Questioning the canonical perspectives on the post-war Italian cities

The canonical planning and historiographical perspectives concerning the Italian cities in the second post-war period describe their complex and layered process of modernization, growth, and expansion mainly as the result of linear series of planning acts and policies. Consolidated interpretative accounts include a city planning reading through the sequence of City Plans (Oliva, 2022; Morandi, 2007), as well as an urban history centred on the notion of the public city (Infussi, 2011); the public housing estates - and the leading national programmes they have been generated by - are the main objects of the historiography (Di Biagi, 2001; Irace, 2008), together with iconic private interventions linked with experimental solutions and outstanding clients which are widely described but not as extensively diffused.

The article aims at questioning this understanding of the role played by the public powers, discussing their relationship with the private actors in the articulation of the urban landscape. The reading of the administrative documents of planning agreements through the methodological lens of micro-history calls for a reconsideration of the prominent role of state and municipal entities and of the central planning legislation (Revel, 1989). It opens to an interpretation of the architectural and planning history of post-war Italian cities that is neither linear nor merely technical; it unveils a nuanced relationship between public and private sectors, originating a variety and stratification of urban objects, resulting from a plurality of policies and cultural, disciplinary, administrative, and professional positions that produced a significant part of the post-war built stock, overlooked mainly as a product of low-quality and quantitatively oriented private estate processes in the peripheries (Caramellino & De Togni, 2022).

Planning agreements: a profile of the tool

In the Italian legislative context, planning agreements are long-standing arrangements between the public administration and public or private actors, aiming at organizing and disciplining expertise and goods for planning purposes, through which the involved operators define the mutual obligations.

Used since the end of the nineteenth century, these agreements remained confusing tools until the amendments introduced in 1967 by the integration (Law n.765/1967) to the national Planning Law of 1942, which formally legitimised their existence for the first time.

Their use until then had been discussed mainly from the point of view of jurisprudence and administrative law: several bibliographical sources (D'Elia, 1968; Mazzarelli, 1975, 1976, 1979; Marocco & Picco, 1978; Centofanti, Centofanti, & Favagrossa, 2012) testify to the clear pre-eminence of an analytical and critical approach giving rise to a debate centred on the definition of the authoritative or consensual nature and the implementation possibilities of the instrument rather than on its role in the construction of the city, intending to trace its profile and application boundaries in the absence of a precise definition from the legislative point of view.

The legislative and planning discussion on the subject has always seen the defence of private initiative and the protection of public interests in confrontation, centring on the issue of the legitimacy of recurring to private legal acts for purposes of public relevance. In fact, agreements were often contracts based on the civil law principle of the exchange of services, in some cases leading to direct gains for the private parties even though they were based on the public importance of the operations: until the end of the 19th century - when there was not a clear separation between public and private law sectors in the administrative activities yet - no problems of legitimacy emerged; in the first fifteen years of the 20th century, in the context of a policy of greater control over speculation, the regulatory and programmatic aspects were accentuated, and the explicit reference to the relationship with the City Plan became widespread; between 1915 and the 1930s, in a phase of rapid and disorderly urbanization and of a strong need for private intervention by the public sector, the direct link between conventions and regulatory plans, which in the meantime had increased their programmatic content, often disappeared (Mazzarelli, 1975, 1976, 1979; Erba, 1978).

With the Planning Law 1150/1942 - the first effective national regulation of the sector - the role of private parties in the implementation of planning tools was finally regulated. Still, it was only with the amendments introduced by the Law 765/1967 that we began to speak explicitly of planning agreements including them in the public discipline of building and planning activities: they are framed as the required tool for municipalities to issue building authorizations in the absence of a Detailed Plan, for allotment and building proposals in conformity with the provisions of the City Plan. With the legislative reforms that followed from the 1960s onwards, the doctrine and jurisprudence of agreements became more easily framed among the urban planning instruments, with allotment and public housing agreements.

