planning instruments in the LMA context, including the Planos Directores Municipais (PDMs), the main planning policy instrument at the municipal level, and the food system policy. Likewise, it contributed with a comprehensive, multidisciplinary overview of this region, bringing key insights into its ecological structure, stressing its potential for more long-term, sustainable policies.

The report included results from a questionnaire conducted in 2014 among planning officials working in these 18 municipalities. 62.5% of the respondents appointed the PDM as the most important planning instrument, but also recognized its limitations to orient many issues, including food system policy - about 38% of the respondents said there were no real measures in any instruments (Oliveira, 2014, p. 66).

When inquired regarding food planning policy matters, respondents identified only three types of municipal initiatives related to the food system landscape, namely organic/farmer’s markets (25%), traditional markets and fairs (37.5%) and food basket distribution circuits (25%). Food festivals were also mentioned by 62.5% of respondents as a successful strategy to promote regional specialty products and gastronomic culture (Oliveira, 2014, p. 66). Additionally, 75% of respondents shared they felt focus was often given to “food distribution” and “food production” (62.5%) more often than to other food system stages, such as “processing and manufacturing” or “waste management”. In this questionnaire, respondents recognized that there were not enough strategies to integrate informal initiatives of the civil society with those promoted by municipalities in food planning policies, even though their importance and necessity was recognized (Oliveira, 2014, p. 67). Food security and seasonality, dimensions of economic nature and social and public health concerns were mainly identified with this recognized gap. The planning officials interviewed also stressed the importance of preserving and developing the triad Nature-Environment-Wellbeing (12.5%) when considering integrated, beneficial policies across the three above-mentioned dimensions. The articulation with renewed public transportation and mobility structures was also identified as a main driver of the development of successful food planning policy as well as the ability to coordinate municipal and supra-municipal collaborative strategies (Oliveira, 2014, p. 68).

When identifying the main restraints regarding potential new food planning policies, the lack of scale of food-related initiatives and the resistance to cooperative strategies - leading to municipalities being left to their sole efforts - were appointed as the potentially most difficult ones to overcome by the respondents (Oliveira, 2014, p. 69).

Data and Methodology

The work of WP3 “Food security and Sustainability” of the SPLACH project was conducted under the analytical framework proposed by the “Food for the Cities - City Region Food system” programme, of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Resources Centres on Urban Agriculture and Food Security (RUAF) (Nations, 2021). The FAO/RUAF framework was thus used as the main reference to analyse our mapped initiatives’ discourses. The FAO/RUAF strategic dimensions included: local production, food legislation, food waste, food & health and food security. Two additional lenses were added post-observation by the SPLACH team, namely education & culture and infrastructure. These were included because a great part of the 80 mapped initiatives were found to navigate topics that could not be justly grasped by the FAO/RUAF framework (Pinto, Costa, Marat-Mendes, & Henriques, 2020) (table 1).

Table 1: FAO/RUAF/SPLACH analytical framework

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| FAO/RUAF Local production | May be understood as local production or local distribution. Note that the concept of ‘location’ for FAO/RUAF guidelines is between 30 to 100 km from the city centre. |

| FAO/RUAF Food legislation | Everything in the legislation that mentions something related to food. |

| FAO/RUAF Food waste | Everything that involves food waste and ways to solve this problem. |

| FAO/RUAF Food and health | This guideline mentions specific non-communicable diseases such as diabetes or obesity, but other definitions may be included, such as mental illness or other health problems that: a) green spaces can help to fight disease; or b) may encourage healthy lifestyles. |

| FAO/RUAF Food security | In this guideline we must consider two aspects: a) access to food and b) nutritionally and culturally accepted food. |

| SPLACH Education and culture | Considering efforts of education, training and skill learning that relate to food systems, urban agriculture, healthier lives, among others. |

| SPLACH Infrastructure | Support infrastructure for food production, distribution networks, year-round production, or community learning activities, among others. Material or legal additions brought by each initiative. |

Source: author's synthesis.

In addition to the FAO/RUAF/SPLACH analytical framework, which was critical to situating discourses and thematic concerns, we used two additional systems to characterize the mapped initiatives: one relating to the stage(s) of the food system cycle - production, processing and manufacturing, distribution, consumption and waste management as proposed by Pothukuchi and Kaufman (The Food System, 2000) - table 2, below:

Table 2: Food system stages in detail

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Production | All activities directly implicated in the process of producing food and/or its ingredients (e.g. agriculture) |

| Processing and manufacturing | All activities implicated in the process of cooking, transforming, processing, canning, packaging of food products (e.g. bakery) |

| Distribution | A broad range of activities required to distribute food throughout a specific territory or location (e.g. from local food baskets to industrial transportation from factories to supermarkets) |

| Consumption | Activities and modes of personal food consumption (e.g. vegan, Mediterranean or other diets) and/or patterns of economic consumption (e.g. fresh vs. canned; cheap vs. expensive) |

| Waste management | Activities related to the disposal of waste at the end of the cycle (e.g. composting) |

Source: author's synthesis.

And a second perspective, relating to a typology, previously proposed by Delgado (2017, p. 139) - considering their relevance for European post-crisis contexts- to map urban agriculture initiatives in Lisbon using the following categories: urban allotment gardens, programs and projects, short food chains, urban farms and others, as described in table 3, below.

Table 3: Delgado's typologies in detail

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Urban allotment gardens (UAG) | “Urban food production [that] encompasses agricultural activities with low economic emphasis on material outputs, while using the production of food for achieving other, mostly social, goals” (p. 143). |

| Programs and projects (P&P) | “focus mainly on capacity building, training, and education rather than production. They are promoted by an interesting array of groups of individuals, institutions or public bodies that have started to invest resources into urban agriculture” (p. 143). |

| Short food chains (SFC) | “projects [that] highlight primarily the economic dimension of urban agriculture as they refer to commercial food distribution” (p. 143). |

| Urban farms (UF) | “intentional businesses models taking advantage of proximity to the city, again emphasizing urban agriculture’s economic dimension. The productive farms all work with vulnerable and excluded groups (inmates, disabled people) and (…) they attempt to sell and distribute the products cultivated beyond self-consumption, in order to generate income towards self-sufficiency” (p. 143). In our study, this category was used to describe not only business-oriented initiatives but also those that were experimental in a different food production model or community-led governance strategies |

| Others | This category was only created by Delgado to describe one case that did not fit the former categories and was excluded from our analysis. |

Source: Delgado, 2017.

Our six-month inquiry into this topic allowed us to expand Delgado’s mapping of 29 urban agriculture initiatives to a total of 80 heterogeneous initiatives that are somehow contributing to transforming the LMA’s foodscape. Following a snowball approach (Vinuto, 2014), the main strategy was designed to identify networks created by the initiatives themselves. We started by scanning participatory networks such as Rede Convergir and CIVICS - Impulsa tu ciudad, two open-source databases where citizen-led initiatives can self-locate on a local, national or global scale. Subsequently, social networks like Facebook or YouTube pages were also explored, to identify communication and mission statements produced by the initiatives’ actors themselves. In addition, we searched through the official webpages of the 18 municipalities that constitute the LMA region and mapped initiatives of interest indicated by field specialists.

It should be noted that these 80 initiatives do not represent a comprehensive listing of all the existing initiatives existing in the LMA. Such an ambitious task, if ever accomplished, would rapidly become outdated, as for different reasons some initiatives are temporary, while others have longer lifetime durability (Pereira, et al., 2020). Yet, the experiences selected here offer valuable insights into how seemingly isolated practices are aligned and working towards common goals, showing potential for future collaboration.

