1. Introduction

On April 25, I realised that I wanted to fight against existing poverty. I wanted a better life for all of us. I wanted people to have the same rights as everyone else. I was a revolutionary. (INT 1)

On April 25 1974, a coup carried out by the Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas - MFA) put an end to the longest European dictatorship of the 20th century, which had lasted 48 years under the leadership of António Salazar and - after 1968 - Marcelo Caetano. Thirteen years of colonial war in the ‘Overseas Provinces’ of Angola, Guinea, and Mozambique contributed to the creation of the Armed Forces Movement (Cardina & Sena Martins, 2018). The Carnation Revolution, led by MFA, opened the door to several types of labour and other social movements, such as strikes, protests, and occupations of production units (factories, farms, companies) and private and public housing. The movements were notable for the participation of industrial workers, agricultural wage earners, students, workers from the informal sector, and members of the armed forces, as well as the broad participation of women (Varela & Alcântara, 2016). PREC, Processo Revolucionário em Curso, an acronym for ‘Ongoing Revolutionary Process’, a period of revolutionary activity between 1974 and 1975, marked Portugal’s democratic formation and paved the way for the formulation of urban and housing rights. In November 1975, a second coup took place in opposition to the more radical factions, ending the participatory democracy experiment and leading to the construction of a liberal and representative democratic model (Nunes & Serra, 2004).

This paper aims to provide a historical overview of public housing occupations in Portugal during the PREC era, paying particular attention to the neighbourhood known today as ‘Bairro 2 de Maio’ in Ajuda, the western part of Lisbon. We will seek answers to two main questions: firstly, what triggered the occupations that started only two days after the coup, and secondly, how did the occupiers manage to defend and legalise their occupations? In so doing, we will seek to contribute to the literature that analyses first-hand information on the PREC-era occupations (Downs, 1980, 1989; Ferreira, 1986; Queirós & Pereira, 2018; Vilaça, 1991, 1994). In particular, while acknowledging the importance of precarious housing conditions to creating the impetus for the mobilisation of poorly-housed urban dwellers (Arthuys & Gros, 1976; Bandeirinha et al., 2018; Cerezales, 2003; Lima dos Santos et al., 1975), we wish to broaden existing knowledge on the analysis of the factors that triggered and made possible the mobilisation of urban residents in such a short period of time (Baía, 2017; Downs, 1980; Ferreira, 1986; Pinto, 2015; Queirós & Pereira, 2018).

As the research project developed by Pestana Lages and Dias Pereira focused on collecting accounts of occupations by those involved during the PREC period, we would like to contribute towards building further knowledge on this very singular period in Portuguese history. We aim to identify characteristics of both the PREC occupation movement and the political and societal context that triggered the occupations, as well as to explore how the occupiers managed to defend and legalise the occupations, sustaining them over the years.

2. ‘Ongoing Revolutionary Process’ or PREC: Years of Radical Change in Portugal

After WWII, Portugal experienced large-scale urbanisation, closely indebted to a late process of industrialisation, with rural-to-urban migration increasing from the 1960s onwards (P. Costa, 1993). Raúl da Silva Pereira estimated that the housing shortage in Portugal ‘was [in 1963] in the order of 460,000, of which 150,000 were very urgent’ based on 1950 data (1963, p. 225). From the military dictatorship (1926-1932) to the Salazar and Caetano dictatorships (1933-1974), public housing did not account for a significant percentage, proven by the low 10.8% of housing built between 1953 and 1973 (Gros, 1994, p. 93). However, it was not only about numbers but even more the living conditions: Bandeirinha pointed out that a striking 25 per cent of the Portuguese population lived without safety or health conditions, comfort or privacy, cheek by jowl in barracas [shacks] or places of a minimal living standard (2011, p.68). Less than half (47%) had access to a running water supply and only a third (30%) to the sewage network (Bandeirinha et al., 2018, p.241).

Access to housing was a central demand of the occupation movement, which was part of the intense mass mobilisation, grassroots and participatory democracy experiments that surged during the PREC era (Nunes & Serra, 2004). Housing conditions were a central concern of the newly-formed urban movements, which demanded better housing conditions in precarious, self-built neighbourhoods and in rental housing (Bandeirinha et al., 2018). Occupations targeted both urban and rural properties and, in many cases, involved negotiation with previous owners of the buildings (private, state or municipal) over the legalisation of the occupations (Bandeirinha et al., 2018; Ferreira, 1986; Pinto, 2015). Less than two days after the coup, the people of the Boavista neighbourhood began occupying empty council houses, and a few days later, occupations followed in an under-construction housing estate in Ajuda (Pinto, 2015). In Lisbon, Setúbal, and Porto, occupations began by targeting vacant government-owned or council housing that was new or still under construction, also because of the infrequent, and laborious selection process (Downs, 1980; Pinto, 2015; Queirós & Pereira, 2018). Between April 26 and May 9 1974, approximately 2,000 social housing dwellings in Lisbon, Setúbal, Porto and Madeira were occupied (Bandeirinha, 2011, p.113). The occupations also involved companies and factories (Lima dos Santos et al., 1975). From February 1975 onwards, occupations began targeting private housing and, in addition, many occupations set about providing spaces for collective use, such as day-care centres, clinics and party headquarters (Downs, 1980, p.279). The implementation of SAAL (Serviço de Apoio Ambulatório Local, Mobile Service for Local Support) was also fundamental in the fight for better housing during the time of PREC. SAAL was a state-assisted programme dedicated to improving and building new self-built housing in run-down neighbourhoods, with resident committees working together with architects and other specialists (Bandeirinha, 2011; A. A. Costa et al., 2019; Portas, 1986; R. Santos, 2016; R. Santos & Drago, 2024). The primary housing policies being implemented during the PREC era and in subsequent years were SAAL and CAR (Comissão para o Alojamento dos Refugiados, Commission for Refugee Accommodation), dedicated to providing housing for those Portuguese who were returning from the ex-colonies after independence. They had very different approaches: SAAL focused on innovative design processes and political deliberation through the idea of ‘participation,’ while CAR’s programme favoured innovative construction techniques and experimentation with prefabrication to foster new relationships between the central government, construction industry, and local authorities (Bandeirinha et al., 2018). Housing movements also were invested in the struggle to limit speculative rents and against repressive council housing management practices (Downs, 1980).

This period also saw housing-occupation movements in other parts of Europe. In the 1970s, a major squatting campaign took place in the Paris metropolitan area driven by Maoist-inspired Comités de quartier du Secours rouge activists, intimately associated with the birth of a larger urban struggle. However, these occupations received little external support and were framed by the authorities as ‘dangerously leftist’, which led to the eviction of the occupying families (Aguilera & Bouillon, 2013). In London, occupier movements developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s, consisting of moving people to the considerable stock of abandoned buildings. As in Paris, they faced a violent response when the city council sued them in court, hired thugs to attack the occupiers, cut off power from the buildings and pursued violent evictions (Milligan, 2016).

