Introduction

“Today, there is no doubt for anyone that rock music dominates all other cultural phenomena worldwide” (Paraire, 1992, p. 9). In other words, this music genre is deeply rooted in the everyday life of individuals, particularly young people. Based on this centrality of rock in life, Paula Guerra (2015) considers it an absolute beginner, in the sense that the emergence of this musical genre entailed a rupture with the standards that were socially established, namely through the dissemination of the legendary epitome ‘sex, drugs and rock'n'roll’1.

In this article, we intend to problematize and deconstruct this epitome that marked and still marks rock'n'roll since its emergence in the Anglo-American context, today globally transposed, constructed, and reconstructed. Therefore we consider the social representations/reconstructions conveyed by actors of the national rock scene, concerning consumption, sexuality, and lifestyle. In other words, by analysing consumption, we sought to understand the habits and routines of licit and illicit substance use, as well as its association with the rock music context. By exploring sexuality, the aim was to understand their experiences and affective practices, as participants in the rock scene. Finally, by reflecting on lifestyles, we tried to study their daily individual and collective practices, within their respective frameworks of social interaction, from the perspective of actors in the Portuguese rock scene.

Dangerous links between youth, rock music and drugs

Over the decades, there has been a tendency for youth subcultures to be associated with deviant behaviours, namely related to the excessive consumption of alcohol, tobacco and illicit substances2, as a referential practice of the different subcultural groups linked to rock music (Brake, 1985; Savage, 2002). In fact, “since its beginnings, rock culture has been associated with excesses (celebrated by the aphorism, sex, drugs and rock ́n ́roll)” (Guerra, 2010, p. 115). Therefore, understanding the relationship between rock music, psychedelia and sexuality is not just an academic exercise. It is also a necessary part of understanding how psychotropic consumption practices and sexual attitudes are apprehended and represented by young people (Frith & McRobbie, 1978). This premise has been and continues to be the subject of study of different researchers, notably by Hebdige (2004), who argued that

“(…) rock performances have come to be associated, within the popular imagination, with a whole series of disturbances and disorders, from cinema seats destroyed by the hand of Teddy Boys, through Beatlemania, to hippie events and festivals, in which freedom was expressed less aggressively, through nudism, drugs and generalised spontaneity” (Hebdige, 2004, p. 216).

When focusing our attention on the analysis of youth cultures within a contemporary context, the emphasis is necessarily on the daily activities in which young people are involved. It is from the observation and analysis of these activities that several authors have concluded that young people tend to develop and engage in various risk behaviours (Vuolo & Uggen, 2005; Vuolo et al., 2013; Primack et al., 2008; Mulder et al., 2009; Mulder et al., 2010; Guerra et al., 2016). Authors such as Shapiro (2003) have focused their research on understanding how the development of popular music itself has brought new trends in drug use. Today, individuals seem to be more predisposed to appreciate certain types of music and to identify with specific musical genres, based on their own substance use habits. When the identification with one or more music cultures occurs, individuals tend to internalise and share the values and activities associated with it. Consequently, these values or activities may include positive or negative definitions about drug use, resulting in initiation and/or cessation, or even in an increase or decrease in their consumption (Becker, 1963). Within this framework Vuolo et al. (2013) argue that young people construct their identities around a musical micro culture(s), based on the norms and values shared by these networks, plural youth cultures define the acceptance of group practices as normal and pleasant or as deviant and unpleasant.

According to Hall et al. (2013), musical references to the use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs use have been increasing in popular music and one justification is the growing popularity of certain music genres. Mulder et al. (2010) conclude that in young people's preferences for ‘heavy’ music in particular, it has been a trend towards the consumption of psychotropic substances by ‘heavy’ music fans. Also according to Vuolo and Uggen (2005), the greater the listening to rock music, the greater seems to be the tendency to use these substances (McNamara & Ballard, 1999; Singer et al., 1993). From fans to musicians, Miller and Quigley (2011) determined that licit and illicit substance use is positively associated with rebellious/intense genres such as rock music.

Equally central to the approach to risk behaviour is sexual activity. Authors such as Christenson and Roberts (1998) claim that from the sixties to the present, sex has increasingly permeated popular music, since this type of music is particularly common among young people who are initially attracted to the sexual intensity of the music and lyrics (Arnett, 2002). Kalof (1993) also mentions that the sexual images of many songs are quite intense and that sexual activity has been identified as the most frequent motivation/association in relation to references to alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use in popular music (Hall et al., 2013). Therefore, ‘one aspect of rock music that has always been taken for granted by its proselytes and detractors alike is that it is a form of music that somehow means sex’ (Frith & Goodwin, 1990, p. 315). Rock music thus embodies the problems of puberty, supports, and articulates the psychological and physical tensions of adolescence, while it accompanies the moment when adolescents apprehend their repertoire of public sexual behaviour (Frith & McRobbie, 1978). Cohen (2001) suggests that rock artists construct scripts of sexual consumption and practices, and transmit patterns of expectations for the sexual and psychotropic behaviour of men and women. Thus, rock stars end up assuming a protagonist role, through their behaviours and performances, namely through movement adopted and through dance. These types of choreographies used to bring movements that incite the practice of free and independent sex, and the pursuit of pleasure by women and men in unconventional ways to the center of the pop-rock music scene (Carvalho, 2016). Therefore,