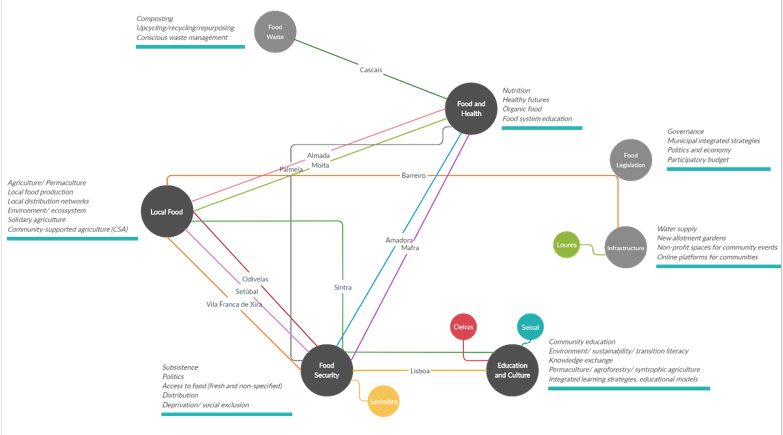

Each of the 80 initiatives mapped in this study was studied and information regarding their practice and discourses was analysed in detail. Subsequently, the SPLACH team collaboratively designed a strategy to let the discourses dictate the topics, concepts and themes stemming from this analysis. This led to the design of a collaborative, multidisciplinary, analytical exercise focused on the content of the actors’ discourses leading these initiatives, included in the texts which were described above. The result was a collection of organic categories or inputs that provided insights into the main conceptual dimensions orienting these initiatives’ actions and an insightful learning map, a revised agenda for future sustainability debates and, consequently, for orienting future, more sustainable, planning policy.

Characterizing emergent LMA initiatives in the food system

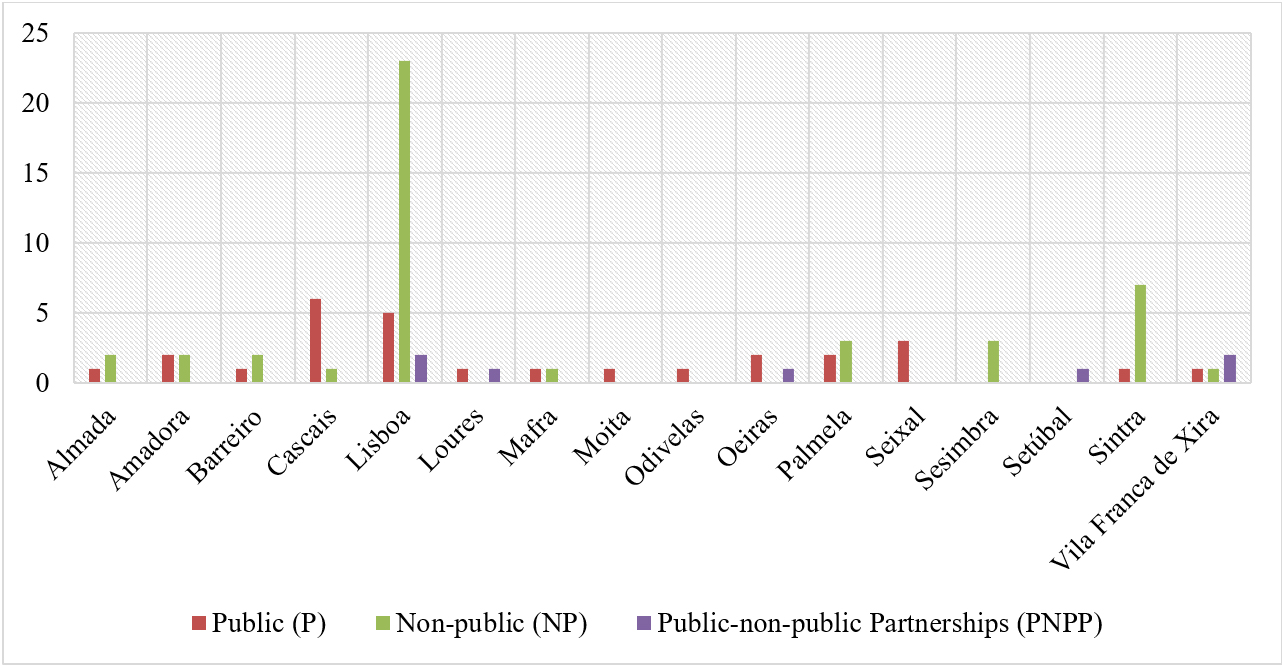

Importantly, only 28 of the 80 initiatives actively interacting with the LMA food system are promoted by public proponents such as municipal or governmental programs. Most commonly, we found these to be the municipalities themselves. How can we characterize these emerging initiatives identified by Oliveira and Morgado in better detail? Figure 2 represents their distribution in the LMA territory.

Cascais, Lisboa and Seixal show the biggest concentration of public initiatives, with 6, 5 and 3 initiatives mapped, respectively. Amadora, Oeiras and Palmela follow, but only with two municipal initiatives mapped, each. A total of 45 of our mapped experiences fall into the “non-public” category, which we used to describe all initiatives promoted by entities other than public, or municipal, actors. These ranged from private entities to cooperatives, to citizen groups, local development associations and non-profit organizations, to name a few. Lisboa, Sintra, Palmela, Sesimbra, with 23, 7, 3 and 3, respectively, is where most of these initiatives were located. We found only 7 to be promoted by partnerships between public entities and others and they were only found in the municipalities of Lisboa, Loures, Oeiras, Setúbal and Vila Franca de Xira, with Lisboa and Vila Franca de Xira leading with 2, each.