In the 1950s and 1960s, during the period of reconstruction, at first, followed by further building and economic boom, the widespread recourse to agreements in place of the Detailed Plans - which were the regular tools foreseen by the General City Plan to define its implementation details, area by area - had particularly significant effects, albeit with different outcomes, on the development and expansion of Italian cities. Agreements broke in the urban planning debate, being increasingly interpreted as a tool of speculation and alteration of planning policies by private actors (Boatti, 1986; Canevari, 1986; Campos Venuti, 1986a, 1986b; Campos Venuti & Oliva, 1993) to overcome the complexity of the procedures and the limits foreseen in the post-war City Plans. The relationship between agreements and City Plans was questioned, in the framework of a functional approach to the spatial disciplines based on the faith in a linear and continuous growth of the city, particularly concerning the construction of the expansion areas.

More recent research initiatives, deepening the historiographical analysis and addressing a significant number of planning agreements’ documents (De Togni, 2015) while considering the impact of negotiation processes on the built city (Zanfi, 2013), investigate instead how planning agreements reflect a stratified experience of punctual negotiation, offering a privileged lens to observe tools and practices, professional and administrative networks, demands for social emancipation and renewal of planning processes, at the centre of a complex system of actors, habits, disciplinary and critical positions. They often facilitated the implementation of the City Plans through direct and friendly execution, defining building density constraints, distances, green areas, welfare infrastructures, and services before the introduction of standards. From the perspective of micro-history, they question the more immediate and intuitive notions linked to a linear reading of the planning process, which are not necessarily appropriate to describe the complexity of the urban landscape structuring.

Precisely because they have long been instruments that were not clearly framed by legislation, they offer an interesting insight into the economic and political power relations between the public and the private sector and the interweaving of entrepreneurial strategies, design cultures, and regulation, administrative and bureaucratic organization. They can lead to a reinterpretation of cultural and professional backgrounds and social and negotiation processes, which is crucial for a complex reading of the post-war Italian cities.

Milan: the economic capital of Italy at the core of the post-war debate on planning agreements

The post-World War II period in Italy was characterized by an intense debate on the objectives, limits, and tools of architecture and planning, which shaped the reconstruction and expansion of cities and influenced their representation and perception. The building sector and the land market became crucial in the national development (Bianchetti, 1993; Piccinato, 2010), confronted with unprecedented quantities and rhythms, and at the same time intercepting the aspirations of the professionals in the sector for a quality reconstruction and a renewal of the discipline in a modern sense (Rogers, 1946; Mioni, Negri & Zaninelli, 1994; Zucconi, 1998).

Milan was in that period the fastest growing real estate market in Italy, thanks to a strong demand linked to internal migration towards the country’s economic capital. In particular, a middle class of office workers and professionals emerged, attracted by the strengthening of the commercial, financial, and management pole, calling for renewed forms and typologies to respond to a precise demand for quality and services, which codified a series of housing models that would influence the following decades (Petrillo, 1992; Irace, 1996; Lanzani, 1996; Foot, 2001; Zanfi, 2013).

From the end of the War, Milan also embodied the great expectations associated with the first implementation in a large city of the new 1942 Planning Law, which defined the instrument of the General City Plan and made it compulsory throughout the country. The Milanese General City Plan of 1953 was the main occasion for the discussion of the new planning tools (Barbiano di Belgiojoso, 1955; Bottoni, 1955, 1956; Edallo, 1955, 1956; Albini et al, 1956; Astengo, 1956; Piccinato, 1956). Over two decades, the broad historical-critical debate on its genesis and consequences constituted the origin of a historiographic position that over time has reduced the significance and relevance of planning agreements to a simple instrument of speculation and disruption of planning policies, in “an entirely private plan conceived according to the needs of the real estate regime” (Boatti, 1986, p. 43), giving rise to and consolidating a vision of the city as an exemplary case of the failure of modern planning ideals and the triumph of speculation (Tintori, 1958; Vercelloni, 1961; Portoghesi & Vercelloni, 1969; Vercelloni, 1969; Graziosi & Viganò, 1970; Patetta, 1973; Tortoreto, 1977; Zucconi, 1993) without adequately verifying the actual conditions of application in the period under study and the real consequences. By relating the main findings in the literature with the disciplinary and regulatory context in which they were produced, the influence of the post-war features of agreements emerges on evaluations that are then extended to other periods and regulatory contexts: we can, for example, see how the critical position linked to the preliminary agreements introduced by the Law 765/1967 and its widespread use as a means of negotiation in the private implementation of the following decade influenced the consideration of the instrument as a whole (De Togni, 2017).