3. Theorising PREC

Literature on social, urban and housing movements has extensively investigated the motivations behind people’s involvement in collective action and the factors contributing to social movements’ emergence. While not aiming to provide an exhaustive list, our study acknowledges various explanations. Structural strain theory asserts that individuals engage in collective action as a response to grievances they face (Smelser, 1962). Resource mobilisation theory likewise saw mobilisation as a rational response to unsatisfactory conditions but focused more on the capacity to mobilise resources, arguing that that was key to the emergence of collective action (McCarthy & Zald, 1977). From another angle, the political process approach highlights political opportunities, arguing that favourable conditions are necessary for a movement to achieve its objectives (Tilly, 1978).

Manuel Castells’ social movement framework, adopted by many authors who have analysed the PREC era, emphasised the link of the emerging social movements in the 1960s and 1970s to overarching changes in the structure and functioning of advanced industrial societies. For Castells, an ‘urban social movement’ (USM) can ‘influence structural social change and transform the urban meanings’ (Castells, 1983, p.183). He sought to theorise on the requirements needed for the movements to achieve this transformation and maintained they should articulate their goals along three axes: to attain a city organised around its use value / collective consumption (including housing, education and health), to create a specific community culture; and to demand self-management and power for the local government level (Castells, 1983, pp.319-320.) Furthermore, they should be able to build relationships with other actors, such as the media, the ‘professional classes’ and the political parties, while still maintaining their independence from party politics. In addition, they should be conscious of their role as an urban social movement (Castells, 1983, p.322).

In his analysis of occupation movements during the PREC era, Charles Downs (1980, 1989) builds his theoretical framework largely upon Castells’s urban social movement theory. His 1989 book conceptualises PREC occupation movements as an element of class struggle and a ‘normal response of populations in times of popular advance and favourable conjuncture’ (Downs, 1989, p.10). Echoing Castells, he argues that changes in the conjuncture directly affect movements to the extent they embody class positions represented in the general relation of forces, and when a broad class offensive develops, USM in those class fractions are likely to unite. In his study of the PREC housing occupation movement in Lisbon, Vítor Matias Ferreira (1986) also emphasised the social base of the struggle, suggesting that the movement had managed to transcend its ‘lumpenproletariat and shantytown dweller’ origins to draw in sections of the working class and urban petty bourgeoisie. He argued, using Alan Touraine’s (1985) terminology, that by doing so, the movement transformed itself from a limited ‘claim-making movement’ making general demands for decent housing into a ‘protest movement’, which identified the state and municipality as the targets of its political action. Yet the diversity of social origins also hindered the building of a city-wide movement. For Downs, nonetheless, the defining element of the PREC movement was the changes in the political conjuncture: according to Downs, that was the essential factor contributing to the development of internal dynamics, the building of the social base, and progress in terms of formulation of strategies and achieving political significance (Downs, 1989, p.10).

Pedro Ramos Pinto’s (2015) analysis of the PREC occupation movement departs from another angle. Pinto bases his examination on the ‘contentious politics’ approach (McAdam et al., 2001) that underscores political opportunities and constraints but also considers the political and institutional context in which the social movements occur, aiming for a more dynamic and relational account of contestation. Central to the contentious politics approach is also the focus on making collective action frames, which create shared ideas to validate their actions. In addition, borrowing from the ‘mobilising structures’ concept, Diani and McAdam (2003) emphasise the role of groups and social networks in constructing collective action. Pinto focuses on all these aspects but emphasises in particular the previous creation of collective action frames concerning the rights residents should have access to, the preceding building of a common identity and ideas of urban citizenship, and the role of previously-created mobilising structures (Pinto, 2015, p. 12).

Nevertheless, the contentious politics approach does not focus enough on the protest’s cultural context and structural origins (della Porta & Diani, 2006). These, in turn, are under significant scrutiny in Bourdieu (1984, 1999) and Wacquant’s (2008, 2016) work on symbolic division and social space. Queirós and Pereira (2018) draw from this work to establish an analysis of how social agents developed practical and symbolic competencies to resist territorial stigma and exclusion in the historical centre of Porto during the PREC era. These processes necessarily occur in a specific spatial-temporal reality, which had aspects that made producing collective forms of action possible. They conclude that the production of these competencies occurs at the intersection of social agents’ strategies and mechanisms of social reproduction (Queirós & Pereira, 2018, p. 858).

To date, the research on occupation movements in Europe tends to have focused on left-libertarian, anarchist movements that have an intensely politicised discourse (Aguilera & Bouillon, 2013; Esposito & Chiodelli, 2023). However, recent investigations have also turned their gaze on movements where the providing of housing is a central demand. Hence, occupations have been seen as recuperating housing from banks through challenging regimes of property ownership (García-Lamarca, 2017; Gonick, 2016) as well as through an assessment of the socio-political outcomes of housing and occupation movements (Martínez, 2019). They also tend to highlight the contribution of occupiers’ movements to the making of the city: its policies, services, housing provision and construction, as well as the urban governance processes (Martínez, 2020). Of particular interest to our work is Grazioli’s and Caciagli’s (2018) analysis that identifies housing occupations as ‘urban commons’, contributing to a renewed ‘right to the city’, emphasising the right to participate in the making of urban life (Lefebvre, 1968). We are interested in looking at the contribution of occupations as ‘commoning initiatives’ as defined by Caffentzis and Federici: as an ‘embryonic form of alternative production’ against the capitalist and neoliberal market logic (Caffentzis & Federici, 2014).

In this paper, we draw from these various theoretical insights to explore the elements that fostered the emergence of occupations in post-revolutionary Portugal, as well as those that contribute to their longevity and regularisation. We put forward that on one hand, decisive factors were the existing panorama of housing precarity, the opportunity to set political change in motion, and the previous networks that functioned as mobilising structures for collective action frameworks. On the other, we argue that the ability to prolong occupations was intimately linked to the specifics of the historical and political moment, the favourable attitude of the state and the sympathies of the public in general, as well as phenomena of collective mobilisation and the relationships of solidarity built among the resident committees.