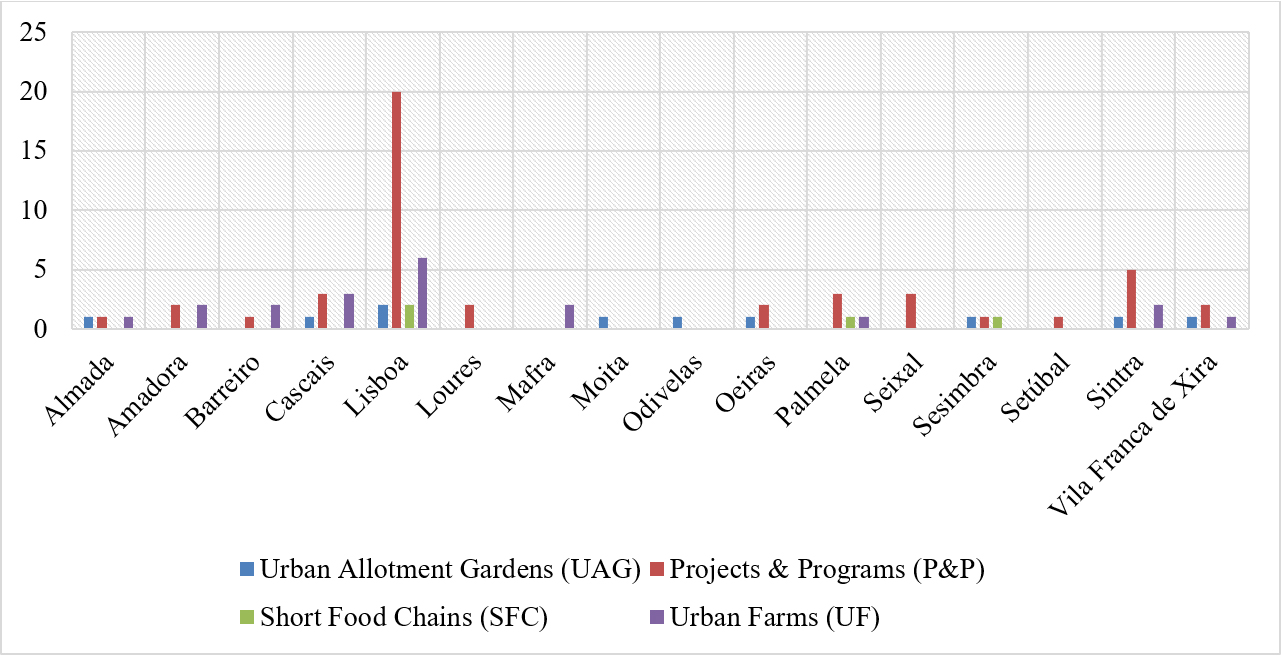

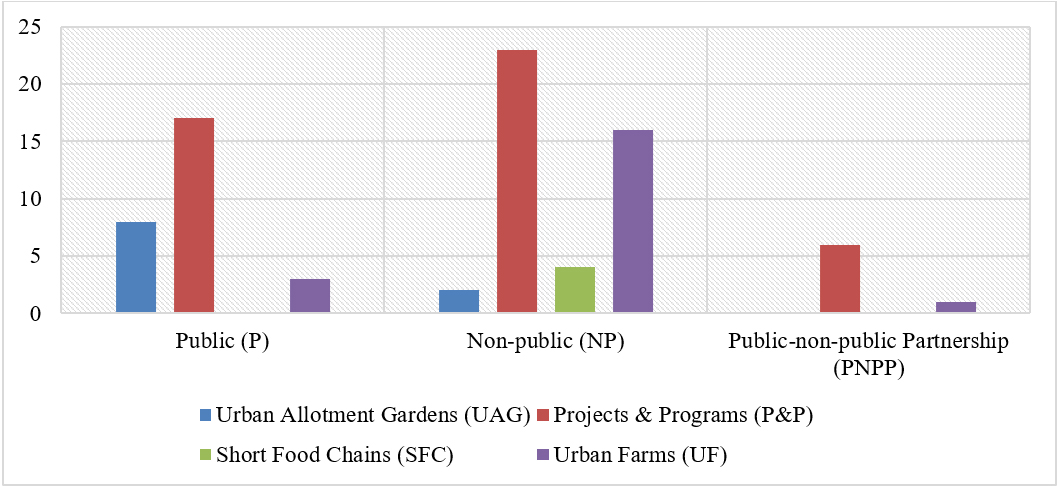

In figure 3 we illustrate how most initiatives we found fell largely (a total of 46) into the category “Projects and Programs” (P&P) and were mostly found in Lisboa, Palmela, Seixal and Sintra. Additionally, 30 initiatives were categorized as “Urban Allotment Gardens” (UAG) or “Urban Farms” (UF) and only four (4) were pinned as “Short Food Chains” (SFC). Lisboa was the only municipality where all types were found to coexist.

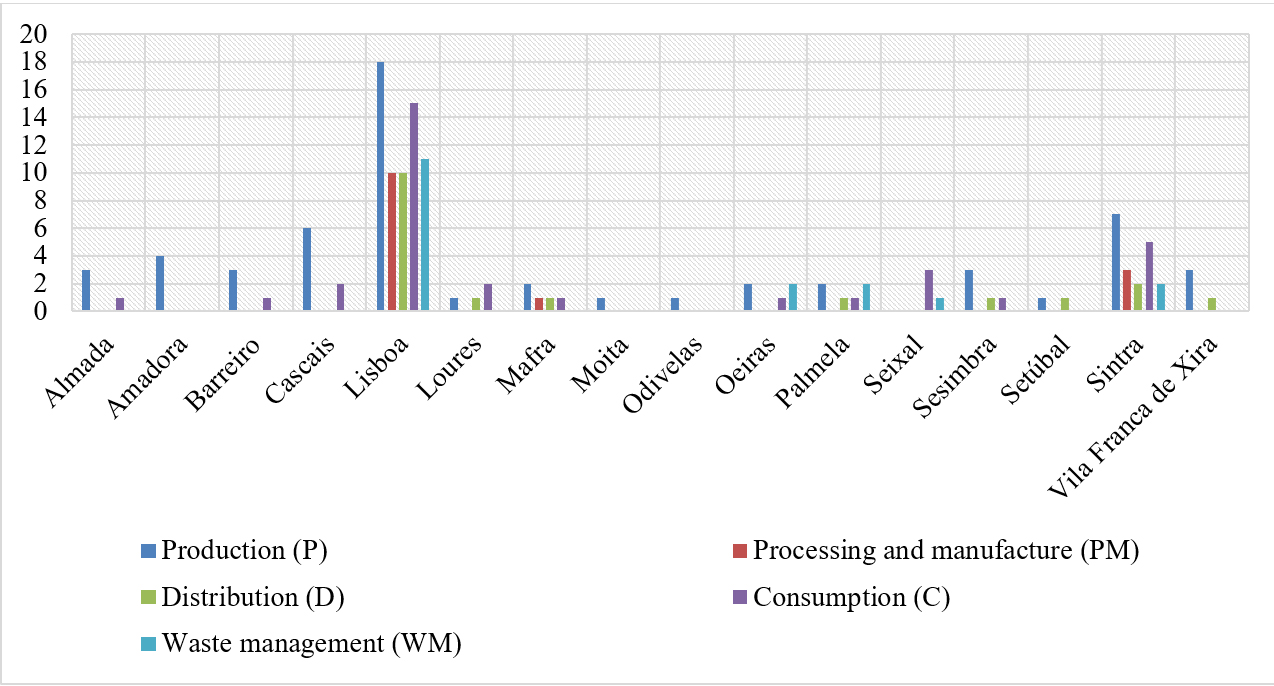

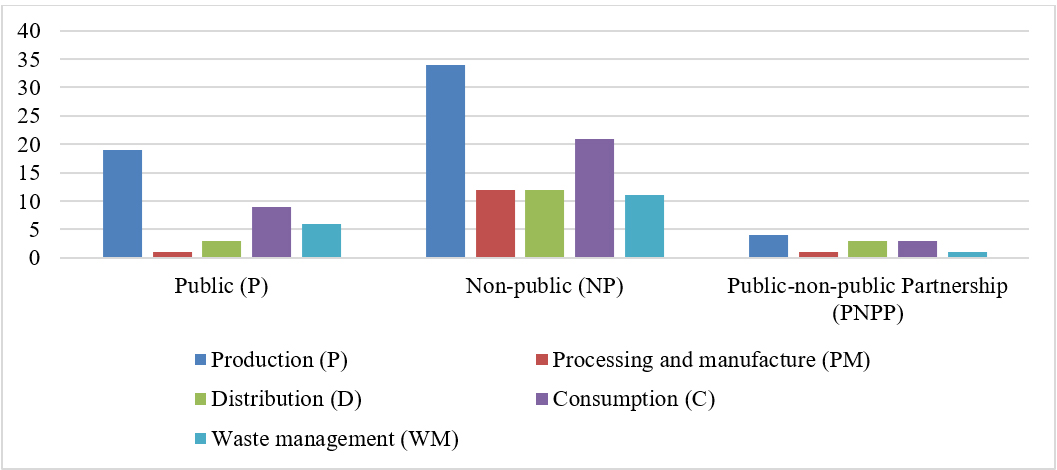

In figure 4, the relation between the territorial distribution of the mapped initiatives and the food system is shown. Lisboa and Sintra were found to have the most homogeneous distribution, paying similar attention to most food system stages, excluding production (P). In fact, a focus on production (P) stage is prevalent among 57 of the mapped initiatives. The next prevailing focus was found to be consumption (C), with 33 initiatives; then, distribution (D) and waste management (WM) with 18 each, and only then do we find 14 initiatives with a focus on processing and manufacturing (PM).

