Introduction

Access to affordable housing is becoming increasingly challenging in the global context. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis has further compounded the previous three decades of policy shift towards deregulation of social housing, which has significantly reduced the efficacy of both social and economic instruments designed to address housing needs (Austin, 2003; Tummers, 2016; Desmond, & Gershenson, 2016; Aglietta & Timbeau, 2017; Pittini, 2018; UNECE, 2014). Switzerland illustrates the policy shift encouraging home ownership and the commodification of rent-setting arrangements (Kemp, 2000, in Lawson, 2009, p. 61). Since the 2008 crisis, housing cooperatives have multiplied in Europe (Pittini, 2018). Many self-managed housing experiences have been built bottom up by civil society groups in a voluntary and decentralized manner (Wendt, 2018; Foster & Iaone, 2019; Vey, 2016; Vidal, 2024; Koch, 2021; Khatibi, 2022; Balmer & Bernet, 2015; Balmer & Gerber, 2018; Kakegai, 2021). Some experiences have been adopted and transferred cross-border, such as Mietshäuser Syndikat in Germany (Hölzl, 2022). Other challenges include the need for infrastructure adaptation in view of an ecological transition. Last but not least, vulnerable communities may face barriers due to race, ethnicity, gender or socio-economic status (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University 2022, p. 3). The COVID-19 pandemic has made the need for affordable housing more apparent (Shoag 2019; OECD, 2020; Shroyer & Gaitán, 2019; Florida, 2019).

Inquiries regarding the emergence of these phenomena hint at the rise in self-managed housing since the 2008 crisis, arguing that the latter has prompted civil society to engage in collaborative partnerships (Czischke, 2018) or community-led arrangements (Mullins, 2018). Besides, the growing number of initiatives is hypothesised as the internationalization of social movements in the age of social media (Mullins & Moore, 2018). Studies on collaborative or community-led housing have led to the exploration of practices at various levels: the organisation at the micro-level, multiple stakeholders’ partnerships at the meso-level and policy and welfare regimes at the macro-level (Mullins & Moore, 2018). The phenomenon is presented in the following three typologies: a) cooperative self-managed housing, according to the level of participation and inclusion (Tummers, 2016); b) collaborative housing, according to the internal level of collaboration and with external stakeholders (Czischke, Carriou & Lang, 2020); and c) a regime of sharing and tenure, according to value orientation, such as anti-capitalist, non-binary or multiethnic perspectives. Nevertheless, the third methodology does not facilitate the analysis of the enactment of values or the extent of participation in internal management processes (Griffith, Jepma & Savini, 2024, p. 138). As early as 2009, Lawson had already advocated for further research “at the micro-level operation of cooperatives and their sense of distributive social responsibility, the role of informal urban networks in policy making and the role of the local state in land and housing policy” (Lawson, 2009, p. 46, 64). The case study methodology (Yin, 2017) is used to explore motivations and practices expressed and conveyed by the members of housing cooperatives. Section 1, on theory, is followed by Section 2, on methodology. Section 3 presents the findings of the qualitative analysis, followed by concluding remarks, references, Annex 1, with key dates and awards of visited cooperatives, Annex 2, with photos taken during the visits, and Annex 3, with the list of shared spaces and practices.

1. Theory

Neoliberalism has promoted housing as a commodity and individual housing ownership as an investment vehicle for wealth (Aalbers, 2016, 2017; Bourdieu, 2005, pp. 10-12, 90, 224-225; Dewilde & De Decker, 2016, pp. 2-3). This approach has led to market failure with increasing inefficiency, inequality and divergence between offer and demand in housing. “The dismantling of housing policy leads to decentralised solutions” at lower levels, such as the cantons in Switzerland (Balmer & Gerber, 2018, p. 369). Initiatives towards decommodification are observed, and the second or counter-Polanyian movement would provide an explanation for the current efforts of civil society to decommodify housing (Capoccia, 2015; Lang, & Novy, 2014; Wijburg, 2020). A case study of five Swiss cities' policies on non-profit housing shows that decommodification occurs at the intersection of the economic, socio-political and ecological spheres, with the aim of achieving autonomy from the dominant property-driven economy (Balmer & Gerber, 2018, p. 381). Balmer and Gerber conducted interviews with representatives of public administration departments, associated organisations, and political parties (Balmer & Gerber, 2018, p. 368), but not with residents - owners themselves, as this article does, allowing autonomy to be understood as a motivation and goal constructed through commoning (Stavrides, 2015, p. 12; 17). This article draws from Polanyi and Ostrom to explore housing cooperatives members’ motivations and practices. Following Polanyi, decommodification should not be viewed as a matter of being in or out of the market but the of market society. First, a market should not be confused with the current market economy that transforms land, labour and money into fictitious commodities (Polanyi, [1944] 2001, p. 76). The removal of fictitious commodities concerns only the current market; “the end of market society means in no way the absence of markets” (Polanyi, [1944] 2001, p. 260). A market economy can only function in a market society defined as a society shaped to strive first and foremost for profit (Polanyi, [1944] 2001, p. 60; 257). where social relations are embedded in the economic system (Polanyi, [1944] 2001, pp. 257-258). In a counter-movement towards decommodification, the market economy is reembedded in social relations, instituting a “human economy, then, embedded and enmeshed in institutions, economic and noneconomic” (Polanyi, 1957, p. 250). Society institutes the economy through patterns of reciprocity, redistribution and exchange, and the economy may be defined by the pattern that is prevalent. In a human economy, reciprocity uses redistribution and exchange as subordinate patterns (Polanyi, 1957, pp. 253-255). In The Great Transformation, Polanyi discusses cooperatives, cites Villages of Cooperation and mentions the Builders' trade union (Polanyi, [1944] 2001, p. 177). The practical resolution of problems of everyday life, such as housing, could be achieved by transcending the limitations of the market economy, without sacrificing either individual freedom or social solidarity (Polanyi, [1944] 2001, p. 176).