4. Methodology

The main methodological orientation for this paper comes from notions of ‘rebel archives’ and ‘radical memory work,’ founded on the idea that ‘remembering and honouring the past, as well as the present, is critical in building power for a more just future’ (Dalloul et al., 2020, p.34). The methodology was anchored in the idea of community-generated research, with specific focus on the memories of the community, and recording their histories. Remembering and registering community history creates potential to support emancipatory action (Bogado, 2019). The paper is the direct outcome of a 12-month research project named Abrir Abril1

(‘To open April’, to translate a phonetic pun into English, henceforth AA). From October 2022 to October 2023, AA was dedicated to celebrating the 50th anniversary in 2024 of democracy in Portugal by highlighting its achievements regarding the right to housing and freedom by association. The project aimed to motivate communities in three neighbourhoods in Lisbon by creating living history labs (a citizen science project), organising forums and tours, and mapping local associations. AA created a ‘living history laboratory’ in each of the three neighbourhoods. Between September 2022 and October 2023, our team collected data and built a repository of memories related to the history of places and people, with a particular focus on the achievements of democracy, through a compilation of documentary footage and filmed life stories, in a total of 46 interviews. This article focuses solely on the work carried out in the Bairro 2 de Maio neighbourhood. After exploratory conversations with the local associations, individuals from their ranks or living in the area were identified to make up a team of seven local urban researchers. They were trained over three sessions by both NOVA and ISCTE’s research centres in sessions that included both theoretical and practical demonstrations. Learning how to conduct life story interviews demanded preparation, so the interview guide was co-designed and tested. One of this paper’s authors, Miguel Tomé acted as a ‘local researcher’ at 2 de Maio, responsible for interviewing 16 persons directly involved in the neighbourhood occupation and collecting data. A proud ‘child of 2 de Maio’, his involvement in this project owes much also to his own particular circumstances as he is the grandson of Ausenda Moreira, one of the occupation’s leaders. He is also dedicated to collecting and building an archive on the radical history of Bairro 2 de Maio.

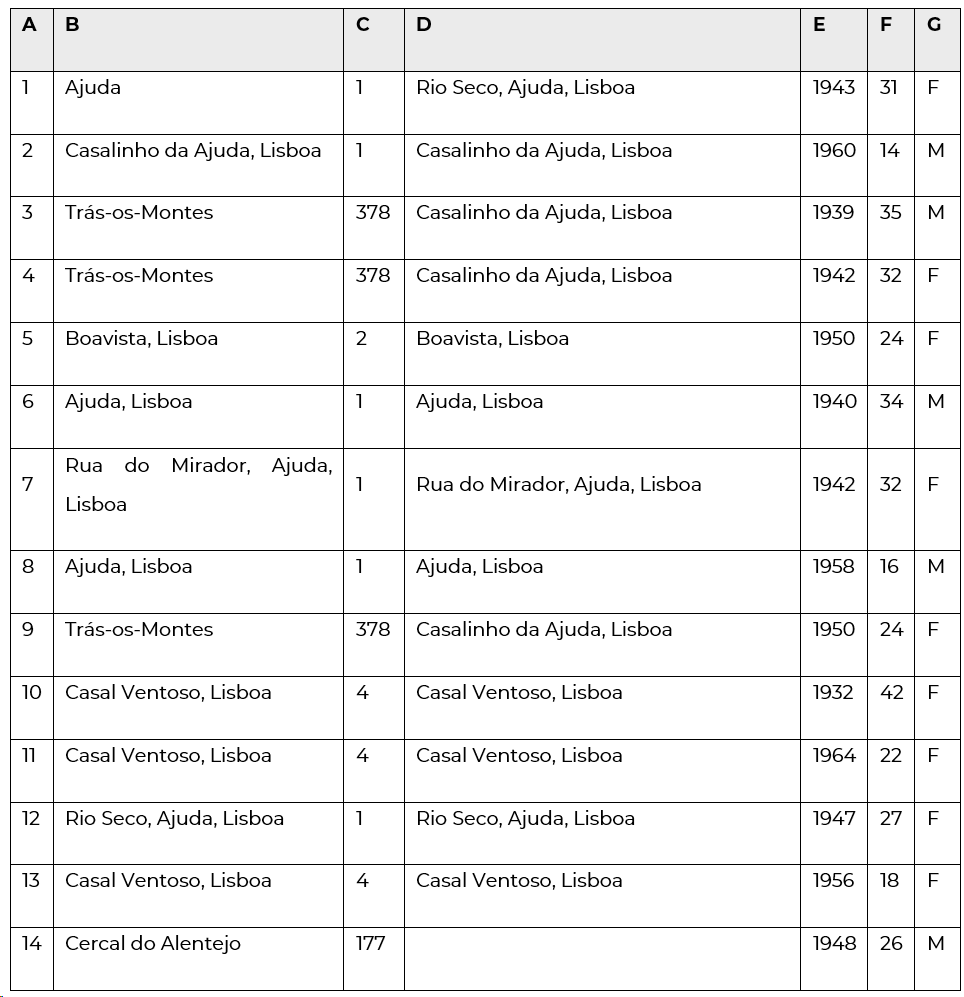

Table 1 gives an overview of the interviewees, considering aspects relevant to this issue, such as the place of birth, age at occupation and migration path. We can also add that all the interviewees are married and still live in Bairro 2 de Maio. All interviewees participated in the occupation except for interviewee 16, who was born in the same year as the Carnation Revolution. Interviewee 16 was included due to her role as a leader of a non-governmental organisation created in the last decade, with strong community ties working in the neighbourhood. As a counterpart to the interviews made in the course of the Abrir Abril project, we also included one interview conducted by Saaristo in 2020 with one of the founders of the women right’s organisation UMAR, who was also an active participant in PREC occupations and other mobilisations (INT 17).

5. Occupying 2 de Maio

Just before the Carnation Revolution, the Salazar Foundation was building a neighbourhood for employees of the International and State Defence Police, known as PIDE2, reinforcing the fact that housing stock during the dictatorship was mainly intended for state officials or specific social groups. The Salazar Foundation, a ‘private institution of general public utility’, set up on July 31 1969, had the mission of ‘providing housing in good economic, hygienic, and moral conditions for those who, due to their limited resources, cannot obtain it by any other means’ (article 2 of Decree-Law 721/73). Twenty-five of the buildings under construction and 270 dwellings were occupied by force on May 2, 1974, renamed later in honour of the date of the occupation. Today, the neighbourhood sits close to the Monsanto Forest Park and the University Campus of the University of Lisbon, enjoying good views over the river Tagus, yet still relatively isolated from the urban fabric. More units were later built and in 1996, the neighbourhood started to be managed by the Lisbon City Council as a council estate. According to the statistics of GEBALIS, a municipally-owned company that manages Lisbon’s public housing, running 2 de Maio since 2003, there are now 64 buildings, where around 1700 people live, in 616 housing units (see Figure 1).3