Tracing food system discourses: how LMA initiatives frame their own action

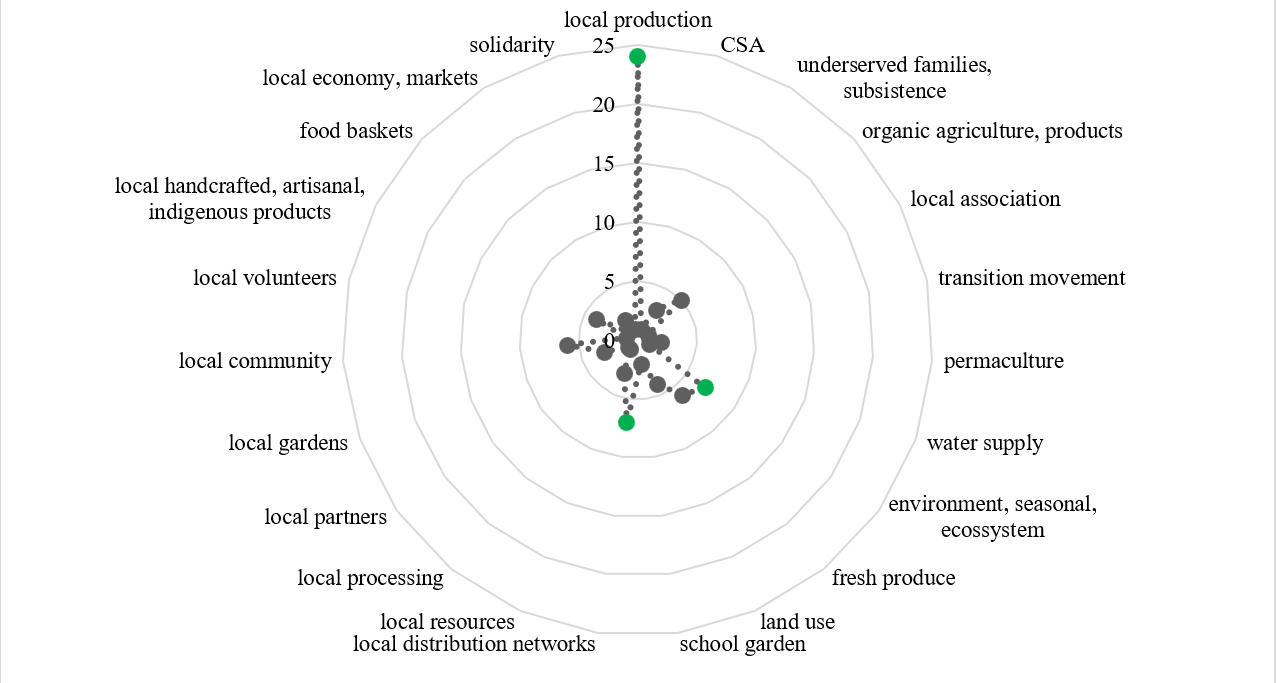

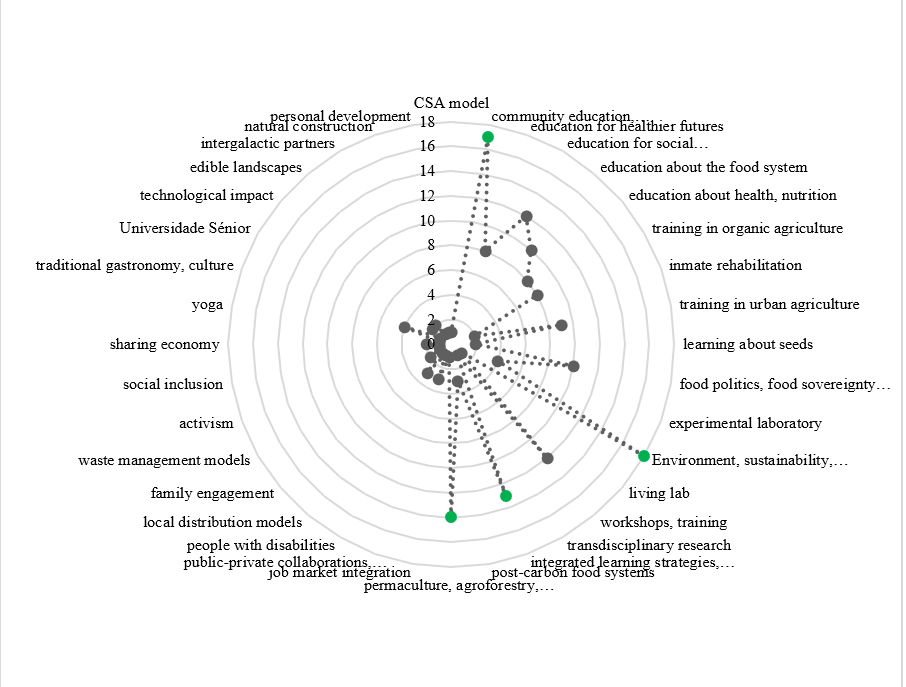

To characterize the mapped initiatives we relied on their own published mission statements and outreach communication efforts. We sought to interpret “what they do” and “who they are” from their own discourses while simultaneously attempting to grasp how they are mobilizing certain conceptual universes to set their food system agenda. The results are presented below in a series of spider graphs representing these conceptual clouds, systematized according to the FAO/RUAF/SPLACH framework.

The first of this series is the summary of trends in topics of interest demonstrated by all 80 initiatives mapped in the LMA, illustrated in figure 5, below.

Highlighted in green we can identify the three most frequently refereed topics of interest for the entire LMA region, namely, fresh produce, local community and education, food literacy. These topics are consistent with our previous findings, especially since the most prevalent stage of LMA’s food system is production (hence, the increase in availability of fresh produce) and a lot of initiatives mention education and training objectives. Next, we explored how these initiatives are positioning their action within food system debates by fleshing out these discourses according to the FAO/RUAF/SPLACH framework.

Observing how these initiatives address the “local” dimension (as previously noted to be significant when addressing “community”) leads to identifying topics of local production, environment, seasonal, ecosystem and local distribution networks as the most predominant.

In relation to the circumstances in which these initiatives address issues pertaining to legislation, or regulatory matters, we found that municipal regulatory frameworks, and participatory budget were the most frequently mentioned topics. This category was created to include all cases in which specific municipal regulatory frameworks were produced or changed for the creation or development of the mapped initiatives. The participatory budget was found to be one regulatory framework through which food planning policies could explore hidden potentials, as it is an active resource with significant public investment that seems to receive citizen attention.