Efforts towards affordable housing include housing cooperatives as a legal, non-speculative form of shared home ownership that is self-managed. Cooperatives are characterized by joint ownership, mutual help, democratic control and management, adhering to the Cooperative Principles.1 Cooperative housing is a type of housing where property is jointly owned. It empowers member families and residents as they are responsible for their decisions on the conditions, cost and quality of their housing (Sazama, 2000, p. 574). Housing cooperatives self-decide collectively their own norms and rules in terms of entry, participation, leaving the cooperative, usage and sharing, management and alienation or disposal. In addition to offering shared spaces that are self-managed, cooperatives aim to provide five housing conditions: affordable housing in terms of cost, sustainable housing in terms of long-term supply within the housing market, access to housing especially for vulnerable residents, housing ownership and rent control to prevent eviction and exclusion, and good governance practices (Skelton, 2002). Research shows limitations related to a) the level and type of capital that members may have to fully take part, b) regulatory constraints, and c) path dependent trajectories leading to re-commodification (Sørvoll, 2013, p. 25; 417; 469; Sørvoll & Bengtsson, 2018; Ferreri & Vidal, 2022). Other studies have shown a large array of benefits such as tenure security and higher levels of social cohesion (Haffner & Brunner, 2014; Davis, 2006, Gulliver et al., 2013; Lawton, 2014). Elinor Ostrom affirmed that “some of the most imaginative work on enhancing urban neighborhoods relates to helping tenants of public housing projects acquire joint ownership and management of these projects. This is a shift from government ownership to a common - property arrangement” (Cole & McGinnis, 2015, p. 53).

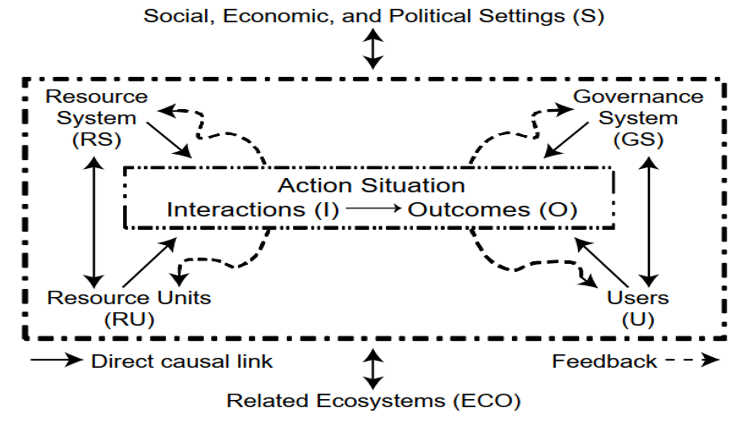

Building on Polanyi’s work, Vincent Ostrom links democracy to the idea of the commons, while Elinor Ostrom builds a theory on the commons through the most comprehensive number of case studies to date, which won her the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009. First, Ostrom explains how the capacity of actors to self-manage their situation by working together reduces the risk of a "tragedy of the commons" as posited by Hardin (1968). Second, Elinor and Vincent Ostrom advise to expand the concept of the commons to housing and urban renewal (Cole & McGinnis, 2015, p. 53; 104). To Ostrom, embeddedness is a strategy for coproduction and a better means to solve resource problems, by enhancing the capacity of those directly involved in local conditions to organize themselves into nested enterprises, improving the residents’ ability to address their own needs (Cole & McGinnis, 2015, p. 56). Similarly to Polanyi, embeddedness entails social action that becomes embedded through the formation and management of institutional arrangements. Third, for Elinor Ostrom, a conceptual model is useful to “make precise assumptions about a limited number of variables in a theory that scholars use to examine the formal consequences of these specific assumptions about the motivation of actors and the structure of the situation they face” (Ostrom, 2009). Elinor Ostrom, in her Nobel Prize lecture, proposes a Social-Ecological System (SES), as seen in Figure 1 below, to guide the analysis of common pool resources, explaining that boundedly rational actors interact through monitoring, conflict, lobbying and self-organisation. Resources are placed on the left, while results with impact on governance and users are displayed on the right. Outcomes are mentioned in terms of sustainability, such as the regeneration of biodiversity and the resilience of an ecological system. Both interactions and outcomes in the action-situation box are separated from users. However, in practice, actors self-manage the situation, deciding and monitoring their own rules and norms.

Elinor Ostrom’s coproduction model, first conceptualized in 1981, refers to a polycentric system that is exemplified by decentralized social action increasing the endogenous levels of trust and reciprocity (Parks et al., 1981; Ostrom, 1990; 1996; 2005). Rules and norms are established and reinforced to the extent that they are shared and maintained through coproduction (Ostrom, 2005, p. 65). Polycentric governance is linked to the concept of nesting because in successful commons, if a common pool resource is closely linked to another large one, governance structures are ‘nested’ with each other at one or more levels, and common principles of management run throughout like patterns. (Helfrich, 2012). Vincent Ostrom connects democracy and non-profit cooperatives in the arrangements in local communities, from conception to feasibility studies, to physical works, where the longer term results depend on how their enterprise is led and managed. If operated as a nonprofit cooperative enterprise, generated profits would turn into economic returns to present and future property holders (Ostrom, Tiebout & Warren, 1961, p. 209; 211).

Thus, a commons is neither a form of ownership, nor the resource itself or pure management. A commons is about self-managed commoning, understood as social practices “actively produced, maintained and expanded through cooperative, collective action” (Helfrich, 2012). For Bollier and Helfrich (2015), a commons creates a system to manage shared resources through acts of mutual help, conflict and mediation, negotiation and dialogue, communication and experimentation. Besides, a commons is defined through bundles of rights. These cover five types of rights that members using a common pool resource might enjoy: 1) access - the right to enter a specified property; 2) withdrawal - the right to harvest specific products from a resource; 3) management - the right to transform the resource (such as land and habitat) and regulate internal use patterns; 4) exclusion - the right to decide who has access, withdrawal or management rights; and 5) alienation - the right to dispose of or sell any of the other four rights (Ostrom, 2009, p. 419; Schlager and Ostrom, 1992).