For these reasons of political and disciplinary relevance, Milan has thus become the main case study for the planning literature focusing on the use of planning agreements in the development of post-war Italian cities (Balducci, 1984; Oliva, 2002; Gaeta, 2007; Zanfi, 2013). The main contributions interweave the theme with broader issues relating to the limits and potential of the urban planning discipline and the criticality of the professional world, and mainly deal with the topic in relation to the expansion of the city, inside and outside the municipal boundaries. A reading of the agreements insisting on the historic central area of Milan (De Togni, 2014) question a disciplinary focus that has so far given relevance to agreements mainly as instruments for the construction of the peripheral city, suggesting at the same time a use of the source as a key to reading architectural and urban projects that can be extended to the “ordinary landscape” (Caramellino & Sotgia, 2014; Caramellino & De Pieri, 2015) of Italian cities. Observing the city through this source allows for close observation of the forms of construction of the urban landscape, particularly concerning the intertwining of entrepreneurial strategies, design cultures, the residential desires and imaginaries of emerging social classes, and administrative and bureaucratic regulation and organization.

Four years of negotiation: the micro-history of Piazza della Repubblica tower

This paragraph reconstructs the negotiation concerning the construction of the Piazza della Repubblica tower1 in Milan, a mixed residential and office building for the upper-middle class in the centre of the city and one of the best-known post-war projects by the architect Giovanni Muzio.

This micro-analytical reading aims to highlight possible links between planning agreements as sources, the processes they describe and neglected horizons in the political and institutional history of planning, applying some methodologies typical of micro-history (Lombardini, Raggio & Torre, 1986).

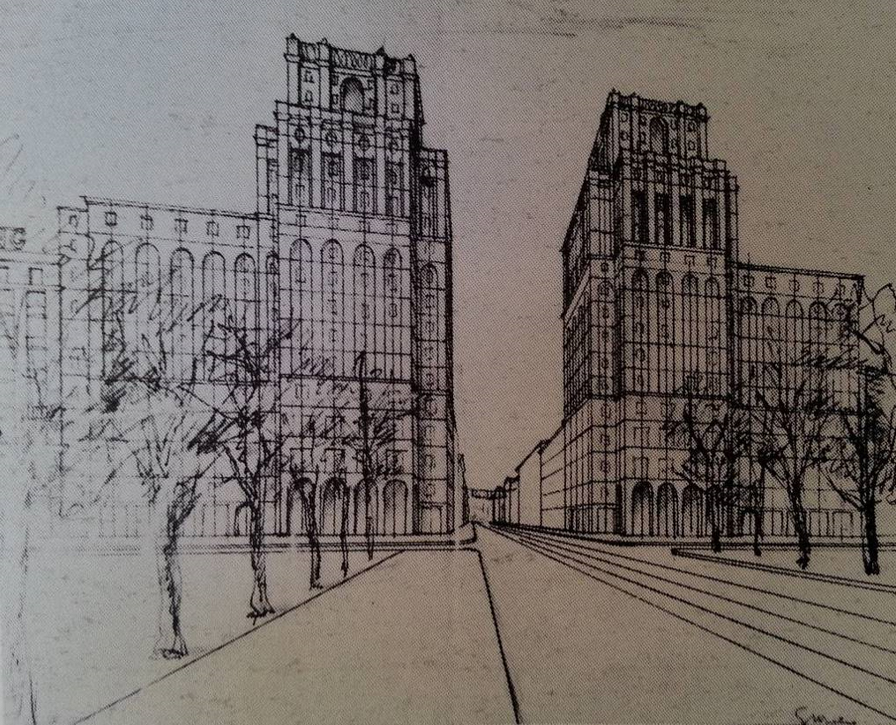

The case study area is the object of a Detailed Plan, implementing the general City Plan of 1953. The project envisaged a symmetrical arrangement of the headers of Via Turati on Piazza della Repubblica, through the construction of two similar tower blocks, consistent with a preliminary idea of Giovanni Muzio, who in 1924 had already proposed a solution with two identical symmetrical towers for the opening of the street towards the square (Figure 1).