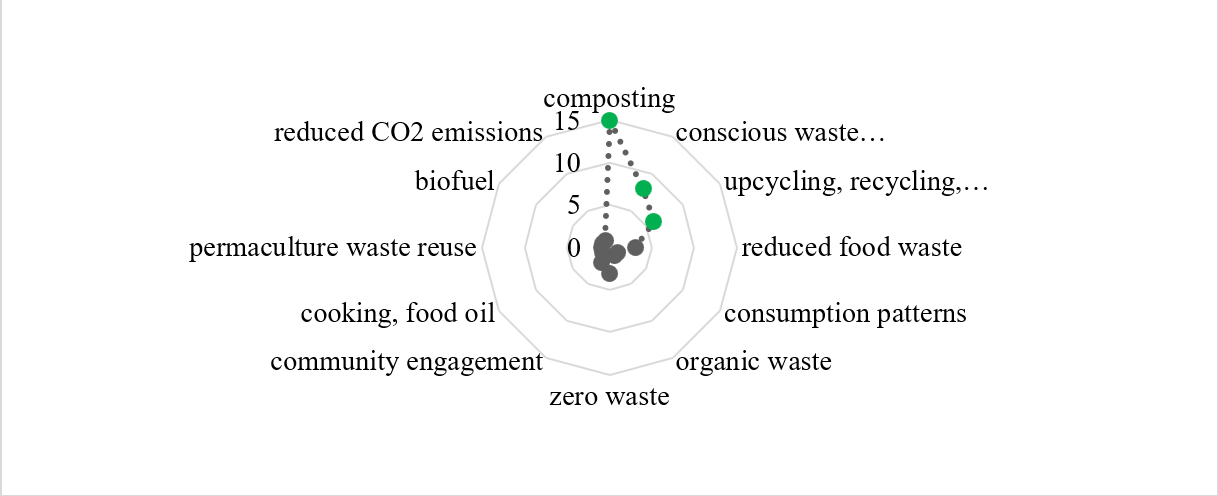

An analysis of how these initiatives address matters of food waste and waste management concerns points to composting, conscious waste management and upcycling, recycling or repurpose as the most predominant topics (figure 7). These trends seem to illustrate an increased attention to composting solutions in addition to the already-known recycling strategies. Consequently, an increasing number of municipal programmes providing domestic and community composters to communities could be a sign that a shift in attitude is starting to be noticeable in this domain.

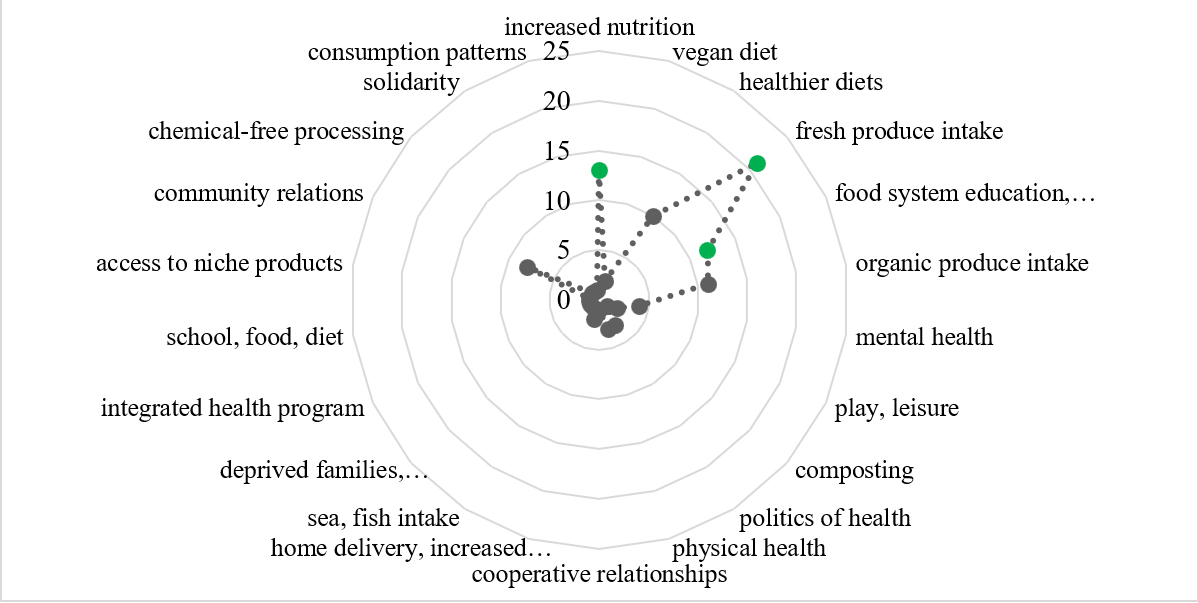

Moreover, these initiatives showed interesting relations with the ideas of health, with references to fresh produce intake and increased nutrition being predominant in these discourses (figure 8). Accordingly, concerns regarding food system education and literacy were also found to accompany most of these ideas. However, interesting exceptions were also found, as more than one project showed concerns regarding the connection of diets and mental health, others mentioned the idea of healthy community and/or social relations and, in a few other cases, health was also found to be discussed as a politically determined condition.

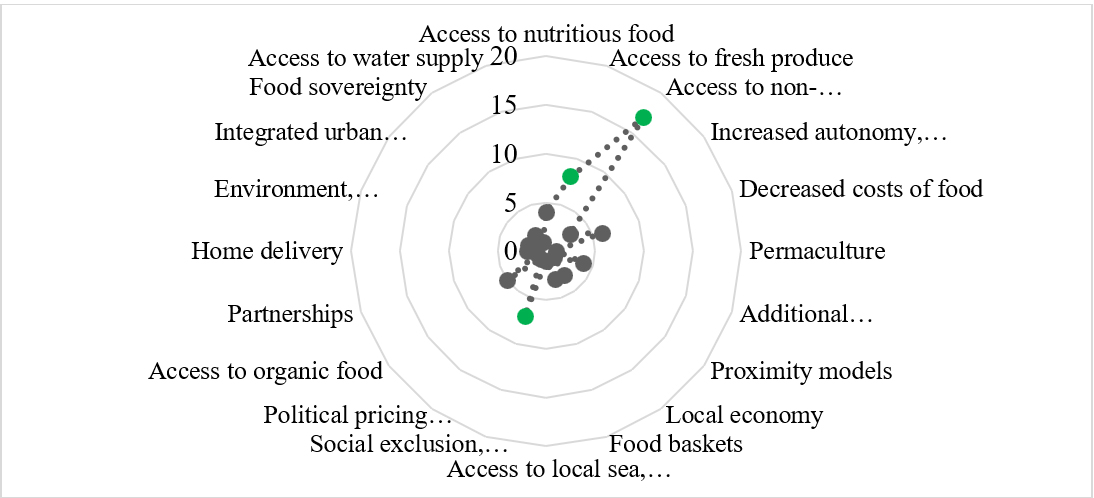

One important discovery was that the discourses associated with food security were often found to address access to non-specified food, access to fresh produce and matters of social exclusion, deprivation, poverty (figure 9).

Additionally, it proved fruitful to add the SPLACH category Education and Culture, as we found important references to environment, sustainability, transition literacy, community education, knowledge exchange, permaculture, agroforestry, syntrophic agriculture and integrated learning strategies, educational models (figure 10).

