Introduction

Acute pharyngitis is a common diagnosis in primary care facilities and emergency departments. It is in most cases of viral aetiology, benign and self-limiting, with an incidence peak during the winter.1 The bacterial pathogen most frequently involved is Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes), also known as group A β-haemolytic streptococcus (GAS). It is estimated to account for 20% to 40%2 of cases of acute pharyngitis in children and 5% to 15% in adults. 3

Epidemiological context and clinical presentation alone are not enough to establish the aetiology diagnosis. 1 Throat swab culture is the gold standard for the diagnosis of bacterial pharyngitis. 2,4 However, the delay in obtaining results makes it impractical to use in clinical practice.

Rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs) are a useful alternative providing an immediate indication of the presence or absence of GAS in children and adults presenting with acute pharyngitis. 1-2

RADT does not require any special equipment and can be performed at the point of care with a throat swab. 2 Unfortunately, it is not always accessible for physicians to use in Portuguese primary care facilities.

Although viral is the most common aetiology, antibiotic therapy is frequently prescribed to treat acute pharyngitis. 5 The belief that antibiotic promotes faster recovery of symptoms, the fear of early and late complication from GAS infection such as peritonsillar phlegmon and heart disease, and the pressure from the patients to obtain an antibiotic prescription are some of the reasons that explain the overuse of antibiotic in these cases. 6-7

The consequences of inappropriate antibiotic prescription are well known, being the control of infections and the reduction of antibiotic resistance a priority health goal in many countries, including Portugal. Therefore, many national and international guidelines recommend testing for GAS before antibiotic treatment in patients with clinical presentations suggesting GAS infection. Unlike the Directorate-General of Health of Portugal (DGS) guidelines, most European countries recommend the use of a validated score (e.g., Centor Score). 1-2,4

This study aims to describe the implementation and feasibility of RADT in a primary care setting, in the Lisbon metropolitan area, and its impact on antibiotic prescription. Secondary goals include the evaluation of possible associations between symptoms and RADT results.

Methods

Study population and sample

Between 28th October 2019 and 12th March 2020, patients presenting with an acute sore throat at USF do Parque, a primary care facility in Lisbon, were eligible for this study. Exclusion criteria consisted of recent antibiotic prescription, scarlatiniform rash, suppurative complications such as a suppurative abscess, or recent use of a streptococcus A RADT. To estimate sample size (n=93) we used the number of diagnoses of pharyngitis from October 2018 to March 2019 (n=121), a confidence limit of 5%, and a hypothetical expected proportion of 50%.

Data sources: questionnaire and RADT tests

We purchased 140 OSOM® Strep A tests, with a 96% sensitivity and 98% specificity. In real-world settings, the sensitivity of these tests showed to vary between 88% and 98%, and specificity between 78% and 100%, based on a Cochrane review. 2 RADT was performed by nursing staff that was instructed on how to collect the samples one week before the beginning of the trial. Every patient enrolled had an evaluation questionnaire filled out by the physician with anamnesis, physical evaluation, and the clinical impression which included four categories: Clearly Viral, Probably Viral, Diagnostic Doubt, and Probably Bacterial, and intention to prescribe an antibiotic. The second part of the evaluation form was filled out by the nurse describing the specimen collection process. We applied 136 questionnaires and performed 133 RADT.

Whenever there was a strong belief of bacterial pharyngitis and a negative RADT was obtained, physicians were allowed to request throat swab cultures. Clinical improvement was evaluated by a single phone call made by the physician to each patient in the study after one to two weeks from the initial assessment.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics reporting the characteristics of the study sample were presented. Categorical data were presented as total frequency (numbers) and relative frequencies (proportions). Numerical data were presented as a median and interquartile range since normal distribution could not be assumed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Associations between categorical data were tested using a Chi-squared or Fisher exact test, depending on the expected counts per cell (if <5 Fisher test was used). Associations between two subgroups of independent numerical variables were assessed using an independent Student’s t-test, of normally distributed data. Differences in non-normally distributed numerical data used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

The main outcome was the proportion of antibiotic prescriptions avoided, estimated as the number of times physicians changed their intended prescription following a negative RADT result. Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals were estimated for this proportion. To test the association between the a priori antibiotic prescription and the test result, we performed a chi-square test. The sensitivity and positive predictive value of the anamnesis and physical exam to identify positive RADT tests were estimated among the cases with viral or bacterial clinical impressions and diagnostic doubts were excluded from this analysis.

To estimate associations between clinical presentation signs and symptoms and the test result we run a logistic regression, using a bidirectional stepwise method to select variables. The best-fitted model was chosen using the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC).

All statistical analyses were performed using R, v. 4.0.3. A p-value inferior to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing values in the test result were excluded from the analysis.