“(…) from our point of view, it is impossible to ignore the correlation between music and sex because, being so incredibly rhythmic, music has a deep connection with sex, with the rhythm of sex, with the rhythm of the heart beating, and with the movements of sexual intercourse, which is what you feel when you listen to it. We have tried to make our music provoke a reaction in people” (Flea cit. by Blanning, 2011, p. 331).

So far, it is clear that, from an early age, music has become an aspect of importance in youth culture (Mulder et al., 2009), and that teenagers have a significant role in the study of these behaviours. We can assume that music reflects the main events that concern youth experiences, namely the ones related to practices and consumption (Vuolo et al., 2013; Calado, 2007). The enumerations to this type of themes in the lyrics and videos of artists or bands are countless (namely in: Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds - The Beatles; Brown Sugar - The Rolling Stones; Needle And The Damage Done - Neil Young; Light My Fire - The Doors...) (Martins, 2019). Furthermore, the potential influence of music and pop stars is such that musicians themselves seem to be a population often stereotypically associated with a wide variety of substance abuse behaviours (Miller & Quigley, 2011) and arbitrary sex. In this regard, Ian Inglis (2007) has been developing a reflection about musical icons and their relationship with excessive drug consumption. Inglis (2007) links these behaviours to the unremitting fascination with the incredible stories of rock and roll excesses, its bohemian life, and the refusal of convention in behaviour, and the adoption of the ‘sex drugs and rock and roll’ philosophy (Inglis, 2007). Indeed, we are forced to assume that ‘these legends and narratives are crucial in the everyday lives of fans, particularly young people, and their search for positioning in the face of the authenticity and freedom of the rocker way of life’ (Martins, 2019, p. 315-316).

‘Sex, drugs and rock'n'roll' in Portugal

In Portugal, the history of psychoactivity dates to the sixties, a time of student demonstrations and new ways of being and living. According to Costa (2007), in the 1960s, it was already possible to observe the concern of the power structure regarding this phenomenon. Quintas (1997) verifies in the same period the formation of youth groups, inspired by the hippie movement. These groups assume drug use as one of their identity traits. Likewise, Ribeiro (1999) states that the consumption of certain substances dates to the beginning of the Colonial War. However, in Portugal, ‘until the beginning of the seventies, drugs did not constitute neither a collective reference, nor a social problem’ (Marques, 2008, p. 46). Thus, only in the early 1970s can we find the first political manifestations regarding drugs (Monteiro, 2013), since “in Portugal, the 1970s were the expression of deep political-institutional, economic, and socio-cultural changes that became essential references to the characterisation of the drug phenomenon in the country” (Dias, 2007, p. 34).

The first major edition of the Vilar de Mouros Festival happened in 1971, considered the oldest in the country. It was also here that the first collective demonstration of illicit substance use in Portugal took place (Poiares, 1995; Ribeiro, 1999; Marques, 2008). In the same year, the first national campaign against drugs was launched, which included the subsequently famous slogan ‘Droga-Loucura-Morte [Drugs-Madness-Death]’ (Monteiro, 2013). This campaign had as its main objective the display of posters, mostly in the city of Lisbon (the capital), which showed a skull on a black background, and the initials of the well-known substance LSD (Poiares, 1995). However, this campaign ended up not producing the desired effects of social unease about the drug problem in Portuguese society (Agra, 1995) and even ended up awakening young people's interest in the consumption of this type of substance (Fernandes, 1993).

Later, in the period following the April Revolution3, the return of the ex-colonies to mainland Portugal brought with it the practice of consuming certain substances, including liamba4, and consumption leapt from the private sphere to become public (Quintas, 1997). After the fall of the regime, the country finally opened freely to popular culture, namely cinema, literature, and music. This provided a wide range of articles that dealt with issues of intimacy and relationships, once forbidden by censorship, and had evident repercussions in the way some individuals now experienced their sexuality (Neves, 2013). These new patterns of freedom and sexual experiences were also linked to the revolutionary character of emerging youth cultures, influenced by Anglo-Saxon rock music and by the lifestyles transmitted by them.