Irace, 1994, p. 184

Source: Figure 1: Giovanni Muzio, Studio per i due grattacieli di piazzale Fiume, 1924

The first detailed project by Studio Muzio and the developer Reale Compagnia Italiana S.p.a. was presented in 1963. It became the subject of lengthy negotiations with the public administration that continued until 1967. The project did not respect the symmetry with the west header (the skyscraper built by Società Albergo Parco in Via Turati 29, already completed), nor the general layout indications despite its adaptability, nor the maximum height set at 60.80 metres.

While the change in plan and volume is not considered substantial, an assessment of the volumetric balance established for the two ends is necessary - exceeding the maximum height being difficult to accept. The proposal then further derogates from the Detailed Plan provisions by reducing the length of the internal body and forming a simple body along the whole southwest boundary. Still, these variations are considered secondary to the problem of excess volume, highlighting the fact that typological issues were not at the centre of the normative interests of the administration.

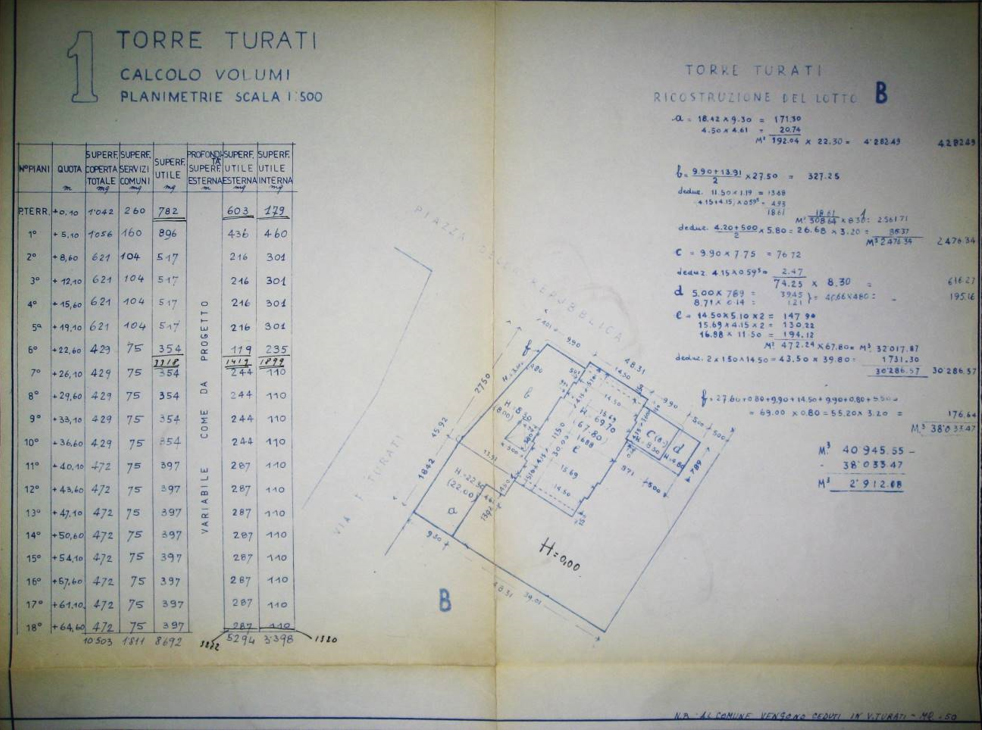

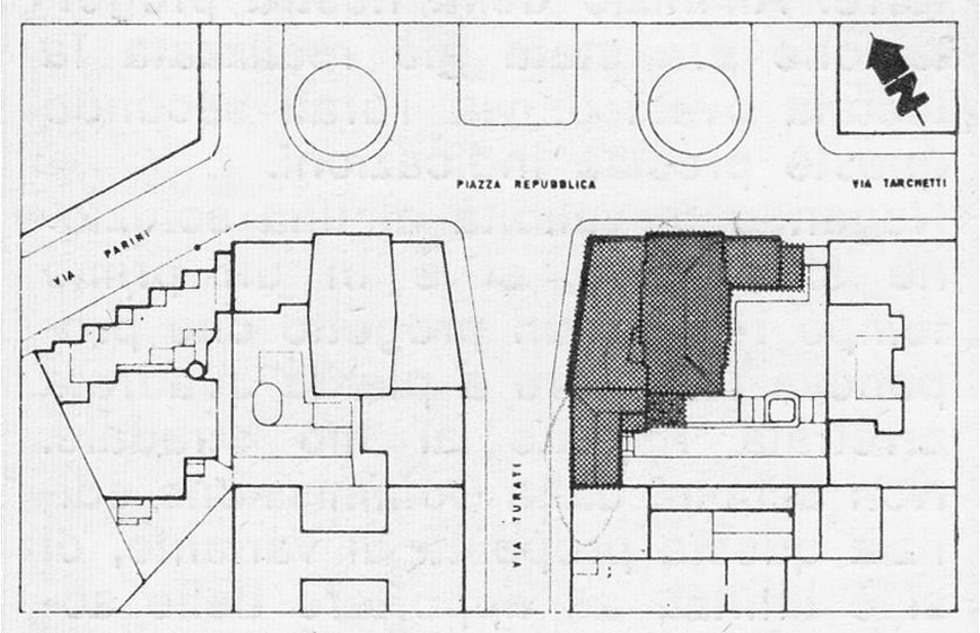