Results

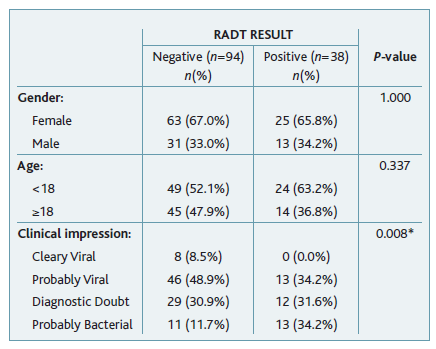

We enrolled 136 patients, 66.9% (n=91) were female and 55.1% (n=75) were under 18 years old (ages between one and 86). In 82.3% (n=112) of the participants RADT was easy to perform and in 15.4% (n=21) it was difficult to perform. Of these, 19 were under 18 years old and three were adults. Due to the patient’s lack of collaboration, in 1.5% (n=3) of the participants, it was impossible to perform RADT, two patients were four years old, and the other was 39 years old. Of the 133 RADTs performed, 97.7% (n=130) were easy to interpret. The positive test rate was 28.6% (n=38) and 0.8% (n=1) was inconclusive (Figure 1, Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of patients (n=132) and clinical impression according to RADT result (positive/negative)

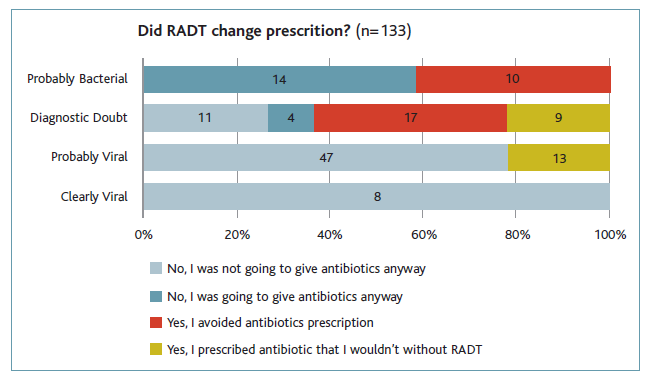

There were 24 patients classified as probably bacterial, having 13 (54.7%) of them positive RADT. In seven out of 11 patients with negative RADT, throat swabs were prescribed: four were negative, two were not performed because of the patient’s clinical improvement, and one of them was positive for S. dysgalactiae spp equisimilus. Thus, in this group, RADT avoided the prescription of antibiotics in 10 cases.

In the 41 patients that were classified as diagnostic doubt, an antibiotic prescription was avoided in 17 cases, since the physician changed the decision after a negative RADT. In nine patients that wouldn’t receive antibiotics, a positive RADT result led to antibiotic prescription.

There were 60 patients classified as probably viral. Of those, 13 had a positive RADT and antibiotics were prescribed. Eight patients were classified as clearly viral, all had negative RADT and no prescription was changed.

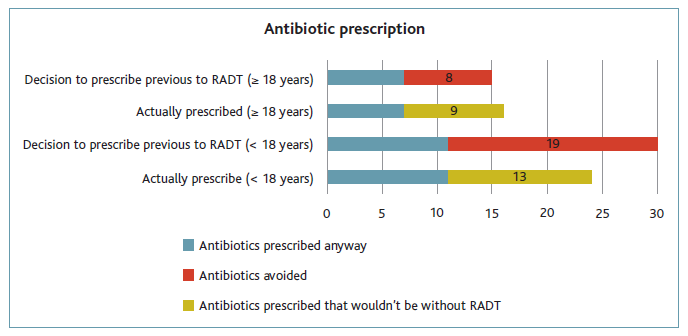

To summarise, from the 133 patients diagnosed with acute pharyngitis, antibiotics were going to be prescribed in 45, should RADT not be used. After the test result, antibiotics were avoided in 27, and 22 patients have prescribed an antibiotic because of a positive RADT. From the total of patients that performed RADT (n=133), the amount of antibiotic prescriptions avoided was 20.3% (95%CI, 13.8%-28.1%). The previous intention of prescribing an antibiotic was not associated with a positive RADT, in a statistically significant way (p=0.119) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 3 Relation between previous intention to prescribe antibiotics and antibiotics prescribed, in adults (≥18 years) and paediatric population (<18 years).

It was possible to make a total of 116 contacts to assess clinical status and in 91% of them (n=105) the patients mentioned improvement. From the patients for whom RADT changed prescription and antibiotic was not given (n=27), six reported no improvement: one was still under study by an infectiology clinic by the time of the contact, one had taken an antibiotic prescribed outside the study and three had other diagnosed clinical entities causing the symptoms, such as pharyngitis caused by another strain (n=1), pneumoniae (n=1) and acute otitis media (n=1).

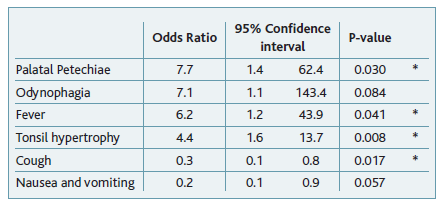

In the multivariate-adjusted model (Table 2), the only symptoms that were significantly associated with a positive RADT result were tonsil hypertrophy (95%CI, 1.6-13.7), palatal petechiae (95%CI, 1.4-62.4) and fever (95%CI, 1.2-43.9). Cough was associated with a negative RADT result (95%CI, 0.1-0.8). The positive predictive value of clinical impression to identify bacterial pharyngitis was 54.2% (95%CI, 32.8%-74.5%) and the sensitivity was 50.0% (95%CI, 29.9%-70.1%).