Since this cultural opening, free sex practices and psychotropic consumption have remained present in Portuguese society, and currently, the consumption of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco has been intensifying since 2012 (Antena 1, 2017). Nowadays, Portuguese young people continue to consume legal and illegal substances, and this trend is particularly visible in the public domain in leisure spaces linked to music. Every year there are numerous arrests for trafficking and possession of illicit substances in music festivals (Correio da Manhã, 2017; TVI24, 2017; Jornal de Notícias, 2017; SIC Notícias, 201). It is also in these spaces linked to music that sexual practices tend to be more frequent (Público, 2017).

Methodology

To carry out an analysis on the evolution of practices and representations of licit and illicit substance use and attitudes towards sexual practices in Portugal, from 1960 to 2015, we tried to develop an identifiable mapping of routines and consumption, which would allow us to highlight the appropriations and recreations of those involved in the professional sphere of Portuguese rock music. Having as a premise that the social context is a complex field, involving countless representations and interactions, we tried to approach reality from a set of possible readings (Guerra, 2010). To this end, we focused on the protagonists of Portuguese rock music, by conducting fifty semi-structured interviews with crucial actors of the rock sub-field of our country, to understand the social meanings underlying the narratives of these agents.

In this context, this task was carried out between March and August 2018, in person at various spaces and locations in the country, and prior contact/scheduling was mainly done through email, phone, and/or social networks. The actors who gave voice to the semi-structured interviews were selected using non-probability purposive sampling, commonly referred to as convenience sampling (Agresti & Finlay, 2012), to allow a direct approach to individuals who circulated and still circulate within the Portuguese rock sphere. These in-depth interviews thus enabled us to obtain data of a subjective nature, such as beliefs, feelings, thoughts, and attitudes, among others, which are essential for the understanding of the universes of meaning of the subjects. To obtain not only an overview of the extensive corpus collected, but also an in-depth analysis of particular cases, we used the content analysis technique, including quantitative and qualitative indicators. On the one hand, we focused on the interpretation of the interviewees' observations (Elo et al., 2014) and the meanings they attribute to their individual actions; but also on the identification and quantification of relevant themes in the individuals' perspectives, to find common structuring elements of their actions. To inform, respect, and guarantee the rights of participants, who voluntarily agreed to collaborate with this research, we thought it essential to develop informed consents within the scope of the interviews5, taking into consideration the rules of the Code of Ethics currently in force in the Portuguese Sociological Association (APS)6. In addition, we have submitted this project to the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Sociology of the University of Porto for review, and informed consents for all stakeholders have complied with current regulations on the protection of personal data.

