Introduction

According to the World Cities Report (2016), 689 million people lived in slums or informal settlements worldwide in 1990; in 2000 there were 791 million and, in 2014 the same report estimated that 881 million people were in the same situation, representing 30% of the urban population in developing countries. In Brazil, the 2010 Demographic Census showed that approximately 6% of Brazil's population, 11.4 million people, constituting 3.2 million households, lived in informal settlements, known in Brazil as favelas (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [IBGE], 2010). According to the same survey (IBGE, 2010, p.61), there are 1,393,314 million residents in the city of Rio de Janeiro living in informal settlements or favelas, that is 22,1% of its population (figure 1). About 88% of the households living in the favelas of Brazil are located in 20 out of 36 metropolitan regions of the country (IBGE, 2010).

Favelas are often regarded as slums with pejorative overtones, yet they should be referred to as neighbourhoods with strong ties and communities which lack infrastructure and land regularisation. In fact, favelas have endured in part due to the country’s murky position on land tenure (Neuwirth, 2005). In a sense, the action of going beyond the term slum or informal settlement and naming them favelas in the early 20th century, according to Fischer (2014), was a way of not so much describing where poor people lived but rather spelling out the relationship between such places and their surroundings. This delineation, or what has been termed the “divided city” (Novaes, 2014; Vargas, 2006), has been at the heart of much of the divide within Brazilian urban centres. Yet, in Brazil, favelas are as much a part of the city as the planned city or the asfalto.

While favelas are usually subject to the same vulnerabilities of the rest of the city, such as geological issues, lack of health, and pollution, requiring a broad view of management and urban planning, they have been largely excluded in the development and design processes of the urban areas of which they are a part. They are products of needs self-(co-)produced by squatters and those marginalised by society. Historically, favelas are often devoid of basic sanitation infrastructure, accessibility to services, and adequate housing, among other easily features of the asfalto, easily recognised by people in general. Recognising them as part of the city would officially mean giving them the chance to attain levels of quality of life that correspond to those attainable in the asphalt city.

Janice Perlman (1976) begins her seminal book, The Myth of Marginality: Urban Poverty and Politics in Rio de Janeiro, with a photograph of a favela on a steep slope in Rio. The image looks dated today: wooden houses with sloping roofs of clay tiles and feel of rural life and underdevelopment. Perlman asks her readers to think about what they are seeing: a chaotic, poorly constructed, and disorderly overcrowded occupation, or a place under construction, yet to be finished, marked by a careful design and concerned with the use of very limited housing spaces and employing innovative construction strategies? For Perlman, the favela is the physical expression of a group of people battling obstacles aggravated by the absence and inconsistency of government actions, which were unable or unwilling to provide those services required for a minimum quality of life, such as sanitation, housing, urban services, among others.

By understanding the impact the favela has on Brazilian urban society, the research presented in this paper shows the evolution of the Rio de Janeiro favelas over the last 130 years and the government initiatives that have dealt with them. The main objective of this research is to examine the Favela-Bairro programme and its variants, Bairrinho and Grandes Favelas, nearly three decades after its formulation. The hypothesis is that this programme - possibly the best initiative to bring about new levels of urban infrastructure to favelas ever conducted in the history of Rio de Janeiro - had general errors and successes but conceived of new patterns of urban upgrading to the favelas. Moreover, the aforementioned programme did not follow the former governmental strategy of just removing people from their homes. A critical analysis of three favelas that benefited from the programme and its variants - Vila Canoas (Bairrinho programme), Pavão-Pavãozinho (Favela-Bairro programme), and Rio das Pedras (Grandes Favelas programme) - is put forward as part of the research, accompanied by statements from the coordinators and/or key-stakeholders of these urban projects and their retrospective perspectives.

Methods

In order to understand the characteristics of the Bairrinho programme, Favela-Bairro programme, and Grandes Favelas programme, we have carried out archival research and interviews with project team members and coordinators who developed different kinds of projects related to the three programmes presented. We have also undertaken ethnographic fieldwork in some of the favelas involved. In order to have an overview of the favelas that benefited from the public initiatives previously mentioned (Bairrinho, Favela-Bairro and Grandes Favelas), an analysis of race, income and gender has been conducted, based mainly in the 1995-2000 period. This comprised visiting the favelas and informally speaking to members of the community to learn about how the favelas had changed in both physical and psychological terms. The favelas were visited in March 2019 with the intention of returning to them in June 2019. Nevertheless, because of changes in public safety programmes, particularly the removal of military stations from the favelas, it became too dangerous to revisit Pavão-Pavãozinho and Rio das Pedras, therefore only Vila Canoas was revisited, which was in comparison a very safe favela.

Six individual formal structured interviews were conducted with major players involved in the programmes. The first thematic group of interviewees provided a nuanced understanding of the programme. They included Sérgio Magalhães1, responsible for the Favela-Bairro Programme; Adauto Lucio Cardoso2, a well-known researcher concerned with favelas; and Isais Machado, who has been five times the president of Vila Canoas Favela’s Resident Association, a Bairrinho programme recipient.

The second thematic group of interviewees included architects who worked in all three projects and who provided testimonials describing the aspects of the programmes for which they were responsible. They are Daniela Engel Aduan Javoski3; Manoel Ribeiro4; and Jorge Mario Jáuregui5.

The growth, meaning and practices of informal settlements: a transformative perspective

With the rapid expansion of urban areas, it has been clear that informal settlements are the norm rather than the anomaly for most of the developing world. For more than half a century, scholars have been studying the population increases of large urban areas and the development of housing in informal settlements, whatever the name may be - slums, tent cities, shantytowns, bidonvilles, baraccopoli, invasiones, colonias, barrios populares, barriadas, billas miseria, favelas, etc. The proportion of people living in slums or informal settlements globally rose from 23% in 2014 to 24% in 2018, growing to recently represent over 1 billion people in the world (UN, 2020). This is especially true in Latin America and much of the Global South. As a result, to paraphrase Mike Davis (2006), cities of the future will not be made of glass and steel as ‘future’ urbanists have proclaimed but rather constructed out of crude brick, straw, recycled plastic, cement blocks, and scrap wood. Some estimates show that by 2030, two billion people will live in informal settlements (McGuirk, 2015). Thus, how we deal with and fold informal settlements into the urban fabric of our growing cities will be key variables determining the way these cities function and prosper in the future.

