Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic disorder,1 that has a prevalence of 20%, being the most common gastrointestinal diagnosis in the United States.2 GERD is caused by the retrograde movement into the esophagus of gastric acid and pepsin. This retrograde movement is responsible for the GERD symptoms, and it may injure the esophageal mucosa. The chronic injury of the esophageal mucosa induced by recurrent reflux episodes will lead 10-15% of the patients to develop Barret’s esophagus (BE).3 Interestingly, the duration of reflux, and consequently of symptoms, is the most important factor determining the development of BE.4 From the patients with BE, 0,12% will have esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC).5 Although the specific cellular events that cause differentiation are unknown, the increase of length of the BE and the presence and grade of dysplasia are the most important predictive factors for the development of EAC.6

GERD symptoms include esophageal (heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia) and extraesophageal (chronic cough, hoarseness, chest pain) symptoms.3,7 These symptoms may occur any time throughout day and night. However, night symptoms, which occur in 74%-79% of patients with GERD8 are associated with more severe disease and complications.9 The high rates of night-time symptoms might be associated with decubitus10 and physiologic changes that occur during sleep11 which include: i) increase in basal gastric acid secretion,11 ii) decrease in the gastric emptying,12 iii) decrease in basal upper and lower esophageal sphincter pressure,13-14 iv) decrease in primary and secondary esophageal peristalsis,15 v) decrease in saliva secretion16 and vi) decrease in swallowing responses.17

Although the primary diagnostic approach to GERD is through clinical symptoms, a diagnostic test is necessary. According to the Lyon consensus 2018, pH-impedance monitoring is the gold standard for the detection and characterization of reflux episodes.18

Studies clearly indicate that the reduction of gastric acid production by antisecretory agents, namely proton pumps inhibitors (PPI), improves GERD symptoms1 and esophageal mucosa modifications. This occurs because inhibition of gastric acid production decreases the potential of acid damage to the esophagus. Additionally, the elevation of gastric pH inhibits the conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin.19

PPIs are inactivated by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in the liver. Considering that there are different alleles of CYP, leading to extensive, intermediate, and poor metabolism of PPI, there can be different clinical responses to GERD treatment with PPI.20 Thus, maintaining plasma PPI’s levels for longer periods is paramount to ensure a steady inactivation of proton pumps. This may imply that PPI once daily (od) might not preserve therapeutic acid suppression in all patients. Therefore, the best regimen of PPI is primal to assure a maximum control of GERD effects, including symptoms and complications.

General practitioners (GP) are many times the first medical doctors to attend to a patient’s GERD symptoms. Therefore, GP must have state-of-the-art information on how to best treat these patients, and on how to achieve the greatest symptomatic relief and the lowest complications. Although the decubitus, the increase in the basal gastric acid secretion, and other physiologic changes that occur during sleep potentiate GERD,1 initial PPI regimen is usually indicated for od dosing before breakfast.19 Consequently, we carried out this evidence-based review (EBR) with the purpose to assess the current evidence on the best PPI regimen to GERD control, regarding the circadian pattern of GERD symptoms.

Methods

To perform this EBR, the Braga and Melo strategy des-cribed in 2009 was followed.21 The population (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), outcome (O) model (PICO) was used to achieve a Disease-Oriented Evidence that Matters (DOEM).22 For the inclusion criteria of the articles selected for revision, population was defined as adult individuals with GERD symptoms or healthy volunteers; intervention as PPI in the morning; comparison as PPI in the evening; and the outcome was a decrease of symptoms and increase in esophageal or gastric pH. We excluded articles with pediatric populations, prior gastric surgery, or taking other medications directly affecting the acid production. This strategy was followed to assess the best PPI regimen that would improve GERD patient’s symptoms, and, thus, contribute to better medical practice.

This EBR was oriented to the effect of PPI on pH because the pH-impedance monitoring is the gold standard for detection and characterization of reflux episodes,18 and that in many cases patients may have esophageal consequences without symptoms, namely during night-time.1 Additionally, optimal intragastric pH control is the key to effective treatment.23

Thus, we select the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) words from the MeSH Database of PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh). The MeSH words chosen were ‘proton pump inhibitors’, ‘gastro-oesophageal reflux’, GERD, and pH.