A more male, more urban, and more educated population

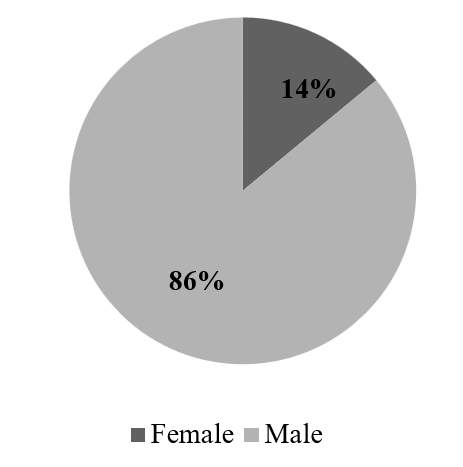

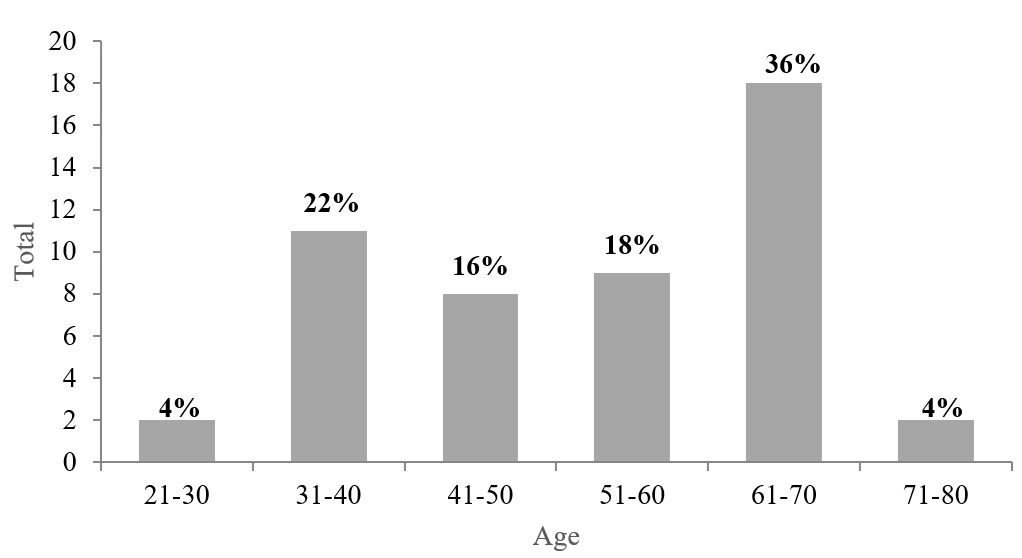

A summary of the main sociographic characteristics of the interviewees is presented in the Figures below. In general, our sample proved to be heterogeneous, from the point of view that we interviewed men and women, but not equally distributed. We interviewed 43 men and seven women7, as we can see in Figure 1. This is in line with a reading of gender within the global space of rock, which in our country tends to be almost exclusively male, particularly in the senior generations. The interviewees’ ages range from 29 to 78, with the 61 to 70 age group being the largest (18 respondents), followed by the 31 to 40 age group (11 respondents), as displayed in Figure 2. Making a general reading, we can state that, in terms of age, this is a group where the 60s age group is prevalent, followed closely by the 30s age group.

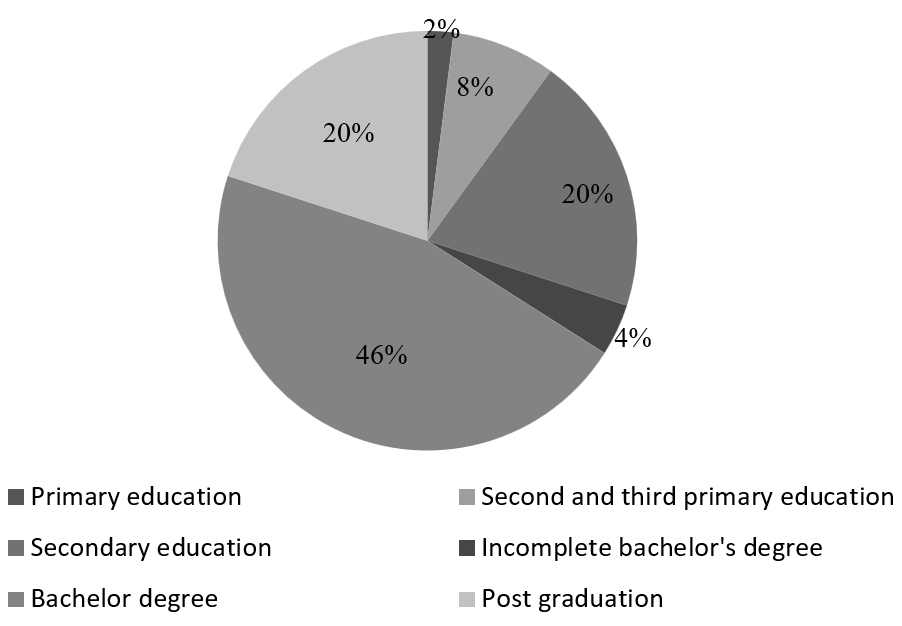

This is a professionally integrated group with different professions and/or hobbies related to music and the creative industries. They are also highly educated individuals (see Figure 3). 23 out of the 50 interviewees have higher education, and 10 have masters and/or postgraduate degrees. They all have different lifestyles but share certain aspects. Considering the generality of the Portuguese population, we are facing a group of social agents mostly highly qualified from an academic, professional, and social point of view.

Well-measured risks

Embedded in the festive logic and celebration of hedonistic values (Pais, 2003), the incessant search for sensations and experiences often ends up involving psychotropic consumption, which sometimes results in excessive and/or addictive practices. In this sense, historically, rock and rock stars have often been associated with abusive behaviours of substance use and irresponsible sex (Grossberg, 1993). In fact, according to Miller and Quigley (2011), substance use is associated with more rebellious/intense musical genres, such as rock music, and this premise applies not only to fans but also to musicians and other agents who participate in the rock scene. In this context, Ian Inglis (2007) has reflected on rock stars and their relation to drug use. Therefore, based on these premises, it was fundamental for us to try to understand its applicability to the contemporary Portuguese rock scene, namely looking at the consumption and practices of its main protagonists. Thus, analysing the consumption habits of both legal and illegal substances of our interviewees, we found different habits, ranging from simple experimentation, recreational consumption to addictive consumption. Regarding legal substances, namely tobacco and alcohol, besides moderate or social consumption, some interviewees confessed to drinking or having drunk too much in certain situations, such as specific events or contexts, ending up harming their performances on stage or at different points in their career (age or professional phases). The same happens with tobacco, described by some of the interviewees as the biggest addiction they have ever had and the one that was most difficult to quit.