2. Methodology

Lawson, Haffner and Oxley (2010) propose to study real world experiences in order to interpret and recontextualize the housing phenomena by looking for a plausible and justifiable set of explanatory concepts (Lawson, Haffner, & Oxley, 2010, p. 5). Guided by a constructivist epistemology, this research analyses in particular “the action and interaction strategies of the actors in the field, whereby special emphasis is laid on their intentions and goals” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, pp. 158-159). The exploration of motivations and practices in housing cooperatives in Geneva and Zurich follows the case study method (Yin, 2017). There are different types of active cooperatives in the housing sector. Two of them are noteworthy in Switzerland: construction or building cooperatives2 and housing cooperatives of dwellers. The present study focuses on the latter in Geneva and Zurich: La Rencontre, CODHA Rigaud, OuVerture, Luciole, and Kalkbreite (see Annex 1 for the dates of foundation, construction and awards). Visits took place in September 2023. Interviewees gave informed consent to interviews, to the visit to the cooperative premises and to the recording of dialogues.

Primary, first-hand notes and visual data, photographs and videos were collected during the visits. Semi-structured interviews were conducted using a 12-question questionnaire, with an open dialogue to elicit information regarding the participants' life experiences, motivations and practices. The full text of each interview was shared with the interviewee for feedback. I stayed for a short time at the residence of a group registered as a housing cooperative and expecting to enter their dwelling in 2027, as well as at the Kalkbreite Guesthouse in Zurich as visitor. Interviews were coded and analysed with the Atlas.ti CAQDAS (computer aided qualitative data analysis software) applying grounded theory methodology (Friese, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Strauss, 1987).

3. Findings

3.1. Overview of cooperative housing

The Swiss welfare regime is characterised by a mixture of liberal and conservative traits, and its housing system is dominated by private for-profit rentals (Lawson, 2009). Swiss are renters in their majority. “At the end of 2021, 2.4 million households in Switzerland (61%) lived in a rented or cooperative dwelling” (FSO, 2023a). The urban system of Switzerland comprises 55 core cities and their respective functional areas and is characterized by a high degree of integration and polycentricity, which mirrors the country's federal and decentralized political structure (Rérat, 2012, p. 119). Peter Gurtner, former director of the Swiss Federal Office for Housing, and later president of the Bond Issuing Cooperative, explains that there is no legal definition of social housing, but institutions that "apply the cost-rent principle and respect the principles of a charter, as well as fulfil legal obligations" are recognised as such (Gurtner, 2014, p. 32). Cooperative housing is also called affordable, nonprofit, not-for-profit, and of general interest.3 Swiss affordable housing provisions consist mainly of housing cooperatives, diverse income levels and lifestyles (FOH, 2006, pp. 37-39). Rental expenses in cooperatives are lower than other rental rates, from 20 to 30%, reaching 60% lower in Zurich and Geneva.4 The participation of low-income members in cooperatives is supported through cost-rent housing and rent subsidies (Balmer & Gelber, 2018, p. 365). In 2014, there were 1700 housing cooperatives, with fewer than two dozen owning more than 1000 dwellings each (Gurtner, 2014). The opening in 2014 of the Kalkbreite cooperative raised widespread interest after winning the public competition with their proposal. It is a building area with 88 flats organized in clusters, ‘joker spaces’ that can be added on, communal areas as well as cultural, catering, retail and service premises for 256 residents, providing 200 jobs.

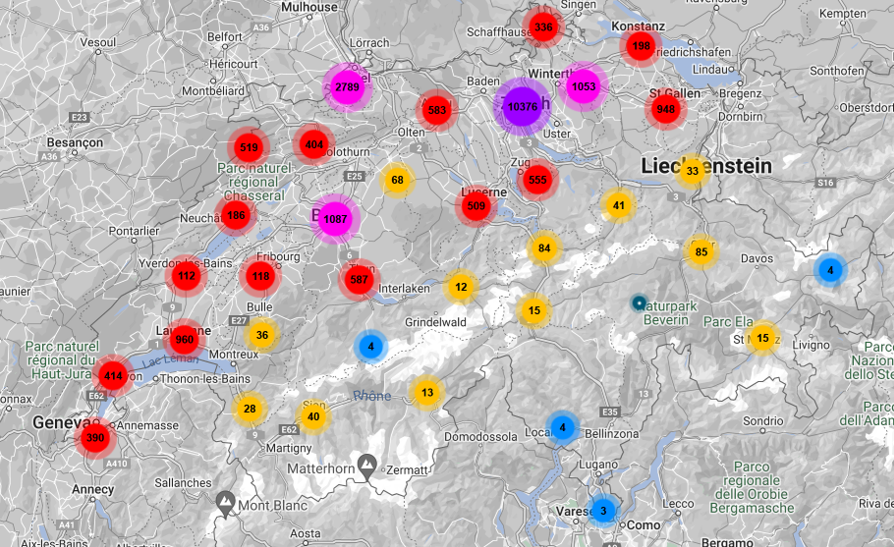

The Swiss Federal Constitution does recognise the right to housing but this is not legally binding, while cantons do not incorporate this right into their constitutions, instead handing over responsibility to the municipalities (Drilling et al., 2021). Cantons play a key role in offering the right to use public land or emphyteusis. Some municipal authorities prioritise non-profit initiatives, which are subsequently financed by private actors, including cooperatives (Rérat, 2012, p. 120), but this only applies to publicly owned land. Today, housing cooperatives play a significant role in the supply of affordable housing, yet a modest one in the overall Swiss housing sector. They are present across the country but more significantly in the large urban centres, as shown in Figure 2. They represent 22.9 % of all owners of rented dwellings in Zurich from 2020-2022 (FSO, 2023b).