5.1 Why occupy? Housing precarity and overcrowding

The interviews at Bairro 2 de Maio confirm the previously-mentioned pattern of urbanisation and its implications for the housing shortage and living conditions. Most interviewees have a history of rural flight (their own or their parents), having come to Lisbon in the 1930s, 1940s or 1950s in search of better living conditions. In 1970, the census registered around 19,000 families of the municipality of Lisbon living in housing that was considered ‘non-classic’, such as barracas (wooden shacks), mobile homes, hostels and other ‘ill-defined dwellings’ (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 1970). The survey conducted by the housing office of Lisbon City Council (Gabinete Técnico da Habitação, GTH) established even higher figures of close to 22,000 families, representing around 9% of the population of the municipality at the time, leading to the establishment of a plan for the ‘eradication of barracas’ (Antunes, 2017, pp.205, 226). Before the Revolution, the regime had given little thought to housing policies, conceived first as a tool to benefit certain population groups (Bandeirinha et al., 2018). When housing policies started to have a more developmentalist approach, during the regime of Caetano (1968-74), public funds were sapped by the colonial wars (Lima dos Santos et al., 1975). While often occupying a geographically central location in the cities, the residents of shacks and other ‘non-classic’ dwellings were socio-culturally excluded from the surrounding city, facing territorial stigmatisation (Ferreira, 1986; Queirós & Pereira, 2018). As our interviewees, describing their housing conditions, show:

At the time [1974], I already had four children and lived with my in-laws. I had one room in the attic. It was already complicated because I had four children. My two daughters slept with me and my husband in the same bed. And then there was the eldest, who slept on the floor behind the door, and the youngest, who was 15 days old, sleeping in a carrycot. When I needed to go out of the room, I had to wake up my son so I could get past. (INT 12)

I needed a house because we lived in a shack with no conditions whatsoever. When it rained, the rain came in through the roof and went out through the door. (INT 11)

Artur João Goulart © Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa - AJG002364

Figure 2 Casal Ventoso (1961), a degraded area 4km away from 2 de Maio, where three of our interviewees and their families lived before the occupation

If the new urban poor were living in inadequate housing conditions, people returning from the former colonies (INT 3 and INT 14) also had difficulty finding housing. They belonged to the so-called retornados, the ‘returnees’, Portuguese settlers in the former colonies who returned to Portugal following independence. As a result of decolonisation, it is estimated that between 500,000 and 800,000 Portuguese settlers left their homes in Africa between 1974 and 1979, mainly coming to Portugal (Peralta, 2021). Even if INT 3 and INT 4 immigrants had arrived before, their description of what they found on arrival is like all those ‘returning’: a poor country, where the illiteracy rate was 35 per cent, economically depressed, with high child mortality, and where finding a place to live in was an issue (Arthuys & Gros, 1976). Both interviewees lived with their families in overcrowded conditions before joining the occupation movement (see Figure 2).

5.2 How to occupy somewhere still under construction? Occupiers and allies

For me, one of the most beautiful sights at that time was the occupation of Bairro 2 de Maio. It was a mass of people from the shantytowns who went up the Calçada da Ajuda towards the neighbourhood of the Oliveira Salazar Foundation, where there were a number of unfinished and unoccupied buildings. Seeing the crowd converge on the neighbourhood was unforgettable; five minutes later, all the windows were flung open. Everyone at their window were shouting: ‘I already have a house! I’ve got a house!’ Jorge Falcato Simões, architect, cited in Rodrigues (1994).

In Lisbon, notable instances of proletariat occupation after April 25 included those that took place in Bairro Camarário de Monsanto and Bairro da Boavista on April 29 and Bairro Valfundão, Marvila on April 30 (Bandeirinha, 2011). On May 2, residents of Casalinho da Ajuda occupied the Bairro da Fundação Salazar, renaming it Bairro 2 de Maio.

The interviewees recount that they heard about the occupation movement mainly from the radio, meaning that it is still unknown who set it off. They all mention the euphoria of walking up Ajuda, abandoning their jobs and errands they were running. The revolution limited state retaliation in an unforeseen way due to the level of general disorder, and after the success of the first occupations, people were encouraged to press on: a ‘revolutionary legitimacy’ reigned (Queirós & Pereira, 2018, p.867). In an atmosphere of extreme housing precarity, corrupt council housing management, and the MFA’s call to reform the regular police force, people took advantage of the police force’s lack of organisation (Downs, 1980, pp.278-279) to mobilise. However, Queirós and Pereira (2018, p. 867) argue that at least in Porto, such a degree of mobilisation cannot be explained simply by circumstantial factors: it had strong historical roots, building on a general sentiment of exclusion and stigmatisation, as well as on a groundswell of previous locally-constituted political activity and local leadership. In 2 de Maio, after occupiers had managed to get into the apartments that were still under construction, there they stayed, family members taking turns to be present and thus avoid losing their newly-acquired homes to others.

I was working in the livestock breeding trade at the Campo de Ourique market, and then I heard on the radio that there was an occupation happening. I dropped everything and came up there straight away to occupy a house for myself as well. (INT 10)

My husband was working, and I had four children with me, the youngest being 15 days old. I took my children and went to stay up there. (…) I have only had time to occupy this [flat] of mine, where I have been for 49 years and never left. [During the occupation] we could not even leave here because we’d automatically end up homeless if I left. (INT 12)

A colleague of mine told me that people were occupying properties, and she was coming here, and I came with her. I found the streets full of people, each grabbing a house for themselves, a house to live in! (INT 9)

The fact that 2 de Maio was still under construction did not deter occupiers. Described by all as a ‘skeleton,’ with ‘no floor, no walls, no windows, nothing’ (INT 14), no power and no running water, this made the occupation of 2 de Maio a challenge. INT 1 was sick with cholera, an outbreak that ravaged the poorest neighbourhoods and also descended upon the 2 de Maio neighbourhood. Meals were prepared on a camping cooker, and the nearby fields were used in the absence of toilets. A recurring comment is arriving home with muddy shoes, as there were no roads. Yet the dedication to the occupation cause was strong:

There was such a bond between all the people here. The people were so united, I never saw anything like that again. There were houses with building materials, and we broke in and started stealing materials to start building our houses. That’s the truth. We, the people, were really united to fight. (INT 1)

This wave of occupations extended to Lisbon’s industrial belt, prompting the Lisbon Tenants’ Association to call for a rent freeze. By May 5, around 1000 residents occupied 23 blocks in Chelas. Demonstrations of support for the National Salvation Junta occurred in Belém on May 8, accompanied by more occupations in Bairro Marcello Caetano (now Bairro Humberto Delgado). Roque Laia, president of the Lisbon Tenants’ Association, justified these occupations by highlighting the indecency of houses lying vacant amidst widespread homelessness. Additional occupations were reported in Chelas and Madorna on May 10, involving properties intended for municipal and social service employees (Bandeirinha, 2011). The occupation movement quickly rephrased their claims as being an ‘appropriation of what belongs to them’, as a means to legitimate their demands (Ferreira, 1986, p.557).