After the shows, there are people there who want to meet the artist and they ask ‘what do you want to drink?’ and what most people drank was wine (bottle wine, good wine), beer or whiskey and we drank, but not because of alcoholism. I had liver surgery because of alcohol and from then on, I never played again. Tobacco also harmed me, I smoked a lot, there were up to three packets of cigarettes a day, but then I never smoked again. (Vicente, 78 years old, musician)

It has always been a good relationship, I have never had any problems, neither with legal nor illegal drugs, I am not prone to addictions. My only addiction was tobacco, but I got rid of it easily from one day to the next, despite having smoked for thirty years. (Alfredo, 58 years old, musician)

I think some legal ones are worse than the illegal ones; I think tobacco kills a lot more than some illegal drugs in Portugal. I smoked when I was still in high school, I started smoking just for the music and I smoked, I think about 5/6 years, but I smoked almost three packs a day. Now, sometimes I smoke at a party or something, but I'm not addicted. As for alcohol, I only drink three drinks: water, wine (which is good) and black beer. (Cláudio, 67 years old, radio broadcaster)

About the interviewees' habits of consuming illegal substances, we found different experiences and histories: from individuals who have never consumed; to some who have experimented; to others who use or consume socially; to individuals who recreationally use with some frequency; to others who use or have used daily; and even to people who confess to already having been dependent on one of these substances. We also have - although few - some interviewees who confess to having already experimented all or almost all the substances they know from a scientific point of view, in order to know the effects of each one of them. It should be noted that only one of the interviewees used the word ‘drug addiction’ to classify his history of previous addictive consumption and admitted having done medical rehabilitation to treat his dependency. Of the remaining respondents who admitted to having had addictive consumption in certain periods of their lives, none of them used this term to describe it.

I had a phase in my life when I experimented almost all illegal substances, that I remember, the only thing I never felt any appetite for was syringes and heroin and drugs of that weight, everything else, from cocaine backwards, I experimented to see what it was like, from LSD, acids, psilocybin, mescaline, hashish, weed, marijuana... that which is normal. I did all those experiments when I was 20/21 years old, (...) but it was the daily life of musicians. (Tiago, 66 years old, musician)

Now, I think I only have legal substances in my life, but there were times in the past when I had some illegal ones, yes. At school, like all kids, I guess, it's almost inevitable. And, then I had another phase in my life where yes, I dealt more with illegal substances and I had a period, but in that case, it was a heavier scene like that, and if I didn't become a drug addict then (and I'm talking specifically about heroin), I don't think it will ever happen. (Nelson, 48 years old, radio broadcaster)

Then, a few years later, I had a boyfriend who gave me a try. As I wasn't 18 at the time (I was already in my thirties), I thought I could experiment, and it was a mistake that cost me dearly and could have cost me even more. I lost a lot of things, I lost focus and my career was a bit shaken and a bit on the back burner because of that situation, because afterwards you move away from people, it's a kind of morphine. (Luísa, 61 years old, musician)

Social representations in connection to society

Some interviewees confess to having had some experiences with excesses associated with psychotropic consumption, which have been harmful to their or others’ physical and mental health. In this context, they also remember unfortunate situations that happened with friends and/or acquaintances. At this point, it is important to mention some situations of excess that ended up being fatal for several international rock stars, namely for those who belong to what later became known as the Club of 27, which includes young musicians who died suddenly (particularly due to overdoses) at the age of 278.

Like all young people, I smoked and took some drugs, but I was fortunate enough to have very harmful effects, namely terrible anxieties. And there was a time when I almost threw myself out of a window, because I thought I was a bird, and my older brother held me down. They were very worried and I went into a deep crisis of great sadness, and in the meantime, I went for treatment. I had friends who got addicted to it and were practically lost, some lost their lives and others lost their ability to work. And then recovery is very difficult. (César, 71 years old, musician)

I tried to experiment almost everything, I was very reluctant about injecting products, and also because of the dangers that I recognized on various levels, so I never used them. But in my experience, I used smoked heroin and for over a year and a half, I used cocaine assiduously, because it was the only way I could stay on my feet. I had a year and a half touring almost constantly in Spain and the group was running on cocaine and other substances. One died as a result of that and others were seriously affected by that kind of substance. (Samuel, 63 years old, musician)

I had several friends who went from heroin to coke, but I confess that never for the so-called hard drugs. I was always a little afraid, because there were cases of guys who went and then didn't come back, and I didn't want to take the risk. Yes, I did smoke weed, once in a while, and it didn't do me any harm, and today, if I see one in front of me, I won't say no. The artists' world has always been a place where some things like that have always happened and they still do. (Vasco, 60 years old, journalist)

In general, some of our interviewees associate psychotropic consumption, or its intensification, with the rock universe and the contexts in which it takes place: nightlife contexts (Nofre & Eldridge, 2018), constant travelling, tiredness, feelings of loneliness, environments in which consumption is strongly present in the people around them, ways of dealing with possible social pressure on their work, among other factors. Some even argue that rock music is associated with certain substances, just as other musical genres are associated with others, which is in line with the theories already mentioned, such as that of Arnett (1991), who believes that certain types of music have different results in individuals, namely considering drug consumption, an idea also shared by other authors such as Vuolo and Uggen (2005), who argue that there are specific substances associated with certain types of music.