(FOH, 2022) https://genossenschaften.wbg-schweiz.ch/

Figure. 2 Locations and numbers of housing cooperatives in Switzerland 2022

There are few systematic studies of Swiss housing cooperatives. The first comprehensive study since 1969, based on censuses and a survey of 1400 housing cooperatives, was conducted by Peter Schmid (Schmid, 2005). Swiss housing cooperatives are considered non-profit organisations with the social purpose of providing the population with affordable housing.5 However, the mission of each cooperative, which is not only economic but usually includes a social, socio-cultural and/or political mission, is defined by the member-owners themselves. The five cantons of Zurich, Bern, Lucerne, Basel City and Geneva account for 70% of all Swiss cooperative housing. According to a Swiss Labour Force Survey of 2002, persons with lower incomes tend to reside in cooperatives, which then contribute to the provision of housing for low-income households to a substantial degree. The average size of a cooperative board was 5.8 members (Schmid, 2005). There was a predominance of small cooperatives, facilitating the realization of the objective of collective ownership and communal living by members with little equity. A significant number of small cooperatives had been set up in the 1980s and 1990s, characterized by a higher level of member involvement, bringing about more social and community benefits and facilities, and showing a greater appreciation of the cooperative principles, compared to those established earlier (Schmid, 2005). A newer study confirms these characteristics as a new generation of housing cooperatives since 2000 (Duyne Barenstein & Koch, 2022, p. 5).

3.2. Brief history

The first Swiss housing cooperatives emerged between the 19th century and early 20th century. The first attempt to establish a housing cooperative, which ultimately proved unsuccessful, was initiated by Collin-Bernouilli in 1867 (Ruedin, 1994, p. 4). Switzerland has not been immune to international trends in public policy, whether in the 19th century, with the rise of the cooperative movement, or more recently with the trend towards a reduced role for the state (Lawson, 2009, p. 61). Sazama mentions a similar situation in the United States, where cooperative housing was first led by trade unions seeking decommodification and by ethnic groups of immigrants (Sazama, 2000, p. 1; 576-578; 599). In the US, some high-income families were among the pioneers in establishing housing cooperatives but only those comprising immigrants or workers were able to survive the 1930s Great Depression (Sazama, 1996, pp. 1-2). When the need arose after the First and Second World Wars, Swiss housing cooperatives contributed to reconstruction. As the socio-economic structure evolved and part of the working class attained middle-class status, their membership became more diverse, including the middle class (Duyne Barenstein & Koch 2022; Duyne Barenstein, Schindler & Schlinzig, 2023). From less than 1500 cooperatives in 1919, the number grew to around 6500 in 1945, and 9123 between 1946 and 1960, the peak of the movement (Curtat, 2013). It was only in the 21st century that they have regained ground (Duyne Barenstein, Schindler & Schlinzig, 2023, p. 584).

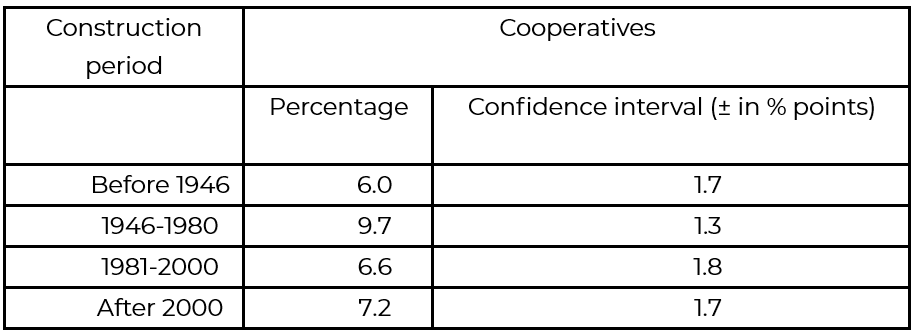

The current legal framework is provided by the Federal Law of 2003, offering three federal policy instruments, a third of which in direct support is suspended due to fiscal constraints (Swiss Confederation, 2003). The two others provide indirect support through guarantees, to facilitate the dissemination, exchange, and mutual learning by supporting the activities of the non-profit housing associations in the fields of training, advice and information. Additionally, it informs about exemplary housing projects for their innovation in terms of sustainability, quality, utility value and location, thereby increasing the visibility of sustainable practices and the awards received by cooperatives. From 2000 to 2023, as shown in Table 1, cooperatives grew to the rate of 7. 2%, higher than in previous periods (6.0% and 6.6%), with the exception of post WWII (FSO, 2023c).

Table 1 Cooperatives: type of owners of rented dwellings. Growth by construction period

Source: FSO, 2023c.

3.3. Social mobilization for housing as commons

Civil society, in both French and German speaking regions, has been mobilizing for housing cooperatives. Interviewees emphasized recent referenda in favour of more cooperative and affordable housing: in Zurich, in 2011 (successful), nation-wide (failed) and Geneva (legally approved but not yet voted). In the second half of the 20th century, housing cooperatives had not played a significant role in politics (Koch, 2021, p. 28). In recent decades, as the market failed to provide affordable housing and the federal state withdrew from supply-side policies, social mobilisation has led to many citizens' initiatives at the local level (Balmer and Gerber, 2018). Among them, many new housing cooperatives of residents have been created, enjoying high public support (Duyne Barenstein and Koch, 2022, p. 7; Balmer and Gerber, 2018).

Schmid (2005) establishes a connection between the newer and smaller cooperatives and increased member engagement in cooperative values. In November 2011, a local referendum in Zurich resulted in three-quarters of the population approving a mandate that affordable nonprofit housing should reach 33% of the city's rental stock by 2050 (Hofer, 2019, in Khatibi, 2022, p. 3). In February 2020, a nation-wide referendum was voted in favour in five Cantons, but rejected by a majority due mainly to the rural vote (Koch, 2021). This was followed by 8200 signatures for a new referendum ‘For + housing in Cooperatives’ in the Canton of Geneva, approved by the Council of States.6 Lately, 90% of participants in the Geneva 2050 Consultation supported housing cooperatives.7

This should be put in the context of a broader debate on sustainable transition (Swiss Federal Council, 2021). Indeed, many of the cooperatives’ awards highlight innovations in renewable sources, construction, soft mobility, and the use of land. Cooperative members exchange knowledge with academics and the wider civil society in international meetings. In 2015, the first Alternatiba Leman gathered 30,000 participants and hundreds of organisations in Geneva.8 In 2022, the Second Global Housing Cooperatives Symposium took place in Zurich and included a visit to Kalkbreite. Participants came from the USA, UK, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and Asia (Housing Cooperatives International, 2022). Several cantons are approving sustainable measures. A 26 September 2021 vote in Bern was followed by a vote on 15 May 2022 in Zurich with a 67.12% majority approving a constitutional amendment codifying a target to achieve net zero or greenhouse gas emissions. Other cantons are working on similar proposals.9