It is important to understand informal settlements not only as a noun or as a technical expression, but a place where people live and develop social connections, therefore these settlements need and deserve greater attention from policymakers. They should be considered as formal as the asfaltização or asfalto (the asphalt city). While informal settlements might be lacking land tenure, they remain to be strong communities and with their own form of self-governance, yet without the infrastructure and legal components that bind the asphalt city, such as clean water, sewage, sanitation and hygiene services. McGuirk (2015, p. 25) succinctly defines informal settlements:

“(…) as informal not because they have no form, but because they exist outside the legal and economic protocols that shape the formal city. But slums are far from chaotic. They may lack essential services, yet they operate under their self-regulating systems, housing millions of people in tight-knit communities and proving a crucial device for assessing the opportunities that cities offer.”

In a similar definition, according to the United Nations (UN, 1997): “informal settlements are: 1. areas where groups of housing units have been constructed on land that the occupants have no legal claim to, or occupy illegally; 2. unplanned settlements and areas where housing is not in compliance with current planning and building regulations (unauthorized housing)”. In short, precarious settlements have vulnerabilities caused mainly by the lack of basic infrastructure, urban planning and land tenure.

Nonetheless, favelas, as a form of informal settlements, should not be considered, as they often are, especially in the media, to be places for thugs and drug dealers and generally neglected by the society and policymakers. Rather, they should be seen as having cultural and social presence and importance. “From the sociocultural point of view, favelas have a perspective on sociability different from the rest of the city, with a plurality of coexistence of social subjects in their cultural, symbolic, and human differences and a great use of common spaces due to the high density of buildings” (Souza e Silva, 2009, p.96). Thus, rather than informal, McGuirk (2015) would see them as communities in the classic sense but only lacking formal recognition.

In the same vein as McGuirk, Fernandes (2011) expressed that a key aspect of favela informality is the lack of formal housing claims. Yet many residents feel secure with the tradition of handed down de facto property rights that are at the heart of customary practices in informal settlements. Understanding the role that land tenure, or legally declared land ownership, plays in the definition and structure of informal settlements becomes an important aspect of knowing how informal settlements are folded into the urban fabric.

In 2009, the social organization ‘Observatório de Favelas’ based in Maré, Rio de Janeiro, proposed the following theme: “What is favela, after all?”. According to its Declaration of Principles, a favela was considered: “A territory where the incompleteness of state policies and actions are historically recurrent, in terms of the allocation of urban infrastructure services and collective equipment resulting in the lack of guarantees and realisation of social rights” (Souza e Silva, 2009, p.96). Therefore, “from the socio-urbanistic point of view, [favelas are] informal in relation to the standards set by the State as it is characterised by self-construction, high density, and extreme degree of environmental vulnerability” (Souza e Silva, 2009, p.96). The deployment of the Favela-Bairro Programme intended to bring about higher standards not only to the public spaces, but also the urban infrastructure. It represented a shift from the historical policy of removal and in turn began a new era of urbanising the favelas. Yet, in general, favelas continue to be seen conceptually in an extremely simplistic way. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), for instance, refers to the favela as a ‘subnormal cluster’ with the following characteristics: “A group consisting of at least 51 housing units (shacks, houses, etc.) lacking most essential public services, occupying or having occupied until a recent period land owned by others (public or private) and generally arranged in a disorderly and dense manner” (Freely translated by the authors from IBGE, 2010, p.19).

The above definitions have been at the heart of many favela studies. They have often been identified in coherence with the word ‘chaos’. Buildings within the informal clusters, in general, do not follow any intentional or formal tendencies, but are the result of the essential need for shelter. These characteristics as well as their similar appearances can lead one to imagine that there is a kind of ‘architecture without architects’ common feature to all informal urban settlements. They have become a global phenomenon, with slight differences related to regional conditions. Indeed, each city has its own features developed by its cultural and biophysical influences, but precarious conditions concerned with physical-spatial attribute seem to shape the image of the place (Davis, 2006). Owing to these conditions and structural designs, they are often seen as a marginal and unworthy form of urban development, which, in turn, has contributed to the social stigmatisation and spatial segregation of millions of people. This kind of behaviour is widespread in society, even at the institutional level. This is the reason why the removal initiatives employed for so many decades in the favelas, rather than upgrading, were so prevalent.

It is important to remember that besides morphological issues, meaning “the typical self-construction, high density, and extreme degree of environmental vulnerability”, as mentioned before, there are aspects inherent in the favelas, particularly regarding community and self-empowerment, that need to be understood. The Favela-Bairro programme was limited to what it could achieve and thus did not cover everything. It is an initiative for the urbanisation of slums. However, it is fundamental to point out that, in addition to the urgencies related to the fundamental issues of improving living conditions in poor communities, there is an equally important aspect: the culture in the favelas and specifically in each favela. In Rio de Janeiro, for example, the favelas are absolutely interconnected with the so-called formal parts of the city, in flat areas, hills, beaches, etc. They are widespread throughout the city. Furthermore, in each place, there are formal and spatial characteristics where different forms of occupation, density and height are found. This is the reason why it is so complex to define a particular urban morphology that characterises the favelas of this city. Paola Berenstein Jacques (2001), for example, studies the issue of informal clusters through the lens of their cultural dimension using an aesthetic approach. She seeks to develop conceptual figures by dissecting what she calls the aesthetics of the favelas, “the aesthetics of these contrasting spaces or 'other spaces' - 'heterotopias' (...) - built and inhabited by ‘others’ (non-architect)” (Jacques, 2001). She refers to the role of residents in building cultural and social presence. This conceptualisation sets forth the perception that the otherness of these spaces, called informal, primitive, or wild, was, until very recently, despised by architects and urban planners. Yet, favelas retain a particular wealth of spatial identity, and, to intervene in this universe, technicians must understand this difference.