5.3. Organisation and unity to defend occupations: a broader struggle

The neighbourhoods that were pioneers in the occupation movement had previously been the focus of the dictatorship’s urban policies and interventions. This had contributed both to the creation of expectations from part of the population - they were already anticipating they might be resettled - as well as to the access to municipal authorities and the formation of networks with other key protagonists, such as social workers, the clergy, students, and left-wing political activists (2015). From the beginning, the occupiers were not alone; the poor residents of 2 de Maio were supported by school-goers, namely pupils from Liceu Camões, a secondary school with solid political engagement against the dictatorship. INT 1, who became one of the leaders of this occupation, mentioned that she went with students to Rio Seco (a nearby deprived area) to call people to occupy on the first day. Thus, external allies got behind the occupation, inciting the population to claim their right to housing. Previous alliances had as a result already been formed, which probably helped spur the occupations on and create conditions for them to happen. In fact, Ferreira (1986) sees these movements as bringing together various social classes, even if he believes it was the socially segregated and isolated urban poor set off the movement. A community leader interviewed in the study said, ‘The students and the people from the UPD never abandoned us.’ She describes how the UDP (Popular Democratic Party), a Maoist radical left-wing party, supported those in the neighbourhood who were instrumental in the occupation. The Maoist MRPP (Movement for the Reorganisation of the Portuguese Proletariat) and other organisations also seem to have played a vital role in supporting occupations (Pinto, 2015). However, it is important we frame these alliances not in paternalistic terms, as residents frequently rejected any attempt to tell them what to do (Queirós & Pereira, 2018). Our interviewees (INT 10, 13) do bring up the involvement of the student population. Contacts with other neighbourhoods, specifically Casalinho, Camarão da Ajuda, and Padre Cruz, were also mentioned as a means to form a common front based on mutual aid.

After the occupation, the residents began to organise neighbourhood meetings, in which they discussed, elected representatives, and formed a resident committee (comissão de moradores, CM):

We’ve occupied the houses. Now, we must put the occupation in order and see what can be done. It’s the neediest who require the most help. We must help each other and work towards unity. We’ll put together a list of those who will be offered the finished houses, and once we’ve approved it, it must be put into practice, whatever happens. The people must take matters into their own hands. Regarding the unfinished houses, we should also occupy them and demand that the contractor finishes the job. He’s already been paid, so he must get the work done. Until then, nobody will pay rent! The houses belong to the people! The people will win! Onwards with the fight to put food on the table!’ Statement by the occupiers of 2 de Maio (cited in Rodrigues, 1994, pp. 21-22).4

Building solidarity and collective strategies to provide a framework for the action was a central part of the movement: committees and residents alike supported each other.

Sometimes, a neighbour would make some food and then share it with us: ‘There you go.’ Or, I would do it and give it to the neighbours. We were united, and we couldn’t even leave the premises. There always had to be someone or other around in the building, to ensure no one took the house away from us. (INT12)

Downs (1980) interprets the formation of resident committees as part of the broader class struggle taking place within Portuguese society, which was spurred on by the changes in the political status quo. However, other participants (Baía, 2017; Queirós & Pereira, 2018) emphasise rather the accumulation of a diverse range of factors: the political climate was important, but equally so were previous experiences in local organisation and proletarian struggle, alliances with students’ and workers’ movements, and segregation that had led to shared everyday experiences. The resident committees organised themselves in a variety of ways and acted as alternative power structures to the city councils: as the city councils were adapting themselves to the demands of the revolutionary period, resident committees ended up playing their own role, in many cases, managing at a local level, liaising directly with the central state and the MFA (Varela & Alcântara, 2016). They gradually become consolidated as autonomous organisations, and then establish alliances with well-positioned actors to support them (Cerezales, 2003).

In addition to the revolutionary parties, military organisations also played an essential role, such as COPCON (Comando Operacional do Continente, the Continental Operational Command), a military coordination unit created by the MFA in 1974, headed by Otelo S. de Carvalho. COPCON was also able to provide the occupiers with back-up in what were sometimes violent encounters (Cerezales, 2003). The MFA’s Cultural Development Campaign was particularly instrumental in incentivising local self-organisation (Downs, 1980). One interview describes clashes between the occupiers and those who were trying to scare them into leaving the houses they occupied. Residents’ committees were essential to the planning of shifts to defend the occupied properties. Other interviewees mention the COPCON and its leader, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho:

The one time, we were scared stiff. There were [COPCON] soldiers at the front door, and they were all lined up around the building. So many people. The police cars. We were terrified. (INT 15)

Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho never left. He was the one who told the soldiers what to do. We didn’t leave [2 de Maio] because the soldiers also took care of us. (…) I had many meetings with Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho at the Military Police Station. A lot! (INT 1)

The number of active commissions in Lisbon increased steadily throughout the revolutionary period. In January 1975, the first meeting was held in Lisbon of what would become the Intercommission of Lisbon’s Residents (Intercomissão de Moradores de Lisboa). This commission jointly planned strategies for the housing campaign and sought ‘popular control’ for all the vacant apartments (J. H. Santos, 2014), which included 18 resident committees. Other coordinating bodies included the Central Commission of Resident Committees of the Municipal Neighbourhoods of Porto, created on December 13 1974, and the Intercommission of the Barracas Neighbourhoods in Setúbal, in February 1975 (Varela & Alcântara, 2016). The organised resident committees compiled lists of demands to be presented to the authorities; for example, the committees set up in the Boavista, Amendoeiras and 2 de Maio neighbourhoods went to the provisional headquarters of the Junta de Salvação Nacional (National Salvation Junta) to demand the completion of houses and their legal allocation (Antunes, 2017, p.243).

The period from November 1974 to March 1975 involved the founding of many resident committees in informal neighbourhood shantytowns (in case they did not already exist beforehand) as well as occupiers’ committees that opposed resident committees which had collaborated with parish councils - typically critical of the occupations - advocating for the principle of ‘self-determination at all levels of government’ (Downs, 1980, p.273).

There were changes in the social make-up of the movements, which now incorporated the working class from outside the shantytowns and some parts of the urban bourgeoisie (Ferreira, 1986). According to Ferreira (1986), this phase also saw a change in terms of framing of the movement’s demands, moving on from the recognition of its claims to a form of political-institutional protest, as espoused by Alan Touraine’s (1985). However, Ferreira points out that the movement did not condemn private property ownership as such but rather insisted on the ‘socialisation of collective appropriation, demanding that the State restructure and regularise property interrelations (Ferreira, 1986, pp.564-565). In Lisbon, after the establishment of inter-resident committees, intensive discussions led to a common list of demands presented to the government on February 15, 1975. This document prominently rejected the idea to self-build, which was initially a key part of the SAAL programme and supported by Portas. Residents viewed self-building as another kind of exploitation, exacerbating the primary exploitation of their labour (Bandeirinha et al., 2018).