At the local level, the manner in which civil society strives for a commons may be serendipitous. In Geneva, the cooperative La Rencontre I visited is part of a self-managed neighbourhood. The Community of Residents is called ‘Ilôt 13’. Its head office, the Maison des Habitants (MdH), houses artists’ workshops. During the renovation in the 1980s, the place was handed over still unfinished to the locals, who worked collectively to finish the refreshment area and the Écurie, including interiors, façades, wooden frames and shutters. The City of Geneva provided an initial investment of CHF 500,000, while the residents' association secured a further CHF 220,000 from Alternative Bank to supplement their own savings, which were invested in equity to the value of CHF 40,000. In April 1986, facing potential demolition, the Fanfare de l'îlot 13 of about twenty musicians began to perform in processions, schools and other venues. Woodwork and repair workshops were set up as ‘Atelier 15bis’. Since October 1986, the MdH Centre has housed workshops in stringed instrument making, screen printing, sculpture, painting, a recording studio, two rehearsal rooms, a dance studio, a carpentry workshop, and a cellar for rock concerts. Decisions are made by consensus. The entire neighbourhood has a General Assembly at the buvette on Mondays and, for that reason, it is closed on that day. There are subgroups for the Internet, for the kitchen, for an oven bread among others (Interviewee, Geneva, 640, p.6).

The history of Ilôt 13 goes far back. The Grottes, the area of Geneva where La Rencontre is located, has a long history of labour movements. After being attached to the city of Geneva in 1850, this was a workers’ area. After the meeting of the First International in Geneva in 1867, residents created producers’ and consumers’ cooperatives. By 1928, the local authority had formulated a plan to demolish it and taken steps to prevent any renovation work. In 1971, the local population opposed a plan to transform it into a satellite dormitory suburb and started a collective action to brand the area as a squatters' camp. The district was subdivided into blocks at the request of the local population, Ilôt 13 being the largest. A video by RTS, the Swiss French speaking television, shows how squatters and cooperative members lived together in 1995.10 As an interviewee explained, their participative renovation and engagement in solar panels, which they built themselves, showed how to inhabit the city in a decommodified manner. Members of the community association and an architect presented the experience to a Conference in 2006 (Gisselbaek, Haefeli & Hollmulle, 2006). Emancipatory practices, reproducing forms of cooperation through sharing, include open areas of crossing, from the inside to the outside. Commoning is a complex process beyond spatial production whereby “the people involved construct a community of equals because they choose to define at least part of their life autonomously and in common” (Stavrides, 2015, p.12; 17). Stavrides’ view of commoning practices are observable in the history of the Ilôt 13 in Geneva, where the solidarity-based practices are self-managed by the neighbourhood, while in each cooperative they are self-managed by the member - dwellers, nested within the former. It should be noted that there are other housing cooperatives in the same Ilôt 13.

The social mobilisation that led to the creation of Kalkbreite in 2007 was also neighbourhood based. In 2014, its members moved in. Starting with an old man in the neighbourhood, a small group of five or six people began to meet, reaching the number of 50. They came up with a project called harp - ARPA, responding to two non-negotiable constraints in the public call. The first one was that the 30 tram depots had to stay. This meant they had to build on top of them. The second rule was to offer as many spaces and shops to the neighbourhood as possible.

3.4. National and international exchanges

The housing cooperatives visited for this study receive visitors of various types. Many visitors are local and national but there are also international ones through international meetings of cooperatives, architects and policy-makers. In Geneva, Luciole has hosted whole classes of primary, secondary and university students since 2017: “We provide them with information and evidence to encourage a re-evaluation of their perceptions of housing, costs and opportunities. However, on each occasion, they express their astonishment at the initiative” (Interviewee, Luciole, Geneva, 936, p.51). Other groups including housing cooperatives have visited this cooperative since 2009. Kalkbreite maintains a committee of volunteers whose role is to guide visitors according to their expressed interests, such as architectural, organisational, or social aspects of the site. For Luciole, the experience of interacting with the Belgian Bouwmeester11 stands out as particularly noteworthy.

“He visited Luciole with the objective of exchanging ideas on how to counsel the Belgian government on housing policy. Furthermore, his entire team returned after his visit in October 2023. There were 50 Belgians in the garden, a delegation comprising several teams of public policy experts… I was invited to engage in a discussion with a Belgian lawyer to ascertain the applicability of legal provisions and to have it transcribed for publication in a Belgian construction magazine. However, what I found particularly rewarding was the realisation that our efforts may have a tangible impact on the potential future development of cooperatives in Belgium. It was a highly satisfying experience” (Interviewee, Geneva 936, p.13).

In France, the Order of Architects of Ile-de-France organised a seminar on cooperative housing and Zurich on 24 October 2019, and a debate on 21 November 2019. 12 The 2020 Exhibition The Housing Laboratory stated that cooperatives had become a benchmark for residential architecture.13 In 2022 in Barcelona, Swiss representatives of cooperatives met with Spanish local authorities, architects' cooperatives and the German Goethe Institute to discuss clusters as part of a cooperative model.14 At the 2021 Venice Biennale of Architecture, the exhibition Cooperative Conditions, A Primer on Architecture, Finance and Regulation in Zurich proposed eight conditions to explain the commitment to decommodification, of which the first is sharing, “not only through joint ownership and collective decision-making but also the disposition to share spaces”.15

3.5. Establishing a housing cooperative

Members first register the housing cooperative as a legal person, and then look for the right plot of land to build their project. First information about a housing cooperative is found online.16 With regard to the right of disposal, this type of housing is not subject to speculation and cannot be sold for profit. Cooperative members can enter and leave, having the right to withdraw their personal funds and move to another home (cooperative or not). Rents are at cost. Revenue from shops, guesthouses or offices in the cooperative's properties is reinvested in the cooperative's mission. The initial rent may appear high due to construction costs, but on average it is 20% lower than the market rate. Interviewees confirmed that their rental costs are around 40 % lower than the market. In Kalkbreite, as in the rest of the neighbourhood, rents have not increased at all since the opening. In the case of La Ciguë in Geneva, part of Ilôt 13, the rent is 55% lower than the market rate according to World Habitat (see Annex 1).