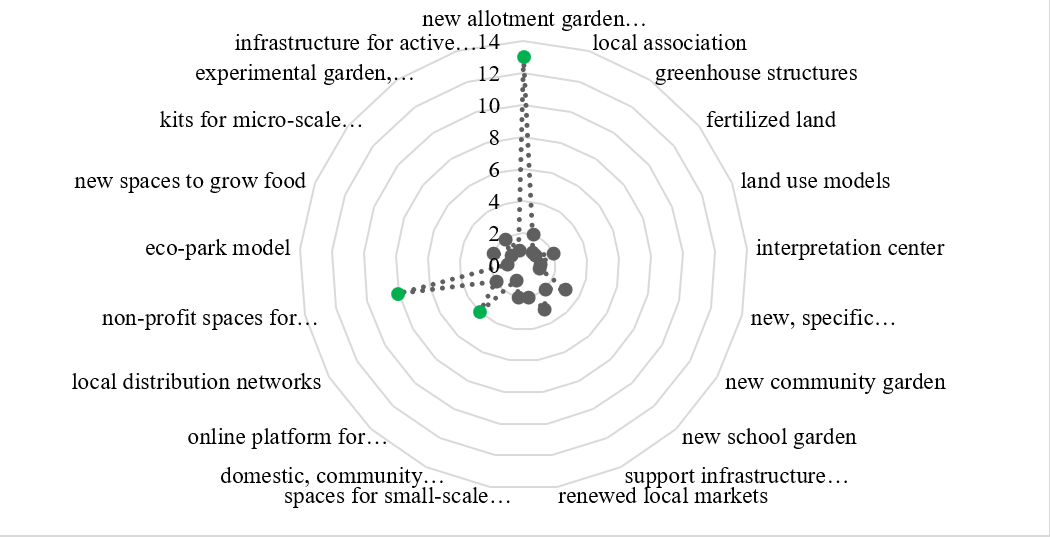

Lastly, when observing how these initiatives relate to the Infrastructure analytical dimension, we find that new allotment garden spaces, non-profit spaces for community events and online platform for communities are the most frequently mentioned topics (figure 11).

Comparing the ANATOLE questionnaire scenario with the LMA foodscape today

The scenario outlined by the 2014 ANATOLE questionnaire described a somewhat unplanned relation between the municipalities and food policies. To analyse the changes occurred in this five-year period between 2014 and 2019, we looked at some of the main points identified by the ANATOLE questionnaire respondents, in the present time.

The first concern was the identification of types of detected municipal initiatives. In this questionnaire, respondents claimed most attention was given to three types of municipal initiatives related to the food system landscape, namely organic/farmer’s markets (25%), traditional markets and fairs (37.5%) and food basket distribution circuits (25%).

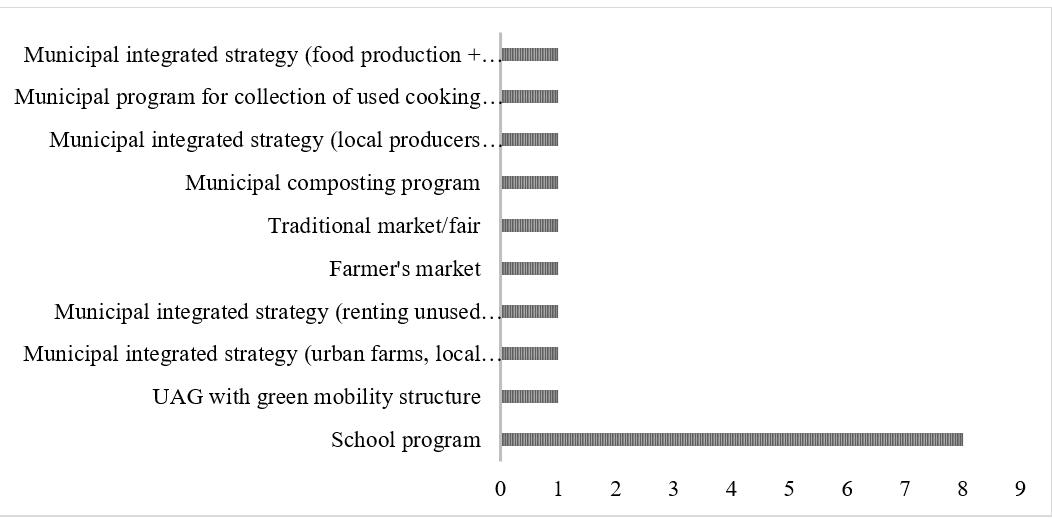

Figure 12 shows a simplified typology of the types of initiatives we mapped as being fostered by public entities. Below, figure 12 shows that most municipal initiatives (17/28) fall under the category of “Programs & Projects” (P&P).

These 17 municipal P&P initiatives, however, do include in 2019 a diverse range of objectives. As figure 13 shows eight (8) of these P&P are in fact school programs. Organic/farmer’s markets, traditional markets, and fairs, as well as food basket distribution circuits still exist but we found they were now being promoted in partnerships composed of public (municipal) and non-public entities. Looking at figure 13 we can also see that we found no public municipal initiatives promoting short food chains (SFC) but we did find four non-public initiatives promoting this type of practice. Public entities now seem to focus increasingly on providing new urban allotment gardens (UAG) and school programs promoting urban agriculture knowledge and literacy.

Next, we looked at where municipalities were focusing their efforts on. In the ANATOLE questionnaire, 75% of respondents shared they felt focus was often given to “food distribution” and “food production” (62.5%) more often than to other food system stages, such as “processing and manufacturing” or “waste management”.

Figure 14, below, demonstrates that this point seems to remain unchallenged. Food production is indeed where most efforts seem to go when promoting initiatives both among public (19) and non-public (34) proponents. However, distribution is no longer the food stage under greater attention by either proponent; consumption is now the focus of public and non-public (21) initiatives, following production. We also found, in 2019, more non-public entities promoting distribution initiatives (12 vs. 3).

Another point identified by the ANATOLE report was that there were not enough strategies to integrate informal initiatives of the civil society with those promoted by municipalities regarding food planning policies, even though their importance and necessity was recognized. Food security and seasonality, dimensions of economic nature and social and public health concerns were mainly identified with this recognized gap.

If we look at figure 6, presented earlier in this article, regarding topics concerning “legislation”, we can see that this concern is pivotal for many initiatives, with discourses relating to municipal regulatory frameworks, and participatory budget scoring the highest numbers of mentions. The insight we gain from this data is that not only might we be witnessing a greater importance of providing regulatory frameworks to involve informal initiatives of the civil society in municipal strategies, but also that the specific program “Orçamento Participativo” (participatory budget) is becoming an effective tool to achieve this goal.

However, in figure 9, concerning “food security”, municipal policies of this nature were not registered in the initiatives’ discourses, pointing towards a) another understanding of what “food security” means for these actors; or to the fact that b) the civil society and municipal initiatives we mapped do not frame their concerns in the same way as the ANATOLE respondents did, in 2014. Despite the discourses relating to “food security” prevalence on topics relating to access to fresh produce or non-specified food, or topics of social exclusion, poverty and deprivation, these initiatives seem to be framing the issues independently of municipal intervention. We believe this to be a significant finding to reflect in the development of future food planning policy.

The following topic of discussion was the ANATOLE questionnaire identification of the importance of preserving and developing the triad Nature-Environment-Wellbeing (12.5%) when considering integrated, beneficial policies across the three above-mentioned dimensions.

When considering figure 4, summarizing the trends in topics of interest for LMA across all analytical dimensions, we find that this triad is actually present in the most commonly found topics, namely fresh produce, local community and education, food literacy, closely followed by concerns with education and training. We do find that concerns around the environment and sustainability also often occur, as well as concerns with the “local” dimension, represented by topics such as local community or local distribution, orienting the discussion towards wellbeing. Indeed, figure 10, illustrating how these initiatives consider matters relating to education and culture, topics such as environment, sustainability, transition literacy, community education, knowledge exchange, permaculture, agroforestry, syntrophic agriculture and integrated learning strategies, educational models all score an elevated number of mentions, reinforcing the idea that efforts are being made with the triad Nature-Environment-Wellbeing considered in an integrated manner.