Discussion

This study assessed 136 patients that presented with acute pharyngitis in a primary care center, from 28th October 2019 to 12th March 2020. RADT was performed on 133 patients in line with the previously established protocol. RADT was easy to perform and interpret in most cases (82.3%) by the nursing team, with only one inconclusive result. It was possible to include 98.0% of the patients presenting with symptoms compatible with pharyngitis and integrate the data of clinical impression and decision to prescribe antibiotics, before performing RADT. These data allowed us to evaluate the impact of the test on antibiotic prescription.

The study results allowed us to conclude that performing RADT in a primary care facility is relevant since it led to the prevention of antibiotic prescription in 27 patients (antibiotic avoidance of 20.30% with statistical significance), which is in line with other studies. 8-11 Furthermore, it allowed 22 patients with bacterial pharyngitis to be treated with antibiotics that otherwise wouldn’t.

Above all, the results of this study suggest that performing RADT is especially important when the physician’s interpretation based on clinical presentation is classified as diagnostic doubt or probably bacterial, as supported by different studies. 7,12-13 Furthermore, most of the European guidelines for sore throat suggest that RADT should be performed if Centor Score or modified Centor Score ≥312 while others recommend RADT when Centor Score or modified Centor Score ≥2. 7,14 In addition, having a negative result on RADT can reassure the patient that antibiotics are not needed, thus decreasing the number of visits to healthcare facilities.

This study has multiple strengths. First, the community setting allows the evaluation of cases of pharyngitis that are present in primary care centers (different from previous research that was mainly in hospital settings); secondly, the use of a questionnaire allows the obtaining of data on the physician’s intention of prescribing antibiotics before the test. Also, the real-life assessment of the Portuguese guidelines can guide policy advocacy to introduce RADT widely in Portugal; finally, the access to the test was not restricted to individuals with a Centor Score higher than a cut-off of 2 to 3 points but to all individuals presenting with a diagnosis of acute pharyngitis, therefore providing more information than previous studies.

This study presents some limitations. First, due to the small sample size (n=133), our study is more subject to random error, limiting the precision of our results. Secondly, a selection bias could be present due to the sample selection methods. Here, individuals who did not present at the primary care center could not be included in the study. These individuals might represent a population with mild symptoms and viral pharyngitis that don’t seek medical care. Therefore, our results for avoided antibiotics might be overestimated. A misclassification bias may be present since subjective methods were used to categorise the patients into a clinical impression before RADT, instead of using a more objective method such as Centor Score. However, this is not a differential bias since the clinical evaluation to classify the cases in terms of probably viral/bacterial was before the test, and physicians were not externally influenced. Research that additionally considers standardised methods for categorisation of the clinical presentation (e.g., Centor Score), increases data reliability, therefore helping clarify the impact of RADT in an antibiotic prescription, allowing the additional reproducibility of the study and comparability of results.

Considering that people seeking medical care for pharyngitis in primary care centers are homogeneous on a national level and the DGS guidelines are applied nationally, it is acceptable to generalise our results to the Portuguese reality.

Conclusions

Antibiotic resistance has worsened in recent decades. 15 Thus, it’s imperative that antibiotic prescription only occurs when a bacterial infection is present. Our study showed that RADT use in cases of pharyngitis is easy to implement in a primary care setting in Lisbon and led to a 20.3% reduction in antibiotic prescription. Tonsil hypertrophy, palatal petechiae, and fever were significantly associated with a positive RADT result, and cough was associated with a negative RADT result. This primary care unit, as many others in Portugal, usually does not have access to Streptococcus A RADT, meaning that unless the physician requires swab cultures, the antibiotic prescription is only determined by anamnesis and physical examination. Considering the DGS guidelines, the test should be available in every primary care center and be performed when there is a strong suspicion or doubt of bacterial infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable contribution of the Association for Research and Development of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon (AIDFM) and all the doctors and nurses of USF do Parque.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, RA, LV, DM, CD, and VM; methodology, LV, and VM; formal analysis, RA, LV, DM, CD, RS, and LJ; investigation, RA, LV, DM, and CD; data curation, RS; validation, VM; writing - original draft, RA, LV, DM, LJ, MM, IM, and JO; writing - review and editing, RA, LV, DM, CD, RS, LJ, MM, IM, JO, and VM; visualization, RA; supervision, RA and LV; project administration, RA; funding acquisition, LV, and VM.

Funding

One hundred and forty RADTs were funded by the Association for Research and Development of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lisbon (AIDFM).

Authors’ Declaration of Contribution

All authors declare to have contributed to the elaboration of the article and agree to be responsible to the accuracy and integrity of this work.

Ethical aspects

This study was approved by the ethics committee (110/CES/INV/2019 of 20 September 2019). The authors declare the protection of persons, that all participants involved in this study have signed informed consent, and that all data are confidential.

This study ended earlier than the expected date due to the implementation of the state of emergency in Portugal, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.