In agreement with the former director of the Federal Office for Housing (Gurtner, 2014), and the Swiss Federal Council 2024 Action Plan, in its Article 6 (Swiss Confederation, 2024), interviewees made clear that land access and affordability were major issues to address the housing shortage.17 In 2014, Gurtner had noted that for nonprofit housing “just to maintain the modest market share already requires a tremendous effort(...) The biggest impediment to achieving this lies in the lack of suitable land” (Gurtner, 2014). The trend to promote smaller housing cooperatives continues, sometimes besides a larger one. These are cooperatives built near a larger one for reasons of scale and nesting (Helfrich, 2012). Examples are Luciole and Equilibre that share various systems of car sharing and guest rooms; and OuVerture and Quercus to be built in Presinge (Geneva). A recently approved Localised Neighbourhood Plans (PLQ) in Geneva, a new requirement before obtaining permission to build, highlights the social added value of housing cooperatives for the community, particularly their shared spaces that enhance the quality of life in the neighbourhood, such as artists' and craftsmen's studios, community halls, crèches and kindergartens, intergenerational meeting places, and community services to the population at large.18

3.6. Funding a housing cooperative

Funding comes from cooperative members, followed by bank loans, their own instituted funds and foundations. Support stems from federal, canton and municipal instruments, in some cases implemented on a fiduciary basis by cooperative federations and nonprofit housing architects. First, projects are funded by cooperative members’ own equity, accounting for 10% of total equity at least. This is followed by credit and/or small loans from a revolving fund.19 The members’ investment20 gives equal power in control and self-management to each member, namely, one person, one vote.

Schmid (2005) shows that 90% of all cooperative dwellings of the 78% responding housing cooperatives had benefited from nonprofit funding. About half of these had received support from the federal government. The majority had received support from the public sector during the construction phase, but only a limited number had received federal basic grants after 1975. The most common source of funding has been land with building rights (46%), followed by the repayable federal land grant (41%) and loans from the revolving fund (35%). This is followed by subsidised cantonal and/or communal loans (19%), loans from the solidarity fund of the Swiss cooperative federation (17%), public sector guarantees (9%), mortgage guarantees (9%) and subsidised cantonal/communal land (6%) (Schmid, 2005).

On the basis of members’ equity, a cooperative obtains bank loans. In Zurich, about 80% of the value of local cooperatives is debt, most of it from banks. First mortgages cover 60-80% of development costs. There has been a Mortgage Guarantee Cooperative since 1956 with the objective of making non-profit buildings more affordable, supported by the federal government through the provision of back-up guarantees,21 which serves as additional security for the lender, allowing them to apply more favorable terms due to lower risk.

Since 1902, the Zurich Cantonal Bank (ZKB) set a legal obligation to lend to cooperatives. Since 1992, most cooperatives have also received second mortgages from the Pension Fund of the City of Zurich, which finance 14 to 34% of development costs. Both are private institutions, and their lending to cooperatives is backed by the City of Zurich. In Geneva, financing for the cooperative member’s investment can come from the 2nd pillar or a loan from the Canton, repayable over 5 years. In these cases, the first step with members’ equity may be less than 10 % of total equity.22

Cooperatives build their own solidarity funds both within individual cooperatives and at the level of federations, usually collecting 10 CHF per member, like ABZ23 and Kalkbreite in Zurich. 24 The Federation of non-profit housing architects and constructors25 provide assistance through three foundations to its members, which must meet the requirements as a non-profit organisation, including the signing of its Ethical Charter.26

At the federal level, since 1990, indirect support is given through federal guarantees to bonds issued by the Swiss Bond Issuing Cooperative - BIC, backed by public federal guarantee. Created in 1990, the BIC is a cooperative whose members are housing cooperatives and other nonprofit builders, with a Central Issuing27 that “raises funds on the financial market (...) through bond issues and private placements. Its issues are guaranteed by the Swiss Confederation, and it has the highest credit rating in the rating guide of the Zürcher Kantonalbank ZKB”28. It issues the bonds carrying AAA rating in its own name, on behalf of its 300 members. The BIC bond process institutional framework is shown in Figure 3.

Since its creation and until January 2024, BIC has issued 96 bonds with a total volume of 8.03 billion CHF.29 The volume of loans shows an upward trend between 1990 and January 2024.30 Interest rates on these loans are one percent lower than fixed-rate mortgages of the same term and tend to be slightly lower than all-in costs. The guarantees cover up to 90% of the cost. This indirect federal instrument provides a working capital fund managed by the non-profit housing federations operating under performance mandates. The bonds in question are in high demand due to the federal guarantee (FOH, 2006, p. 60). In addition, there is a Revolving Fund managed on a fiduciary basis by the major Swiss federations of nonprofit architects and cooperatives.31 Moreover, cooperatives work both with savings banks and a renovation fund earmarked for maintenance and repairs that is automatically funded by a fixed percentage of the rent.

3.7. Ethical Charters

Since the enactment of the Federal Law of 2003, it is obligatory that all nonprofit housing adheres to ethical charters. The Charter of non-profit housing constructors in Switzerland, signed in 2004, declares housing as a basic human need and its access at “an affordable price that is adapted to the needs of the individual is a fundamental right for every individual and every family”.32 The Wohnbaugenossenschaften Schweiz - WBG33, the Federation of Swiss Housing Cooperatives, requires the signature of its Ethical Charter to be able to apply for any funding.34 WBG has two types of members: 1000 full members that are non-profit housing cooperatives, nonprofit housing architects and constructors plus foundations in 9 regions, and 20 associate members, mainly communities and public institutions.

In Geneva, the 80 affiliated cooperatives to GCHG have signed its 2005 Ethical Charter.35 In 2020, they led a contest on how well members align with the Charter in four categories: living together, architecture, ecology and utopia for innovation and good living for the future.36 It had three juries consisting of a) experts chaired by Geneva State Councillor Hodgers, b) students of the Hautes écoles Spécialisées (HES) and c) the public through an internet vote.