The articulation with renewed public transportation and mobility structures was also identified as a main driver of the development of successful food planning policy as well as the ability to coordinate municipal and supra-municipal collaborative strategies. Hence, the discourses categorised as pertaining to topics of “infrastructure” do show some concern and efforts regarding mobility structures, particularly green mobility, and micro-scale mobility connections. Some new bike lanes were integrated in new eco-parks recently constructed in the LMA region, as well as more pedestrian routes; however, public transportation solutions did not come up in these discourses. The only municipal strategy we found to be comprehensive and including mobility solutions, along with urban allotment gardens and health concerns, with jogging routes included, was the project “aHorta - Hortas no coração da cidade” approved in 2015 in the municipality of Barreiro (Barreiro, 2021, p. 26).

Finally, the ANATOLE respondents identified the lack of scale of food-related initiatives and the resistance to cooperative strategies - leading to municipalities being left to their sole efforts - as the main restraints (and potentially most difficult to overcome) regarding potential new food planning policies.

As previously discussed, and best illustrated in figure 5, the “local” dimension is central to the initiatives’ discourses and practices. With concerns regarding “local food production” (pointing towards food production) and “local distribution networks” (food distribution), among “local community” (local consumption), “local economy” (local processing and manufacturing, consumption) and “permaculture” (including reuse of “food waste” in its premise), we seem to find all food system stages represented in this analytical dimension. In fact, it is unclear why the planning officials identified “lack of scale” as a restraint regarding potential food planning policy as it is consistently not perceived as a restraint in these actors’ discourses in 2019. The second identified restraint, “resistance to cooperative strategies”, is also unclear. Where is the resistance coming from? Despite having only identified seven (7) active public and non-public partnerships during the six months this research took place, they were proposed by the public authorities, meaning there is at least some cooperative attitude in these cases. If resistance is coming from non-public entities, that would still be difficult to grasp as most initiatives describe their own mission as filling a gap in services for the “public good”.

Yet, those who do not frame their practice in municipal participatory budgets, for instance, might still express their wish for an increased involvement with local authorities and lament the post-2008 crisis economic ripple effects that depleted public funding available to support local experiences. Nevertheless, another cooperative resistance might be at play, which would be the inter-municipal cooperation resistance. This type of cooperation is well documented in literature and in policy frameworks; however, since food planning policies are insufficient, we could understand why respondents would claim there is a certain resistance to cooperative strategies. To help identify possible focus points of cooperation and mutual learning, we prepared a final chart, represented below, on figure 15, to display the territorial distribution of most frequently mentioned topics of interest, per municipality .

Lessons for future planning policy

Throughout this article, we sought to respond to the first two research-orienting questions, namely, (1) how we characterized the mapped initiatives and (2) how their action was changing the scenario identified by ANATOLE respondents. In this final section, we summarize the analytical aspects of these answers and attempt to answer our third question and (3) flesh out lessons to be learned from these initiatives and how they can inspire future planning policy.

The content analyses we cross-referenced with FAO/RUAF/SPLACH analytical dimensions provided fruitful information about the main topics and areas of influence of these initiatives and also helped to identify possible less developed arenas, which are potentially significant for food planning policy research. We organized this concluding section under three subsections, as follows: i) a summary of our main findings; ii) following contributions to a research agenda; and iii) preliminary contributions to a planning policy agenda.

Summary of main findings:

Our findings were shown to be consistent with previous literature, particularly with Delgado’s claim that additional political debates are necessary to re-frame understandings of urban agriculture (and we add about the food system as well) (2017, p. 150). In Lisbon, we found 17 mentions relating food and health politics, which is illustrative of how some initiatives could be adopting a critical framework to guide their practice. When comparing our findings to those of the 2014 ANATOLE questionnaire, the experiences studied suggest the possibility of ongoing transformations.

1. From a scenario of municipal programs focusing mostly on organic/farmer’s markets, traditional markets/fairs and food basket distribution, figure 13 demonstrates that in the mapped public programs and projects (P&P), where these fairs and markets were also found, we now perceive eight initiatives which are in fact school programs. Overall, municipal policies seem to be shifting from a consumer-oriented strategy to an education-oriented one, through the increasing provision of new urban allotment gardens (UAG) and school programs promoting urban agriculture knowledge and literacy.

2. However, we still found that the focus on food system stages is shifting more slowly. From a focus on “food distribution” and “food production” we now see a focus on “food production” and “food consumption”.

3. We also noticed that there seems to be an increasing number of strategies to integrate informal initiatives of the civil society in programs promoted by municipalities through the increasingly popular tool of “participatory budgets”. However, this shift is not increasing focus on problems of “food security”, a gap identified by the ANATOLE questionnaire respondents. It is imperative to understand if there are different perceptions of what “food security” means for public programs and initiatives of the civil society, as our findings seem to indicate a potential critical gap.

4. The triad Nature-Environment-Wellbeing was deemed pivotal, in the 2014 questionnaire, when considering integrated, beneficial policies. We found that concerns around these topics are central to the mapped initiatives, both those promoted by public and non-public proponents, and conceptualized in an integrated manner. In addition, the “local” aspect of the food system was often dominant, reminding us of the fourth dimension, space, whose consideration is determinant for any food planning policies to succeed.

5. Despite being identified as a main driver of the development of successful food planning policy, the articulation between public transportation and mobility structures with the food system proved to be virtually absent from initiatives in the LMA. Although discourses identify the importance of this articulation, only one municipal program in Barreiro (“aHorta - Hortas no coração da cidade”) presented a comprehensive proposal regarding this topic. This could be primarily attributed to public transportation and mobility structures being one dimension that is heavily dependent on public infrastructure and resources, which means initiatives of the civil society would have less room for transformation.

6. Finally, two main restraints regarding potential food planning policies identified by the ANATOLE questionnaire respondents, namely the lack of scale of food-related initiatives and resistance to cooperative strategies, were subjected to analysis. We found that due to the weight of the “local” dimension in these experiences’ discourses scalability seems to be out of the scope of this informal 2019 agenda. We also found no evidence in literature of scalability being critical to the success of food planning policies; on the contrary, most studies point to the importance of locality and small-scale interventions as best suited for this type of policy. Lastly, findings regarding the identified resistance to cooperative strategies are unclear. While we only found seven active public and non-public partnerships in all the 18 municipalities, they were first promoted by public authorities. We hypothesized that the resistance that respondents identified could be associated with inter-municipal cooperation, in which case we prepared a cluster analysis (figure 16) showing points of possible inter-municipal cooperation centred around topics of interest for food planning policies and agendas.

A few notes on the LMA food system, as posited by the 80 initiatives studied:

1. The “food waste” dimension is now mostly represented by discourses around “composting”, indicating that the recycling narrative is no longer the only way to think about sustainable waste management. We encountered an increasing number of municipal strategies providing community and domestic composting tools and education programs:

2. The analysis of food and health was perhaps the most insightful, in the sense that health is a complex topic. Our content analysis showed that most mentions relate to fresh produce intake and nutrition as well as education and literacy efforts. Several studied experiences were observed to address more holistic interpretations of the relationship between food and health. These ranged from conciliating physical health with mental health, community conviviality with mental health and social inclusion and even political debates about the medical establishment and how food intake is taking a toll on health at a societal level. Digging deeper into how health is being conceptualized by these actors and what they identify as challenges they wish to address through their practice would certainly enlighten research focused in this dimension and how planning policy could take this relation into account.