A second wave of occupations began on the night of February 18, 1975, when the 120-day time limit, set by decree-law 445/74, for property owners to rent out vacant properties ran out, this time intended for private housing. Ironically this law, intended to protect private property, created conditions that further legitimised these occupations. An estimated 2,500 apartments in Lisbon were occupied in the following days. Unlike the first wave, these occupations were better organised, as participants had an example to follow and knew when the legal waiting period would expire. Committees were formed to manage the occupations, and meetings were held to allocate housing based on need and the willingness to take risks. Additionally, many buildings were occupied for collective purposes, such as day-care centres, clinics, and party headquarters (Downs, 1980). By March 1975, there were 57 CMs in Lisbon, mobilising thousands of residents, and new commissions appeared regularly from March onwards up to November 1975 (Pinto, 2015; Varela & Alcântara, 2016).

In September and October 1975, various resident committees declared their intention to occupy all vacant housing to prevent opportunistic takeovers and allocate it to those in need. Although not fully implemented, the occupation of new private apartments began, marking a less intense but more organised third wave. Driven by revolutionary groups and returning refugees, this phase primarily involved individuals needing housing rather than shantytown residents, hoping they could eventually pay rent based on their income (Downs, 1980).

5.4 State attitude towards occupations: ambivalent or contradictory?

How occupations were framed in the mainstream public debate had a significant impact on the occupiers’ chances to make their claims heard. Such approaches also had a potential impact on the State’s own attitude towards the occupations. The occupations have been described as one of the most extraordinary moments of the Revolution: both the fact that so many people adopted such a transgressive strategy to claim the right to housing and that the state did not repress them, only goes to illustrate how much changed in the space of just a few days after the coup (Pinto, 2015, p.95). The revolutionary spirit of the time contributed significantly to the public acceptance of occupations:

So, at that time, the political and social climate was very favourable towards these mobilisations. There was a movement, in which I took part, of demonstrations whose principal slogan was ‘Casas sim, barracas não!’ (‘Yes to homes, no to slum housing!’). So, there was this whole movement of occupations that was well-received by society, right? Society wasn’t mistaken when it thought that people shouldn’t live in shacks and that they had the right to a home of one’s own. (INT 17)

Throughout the entire PREC period, the occupation movement navigated the fine line between illegality-operating at the edges of the law but consistently beyond it-and legitimacy, which each movement relentlessly sought to achieve, both politically and especially socio-culturally. The interplay between ‘illegality versus legitimacy’ set the framework for the dialectic in which these social movements emerged and faced off with each another (Ferreira, 1986, pp. 568-5689). According to Downs (1980, p.281), the issue of the legalisation and legitimacy of the occupations often highlighted two broad political lines and groupings: those being, despite differing ideologies, either in support of the potential for social change driven by popular movements; and those - with varying class interests - who opposed the progress of the popular movement.

After the coup, the MFA appointed the Junta de Salvação Nacional to govern until the establishment of the first Provisional Government. According to Pinto (2015), the Junta decided to wait for its appointment and thus did not interfere with the ongoing occupation efforts. The Junta also attempted to establish a mid-term solution by aiming to create regulations for occupations, such as the paying of rents (Bandeirinha, 2011). Conversely, the police force, which was labelled as fascist by the population, had lost its authority and capacity to act. At the same time, the military was hesitant to take measures against the population as the coup had been undertaken in the name of the people and their rights. The newspaper A Capital also published a statement by a Military Police officer who, at the moment of occupation of the 2 de Maio neighbourhood insisted that he was only there to keep an eye on things: ‘The occupation of the houses took place serenely, which led the M[ilitary] P[olice] unit to withdraw, much to the joy of shantytown residents’ (A Capital, May 3 1974, p. 32., cited in Pinto, 2015, p.105).

However, on May 14 1974, on the eve of the transfer of power to the First Provisional Government, the Junta decided to take a stance in favour of the housing occupations, provided that specific requirements were met, namely the payment of rents to landlords (public and private) and the vacating of buildings under construction so that they could be finished, which led to yet more occupations (Antunes, 2017, p. 243-5). Despite targeting government housing, private property owners felt vulnerable, prompting the government to issue decree-law 445/74 on September 12 (Downs, 1989). In 120 days, landlords were required to declare and rent ‘habitable” vacant housing to the City Council and the population was urged to safeguard its implementation by the Lisbon City Council as well as the Communist Party (Downs, 1980; Pinto, 2015). This did not, however, pacify urban residents who were frustrated with their housing conditions, and occupations continued from November 1974 onwards (Santos, 2014). After the second major wave of occupations from February 1975 onwards, the police stepped in, prompting increased mobilisation among the occupants. Although some evictions occurred, the occupations persisted, albeit at a slower pace. They intensified again after the attempted right-wing military coup on March 11, 1975, and continued into April (Downs, 1980, p. 279).

In April 1975, a new provisional government enacted Decree-Law No. 198-A/75 on ‘Legalisation of occupations,’ which sought to consolidate its approach to occupations, yet faced challenges after trying to please all involved (Bandeirinha, 2011).

There are hundreds of thousands of families in the country without housing or living in sub-standard conditions. And it is clear that, despite the measures already taken or under scrutiny and the actions planned to encourage construction, it will not be possible, even in the medium term, to completely solve the severe problem of adequately housing these families through new construction. The way to alleviate this shortage in the short term, which the most basic principles of social justice demand, is to make full use of the country’s housing stock since as long as there are people without homes, it is unacceptable that there should be homes without people. Decree-Law 198-A/75, April 14 1975, our emphasis.

The Decree-Law stated that it would seek the legalisation of occupations made ‘to satisfy the urgent needs of extremely disadvantaged people’ but, conversely, also maintained that it would be ‘necessary to prevent, in a definitive and very firm way’ all further occupations (Decree-Law no. 198-A/75). One of the particularities was the article on ‘compulsory rental contracts,’ meaning that if the landlord did not contact the occupiers, the local authority could sign the contract and receive part of the rent. Although the law was mostly in favour of the vast majority of the occupations, it still did not meet the expectations of some of the resident committees, resulting in protests demanding an ‘end to evictions for the right to housing!’, the ‘immediate legalisation of occupied houses!’ and the repeal of Decree-Law 198-A/75 (Antunes, 2017, p.245).

5.5 Regularisation of occupations: towards a right to housing?

After the ‘hot summer’ of 1975, a turbulent period characterised by clashes between rightist and leftist groups and fissures among those on the left, the Sixth Provisional Government began its mandate in September 1975. In this period, more centrist and ‘moderate’ forces of the MFA, the PS (Partido Socialista, the Socialist Party) and the PPD (Partido Popular Democrático, Democratic People’s Party) took power. These two parties imposed as conditions of their participation in government, among other things, the eviction of those occupying properties and the dismantling of ‘popular power’ structures (Cerezales, 2003, p.101). In November 1975, COPCON led a coup that was quickly defeated and resulted in the abolition of COPCON. This moment marks the beginning of the decline of leftist forces in Portugal: when the coalition government of conservative and moderate wings of the military and the political centre took control of the political process in November 1975, and the revolutionary spirit began to dissipate, further weakened by the approval of the new Constitution in April 1976 (Nunes & Serra, 2004). Despite mass disbanding of resident committees after November 25, they did not disappear entirely; while some dissolved shortly after, others remained active (Pinto, 2015). According to Downs (1980), the most resilient were those from self-built neighbourhoods aligned with SAAL and those engaged in mobilising at a local level and involved in tangible projects like day-care centres, which sometimes became their sole focus.