We used the selected MeSH words to search for synopses, guidelines, meta-analysis, systematic reviews, and original papers, published after 2008 in the databases MEDLINE, National Guideline Clearinghouse, NHS Evidence, Canadian Medical Association, TRIP Database, The Cochrane Library, DARE, and Bandolier in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese.21 The following results were obtained:

NGC - National Guideline Clearinghouse (http://www.guideline.gov/): site shows the following information “sites were taken down on July 16, 2018, because federal funding though AHRQ was no longer available to support them”. National Institute for Health Care and Excellence of the NHS (https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/): 102 results were obtained, seven were chosen after title analysis, with one remaining after abstract reading. None was used for this EBR because did not met de inclusion criteria of this EBR. Canadian Medical Association Practice Guidelines InfoBase (http://www.cma.ca/cpgs): zero results were obtained. DARE - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/): zero results were obtained. Bandolier (http://www.bandolier.org.uk/): zero results were obtained. Evidence-Based Medicine online (http://ebm.bmjjournals.com/): two results were obtained, but they were not chosen after title analysis, due to the fact that they did not met de inclusion criteria of this EBR. The Cochrane Collaboration (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/): 17 results were obtained, three were chosen after title analysis, none was used for this EBR after abstract reading because they did not meet de inclusion criteria of this EBR. PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed): 2,425 results were obtained, 1,293 were published after 2008, 15 were chosen after title analysis, with four remaining after abstract reading, being three of these included in the EBR after paper analysis. Studies that did not met de inclusion criteria of this EBR were excluded.

It was also performed a search in the Índex de Revistas Médicas Portuguesas (www.indexrmp.com), with the following keywords: “inibidores das bombas de protões”, “refluxo gastroesofágico”, DRGE, pH. Zero results were obtained.

Thus, the search retrieved a total of 2,546 articles, from those, only three were included in this review. The remaining 2,543 were rejected because they did not meet the inclusion criteria of this EBR.

The authors extracted the following variables from each study: chosen PPI, dosage, and schedule, measured PH value, number of reflux episodes and period of the day, follow-up time, and sample size.

The articles and results were cross-analyzed between the two authors; discrepancies were discussed between authors and resolved by consensus.

To assess the risk of study bias, the authors used the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.

To evaluate the evidence level and the strength of a recommendation, the American Family Physician scale was used (Strength Of Recommendation Taxonomy - SORT).22

Results

Due to the critical importance of the PPI regimen, several studies were made to determine the better dosage and regimen to control GERD and its symptoms.

In 2009, Bajbouj et al.24 designed a prospective study with 138 patients, which received 40mg esomeprazole (30 minutes prior to breakfast) or 40mg esomeprazole twice a day (bid) for up to three months. Results indicated that, after a four-week treatment, most patients with 40mg esomeprazole bid become free of symptoms (53.2%) or had a significant decrease of symptom intensity and frequency (84.4%) when compared with 40mg esomeprazole od prior breakfast. Moreover, these results were associated with a decrease in relative acid reflux time and acid reflux events (mean number of reflux events: 64.3 vs. 115, CI95%, p<0.001, level of evidence=1).24

Ashida et al. (2011)25 published a Japanese multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, double-blind trial work, enrolling 20 patients, in which they evaluate the effect of a four-week treatment with either rabeprazole 5mg/day or 10mg/day, after breakfast for four weeks in the severity of heartburn symptoms and esophageal acid reflux. The severity of heartburn symptoms was characterized using a patient-defined four-point scale and esophageal acid reflux was determined by 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring,

The authors reported a significant association between the number of acid reflux episodes and the number of heartburn episodes (r=0.44, P=0.042). Additionally, the median change from baseline to the on-treatment median of the number of acid reflux episodes and the percentage of time at pH<4.0 was greater in the rabeprazole 10mg group than in the rabeprazole 5mg group (-18.0 vs -44.0 and -2.50 vs -6.60, respectively). However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups (CI95%, P=0.077, P=0.377).25