Furthermore, every housing cooperative has its own ethical charter, which in turn may evolve in time. Some of the cooperatives we visited have their Ethical Charter at the entrance. In Geneva, Equilibre, the larger cooperative sister of Luciole, has had two versions of its Ethical Charters, the first version in 2015, and the second in 2020. The former mentions quality of life, sustainability through reduced impact on resources, respect for the environment, renewable energy and resource conservation, participation and cohesion through integration, bonding, ethics, different generations, and respect for cooperative choices and shared spaces.37 The modified Charter mentions seeking a balance between individual and collective responsibility, collective intelligence, cooperation, mutualization, promoting individual ownership while strengthening social ties, creativity, solidarity, cooperative values and equitable distribution of wealth. Goals include an economy of the commons (common good), affordable and sustainable neighbourhoods, promoting participatory cooperatives, artisanal knowledge in construction systems, promoting activities that respect all forms of life, preserving biodiversity, affordable housing and facilitating citizens’ initiatives. 38 The Ethical Charter of Quercus, a cooperative that will be built besides OuVerture in Presinge in 2027, concentrates on sustainable issues such as renewable energy, soft mobility, recycling and a society at 2000 watts, while mentioning values of solidarity, intergenerational solidarity, sharing common spaces and activities.

3.8. Engaging in cooperative housing: motivations

Interviewees’ motivations highlight belonging, a sense of empowerment and a commitment to group experiential innovation. Interviewees share some common life moments: moments of change. They become cooperators as they are forming a family, relocating to another city or country, experiencing a change in family life, or retrieving childhood memories of growing up in a cooperative. The period between the formation of the housing cooperative and the members’ entry into their new dwelling lasts between seven and twelve years. Thus, motivation needs to be sustained over a long period before they enter their cooperative. Interviewees explain that members work in various sectors, including manufacturing, services, education, research and the arts. Some are self-employed professionals, such as hairdressers. In some cases, members have been union members. Individuals seeking to join a specific cooperative need to apply, propose themselves or receive a notice from mailing lists or through acquaintances. It is common for members to remain in the same cooperative for an extended period. Members volunteer to serve on committees and the cooperative board. Housing is felt as shared homeownership, as a living space that is more secure due to factors of affordability, accurate knowledge about the quality of the construction, the power to define and monitor rules of living and sharing, and the ability to influence living and transportation conditions from young to old age. Self-management, participation, sharing and defining common spaces are essential for all interviewees.

Some interviewees talked about displacement, arguing that they live in a model based on cost to rent, which prevents displacement because the original people can stay, as rents remain lower than any market rates. This would be a question for further research. They express that they can accommodate people with limited financial resources through solidarity. They endeavour to gain access to land on more favourable terms through the utilisation of foundations, yet are aware that these fail to meet their needs. Members learn from other cooperatives about collective innovation, whether in solar panels at La Rencontre, dry toilets and materials at Luciole and OuVerture, or architecture at Kalkbreite. They travel to other regions for such visits. A major motivation is to take control of their common housing and lives: “We rent our houses to ourselves(…) You don't have to put up with the whims of a landlord who suddenly wants your house back. You know in your statutes what to do if something happens” (Interviewee Geneva 11, p.4). Cooperative members build their bundle of rights by embodying their normative expectations into their rules. Following Polanyi, normative expectations become embedded into a human economy. Cooperative members speak of housing as shared living that reduces uncertainty, vulnerability and provides opportunities. In pursuing the goal of decommodification in housing, they are able to establish a sense of belonging and create a space in which they can build their own lives.

3.9. Building a commons: practices

As Schmid (2005) and the 2021 Venice Biennale exhibition39 show, there has been a shift of housing cooperatives towards a more participative approach in self-management and sharing. Decision-making tends to be horizontal, whether on design, budgets, materials and sustainability, but also ethics, rights and practices. The decision-making process takes time but is viewed as a necessary component to build trust. Decisions tend to be made by consensus and are recorded in writing. When opinions cannot be bridged, there is a vote. Youth and children have their own committees and present requests and proposals to the General Assembly.

Conflict is understood as unavoidable, and every cooperative decides the rules on how to deal with it. They tend to leave first private matters to be solved directly among members, followed by mediation. In Zurich, at Kalkbreite cooperative, the decision has been to have an ombudsman. “An internal ombudsman's office is available for conflicts that cannot be resolved by the tenants themselves. This person is (re-) elected annually by the General Assembly. (Interviewee, Kalkbreite, Zurich, 666, p.1; 33 - 34).

The criteria for the allocation of apartments are set out in the rental rules formulated through a participatory process and subsequently approved by the general assembly. In Kalkbreite, an independent rental committee is responsible for the selection process. Ultimately, the decision is made by the immediate neighbours (in each cluster). In the case of groups such as students, residents can select their own flat mates without the involvement of the rental committee (Interviewee, Zurich 605, pp. 95-326).

At Kalkbreite, if there are too many members with the same characteristics, the cooperative uses an algorithm identical to that used by the city authorities, although the final say belongs to the cooperative clusters of smaller groups of cooperative members. This is to care for vulnerable groups such as pensioners, the elderly, refugees and women. Every cooperative decides the number of working groups and committees, and a common practice is to care for others, in particular children and the elderly, such as a committee on ageing, and parent shifts to cook for all children going to school.

Cooperative members choose the nonprofit architect, visit other cooperatives and exchange regularly in larger meetings. They have designed rooms, mezzanines for children (in Geneva) and movable panels (in Zurich), to mention a few examples, to suit members’ needs. At Kalkbreite, for every nine people, there is a common living room, namely for those living in the surrounding cluster, with a full kitchen that is a communal space. In addition, members have a large kitchen with a cook supervised by the public regulatory authority, which they have to clean in teams by volunteering every three months. Each member has a compact kitchen unit in his or her apartment, consisting of a sink, a modest fridge and a wastepaper basket, but no oven, washing machine or dishwasher. The latter are located in the common room (Interviewee, Zurich, 639, pp.81-165). The management of some commercial premises in larger cooperatives, such as the Kalkbreite cinema, may be delegated to third parties. This requires further research, as Polanyian movements of commodification and decommodification may occur simultaneously, to analyse which pattern (reciprocity, redistribution or market exchange) prevails over the others.