I think that, above all, there is one thing that is associated with artists and musicians, which is this thing of experimentation, experiencing emotions. And so, I also experimented drugs, obviously, and I felt that was part of the discovery. (Artur, 57 years old, musician)

I'm not much of a drug person and never have been; of course in this environment you have much easier access to all that quantity. It's not even in this environment, but in the life of the nightlife, the later you go to bed, the sooner you have access. But if a person has a head, I don't consider myself an outlaw in that sense, my head is in the right place. (Fernando, 38 years old, musician)

There are music genres associated with substances, which have to do with a long tradition of experiments, of experimentation, which seems natural to me. If we talk about psychedelic rock, for example, the very definition of the genre comes from a series of experiments carried out in the sixties. The use of marijuana in reggae is something that makes perfect sense because we become more relaxed and more inclined to listen to that kind of music, just like the stimulants in other faster music genres. So, I see the drug almost as enhancing the experience of the music. (Duarte, 36 years old, cultural planner)

As we have already seen and explored, one of the central points of this research is the application of the myth ‘sex, drugs and rock'n'roll’ to the Portuguese social reality. Therefore, we found it enriching to ask the interviewees this question directly, in order to cross their answers with the detailed facts they gave us throughout the interviews and verify whether or not there is a correspondence in their lines of thought.

In general, opinions are divided since 50% of the interviewees (25 individuals) responded that they consider it to be or to have been a reality, justifying their answers with examples in the first or third person. However, 10 respondents answered directly that it is and/or was a myth. Regarding the respondents who stated that it was and/or is a reality in Portugal, all or almost all emphasized that it happened on the scale of our country, in a smaller scale than the Anglo-American phenomenon. In this regard, it is important to mention that it was since the 1980s that substance use spread to different layers of the population and different age groups (Fernandes, 1993). Some interviewees even claim to have personally experienced this reality and others give examples of musicians who have.

On the other hand, among the interviewees who affirmed that this is a myth, the justification is related to the small number of individuals who have experienced or continue to experience this lifestyle in Portugal. In other words, they consider that the few people who have lived and/or live this motto are not significant for us to apply it to our country. They claimed that it is also a dated expression, which marked a specific social and historical period, namely the sixties in the Anglo-Saxon world and the eighties in Portugal, and that nowadays it no longer makes any sense. Before that period, according to their considerations, substance use in Portugal was an isolated and insignificant experience (Costa, 2007; Quintas, 1997; Ribeiro, 1999; Marques, 2008). They also mention that it is not a practice associated with the rock scene, but with the nightlife culture (Nofre & Eldridge, 2018).

The stereotype of sex, drugs and rock is not a stereotype, it was experienced, there are people who live according to that bible, some in a stronger way, others in a more consolidated way, but it is a reality. Now, it may not have as much expression here as it had in the sixties in New York or in England, which are the most glaring examples of this philosophy, but it still exists and it is something that I strongly believe, and I hope, will continue to be perpetuated. (Guilherme, 38 years old, cultural planner)

I think that term sounds good, but it is not representative. I know musicians who like drugs and others who don't, some are very sexual, and others are not. I think this is just a literary expression that can be applied to any activity and that can mean a party, a night of excess and not necessarily in that order. (Alberto, 58 years old, radio broadcaster)

I think it was a myth; everyone took advantage of the term ‘sex, drugs and rock'n'roll’ to join it and each in their own way made their own term. I think the drug problem was very serious in Portugal and it still is, but it was also serious in other parts of the world. Here it was a big shock, because we weren't used to it, it was taboo, like many other things. And, unfortunately, most of the people who joined in were lower-class people. They didn't want to know anything about school, and they turned to drugs and many died (...). (Leonardo, 67 years old, radio broadcaster)

It should be noted that the interviewees also refer to generational differences in drug use, i.e., they reckon it is a more visible reality since the 1980s in our country. Before that period, according to their considerations, illicit consumption in Portugal was an occasional and insignificant act and/or experience, compared to what was happening in the Anglo-Saxon context at the same time, a position also corroborated by national authors such as Costa (2007), Quintas (1997), Ribeiro (1999) or Marques (2008). Furthermore, our country's backwardness concerning the western world often resulted in a delay in access not only to goods but also to trends and ideologies. Therefore, all the experiences and beliefs associated with the sixties on the international arena ended up being experienced in Portugal in the eighties.