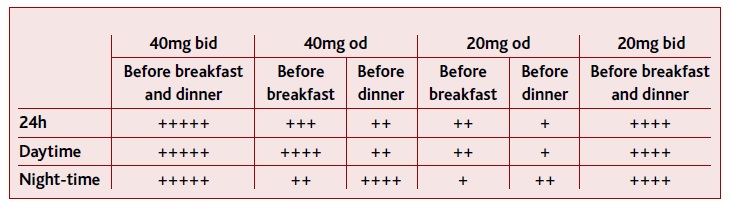

In 2010, Wilder-Smith et al.26 design a study to determine the better dosage and regimen to control GERD and its symptoms (Table I). This study was performed through a randomized seven-way crossover study in 33 Helicobacter pylori-negative healthy volunteers, conducted at a single center in Switzerland. Using different dosages of esomeprazole and different regimens with each regimen taken for five days, they studied daytime and night-time acid inhibition in healthy volunteers.26 When observing intragastric pH over the 24h, esomeprazole 20mg od before breakfast achieves better results than when taken before dinner (CI95%, P<0.05) (Table I). However, when observing intragastric pH during nigh-time, esomeprazole 20mg od before dinner achieves better results than when taken in the morning26 (CI95%, P<0.05) (Table I) (level of evidence=1).

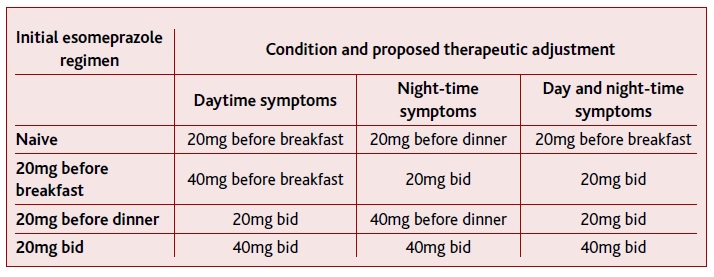

TABLE I Summary of the results obtained by Wilder-Smith et al. 2010 on gastric pH>4 depending on the esomeprazole dosage and regimen

(+) indicate the level of acid inhibition, from the lowest (+) to the highest level (++++).

When increasing the dosage to 40mg per day, 20mg bid significantly increased time with intragastric pH > 4 over the 24h period, in comparison with esomeprazole 40mg od taken before breakfast, before dinner, or at bedtime26 (CI95%, P<0.05) (Table I) (level of evidence=1). Additionally, in nigh time pH > 4, 20mg bid also presented better results than 40mg od taken before breakfast, but not when taken before dinner (CI95%, P<0.05) (Table I) (level of evidence=1). When 40mg od was taken before dinner, this did not present different results than when was taken at bedtime, in any observation (level of evidence=1).

Finally, esomeprazole 40mg bid had superior acid inhibition over the 24h period, daytime, and night-time periods, when compared with 20mg bid26 (CI95%, P<0.05) (Table I) (level of evidence=1).

Conclusions

One of the first-line therapy for patients with GERD treatment is lifestyle modifications.27 However, these measures are not always enough for disease control, being necessary to use antisecretory agents. PPI is the first-line drug for GERD treatment.

Studies have shown that patients with significant night-time heartburn seem to have more excessive gastroesophageal acid reflux compared with those without night-time heartburn.23 Additionally, two of the studies analyzed here indicate a relation between heartburn episodes and acid reflux episodes. Moreover, the reduction of gastric acid production improves GERD symptoms.1 Therefore, the results obtained through the measurement of gastric pH may be used to extrapolate the effectiveness of PPI regimens on the symptomatic control of GERD.

When considering different PPIs, esomeprazole presented the most rapid action when compared with rabeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole on intragastric pH > 4.31 Esomeprazole also had improvements in erosive esophagitis healing when compared with omeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole.19 Thus, and although every PPI has a good effect on the percentage time of intragastric pH > 431 and in the relief of symptoms19, it seems that esomeprazole may be a possible optimal initial therapeutically approach to GERD.