Solidarity networks may be observed through formal or informal arrangement. Kalkbreite hosts both an office to provide refugees with information and Greenpeace Switzerland, since 2014.40 I met an Afghan refugee from the same cluster where my guide is living. Cooperatives’ common rooms are open for use by nonprofit associations. In La Rencontre in Geneva, the common room for their general assembly is used by the fair-trade association Magasins du Monde. Observed common activities and spaces include those in Schmid (2005) but new ones appear. The following stand out (Annex 3 mentions the full list):

Shared rooms: a) common rooms: for the general assembly, rooms for external visitors, such as friends and family; b) guest rooms: some decide they can reserve a few times a year, some up to five days each time, for family or friends; c) craft and repair rooms for hire or for free reservation, including to work with metal, bikes, wood, and music room, which may be reserved on paper, internet or with a QR; d) working rooms, studios and co-working.

Green sharing: common compost, may include water management; gardens, vegetable and fruit ones, shared and/or parceled; spaces for the public to sit in green spaces, eat, study; d) spaces for celebrations, pizza ovens, bread baking.

Repairing and recycling: small repairs free of charge, exchange spaces for repairs, donations, services; billboards as a means to give away objects, or offer services.

Funding: deposit fund, reserve funds, solidarity funds; financial assistance in emergencies.

Environment: solar panels; compost; water management; dry toilets.

Mobility: soft mobility as an option or as requirement (e.g., rejection of parking cars except for disabled members); free bikes.

The photos in Annex 2 show examples of how the members of the cooperatives visited have designed these types of spaces. Interviewees speak of their results in terms of sustainability and innovation such as La Rencontre’s self-built solar thermal systems, which has since been adopted throughout Switzerland, resulting in a 10% increase in installations nationwide. CODHA Rigaud members, after winning the competition call for urban projects by the local city council, have built six buildings with a total of 49 flats, including a cluster and 3 guest rooms, seamlessly integrated in the neighbourhood through green areas. It is the first self-sufficient project in Geneva with the Minergie P Eco® label, producing 90% of the electricity it consumes. In Kalkbreite, the incorporation of movable panels is an integral aspect of the architectural design, facilitating adaptability to the various needs of residents. This idea of adaptability is in opposition to the notion of mass housing. After being experimented in Kalkbreite, it was replicated in their follow-up project Hallenwohnen, completed in January 2021. The private and semi-private spaces are adaptable to changing needs, with the use of large open halls that feature collective basic structures and rollable residential towers (Khatibi, 2022). The process of nesting enables the formation of shared solutions. In Geneva, members of Luciole and Equilibre, two neighbouring cooperatives of differing sizes, have relinquished the use of private vehicles in favour of sharing car-sharing schemes. They have implemented various sustainable construction techniques, including the utilisation of prefabricated caissons filled with straw bales (manufactured in the canton of Geneva) for the insulation of the façade, earth plaster for the interior cladding, lime rendering for the exterior cladding, direct consumption photovoltaic panels, heat recovery for heating and hot water, and wastewater treatment. To put these efforts into context, a 2021 study by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office asserted that cooperative dwellings use more gas and oil sources as buildings are larger and equipped with oil or gas boilers; as well as more solar thermal and renewable sources, compared to others (FS0, 2021).

Concluding remarks

The personal motivations of members who were interviewed are influenced by a range of factors, including economic, social and ecological considerations. However, experiences observed suggest the same movement towards decommodification as the source of their social construction where reciprocity is the prevalent pattern (Polanyi, [1944] 2001), sustained by experiential practices striving to build a commons (Ostrom, 2009). The cooperatives which were presented here exhibited common characteristics, including self-management, voluntary participation, sharing of common spaces and similar patterns regarding their bundle of rights. Once cooperatives are formed and built, they cannot be sold on the market, nor can they become for-profit. Their representation of life experiences shows a will to work together to achieve affordability and adaptability of materials and spaces through practices of solidarity, mobility and sustainability. The encouragement of innovation appears to be correlated to the degree of trust (Putnam & Nanetti, 1994, pp. 139, 142, 148), which is a central aspect of a social dynamics based on reciprocity (Putnam, 2000, p. 19). The process of establishing trust through cognitive experience, such as in the construction of housing and the maintenance of relationships, serves to reinforce the notion of personal self-efficacy (Bandura, 2010). Consequently, members experience a sense of empowerment through practices based on reciprocity and sharing (Somerville, 1998). This is reinforced by the common spaces that members construct (Lawton, 2014, p. 217).

Members of cooperatives are able to access knowledge in a number of areas, including construction, ecological transition, training, such as cadastral reading, devising soft mobility solutions, as well as funding instruments, such as cooperative mortgages, cooperative bonds, solidarity funds and foundations. Since 2014, awards have enhanced their visibility but several instruments and practices date back to earlier decades, such as bond guarantees and mortgages. Housing cooperatives are between 20 and 55% cheaper than other options on the market. The foundation for this success can be attributed to social organisation, which is based on both ethical norms and self-management sustaining efforts of decommodification. It may be considered a coherent conceptual model built by experiential practices. The notions of the right to affordable housing and housing as a common good have gained more presence as a subject of public debate. In light of the fact that this is not a mass provision of housing and that the primacy of Swiss for-profit rentals is likely to persist, it can be argued that Swiss housing cooperatives may serve as exemplars showing that decommodification is possible, through a coherent set of bundle of rights, embedded ethics and self-management. A more comprehensive understanding of nesting practices (Helfrich, 2012) would help to better understand Polanyian movements. The potential for adoption abroad of some or all of their characteristics remains an open question and requires follow-up. Multidisciplinary dialogue among researchers in urban sociology, environmental studies and cooperative studies is recommended to study cooperative housing, to encompass a range of issues, including community empowerment, ecological transition, forms of labour, solidarity practices and inclusive urban renewal advancing the concept of commons.