Favelas in Rio: a historical perspective

As it can be seen throughout this work, there are several reasons for the growth of the population in favelas in Rio de Janeiro. However, it is important to highlight the migration of populations from other states, the endemic social inequality in a growing population and the lack of concrete initiatives and continuity of public policies for the urbanisation of slums. Rio’s favelas are known worldwide in an emblematic fashion through films, dances, and popular culture. In the eyes of the world, they are the epitome of Rio and Brazil itself, because of the beauty of its natural attributes and their cultural and artistic recognition, and urban violence. Before moving on, as a way of illustrating the evolution of favelas in Rio de Janeiro, between 1960 and 2010, while the population of Rio de Janeiro grew from 3,307,163 to 6,320,446, which represents a 91% growth, the population living in favelas jumped from 335,063 to 1,393,314, amounting to a 315% growth. The history of the favelas is a microcosm of the history of Rio and of the image of Brazil (Table 1).

Table 1 Population living in favelas in Rio de Janeiro

| Year | Population living in favelas | (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 169,305 | 7.2 |

| 1960 | 335,063 | 10.1 |

| 1970 | 563,970 | 13.2 |

| 1980 | 628,170 | 12.3 |

| 1990 | 882,483 | 16.1 |

| 2000 | 1,092,958 | 18.8 |

| 2010 | 1,393,314 | 22.1 |

*Proportion of people living in favelas among the city of Rio’s population.

Source: Cardoso (2007, pp.52-53); Perlman (2003, p.4)

The Early Years: 1890-1930. Origins and tabula-rasa

The officially accepted origin history of Rio de Janeiro's favelas points to soldiers who had allegedly returned from the Paraguayan War (1870) and the War of Canudos (1897). Other sources suggest that these communities were formed by freed slaves landing in the port region of the city (Catalytic Communities, n.d.; Wallenfeldt, 2019).

Starting in the beginning of the 20th century, Pereira Passos, an engineer, and former mayor of Rio de Janeiro (1902-1906), instituted a plan to reform the city centre of Rio de Janeiro in line with the revitalisation of Paris, France (Outtes, 2005). This led to the demolition of hundreds of residences that “represented the past”, including tenements and working-class houses that were in direct opposition to Passos’ triad of beautification, healthiness, and street clearing. In 1930, Donat-Alfred Agache, a French architect, was invited to design a plan for Rio de Janeiro (Outtes, 2005). He suggested that greater attention should be paid to social order and public safety, in addition to hygiene and housing remodelling. Thus, Agache recommended moving the favelas to the outskirts of the city. It is thus clear that stigmatisation and segregation has been the main strategy for dealing with precarious settlements, and that there was little effort made to upgrade the urban conditions.

The mid-20th Century: 1931-1960 - changing minds, shaping responses for social housing

Around the middle of the 20th century tabula rasa practices were replaced by ideas that were centred around the attenuation of the difficulties faced by the favelas. A general feeling that the favelas were ingrained into society and that pure eradication or relocation which was not necessary began to prevail. From the 1930s to the 1950s, there was a special interest in mitigating the problems associated with the growing number of slums through the Housing of Social Interest (HSI). HSI linked ‘popular’ housing provision to pension funds via the Institute of Retirement and Pensions (Buonfiglio, 2018). Some notable social housing projects were launched by renowned Brazilian architects, such as Afonso Eduardo Reidy, Flávio Marinho Rego, Firmino Saldanha, Francisco Bolonha, among others.

Between 1941 and 1943, much of the housing projects focused on the construction of working-class clusters (Parques Proletários), such as Caju, Gávea, Leblon, Penha, etc. The buildings were not intended to be a definite housing solution; rather, they were designed to temporarily house displaced populations of the slums, e.g., they were built of wood (instead of masonry and concrete, which would have implied permanence) and lacking architectural integrity.

Between 1947 and 1962, the Leão XIII Foundation operated in 33 favelas in Rio (Robaina, 2013). The non-profit organisation brought benefits, such as basic services, the construction of houses, and the maintenance of social centres in large favelas. This Catholic entity played an important role in giving social protection to the favela’s dwellers as the Church filled the void of those basic services for which the asfalto government did not provide. Nevertheless, the range of the coverage was limited to only 33 favelas, in about 15 years of work. It should be stressed that, during these years, according to the 1950 census, there were 169,305 people (Perlman, 2003, p.4) concentrated in just over 100 slums (Cardoso, 2007, p. 52).

Middle of the last half of 20th Century: 1960-1980s. Removal vs upgrading favelas and living conditions during dictatorship

During the middle of the 20th century the emphasis swayed back to the removal of the favelas and away from figuring out ways to improve the living conditions of the favela residents. In Rio, by the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s, this removal strategy took place in many favelas, among which stands out one of the biggest in the city: Favela da Maré, (Santos, 2016; Silva, 2006). During the administrations of Carlos Lacerda (1960-1965), Negrão de Lima (1965-1970) and Chagas Freitas (1970-1975), all former governors of the bygone State of Guanabara, the policies of favela removal intensified. More than 130,000 people were removed from 80 favelas during this period (Valladares, 2005). It is worth remembering that in the “Census of 1960, the population in slums already [accounted for] 335,063 people, corresponding to 10.15% of the population of the city. While the total population grew at a rate of 3.3% per year during the decade, the slum population grew to 7.06%, more than double” (Cardoso, 2007, p. 53).

In 1968, the Coordination of HSI of the Metropolitan Area of Greater Rio (CHISAM), an agency linked to the National Housing Bank (BNH), was created, which aimed to eliminate the informal part of favelas by transforming its residents into homeowners (Denaldi, 2003). The programme was nullified in 1974 when the removal of favelas in Rio was considered out of question. This strategy tended to create more problems than solutions, as it disrupted the family atmosphere of the favela population.

In the early 1970s, the number of favela dwellers was estimated at 563,970 people, which corresponded to 13.2% of the city’s population. In 1975, BNH created the Urbanised Lot Financing Programme (PROFILURB), with the aim to create “urbanised lots and housing embryos, [including infrastructure finance and land ownership legalisation], for the population with an income of 0 to 3 minimum wages”. However, after 15 years, less than 43,000 lots had been financed throughout Brazil (Denaldi, 2003). In reality, the programme was not designed for favelas, but as an alternative for poor people who would be able to leave the favelas and live-in urbanised places.