The results obtained here seem to indicate that the timing of proton pumps inhibitors intake should be associated with the symptom’s timing. Thus, for an initial approach, and for an overall effect, PPIs should be ta-ken od in the morning prior to the meal. These results are in line with previous ones that indicated that morning PPI’s regimen has better results when taken before breakfast.28 Thus, in patients that present signs and/or symptoms of GERD, the therapy may be initiated with esomeprazole 20mg od before breakfast (Table II).

Considering that the results showed that od before dinner regimens present better results in night-time gastric pH control than od before breakfast regimens, in patients with initial night-time GERD symptoms, the therapy may be initiated with esomeprazole 20mg od before dinner (Table II). Bedtime esomeprazole had no differences when compared with before dinner intake. Considering that PPIs inhibit only active pumps, and that proton pumps are not greatly stimulated during the sleeping period19 bedtime regimens with delayed-release PPI (as esomeprazole) seem not to be advised, with before the evening meal regimen being preferable.

The work of Wilder-Smith et al., (2010) indicate that despite the results obtained for 24h pH, esomeprazole 20mg bid did not present a difference in the day-time pH when compared with esomeprazole 40mg od before breakfast, nor present a difference on night-time pH when compared with esomeprazole 40mg od before dinner. Thus, and considering that patient’s compliance to the treatment is fundamental, if patients under 20mg of regimens continue to maintain their initial symptoms, PPI should be increased to 40mg, maintaining the intake schedule (Table II).

When PPI is taken bid, inhibition of gastric acid secretion is quicker and more complete, due to the fact that more active proton pumps are exposed to the drug.19 Taking into account that the studies described here indicated that bid regimens had better results than od regimens in the overall 24h pH, patients under od PPI before breakfast regimen (due to day-time symptoms), or od PPI before dinner regimen (due to night-time symptoms), should change their regimen for bid intake if they start to have 24h symptoms (Table II).

Additionally, and considering that i) night-time GERD can occur without symptoms,29 ii) patients with sleep disturbances have a higher percentage of esophageal acid exposure,30 and that iii), maintaining plasma PPI’s levels for longer periods is necessary to ensure a steady inactivation of proton pumps,20 in patients under before-breakfast od regimens due to initial day-time symptoms, that start to have possible signs of night GERD, as sleep abnormalities, PPI should be increased to 20mg bid.

Considering that 40mg bid had better results than 20mg of esomeprazole bid if patients taking 20mg of eso-meprazole bid maintain symptoms, dosage should be increased to 40mg, maintaining a bid regimen (Table II).

The studies presented here have in total 193 subjects, which may be short to delineate a recommendation. Notwithstanding its methodological advantages, when writing an evidence-based review, one must take into consideration that, despite following all the methodological recommendations, there is always the possibility that some relevant papers may not appear in the search’s results, due to the more restricted criteria of search, when compared to a classical review, which has broader search criteria. This characteristic of an evidence-based review should be taken into consideration when planning and discussing one. Thus, also in this EBR, some works, which contribution might have been relevant for the discussion, may not have been captured by the search made with the chosen MeSH words.32-36 Although, in this case, these works seem to corroborate the ones presented in this EBR.

Using the SORT algorithm for determining the strength of a recommendation, we consider that the results obtained with this EBR in the optimization of PPI intake regimen have a C-level recommendation, based on the consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence obtained, which may help improve patients symptoms, quality of life, morbidity, and ultimately their mortality. However, our recommendations are based on a scarce number of studies (three studies), not allowing recommendations with a high level of certainty.

Although these results indicate improvements in patient outcomes, the primary endpoint was a physiologic one (gastric pH), which does not allow for A or B-level recommendation. Thus, there is a need for more robust randomized controlled studies, to better understand the relation between the multiple possible PPI regimens, acid suppression, and control of GERD symptoms.

Additionally, despite the recommendations here presented, the long-term use of PPIs should be addressed with caution. Recently, Brusselaers et al. showed that the long-term use of PPI may be associated with the development of EAC,36 reinforcing that this, as other bio-medical issues, should be in constant assessment.