I think it was a reality, mainly in drugs, but one envolving people from the 80s/90s/2000s because in the 60s it didn't exist. Abroad it did and it's been proven that a lot of the big singers, including the Beatles, most of those guys got it right, so on the Rolling Stones you don't even want to know. (Vicente, 78 years old, musician)

I would say both things. There was sex in those years, especially in the eighties, as there always was. And there were more drugs than there had been before, because before the 25th of April there were practically none. But, compared to what was happening abroad, here everything arrived much later. What was happening here in the eighties, had already happened in the sixties in other countries. (Vasco, 60 years old, journalist)

I think there is always that magic, but in the seventies, eighties, and some years in the nineties, I think it was more real than it is nowadays. But, of course, there are always people who have much more energy, much more willingness and availability for this and these things naturally happen. I think it existed, but nowadays people are much more enlightened about drugs, the relationship with drugs is quite different, but I don't know if nowadays it is justifiable to think of a musician as madness, drugs, sex and rock'n'roll. (Rute, 37 years, musician)

Another central axis for this research is related to the processes of social stigmatization associated with rock culture and its lifestyles. Since the sixties, rock music has carried several stereotypes associated with its consumption, sexual practices, appearance, among other aspects (Encarnação, 2019), which ended up having repercussions on the ways in which rock stars are perceived by society in general. For this reason, we considered it crucial to explore issues related to the family position of our interviewees regarding their professional attachment to music. Especially because many of the interviewees started their careers several decades ago, when Portugal was still a strongly conservative country, and music was often looked down upon and considered an unsafe or unpromising professional future. In this sense, in the case of those interviewees who experienced family disapproval, this will have happened mainly at the first phase, with the family later accepting the interviewee's decision. On the other hand, some interviewees always had family support, which often translated into encouragement through investment in musical instruments, musical education, or the space provision for rehearsals and/or training.

A lot, because I was leaving the right and safe profession, as my father used to say. I had a hard time, and I don't think I could convince him. I only convinced my father much later, when I was sure that my father believed I could live my life. (André, 63 years old, musician)

As for family, I had total support. My mother’s wish was for me to be a musician. Probably even before she knew I wanted to be a musician. My family has always supported me 200%. The day I had the conversation with my father and told him ‘I want to leave my studies and dedicate myself to music’, I think the only thing he said to me was ‘if that's what you want, that's what you're going to do’. So I've always had total support. (Valentim, 56 years, musician)

At first, my parents put a bit of pressure on me. But then I was going to join a famous program, which was all famous people, and it was fine, they accepted it well and so did my wife. (...) Fortunately, I belonged to a generation whose parents were open at that time. Of course, the drugs issue had a big and dark influence on the youth of that time, and people started to know what that music entailed in the magazines they read, that it was all people connected with drugs. (Leonardo, 67 years old, radio broadcaster)

In addition to family positioning, it was also fundamental to analyse the social positioning and to equally know the feelings and reactions developed by our interviewees in situations of social stigmatisation, which may have resulted in the creation and dissemination of moral panics (Cohen, 2002) within the Portuguese society. It is also important here to compare the experiences or situations of our interviewees of different ages in order to try to understand if there are changes in these contexts over time. Regarding social stigmatization, there are many reports of situations experienced by the interviewees, which include stereotypes related to the profession, to the look, or the rocker lifestyle.

The fact that I'm a musician… This girl's parents had dreams for her, that she would marry a person of the same social class and when they realized that she was dating a musician, it was the end of the world, chaos at home and she, poor thing, suffered a lot with that. I felt the prejudice because that's what it's about. I felt the prejudice of a family, in this case, because you were a musician, they wouldn't accept you, ‘this guy is a musician, he's beneath us, he's of a class we're not interested in’. (Tiago, 66 years old, musician)

Yes, in the beginning [there was stigmatization]. When I went out to the street and on the buses, I was provoked. At that time, men used to wear their hair short and with hairspray. I didn't like that, and when they saw us or someone with long hair, they would tease us and think we were homosexuals or something like that. (Álvaro, 69 years old, musician)

In the sixties/seventies, there were people that couldn't make a living from music in Portugal (except the children of rich parents). And I know some people who couldn't get a job because they were connected to rock, ‘rock was the junkies’, so I knew situations like that. (Cláudio, 67 years old, radio broadcaster)