In 1979, the Self-Construction Financing Programme (PROMORAR) was created by the Rio de Janeiro government. The programme sought to maintain the population in their own place (the favela), with improvements in buildings and urban infrastructure. Yet, in 1980, 628,170 people were living in the favelas, corresponding to 12.3% of the inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro (Perlman, 2003). In 1983, the state government launched the Every Family, One Lot programme for widespread land regularisation, but without effective results. The original purpose was to achieve the regularisation of one million lots all over the state of Rio de Janeiro. In 1985, only 32.817 lots were officialised, among which 31.084 in the city of Rio de Janeiro. In 1986, 16.686 more were regularised (Cardoso e Araújo, 2007). Due to a serious economic crisis in Brazil in the 1980s, the BNH was extinguished in 1986, having failed to fulfil one of its most important tasks, i.e., adequate housing to the poorest sections of the population.

With the re-democratisation of the country in 1985, following the 21 years (1964-1985) of national dictatorship, municipalities took on more active roles with the assumption that more participatory and democratic initiatives were needed. It was impossible to claim rights beforehand, even some of the most important and basic ones, such as the right to housing. The simple right to claim a home was considered a subversive act. The programmes that emerged then, such as Every Family, One Lot, assessed the qualitative levels of intervention to be assumed by the public administration barring mass removals and only allowing removals in areas at risk.

By 1990, there was already a population of 882,483 people in favelas, which corresponded to 16.1% of the city's residents (Perlman, 2003, p. 5). In 1992, the Rio de Janeiro City Master Plan indicated the need to integrate favelas into neighbourhoods, and more importantly, it acknowledged the necessity of “preserving the typicality of local occupation and the provision for the implementation of progressive and gradual infrastructure” (Art. 152).

During the Municipal Governments of Mayors César Maia (1993-1996) and Luiz Paulo Conde (1997-2000), there was an overt convergence of initiatives that intended to deal with urban problems in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Large urban projects took hold throughout the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the search for solutions to recent and historical problems.

In 1993, Rio de Janeiro's City Hall created the Executive Group for Studies of Popular Settlements and, subsequently, the Extraordinary Secretariat of Housing, which preceded the Secretaria Municipal de Habitação (SMH - Municipal Housing Secretary), in 1994, which would also take over the Mutirão Project. Seven housing programmes were organised - Regularização de Loteamentos, Regularização Fundiária e Titulação, Novas Alternativas, Vilas e Cortiços, Morar sem Risco, Morar Carioca, Bairrinho, and Favela-Bairro6.

The Favela-Bairro programme, beginning in 1995

The Favela-Bairro programme sought to align the existing infrastructure of the favelas with that of the asfalto for the provision of physical-spatial improvements and infrastructure, as a way to increase the quality of life of citizens by bringing: basic sanitation infrastructure, geological containments, accessibility to services and adequate housing and granting of land tenure, among other public initiatives. At that time, it was considered a progressive housing policy that involved close collaboration between the SMH and the Instituto Municipal de Urbanismo Pereira Passos (IPP - Pereira Passos Institute). These organizations coordinated thousands of professionals from Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), educational institutions, social entities, management companies, concessionaires, construction companies, among others, for everything from programmes conception to social monitoring and urban orientation (IPLANRIO/PCRJ, 1994; Fiori et al., 2000; Conde et al., 2004).

Community participation was also fundamental to the initiative. Whether initiated by individuals or through collective claims brought forward by Residents’ Associations, there was constructive dialogue to foster positive changes. Initial ideas and targets were built within each community, before the beginning of the development of the architecture and urbanism design. The ‘public hearing’ participatory instrument made it possible for teams responsible for the development to present the architectural and urban proposals to hundreds of residents with varying participation across the favelas. Many suggestions were well received, serving as beacons for community desires concerning the technical reports (IPLANRIO/PCRJ, 1994; Fiori et al., 2000; Conde et al., 2004)

At the outset of the programme, the Institute of Architects of Brazil - Rio de Janeiro (IAB-RJ) organised a competition for the “Selection of Methodological and Physical-Spatial Proposals Related to the Urbanisation of Favelas in the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro”. Private architecture firms were invited to participate in redesigning and urbanising the favelas with fifteen firms and organisations being selected to develop the architecture and urbanism projects for a corresponding number of informal settlements (IPLANRIO/PCRJ, 1994; Fiori et al., 2000; Conde et al., 2004).

The programme promoted urban upgrading by offering social and environmental infrastructure in the favelas with 500 - 2,500 households. The aim was to integrate these neighbourhoods using the planning instruments and processes outlined in Rio de Janeiro's Master and Strategic Plan. A US $180 million loan from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), combined with US $120 million from municipal resources, provided monetary bases for the initiative to take the initial and fundamental steps.

Much of the work of planning, discussing with the community, developing projects, choosing the communities priorities, etc., aims to strengthen centralities, value public space, implement sanitation infrastructure, and oversee the transition from irregular housing into planned housing. In addition, there was a growing attention to accessibility, housing equipment, education, leisure facilities, health, and other fundamental issues regarding the environment, community, culture, economy, career, sociability, welfare (IPLANRIO/PCRJ, 1994; Fiori et al., 2000; Conde et al., 2004). One of the programme's social initiatives was to preclude the removal of residents, which was, as already mentioned, a common practice in housing policies until the 1970s. In cases of geological danger, environmental vulnerability, or impediment to public works, etc., demolitions were undertaken judiciously and, on a case, -by-case basis, echoing Jamie Lerner’s ideas of “urban acupuncture” rather than a bulldozer mentality.

In 2000, the Municipal Secretary of Housing, Sergio Magalhães, who was responsible for the design and development of the Favela-Bairro programme, left office. At this time, the number of inhabitants in the favelas was 1,092,958 people, or 18.6% of the city's population (Perlman, 2003, p. 5) (Table 1). Born from the Favela-Bairro´s experience, several proposals, such as the Morar Carioca, Minha Casa Minha Vida and Casa Verde e Amarela programmes7, were endeavoured and put forth to raise the environmental and sanitary quality of the favelas.

