Background

Dementia policy recommendations emphasise the pivotal role of primary care services for patients and their families.1-3 Notwith-standing, there is a body of evidence that dementia is under-managed in primary care. General practitioners (GPs) seem to underperform in assessing signs and symptoms of dementia, 4-5 managing associated depression, 4-5 providing information about dementia, 6-7 and assessing social support and carers’ needs. 4-5,8 There are multiple barriers to the management of dementia in primary care, including challenges related to the complex biomedical and psychosocial nature of dementia itself; gaps in knowledge and skills of health professionals, and negative attitudes; and system characteristics. 9-10

Biomedical models still dominate the understanding and treatment of dementia. This leads dementia to be seen mostly as an invariably progressive condition where little is worthwhile beyond the limited pharmacological approaches currently available. 11 This perspective conditions the help provided to persons with dementia and their families, and their ability to live better with dementia whilst struggling against its consequences. A complimentary perspective that should be considered in primary care settings focuses on valuing ‘social health’: the ability of a person with dementia to preserve their autonomy and solve daily problems, to adapt to and cope with the practical and emotional consequences of dementia, and to participate in social activities. 12

Many characteristics of the Portuguese primary care system may impact dementia care. 13 General practitioners are gatekeepers within the National Health Service, controlling access to what in many countries are called ‘specialists’ (e.g., neurologists, psychiatrists). In primary care health centres, users are grouped into ‘family files’ and most nurses work closely with GPs; how-ever, there is a lack of guidance for the functions of these nurses in many areas, including dementia, and the current electronic clinical files do not allow sharing of information. 14

General practitioners’ consultations also tend to be brief (around the recommended 15 minutes). 15 This limited time frame does not foster cognitive screening in primary care or the comprehensive follow-up of people with dementia and their family carers, as recommended in Portugal. 16-17 Finally, Portuguese GPs are allowed to initiate and renew anti-dementia drug prescriptions, but in primary care, patients have to make a full payment. Instead, out-of-pocket expenses for these prescriptions are much lower if they are prescribed by a neurologist or psychiatrist. Unlike other European countries (e.g., the UK, the Netherlands) Portugal only published its dementia strategy in 20181 and it has yet to be implemented, although definite steps are now being taken officially to tackle this delay, aggravated by COVID-19. 18 The Portuguese strategy suggests that primary care should undertake early screening for cognitive impairment, foster integrated diagnosis and management of persons with dementia in coordination with secondary care, and promote person-centred care in coordination with community services. However, this seems far from being put into practice. Recent research from our group indicated that GPs seem to contribute little to current dementia care in Portugal, 6 and that liaison between primary and secondary care is inadequate14,19 suggesting that primary care may not yet be prepared or able to implement the national dementia strategy.

The concept of ‘dementia care triads’ has been used to depict systems including the person with dementia, the family carer, and the GP, since the typical physician-patient dyad often expands to a triadic relationship as cognition declines. 20 A recent review of triadic interactions, based only on data from interviews, demonstrated their complexity and highlighted the need to resolve mismatched expectations of individual roles, encourage patients’ autonomy, and maintain continuity of care. 21 Other studies based on survey methods suggest that persons with dementia are less likely to be actively involved in conversations and decision-making as cognition deteriorates, 20,22 and coalitions between carers and doctors often occur. 23 However, it is still not clear how triadic interactions with GPs may affect dementia care provision. Consultation analysis has been used in primary care for a variety of purposes, 24-25 but to our knowledge not yet with dementia triads.

Methods

Design

A qualitative study was performed, involving the analysis of routine consultations with dementia triads (GP, person with dementia, and their family carer). This was a sequence of our previous studies on dementia in primary care, 6,14 which focused on different objectives, and the final samples overlapped.

Setting

As described elsewhere, 6,14 six practices within the Lisbon metropolitan area were selected to reflect different socio-economic characteristics.

Sampling

A contact person (GP) in each family health unit recruited the GPs. The GPs’ inclusion criteria were that they provided regular care to people with dementia. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants. 26 The GP sample comprised both genders and different durations of clinical experience. Persons with dementia were recruited by their GPs during routine appointments, regardless of their reason, according to the following criteria: 1) willingness to permit recording of their consultation; 2) dementia diagnosis according to ICD-10 DCR; 27 3) being accompanied by a consenting family carer in consultations. A purposive sample of people with dementia included both genders, individuals at different stages of dementia, and with different types of kinship with their carers. The mental capacity of the person with dementia was determined by the GPs, but lack of capacity was not an obstacle to involvement in the study provided a family member was willing to give proxy consent. All carers were family members.