After the inauguration of the first constitutional government of Mário Soares in July 1976, the government adopted a strategy of inflexibility and repression towards the occupations. Housing policies began to be adopt neoliberalist thinking, channelling the state housing budget mainly into the financing of subsidised interest paid to banks by the state for home purchases and into loan mechanisms for public and non-profit entities to boost the market and the construction sector as well as lessen the state’s responsibility in the providing of housing5 (Bandeirinha et al., 2018).

This move to disband on the part of the authorities drastically altered the prospects for yet more change, impacting occupiers’ perceptions. In 1975, there was a collective assertion that the housing problem was a social issue requiring a unified struggle. People pledged not to leave their shacks until everyone in the neighbourhood could move together-a feasible objective through collective action. By 1976, the same individuals were seeking alternative solutions to the housing problem, acknowledging the need to do so due to changing circumstances, marking a shift in the approach to housing activism (Downs, 1980). Through her investigation of the remaining resident committees - now transformed into neighbourhood associations - in Porto in the late 1980s, Vilaça (1991) argues that there has been a fundamental reshaping of the demands and the roles of these associations. From that moment on, associations championed the adoption of multiple strategies, including liaising with politicians from a variety of backgrounds, advocating for the cleaning up and better running of neighbourhoods, and the right to privacy (Vilaça, 1991, p.183).

Decree-Law 294/77 of July 20 came into force and repealed the 1975 law that had legalised occupations but was concerned exclusively with the occupation of private dwellings. In the quest for solutions for the occupation of public housing, the public authorities opted to seek a dialogue with resident committees, which generally agreed to the demands and rent proposals suggested (Antunes, 2017). The fact that the dialogues were engaged in collectively by the resident committees was essential to their having sufficient negotiating power to face the state, as argued by one of the interviewees:

As for these occupations, I think there also has to be someone who is on the side of the people, even nowadays, right? And this person has to have the strength to negotiate because the people don’t, not all the time. So, I think this is one of the lessons that can also be learned from that period: (…) They did what they did because numbers were too great and we weren’t about to leave. Well, many of these occupations ended up somewhat cut off, without the population's support. (INT 17)

The clampdown against the occupations came to a head in 1977 when the government declared that those resisting eviction would be prosecuted, with a maximum sentence of two years in prison for anyone who engaged in forceful protest, and heavy fines for the resident associations or committees that supported the evicted (Bandeirinha, 2011). The general orientation of housing policies also changed: austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund in 1977 and 1983 were particularly significant in decreasing government funding for public and social housing (Bandeirinha et al., 2018). Nevertheless, local efforts frequently managed to stop the evictions of occupying families, and, in many cases, occupations continued to be legalised (J. H. Santos, 2014). Yet the general line was one of a hardening of the line against the occupations. In current times, even though the right to housing is enshrined in the Portuguese Constitution, international human rights law and the national framework law on housing (Law no.83/2019), occupiers are met with the full force of the law, which frequently leads to evictions (Saaristo, 2022b). Public opinion also tends to be against the occupations:

So, we need to see what we can do because, at the moment, in my understanding, we don’t have the support of the population like we had back then, do we? [The collective] can mobilise people and does a truly excellent job, but we’re not living in a revolutionary time where things like this are accepted, are we? We need to educate society, don’t you think? So that these occupations might be seen as fair. (INT 17)

In the case of 2 de Maio, the resident committee continued to mobilise to get their occupations recognised legally and issue title deeds to occupiers, going en masse to the Salazar Foundation, in the city centre, to make their case. The Statute of the Salazar Foundation is unclear regarding housing policy, but the occupiers expected that they would eventually be granted title deeds for their homes. This is quite reasonable, considering how housing policies of the dictatorship had demonstrated a strong preference for private ownership (Baptista, 1998) and thus promoted solutions such as propriedade resolúvel, ‘resoluble ownership’, a regime through which the residents gradually acquired their properties by paying instalments over 25 years.

I once went to a meeting with Senhora Isabel at Braancamp [Salazar Foundation] […] I demanded she sign the tenancy agreements, which she was reluctant to do. I was wearing clogs. I grabbed a clog and hit the desk with it because I had the strength and resolve to fight for what I wanted. I took my clog, slammed it down on the desk in front of her and told her, ‘Oh, Senhora Isabel, put our names on the contract because I’m going to tell people to deposit money!’ At first, she’d shown us a piece of paper addressed to the Resident Committee saying that the houses would be ours after 25 years. But when things took a turn for the worse, Senhora Isabel had all the paperwork burnt; we were left without a copy of the document. (INT 1)

The interviewee’s version of events was not exactly what happened, however. Instead, the properties were passed first on to the management of Casa Pia, a Portuguese religious educational institution: Decree-Law no. 295/78 of September 26 shut down the Salazar Foundation and assigned the real estate assets of the 2 de Maio neighbourhood to the Casa Pia de Lisboa. One year later, Law no. 12/79, of April 7, established that neighbourhood ownership should be passed on to the City Council of Lisbon, but this only happened in 1996 (Antunes, 2017, p.241). As pointed out by Antunes (2017, p.246), agreements between resident committees and city councils often had no legal grounding in terms of existing legislation. This led to several ambiguous situations in terms of the conditions on rents to be paid or the possibility of passing on or selling the apartments to family members, even if many of the PREC public or semi-public housing occupations - like in the case of 2 de Maio - are now formally recognised as council housing, managed by the municipal housing company Gebalis. Until now, many residents have resisted eviction and will soon be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the occupation.

6. Discussion

The existence of grievances, i.e. extreme housing precarity before the Carnation revolution is a fact that PREC housing movement literature generally seems to agree upon: the abject housing conditions in informally produced neighbourhoods are undeniable. This factors in with the general failure of social development indicators recorded during the dictatorship, with high poverty, child mortality and illiteracy rates. People were frustrated with their living conditions, and one thing that is clear from the 2 de Maio interviews is how there was a spontaneous rush to join the groundswell of occupations. As pointed out by other authors, this could indeed be because of shared everyday experiences, which enabled the building of collective action frameworks, which, in turn, helped to inform people’s perceptions of the occupations as being legitimate. In addition, the dictatorship had already begun construction work on the neighbourhood, which had created both a sense of expectation and of resentment due to the concern that the neighbourhood’s housing might not be intended for the deprived population living nearby but targeting other population groups, such as civil servants working for the dictatorship.