Projects Bairrinho, Favela-Bairro, and Grandes Favelas

In the 1990s, the Favela-Bairro programme was one of the leading programmes and policy initiatives for upgrading medium-sized favelas (500 to 2,500 people). At the same time, two other programmes were working in tandem - Bairrinho, which dealt with favelas with populations between 100 and 500 inhabitants, and Grandes Favelas, which comprised favelas with more than 2,500 residents (Table 2). In addition to the differences in scale, the locations of the favelas required different strategies for dealing with social, economic, and operational constraints. These strategies included housing models, accessibility, mobility, social services (day-care centres, schools, health clinics, etc.), passageways and roads (giving accessibility through the high concentration of small buildings), infrastructure, and public spaces, etc. (IPLANRIO/PCRJ, 1994; Fiori et al., 2000; Conde et al., 2004).

Table 2 Population in each programme

| The Three Programmes | |

|---|---|

| Programme | Population |

| Bairrinho | 100 - 500 residents |

| Favela-Bairro | 500 - 2,500 residents |

| Grandes Favelas | More than 2,500 residents |

Source: Cardoso (2007, p.74)

The perceived strength of these programmes stems from the open communication routes. Each intention and action were designed to be fully discussed with the community, individually and collectively, before any action was taken. The main objective of the Favela-Bairro programme was to enhance the quality of the urban space by transforming the favela in terms of infrastructure and vitality, which included, but was not limited to, issues of health and social justice.

Bairrinho - Favelas Vila Canoas and Pedra Bonita

The Bairrinho programme, a pilot programme within Favela-Bairro, under the administration of Mayor Luiz Paulo Conde (1997-2000), was dedicated to small favelas and implemented in Vila Canoas and Pedra Bonita favelas. Vila Canoas, our main case study (figure 2) is a small favela that was formed in the first half of the 20th century by employees of the Gávea Golf Club, a club frequented by the city’s elite, in the neighbourhood of São Conrado. In the 1970s, its residents benefited from the Every Family, One Lot programme and formed a community. The purpose of the Every Family, One Lot programme was to legalise land ownership, in turn giving dignity to the favela residents. It is important to highlight that without a formal residential address, it is almost impossible to have a job in Brazil. Besides that, having a legal address gives one legitimacy to demand public services, e.g., electricity, sewage, water, among others. The Pedra Bonita favela also consists of former employees of the Gávea Golf Club. The communities sit at the foot of Pedra da Gávea in the Tijuca Forest, skirting the Canoas river and a dense forest. The residential units are irregularly built on steep topography. Due to these characteristics and the dense concentration of buildings, there is little vehicle access. As a result, most of the residents can only access their homes on foot. Together, in 1997, the favelas housed 356 households, increasing in 2008 to 588 households (Salomon, 2008).

The Bairrinho project was developed between 1997 and 1998 by the ArquiTraço firm to diminish stressors on the communities. The primary objectives were to improve sanitation infrastructure, containments, accessibility, public squares, land regularisation, and other community projects. These included a day-care centre for 100 children in Pedra Bonita, a Municipal Centre for Social Care (CEMASI), a Family Health Centre, and an Urban and Social Guidance Post (POUSO). The participation of the Association of Residents and Friends of Vila Canoas (AMAVICA) was fundamental for the programme's success, as viewed by its inhabitants, and for the government deciding on its continuation during the administration of Mayor César Maia (2001-2004/2005-2008).

According to Isaias Machado, the former President of the AMAVICA, it was a long uphill struggle to keep the government interested, “as City Hall broke their promise to 179 families by not continuing the work”. Political conflicts with altered managerial and governmental positions, after the election for the Mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro (2000), led to new interests and priorities. To get City Hall to recognise the community again and stick to what they had promised, AMAVICA shamed them into taking action after public protests broadcast on television. “We organised and worked with the TV stations which interviewed members of the community explaining how the city forgot about them and we also went to City Hall to show that we were not forgotten.” Mr. Machado reported: “By using the local broadcast media, we were able to get City Hall to resume the construction and continue what they had started in Vila Canoas."

Favela-Bairro Programme - Pavão-Pavãozinho Favela

Two favelas make up the Pavão-Pavãozinho-Cantagalo neighbourhood (figure 3), which is located on a steep hill between the neighbourhoods of Copacabana and Ipanema. Pavão-Pavãozinho has about 5,500 inhabitants distributed in approximately 1,800 households. Cantagalo, on the other hand, consists of about 4,700 residents living in approximately 1,400 houses, resulting in a population density of 800 inhabitants per hectare (IBGE, 2010). Notwithstanding, according to some NGOs, the 2010 census seriously underestimated the population, suggesting that the actual number might come closer to 20,000 inhabitants in the region.

Two instances characterise the growth of the area. First, in the early 1900s, Cantagalo was settled by former slaves from the interior, primarily from the states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo8. Second, in the 1930s, Pavão-Pavãozinho was formed by migrants from Northeastern Brazil. Cantagalo was created to house those working for the affluent residents of Ipanema and Copacabana. This is still the main occupation of residents today (see figure 4). The community’s growth in the early 20th century was a direct result of the needs and wants of wealthy classes along the beaches, who desired cheap labour for daily maid service.

As a result, the favela is seen as an important part of the city outside the established urban structure. A guide who took one of the authors for a visit in Cantagalo stated that “Cantagalo is now a prime real estate area, but the residents will never be driven out it because who will clean the houses in Ipanema?”. By understanding this, it is easy to explain why Cantagalo was a prime candidate for the Favela-Bairro programme.

Despite these efforts, Cantagalo and Pavão-Pavãozinho have survived numerous removal attempts. This was especially true between 1960-1970, during the Government of Carlos Lacerda (1960-1965) and the first half of the military dictatorship occupation of the Federal Government (1964-1985). The favelas of Pinto and Catacumba, for example, which were located less than 1 km away from one another, were victimised by alleged “accidental” fires and then wiped out during this time period.