When the company was asked to revise the project, new drawings were shortly presented (Figure 2), adapting to the envisaged volumes, thus overcoming the exceptions raised by the Town Planning Office. The revision proposed a complex consisting of a nineteen-story tower building resting on a slab and a five-story body completing the front towards Via Turati (Figure 3). The hexagonal plan envisaged by the Detailed Plan, as carried out for the building at the west end (Figure 4), is modified in a stepped layout tapering towards the north and south fronts. In correspondence with these two façades, a gradual overhang reaches its maximum projection on the tenth floor, corresponding to the flat levels. The tower is defined at the top by a roof that encloses the technical volumes and reaches a maximum height of 75 metres, demonstrating that the real problem in the original project was exceeding the volume and not the maximum height or the changes to the symmetrical layout.

Comune di Milano, Archivio del Servizio Gestione Pianificazione Generale e Organizzazione Dati Urbani, folder number 14391.

Source: Figure 2: Tavola 1: “Torre Turati - Calcolo Volumi - Planimetrie scala 1:500”

Bernasconi, 1969; Gramigna & Mazza, 2001.

Source: Figure 3: Similar cut for the images of the complex in the pages of Casabella in 1969 and Milano. Un secolo di architettura milanese dal Cordusio alla Bicocca in 2001

Bernasconi, 1969.

Note: Source: Figure 4: Layout of the two headers compared on the pages of Casabella