People heard that others were ‘grabbing’ homes for themselves, speaking of the act in the same terms as, for instance, someone who had stumbled across something on the street and decided to keep it for themselves. However, these were not the same people who had set the occupation movement in motion, but rather were joining an ongoing wave. Even so, the transition in behaviour from being servile and obedient to the regime during the dictatorship, to suddenly joining an occupation movement is nonetheless remarkable, implying a very strong and sudden change in the interviewees’ perception of their possibilities of agency. This revolutionary spirit seems to have taken over very swiftly. Our interviewees, except INT1, had little background in political mobilisation and activity. INT1, on the other hand, was already a spokesperson for cleaning staff at their workers’ union, with a considerable track record in leadership and mobilisation. While our interviews also allude to previous experience in local organisation and political participation, this does not come across clearly. However, the interviewees mentioned the role of the student population in the mobilisation, who encouraged the people to demand access to housing and seemed to have had a significant role in bringing the residents of precarious neighbourhoods to the street. Furthermore, the mention of alliances with other lower-income neighbourhoods points to the existence of particular factions organizing locally within the neighbourhoods.

It is also clear that the impact of the political climate was decisive: a case in point being that the police forces were not sent to interfere when the initial occupation occurred. From here, the occupations progressed to the next phase: as the occupied apartments were unfinished, there was immense construction work still to do. In the course of this, resident commissions were of vital importance in coordinating the action. Solidarity between residents was what enabled them to ‘keep’ their homes: as these had to be constantly under guard, with someone always keeping an eye on the apartment, which was only possible because the occupiers mobilised together to support each other, sharing food, building materials, as well as defending properties against intruders. To this end, the support of COPCON was a considerable advantage as they brough physical strength. Without the support of military organisations such as these, occupiers’ fight would have to be even more hands-on.

Ferreira (1986) described how occupiers sought to legally register and defend their right to the apartment they occupied. The State’s stance towards occupations played a central role in this. Because of a law requiring landlords to rent out any vacant property, whenever this failed to happen, any occupiers seemed to have gained the moral high ground for their actions. In this case, even the April 1975 decree-law on the ‘legalisation of occupations’ seemed insufficient, even if it provided an avenue to legalising the occupation in some way. After November 1975, the political climate changed drastically, closing the door on any political opportunity for the legalisation (Downs, 1980). The struggles of 2 de Maio residents did not, however, end, as they, with the guidance of INT1 and other members of the Resident Committee, embarked on a journey to legalise their occupations as their own private property. In many other cases, this did take place through the drawing up of rental contracts, and the council housing model was also eventually the one that took precedence in 2 de Maio. Contrary to what Ferreira (1986) had observed, the residents of 2 de Maio did not aim for the state’s recognition of any appropriation by these means. Having a rental contract did not meet the goals of many of the interviewees, who made it clear they would rather be in possession of the title deed to their apartment through the option of ‘resoluble ownership’. However, in the course of the interviews, there is no indication that such a stance would be the result of a conscious challenge to the property and ownership relations in Lisbon. The motivation was rather a hope that occupiers had for their families’ futures. Hence there was not an explicit narrative of reclaiming urban or housing commons, although the occupiers did manage to break a cycle and reclaim access of urban working classes to housing at a specific moment in history.

7. Concluding Notes

The aftermath of the Carnation Revolution, imbued with radical views on social organisation and housing rights, is an unrepeatable phenomenon. Popular mobilisation, supported by large swathes of the general public, led to a perception of the occupations of vacant dwellings based on a sense of spatial justice, leading to a law that declared: ‘as long as there are people without homes, it is unacceptable that there should be homes without people’. The occupation movement vanished after the 1970s, but it is generally argued that the urban movements that the occupations were part of paved the way for the transition of Portugal to democracy. The PREC has been credited with pushing through many social and political reforms that were incorporated into the Portuguese Constitution of 1976 (Accornero, 2019; A. C. Pinto, 2010), including the right of all citizens to decent housing (Nunes & Serra, 2004). Yet critics point out that when the representative democracy system was set up, the experiments of participatory democracy were being effaced, and the memory of acts of social and political participation has been erased (Nunes & Serra, 2004). Many of the promises of PREC were reneged upon, seeming to be nothing but hot air. It is also significant, as Ferreira (1986) points out, that PREC-era housing occupations did not succeed in unleashing a wider questioning of the urban property and land ownership climate, which could have led to urban reform. Despite being enshrined in the Portuguese Constitution as a fundamental right, it has been observed that the right to housing has been successively placed in jeopardy, and over 50 years, society’s perception of the phenomenon of occupations has changed, as well as the capacity to find allies and supporters.

The fact that the PREC-era occupations were driven by housing precarity brings to light the fact that deprivations alone are insufficient to legalise occupations in the eyes of public opinion, let alone the state. The potential legitimisation of occupations seems to strongly depend on the political stance of those in power: those with the power to either simply repress occupations or, conversely, to engage in dialogue with occupiers to seek solutions together. The PREC period provided a one-of-a-kind context: the experience of overthrowing a dictatorship led to a lack of willingness on the part of the military and the Junta to repress the swell of proletarian mobilisation. The revolutionary atmosphere provided a ripe political opportunity for direct action to access housing, yet the willingness of state actors to negotiate most certainly also depended on the negotiation power of the occupiers as well as the support networks they had been able to build to defend themselves. The creation of networks and alliances beforehand, in ‘pioneering’ neighbourhoods at the forefront of occupations enabled rapid action to be taken, although, superficially, the occupations appeared to occur spontaneously. Furthermore, right after the occupations, residents began to organise themselves quickly and, through collective action, keep the momentum of the occupations going.

Today, the landscape is drastically different. The years 1974 and 1976 in Europe were characterised by the model of social democracy, state intervention, and the end of colonialism, colonial wars, and the dictatorship in Portugal. The 2010s and early 2020s have seen repeated announcements of the end of the neoliberal economic model, yet there is no end in sight, as alternatives to neoliberal capitalism still struggle to gain traction and stability. Housing and the real estate market have become heavily financialised, to the extent that housing is now seen more as a financial asset rather than a fundamental human right (Rolnik, 2019). As for housing instability, the current era has been marked by a rise in homelessness among the lower and middle classes, as the market has failed to provide housing for all. Additionally, in many countries, social housing systems and safety checks have been dismantled. In Portugal, the housing crisis seems only to have been exacerbated as social housing - representing only 2% of the residential stock nationwide - did not develop into a meaningful response to counter the effects of the increasing commodification and financialisation of housing. Newer housing policy proposals have failed to provide an effective response (A. C. Santos, 2019). The climate today offers a vastly different political environment in face of the occupations still happening in council housing estates in Lisbon when compared to PREC-era occupations. The context today provides less political opportunities and affects the potential for building radical political subjectivities (Saaristo, 2022a). A broader 21st-century occupation movement in Portugal has yet to see the light of day.