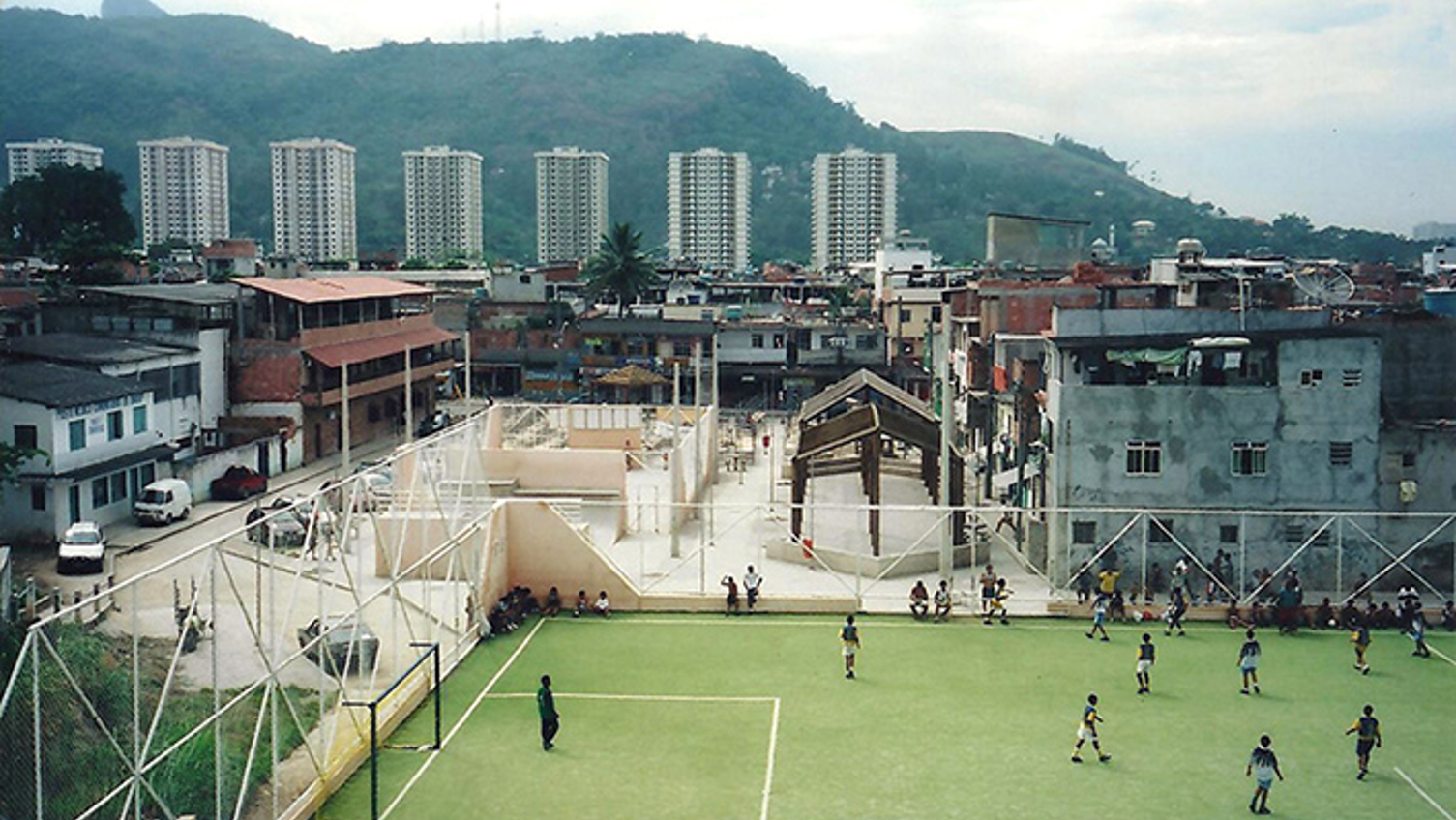

Grandes Favelas Programme - Favela Rio das Pedras

The Rio das Pedras complex (figure 5) is in a region of strong economic growth since the 1970s. Its population is approximately 54,700 people spread out through 18,700 households (IBGE, 2010), covering an area of about 60 hectares. The area was first occupied by migrants from the northeast of the country in the 1950s. Although the region was difficult to reach due to the lagoons and mountains that surround it, the urbanisation of the affluent area of Barra da Tijuca boosted the density of the favela. Like many of the favelas in Rio, the community has been historically plagued by gangs and drug trafficking, resulting in the political dominance of militiamen to purportedly combat gangs and drug activity9.

From a geographical perspective, the area is swampy and flooding is a recurrent and persistent problem. This has resulted in great instability of the buildings and structures with intense mudslides and flooding. During the first term of office (1983-1986) of Leonel de Moura Brizola, the socialist-minded governor, the landfill was transformed into a housing site for families displaced by floods in 1984, within the programme Each family, One lot of CEHAB-RJ (Mendes, 2006, p. 155), which resulted in the construction of 130 residences through the land tenure system.

Parallel to all of Rio de Janeiro’s large favelas, Rio das Pedras structures were built in several phases. They came together and overlapped in different layers, from initiatives that were undertaken by the government, sometimes by the population itself. This resulted in different typologies and forms of structures. For example, the regions of Vila dos Pinheiros and an area also called Rio das Pedras are central areas with greater prestige.

As designed in the Project Intervention Plan, roads were opened, infrastructure was strengthened and built, day-care centres and leisure facilities, including improvements in the headquarters of the Residents Association, were constructed. There was an attempt at land regularisation, but it was never successful. Unfortunately, as in other favelas, there was no continuity in government actions. Thus, at extremely spaced intervals, improvements were made in sanitation infrastructure, residential, education, and health equipment, without one unified systemic vision. As a matter of fact, very few favelas have benefited from the Grandes Favelas programme.

Participation and interest of the residents

The Bairrinho, Favela-Bairro, and Grandes Favelas programmes sought to provide the residents of the favelas with a minimum of conditions, equipment, and infrastructure seen in the so-called formal neighbourhoods. Although not always valued by technicians, academics and civil society, there was an Urban and Social Guidance Post (POUSO) in each community. Its objective was to function as a “centre of urban and social counselling, with teams from several Municipal Secretariats” (Fiori et al., 2000, p.54). These posts were created for the resident population to have access to services, rights, and adequate public spaces, among other facilities. It intended to coordinate a transition towards a new housing experience. In addition to POUSO, Residents’ Associations were important to the ongoing success of the programme, especially after initial work was completed.