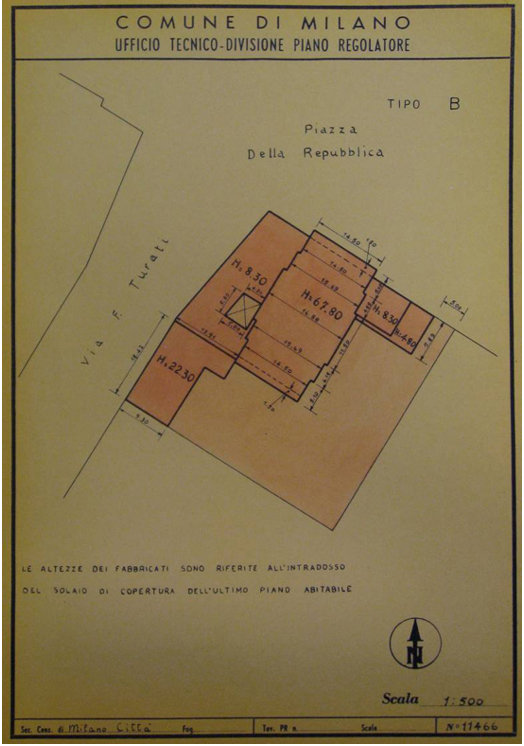

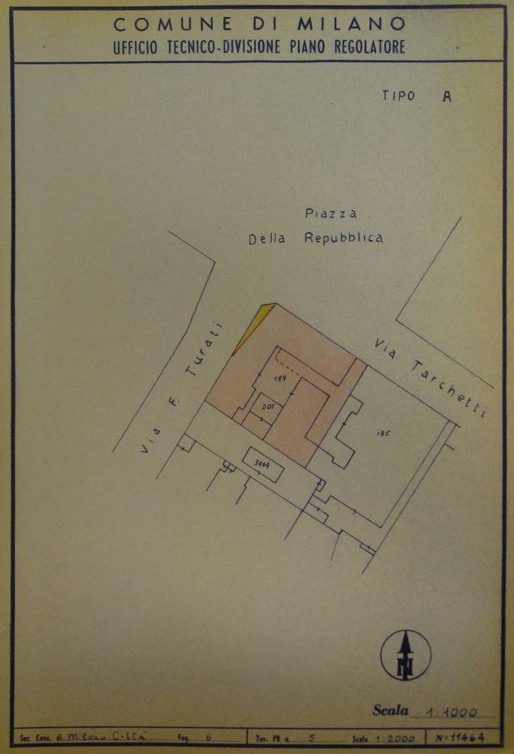

The revised project, thus respecting the maximum volume but with significant changes to the plan and volumes of the Detailed Plan, obtained the favourable opinion of the Building Commission. A proposal for an agreement was drawn up, including a plan and volume scheme approved by the Building Commission (Figure 5), which was repeatedly discussed between the parties and made official in 1967. The negotiation, including multiple and even minute aspects of the architectural intervention and discussing typological and technical aspects questioning even the provisions of the Detailed Plans, was concluded just before the 1967 legislation restricted and normed the use of planning agreements as preliminary authorization for allotments plan in the absence of the expected dedicated planning instruments.

The agreement states that no rooms or living spaces are allowed above the building heights (article 3), that “the technical volumes must be included and architecturally resolved in one floor above the height of the last living floor” (article 2), and that “the unity and harmony of the architecture of the two towers facing Piazza della Repubblica is particularly required” (article 7). The agreement also provides for the developer to transfer to the Municipality a portion of approximately 50 square metres of its own land, which is located in the roadway (Figure 6). The transfer is free of charge as it is intended to cover the contributions to the Regulatory Plan partially, even before the free provision of land needed for primary urbanization works was regulated by the Law n.765/1967.

Comune di Milano, Archivio del Servizio Gestione Pianificazione Generale e Organizzazione Dati Urbani, folder number 14391, act 146070/3761 P.R. 1961.

Source: Figure 5: Layout approved by the Building Commission and attached to the proposal for the agreement

Comune di Milano, Archivio del Servizio Gestione Pianificazione Generale e Organizzazione Dati Urbani, folder number 14391, act 146070/3761 P.R. 1961.

Note: Source: Figure 6: Scheme approved by the Building Commission and attached to the proposal for the agreement

It is interesting to note that the publications (Bernasconi, 1969; Muratore et al., 1988; Gramigna & Mazza, 2001) devoted to the building make rather misleading references to the limits imposed by the Plan and the ensuing negotiations2, which nevertheless left ample room for derogation in the evolution of the project. On the pages of Casabella in 1969, Gian Antonio Bernasconi opened his column presenting the project critically, pointing out that the tower was born with an underlying flaw due to the poor quality of the Detailed Plan, and that the layout of the two symmetrical towers meant “referring to sad languages that have fortunately expired, and jeopardising the specific outcome of the individual buildings”. He goes on emphasising how the Muzio architects, “well aware of this danger (...) tried to force the building commission to adopt a more evolved solution; not succeeding, they segmented and fragmented as much as possible (...) the stereotomy within which they were forced to act”. In the following descriptive notes (Muzio & Muzio, 1969), the architects reiterate how their first proposal, based on a square base set back from the street level, was not accepted by the Building Commission and how they were required to limit themselves to changes in volume following the plan. The same position is adopted in the file on the building published almost twenty years later in Guida all'architettura moderna: Italia. Gli ultimi trent'anni, which takes from Casabella not only the critical approach but also the iconographic apparatus. It mentions “the tricks and ploys adopted to overcome the limits of the Detailed Plan” and the square plan project “rejected by the municipality”, without any mention of the fact that the volume was exceeded and that final approval was given to a project that was in any case an exception to the provisions of the Plan.