According to the paradigm of symbolic interactionism, a reconfigured view of social interaction is exposed, particularly the triple relationship established between social norms, socialization processes and behaviours of deviation from those very norms (Martins, 2019). In this context, Becker (1963) considers the concept of the ‘outsider’, relating it to the mistrust with which individuals pointed out as deviant regard individuals who are not deviant and vice-versa. It is in this scope that many protagonists in the sphere of rock music were and tend to be judged and labelled as deviant or transgressors in relation to the established norms in Portuguese society. As we have seen, rock music is traditionally associated with a set of marginal practices, experiences, and lifestyles, which escape what is considered normal by the generality of social actors. Consequently, these kinds of labels that are applied not only to rock musicians but to the whole set of actors that move in this musical field end up becoming an evident and inherent stigma to the perception that these individuals have of themselves and to the way they build their own identities:

Yes, there were situations at the time when I would hide my hair inside my shirt. In terms of clothes, I remember when jeans came out, I got some, but there was no way I would leave the house dressed like that. I would leave the house with the trousers in a bag, go to a café and go to the bathroom to put them on and off I went. This was when I was 18. (António, 67 years old, musician)

My look was strange. Having long hair was strange. A guy wearing earrings was strange, a guy wearing trousers of several colours was strange, wearing hair dyed three colours (as I did) was strange...so, it wasn't easy. There was a time, here in Portugal, when passing by a building site or a bricklayer, with big hair and colourful trousers, you were usually met with a repertoire of all kinds, from gay to faggot, etc. (Samuel, 63 years old, musician)

I had very long hair ever since the seventies. So, I was considered a freak and I was always harassed. My first reaction from the public, let's say I was inoculated straight away, because we were very outraged, and it was quite a confrontational attitude. I remember that when we went to the beach. We used to wear shorts and, in the seventies, people thought it was very strange. I remember the comments as if it were today. It was a very conservative city in that sense, very grey and straightforward. (Rafael, 63 years old, musician).

Conclusion

It tends to be clear that popular music (Salema, 2017) frequently incorporates themes related to licit and illicit substances and expresses references to these substances (Christenson, et al., 2012). In this sense, it was significant to verify - based on our interviewees’ responses - that the (psychoactive) consumption of legal and illegal substances is also a common practice among the participants of the Portuguese rock'n'roll scene. Effectively, from fans to musicians, Miller and Quigley (2011) determined that the use of legal and illegal substances is positively associated with rebellious/intense genres, such as rock'n'roll. And in the context of Portuguese rock'n'roll over the last forty years we find different patterns of psychotropic consumption among our interviewees, whether of legal or illegal substances: ranging from simple experimentation, through recreational consumption, to actual addictive consumption. Equally central to the approach to risk behaviors is sex. Authors such as Christenson and Roberts (1998) claim that, from the 1960s to the present, sex has increasingly penetrated popular music and this type of music is particularly popular among youth (Arnett, 2002). Given the national rock'n'roll scene, we concluded that there is an emotional enchantment in relation to its actors regarding a risky, daring, heterodox sexuality, which sometimes results in an excess and subsequent trivialization of the sexual activity.

The issues inherent to the rocker lifestyle, namely related to visual appearance, substance consumption patterns and affective practices end up clashing with myths, prejudices and taboos and consequently result in processes of social stigmatisation. Many of the stereotypes felt by the Portuguese rock'n'roll actors start in the family, which tends to disapprove a lifestyle that is considered deviant (Becker, 1963), an aspect that also contributed to the fact that careers are often devalued, especially when they are surrounded by the mysticism of substance use, whether licit or illicit. At this point, we also easily realise that not only in family contexts, but in society in general, there is still the idea of not considering rock music (Oliveira, 2019) as a profession, but rather as a hobby or as a secondary activity and incapable of promoting self-sufficiency (Guerra, 2010; 2015).

In short, according to the interviewees, the myth about ‘sex, drugs and rock'n'roll’ in Portuguese society still exists, although younger generations of musicians tend to distance themselves from it. While this applies to our reality and dimension, since we didn't have - nor do we have - musicians with the available resources to live intensely the style and life of international rock stars, we also heard about excesses in the world of rock'n'roll to the point that some people lost their lives and careers as a result. We have also had participants in this post-subculture who have become addicted to certain substances at some time or during their entire lives. However, there is no doubt that, deep down, we are still a country with a conservative character, in which musicians and people linked to the arts, in general, tend to represent the invisible fringes of society, as if music or any other artistic expression did not form a legitimate source of income. In this specific case, musicians and other actors of the rock'n'roll scene, besides having precarious and uncertain professions, continue to be marginalized in Portuguese society, also due to their often more alternative looks (which may include tattoos, unusual hairstyles, diverse clothing, unusual accessories, etc.) and their presumed consumption. We know that we are a society marked by rapid but late development, full of contradictions. However, transformations in everyday contexts are already visible throughout the analysis among interviewees of different age groups and residents in metropolitan areas. We can only hope, then, that the social evolutions continue to develop and be reflected, subsequently, in an effective change of mentalities and representations regarding rock'n'roll and its lifestyles in Portugal.