3. The food security analysis did show cause for concern and recommendations for future research. There are mentions to contributing to fight poverty and social exclusion in discourses; however, we could not find any consistent or integrated materialization in public or non-public initiatives. We did notice, nonetheless, interesting experiences associated with proximity models or political pricing of organic produce. These findings could be particularly interesting to research projects in light of the second objective of the 21st century Sustainable Development Goals, Zero Hunger.

4. Additionally, education-associated activities proved to be increasing and the education and culture analysis was particularly insightful. We found mentions to transition literacy, knowledge exchange or integrated learning strategies in most of the mapped initiatives and this was certainly one of the dimensions where we observed the biggest variety of topics. From living labs to community education passing through transdisciplinary research and intergalactic partners, the conceptual world of education and culture is one of the richest, most diverse and one of the most prolific areas for further research.

5. Lastly, the infrastructure-related content analysis showed that the creation of new garden spaces is the most common reference, followed by non-profit spaces and online platforms. These findings might reflect our post-2008 crisis context (Delgado, 2017, p. 140) as well as our current crisis context related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ii) Contributions to a research agenda:

1. With a significant distance, the category Programs and Projects (P&P) aggregates the highest number of mapped initiatives (47 out of 80). This category gathers both municipal programs and independent projects and a thorough investigation could help gain additional insight - are we really living in the Age of Projects (Novak, 2008) or do we need to reconfigure our conceptual apparatus?

2. We could not identify any actors in the food system arena in Alcochete nor in Montijo. Are these municipalities not investing in this topic at all or are these territories’ experiences not attaining enough outreach media efforts? Could their specific context also call for some reflection on the inexistent need to develop autonomous initiatives acting alongside the public system?

3. Excluding the category programs and projects (P&P), which scores highest among both groups, public proponents seemed to focus more on urban allotment garden (UAG) spaces while non-public proponents scored higher on urban farms (UF). When looking at the food system stages, public proponents focused more on “production” and “consumption” while non-public proponents seemed to distribute more evenly across all food stages, even though “production” was also the focus. Is food production the go-to escape route when the intent to transform the food system landscape is present (Brinkley, 2013)?

4. Interestingly, however, “processing and manufacturing” is the food system stage with least attention from both types of proponents - and initiatives impacting this stage are only registered in Lisboa, Mafra and Sintra. According to Maria João Estorninho, (2017) this phenomenon might be indicative of a structural challenge when considering LMA’s food system - while the provision of food seems to be a constitutional duty of the Portuguese public authorities, the food processing and manufacturing industry is dominated by private actors. Further interdisciplinary research could be necessary to assess this phenomenon further.

5. This work could contribute to inform case studies selection for future research. Despite planning practices often underestimating, at least during a certain time, more organic actions of local communities, embedded in civil society and spontaneously growing in territories (as will be the case of many of those observed in this study), the fact is also that policy-makers and public practitioners often end up adopting (or promoting) most of these practices. The evolution of the regulation mechanisms and governance forms, which are inherent to the cases we studied, is naturally an ongoing process. The development of adaptation dynamics of many of these governance mechanisms (including the absorption by the public or private sector) are probable. Naturally, the risks of instrumentalization (by political objectives, by markets, by specific group interests) are always part of this equation and should be considered. By the same token, also frequently there is misunderstanding by the regulators of the importance of flexibility, informality and other specific attributes that can be at the centre of the governance mechanisms which enable the success of these actions and experiences. The potential and unpredictable consequences of this institutionalization often end up challenging their sustainability and may be even affecting the resilience of those projects. Nevertheless, the absorption by planning and public policies of the generality of the know-how developed by these initiatives and collectively accumulated in those communities will naturally be important for their development and mostly for their spreading within these municipalities, and in all LMA, as well as for the mainstreaming of these best practices in terms of policy action and planning practices.

6. We need to acknowledge that the context we are discussing is complex and a descriptive exercise as such could not account for its richness and plurality. From initiatives fighting for fairer consumption and distribution models (such as the community-supported agriculture (CSA) model, featuring mostly in Almada), to actors fighting for chemical-free and nutrient-rich food products, to political pricing strategies, we could find important lessons to take from each of these 80 rich experiences and thus recommend future research building on the data collected.

7. The relationship between “food security” and “poverty” should be further studied, particularly, in terms of how it is perceived by the actors promoting action in this scope. This is a critical issue if food planning policies are to help address “food poverty” and improve health indicators in the LMA territory. From the consonance or dissonance in this understanding could lie the difference between successful strategies or wasted opportunities for meaningful food security planning policies.

8. Are we living in an era where educational goals must exist by default or are these initiatives really moving towards a culture of shared knowledge and peer learning? Additional research is needed if planning policies are to foster social emancipation, increased literacy and autonomy in their communities. We hope the scheme developed by our study and presented in figure 15 is used and appropriated by studies aiming to orient thematic proximity in future food planning policy.

9. Is funding only available for the creation of new production spaces - meaning all other outputs must be online or non-profit? Additional interdisciplinary research could contribute to understanding this phenomenon by following the spending of public and private funding efforts in the food system landscape. This point is particularly relevant in what could be anticipated as a post-COVID-19 crisis, which affected all relationships and spaces without a digital equivalent.

iii) Contributions to a planning policy agenda:

1.The first contribution to a food planning policy agenda in the LMA is the recommendation that interested planning officials use the cluster analysis illustrated in figure 16 to identify starting points to foment inter-municipal cooperation and critical thematic focal policy design. We are confident that our comprehensive identification of topics harvested from actors’ discourses could offer key insights to understand the overall food system transformation but also to potentially select cooperation networks that could offer good conditions for experimental programs, increased and shared knowledge exchange and mutual learning practices and groups.

2. Our following contributions mostly derive from the gaps identified in the ANATOLE questionnaire, illustrative of the perceptions of planning officials, and our analysis of the 80 initiatives’ discourses, illustrative of their perceptions about the food system in the territory. Consequently, we recommend that the Plano Director Municipal (PDM) assumes a more centralized role in orienting food planning policy. This recommendation is grounded on our understanding that PDMs must include an effective strategic planning orienting logic that involves different stakeholders in the field, including those pertaining to the civil society. This strategic planning orientation should start at a diagnosis stage and continue towards the definition of concrete projects or programs, accepted by all committed stakeholders. This orientation should dialogue with national and international documented policy and practice recommendations and should go beyond generalized trends, electoral cycles or other power relations.

3. Additionally, our findings point towards the fruitful continuation of programs such as participatory budgets, with a recommendation to mind the “institutionalization” of informal, micro-scale experiences that emerge spontaneously in particular contexts due to historical, social or economic settings. We do not know if scalability or replicability is an asset in such cases and this attempt could lead to unforeseeable effects.

4. Finally, we would recommend an increased presence of planning officials “in the field” to foster a culture of daily and permanent dialogue and communication. The promotion of flagship projects or good practices might be seductive to elected representatives aiming for short-term popularity; however, the continued planning officials’ engagement with neighbour municipalities, informal, community, cooperative, associative or citizen-led initiatives might be critical for a deep-rooted success of future food planning policies striving for grounded, context-dependent Sustainability.

As a final remark, we hope our contribution has achieved its goals of characterizing the initiatives found to be transforming the LMA food system and how this transformation is framed and oriented; we similarly hope to have contributed to understanding in what ways the LMA food system scenario is changing through their action; and, finally, we hope to have been able to identify relevant lessons to be considered by future planning policy aiming for long-term sustainability grounded on inter-municipal cooperation and mutual, continuous learning.