“[The Residents’ Associations were] responsible for maintaining infrastructure and services such as garbage removal, maintenance of drains and sewers, and distribution of mail and utility accounts. Increasingly, these tasks [had been] transferred by relevant utility companies to the community level since the mid-1990s. Therefore, COMLURB10, CEDAE11 and Light12 [hired] the Residents’ Associations to perform at least part of their service and the Associations, in turn, [hired] community labour to perform the specific tasks” (Fiori, 2000:, p. 54).

The participation and interest of the residents of each favela were important to bring about the desired transformations. Their involvement helped guide the work of managers, designers, and builders. By way of illustration, the managers and architects consulted with residents for the projects to be approved by informal public hearings. In addition, the SMH trained Housing Policy Agents to channel information and requests to tackle problems related to the work. People from the community were also recruited to work for the construction companies responsible for the urbanisation of their favela. Often, the success of the community project depended on the involvement of populations and their suggestions, criticisms, complaints, and demands, by pointing out problems and potentials.

The experience, as shown through different institutional programmes, of improving conditions in favelas has resulted in some lessons learned. The Favela-Bairro programme, while being a great exercise for technicians and academics, lacked the essential and continuous participation of the local community, after the enthusiasm and motivation of the initial moments of the implementation of the programme. The programme dealt with different scales, in many parts of the city, with concrete urban benefits that gave better quality of life to populations living in favelas. The innovative character of the proposal, with strong involvement of the municipal government, was based on offering urban solutions to favelas similar to those existing in the so-called formal parts of the city. The programme sought to integrate the favelas with the city, avoiding their stigmatisation. The weakness of this initiative was mainly due to political rivalries.

The views of the programmes’ architects

As mentioned previously, key architects (Manoel Ribeiro, Jorge Mario Jáuregui, and Daniela E. A. Javoski) involved in the three redevelopment programmes were interviewed. The objective of these interviews was to know what it was like on the ground. The architects were asked to discuss four main areas of inquiry - how they felt about their programme, negative and positive aspects, possible impacts on the city of Rio de Janeiro, and further thoughts.

The first question posed to the group was how they would describe the three programmes (Bairrinho or Favela-Bairro or Grandes Favelas) and with which they were most involved. All the architects saw the Favela-Bairro programme and the contest around it as an opportunity to think outside the box when it came to favelas. In their minds, it was the first time the city of Rio had thought about the favelas as being part of the greater city or the asfalto. As one of the architects stated, it “was the first favela urbanisation programme with a great impact, since favela urbanisation was a practice, little implemented at that time. It was the first comprehensive approach to all the topics involved in the urbanisation of favelas” (Ribeiro, 2020).

As well as considering these programmes as the first attempt at favela upgrading, the architects saw them as a way to spawn new ways of thinking involving new participants. The contest that the architects were involved in “made room for teams from established architect firms and recent graduates too”. It also encouraged “enough flexibility to allow methodological experiments, with errors and answers” (Javoski, 2020).

The second question asked was how they saw the programme(s) in terms of the infrastructure and environment of the favelas and what were the positive and negative aspects of the programme. Regarding this question, there was a general sense that the projects had a noble purpose, but it lost momentum to complete what it had started. There was also too much emphasis placed on the public realm vis-à-vis the private. Jáuregui (2020) stated during the interview: "It was a programme that only acted in public areas. Private buildings were not contemplated. It was assumed that actions in public spaces would motivate improvements in private spaces”. As expected, the priority was to use public resource in public areas. This deficiency of overtly connecting the private realm was a common theme expressed by the interviewees.

What stood out for them as to why the programme was not as successful as it could have been is twofold. The first being the discontinuity in the programme, the stop-and-go nature of it. The second was the time frame set for accomplishing the job, which gave little time for a deep understanding of each community. These points of view, common to the interviewees, seem fundamental to take in the reasons for the weaknesses of the Favela-Bairro, in a practical sense.

Thirdly, we were concerned, from an institutional action perspective, with the impact the programme might have had on the city of Rio de Janeiro and, more specifically, on the favelas, and whether the programme was given the necessary attention it needed to have its objectives accomplished, i.e., mainly the improvement in the living standards of the inhabitants of the favelas. The overall perception was that the programme was important to the city because at the very least it had the community speak for themselves of favelas in constructive terms. The programme has brought to the informal settlements the basic sense of the “right to the city” (Lefebvre, 2009), where they could see themselves as members of the city, with all the rights to land ownership and adequate living conditions that are provided henceforth.

But, echoing what was previously stated, there seems to have been an overarching theme, that is, the city failed in its execution of the programme. “I think the City of Rio has erred in the process of maintaining the interventions. The favelas, which before the Favela-Bairro programme were not part of the maps of the city of Rio, after the interventions continued outside the institutional routine of maintaining the city's public spaces” (Ribeiro, 2000). There are many reasons, beyond purely financial, to explain the lack of interest in one area as opposed to another. Ximenes and Jaenisch (2019, p.7) present a good explanation for this: “In many cases these sites consist of areas of recent expansion (...) or due to the negligence of the public power, which often refuses to intervene in places that present situations of environmental risk or require a greater complexity in the intervention.”

Lastly, the interviewees were asked about their impressions/opinions about the recent policies towards improving living standards in the favelas in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the state of Rio de Janeiro, and/or Brazil. There was a general feeling that the Favela-Bairro programme did increase urbanisation which motivated investment in the favelas. However, with the weakening of the Favela-Bairro concept, some voices argue that investment has also been driven by land speculation. Some believe the programme was envisaged as a way to help developers get a hold of spaces that could be controlled and sold. This was especially true leading up to the World Cup (2014) and the Olympics (2016) in places next to favelas. Thus, what was considered as a leading government initiative has now, after the abandonment of the government upgrading programmes, become a private sector land tenure programme. This does not necessarily mean that government sectors have vested interests when proposing the upgrading of favelas, unless it corresponds with a major sporting event such as the Olympics or the World Cup13.