Evidently, the emphasis given to the comments on the volumetric approach in the administrative acts and articles is quite different: in the first case, it is clearly stated that the main problem of the presented proposal is not so much the variation with respect to the planned symmetry of the headers or any typological aspect, but the exceeding of the maximum volumetry allowed both on the area as a whole and on the single lot, while the report by the designers and the presentation of the building in Casabella, clearly taken up in the Guide, suggest that the potential of the original project has been inhibited by the scheme of the Detailed Plan and by the obstinacy in pursuing the rigid symmetrical approach.

The ‘educated professionals’ at the service of the private sector, which found in Milan in the 20th century a privileged field of expression, are not directly involved in many agreements, and in the cases where this happens, they do not seem to play a particularly significant role in the negotiation, remaining almost invisible compared to the professional potential. On the other hand, the notoriety of the designers can take on a certain relevance in communicating their design intentions, arriving at a rather free interpretation of the administrative process and its limitations, as happened on the pages of Casabella, and also influencing subsequent critical and historiographical positions and the public perception of the relationship between design, the urban environment and regulatory positions.

The agreement, and the preparatory documents collected in the Archives of the General Planning Management and Urban Data Organization Service, thus constitute a unique and overlooked source of information on the negotiation between public and private actors, of a bureaucratic-administrative nature but certainly not without consequences on architectural projects and urban settings. They allow us to observe administrative nuances and design strategies that have never been dealt with, even in cases such as the ones of iconic buildings that have been studied extensively; on the other hand, they show how in these cases the added value of the proposals of the most famous and established professionals of the time had no relevance from the bureaucratic and authorization point of view.

The case of Piazza della Repubblica tower discusses the formalization of linear planning processes, incorporating underexplored actors, forms, and practices of implementation in the historical analysis, defining them through a dynamic composition of different perspectives and suggesting a tension towards plural contexts in which the circulation from the micro- to the macro-analytical level is possible (Revel, 1996). It exemplifies how the documentation collected in the agreements folders can open up new perspectives of analysis of the planning processes - highlighted in their negotiated nature - and in relation to the design processes, offering the opportunity to acquire interesting and unpublished details also concerning well-known cases and buildings that have already been historicized, allowing for a series of close observations that can interfere with large established narratives.

Conclusions

The reading of planning agreements as tools at the centre of a complex system of actors, customs of use, and disciplinary positions that well represent the daily making of the modern and contemporary city allows to discuss a consolidated interpretative framework, redefining its premises and underlining the limits of a reading of the agreements as mere instruments for the adulteration of planning policies. A first historiographical reflection suggests the overcoming of a history of the city centred on the realization of the plan forecasts and on accounts that show their fragility and instrumentality in a direct comparison with the documentary sources, opening to an exploration of the planning agreements as an opportunity for dialogue and confrontation between the actors involved in the material construction of the city. It can be placed in the perspective of an urban history based on a close observation of the forms of the urban landscape, where the protagonists actively interact with space, its construction, and its organization; it is part of an interpretation of the post-World War II city as urban setting that is born consistently from negotiation processes and not only from the direct implementation of purely prescriptive planning devices, while stressing that the very instruments of the plan demonstrate an ability to guide processes and define the possible limits of negotiations; it results from a micro-historical approach involving both the tools of analysis and the narrative strategies, exploring non-traditional sources shedding light on the processes and phenomena they incorporate, capturing recurring configurations in a documentary series linked to a specific context.

This reading is made more complex by the specific framework - characterized by a disciplinary moment in which the confidence in a new planning instrument that could frame the entire planning and implementation process was high - and the Milanese context, rich in expectations. These are the assumptions of a critical reading so strongly based on the notion of altered or failed Plan, promoted in fact by a professional world tied to a rather rigid and all-encompassing idea of Plan, which would have needed a more complex implementation also through negotiation tools.

Therefore, a new reading of planning agreements as a source for architectural and planning research is proposed. They can be analyzed as catalysts of the relations between public and private law and powers, a moment of unprecedented interaction between traditional and emerging actors (clients, professionals, administration, building companies, real estate developers) leading to a complex understanding of the layering of regulations, administrative and bureaucratic organization, entrepreneurial strategies, design cultures and inhabitants’ imageries.