Notwithstanding the fact that the programme was good in the sense that it empowered and urbanised the favelas with much-needed infrastructure, there seems to be a prevailing view that questions for whom that upgrading was. Was it for the residents of the favelas or land speculators? It is important to stress that before the Favela-Bairro programme, Rio de Janeiro had never implemented a judicious and efficient urban intervention in favelas. Hence, the programme was responsible for and did succeed in upgrading the favelas. Thus, in turn, it brought a renewed value to the place where it was implanted and, of course, the importance of the confidence that comes with land tenure, which benefits the entire neighbourhood.

As it could be understood, favelas are informal and unplanned places: “The occupation of the favelas was disordered because of the absence of tenure security. As a result, the form of occupation and style in which houses were built is completely incompatible with other traditional forms of urban occupation that are determined by urban legislation and civil law.” (Castro, 2002, p.159). Being so, it is unusual to have a registry of an urban property in favelas. This does not mean that properties such as land or houses are not sold or bought. It only means that a title deed cannot be officially registered: “Nothing is registered at the deeds registry, unless it is precise, official and legally defined in the legislation. The title deed is only issued according to precise formal definitions. The claimants must have their personal situations identified properly, a condition which is seldom found in the favelas.” (Castro, 2002, p.160). Asset appreciation was good for ‘real estate speculators’. It is necessary, however, to recognise that this was not the result of a formal business officially endorsed by the government. Therefore, it would be absolutely nonsense to preclude from offering urban improvements to typically precarious settlements, such as favelas, so that there would be no land appreciation. In conclusion, it must be stressed that the Favela-Bairro was, in general, an upgrading programme that, above all, improved the conditions of the populations residing in the favelas involved.

Discussion

Providing the favelas with sanitation infrastructure, geological containments, accessibility resources, education and health equipment, leisure facilities, etc. were important and desirable initiatives made possible by the Favela-Bairro programme and its variants. However, following historical common practices, the lack of public policies associated with the improvement in social conditions seems to have been a critical problem that undermined the good intentions of the programme in the medium term. Without knowing the social and historical context, one may think that the governmental programmes, such as Each family One Lot, for example, would entail the government production of “new favelas”. In reality, the State creates precarious settlements when it is remiss in its duties of urban planning and management. The delay in adopting a broader and deeper systemic position by public administration officials has led to a bleak view of the programme. Moreover, the lack of interest in the communities, the discontinuity in public management, and the resurgence of parallel powers (drug trafficking and militias) contribute to this situation. A point to be considered is that, except for specific situations, the practice of removing favelas has not been recently adopted. At present, it is necessary to recognise the voice of the poorest population. The removal of large population contingents away from urban centres to the periphery, forcing them to break relationships with family and friends, has not been a recurrent practice.

Due to its relative success, the Favela-Bairro programme has continued to be ‘recycled’ in other versions. However, these public initiatives did not have the scope or clarity of the original programme. The Morar Carioca, Minha Casa Minha Vida and Casa Verde e Amarela programmes do not have the completeness and specificity necessary for the upgrading of favelas (see footnote 9). The architects Luiz Paulo Conde and Sérgio Magalhães developed a participatory work process with the populations living in the favelas. They had been able to assemble highly trained technical staff from the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, with clear objectives. The public process of personnel selection brought the practical experience of professionals linked to the private economy. It was a progressive way of dealing with poverty and poor living standards in the favelas.

The lack of investment in infrastructure in Brazil is evident in the precariousness of housing, sanitation, mobility, education, security, etc. The favelas, despite their cultural richness, symbolise the negligence to which an important segment of the population is subjected. It also potentially represents the consequences of the country’s socioeconomic inequity and the nefarious actions of rulers in different spheres - Federal, State, and Municipal.

The discontinuity in government initiatives is another aspect of the problem. Political rivalries and the lack of a global vision squandered previous gains. The Favela-Bairro programme is an example in which there was no adequate maintenance over time. The victims of this negligence are the residents of each of the favelas, which return, essentially, to the previous stage of precariousness and environmental and sanitary vulnerability. Due to the absence of effective government action, the population is the great producer of its own space and the problem solver in everyday life, which is evident after having survived recurrent dispossession. Visits in 2019 by the authors to the favela Santa Marta (figure 6), in Botafogo, and favela Vila Mangueiral, in Campo Grande, bear the testimony of the lack of care for public goods and the scarcity of attention to the poor sections of the population.

Conclusion

Society certainly holds favelas in contempt because of the trivialisation of issues routinely present in the lives of its residents, such as violence and precariousness. However, there still is a universe in which personal, political, and social spaces and identities must be valued. In addition, Brazil’s social inequality is one of main contributing factors undermining initiatives to reverse precarious living conditions, including housing. Political, social and economic priorities do not seem to meet the needs of the poor. Regardless, an appropriate urban project can change an existing situation, contribute to the local economy and even provide the cultural life of these places in which approximately 22% of Rio’s population live. Yet the lack of infrastructure and sanitation, as well as police brutality, militia control, drug trafficking, among other factors, tend to oppress and destabilise the communities.

Our analysis provided interesting personal and technical dimensions from professionals who participated in a favela upgrading programme. The designers offered important insights into the opportunities put forward by the project process. This included being able to add something significant that was not there before and, in turn, enrich people’s quality of life. But, as seen earlier, this was only possible for the Favela-Bairro programme which considered strong public participation as necessary, with the public manifestation of the people who lived in the favelas. They also advance potentialities for further improving these types of programmes.

The main takeaway from our study is that despite the participatory nature of the programmes, the benefits seem to have been lost over time as many of the favelas return to their previous state of disarray. The lack of maintenance of the facilities built throughout the programme development in many favelas seems clear to the naked eye (

and ). Historically, the endemic paucity of long-term commitment and the constant political disagreements between different administrations, which is typical of the Brazilian State, hinder the strength of the protracted fight for better living conditions for the inhabitants of Rio's favelas.The Favela-Bairro programme and its offshoots attempted to deal with and eradicate several issues that plague the favelas of Rio. While the programme succeeded in some important aspects, it failed in others. Ergo, there is much we can learn from it. The lessons learned from this study can be used as a starting point for other cities throughout Brazil, Latin America and other developing countries dealing with informal settlements. Coming to grips with the growth of informal settlements is not a short-term issue, but rather a foundational issue for much of global urbanisation underway in the 2st century.