The sample size needed was estimated to be 10-12 consultations using Guest et al.’s methods. 28

Data collection

All participants filled out a brief ‘ad doc’ questionnaire on demographic data and dementia-related information. Data saturation criteria were based on an initial analysis of ten consultations and on a stopping criterion of two consultations where no new ideas would emerge. 29 These criteria were met at the tenth consultation. The consultations were digitally recorded between January and November 2018; all recordings were uninterrupted and had good sound quality. The place of consultation was either the practice or the patient’s home. Consultations were transcribed and anonymised. The accuracy of the transcripts was checked by the primary author.

Data analysis

The framework method30 allowed management of the transcripts in systematic stages, improving the transparency of results.

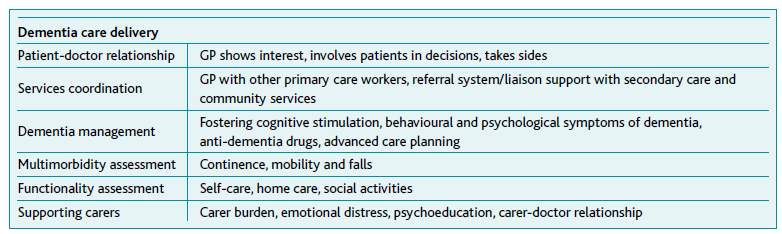

All transcripts were coded by two researchers using NVivo 12®. The initial analytical framework drew on available literature20,31-33 (see Table 1) and categories generated by the analysis of the first three transcripts, allowing for a combination of inductive and deductive analysis. An analytic framework with three themes was then developed and applied to each transcript, and differences were resolved by discussion. The transcripts and themes were translated into English by a bilingual speaker after data analysis.

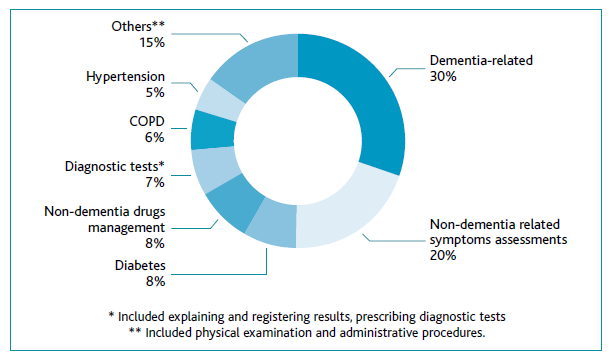

General practitioners address a variety of health concerns in consultations; 34 therefore, the length of these non-dementia discussions was quantified, guided by clinical judgment, as a proxy for the amount of time in the consultation focused on dementia (see Figure 1).

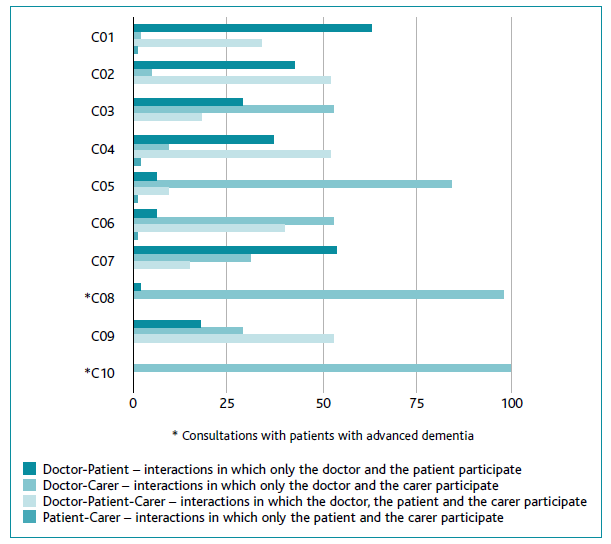

Consultation pattern was categorised as Doctor-Patient, Doctor-Carer or Doctor-Patient-Carer (Figure 2)

Findings

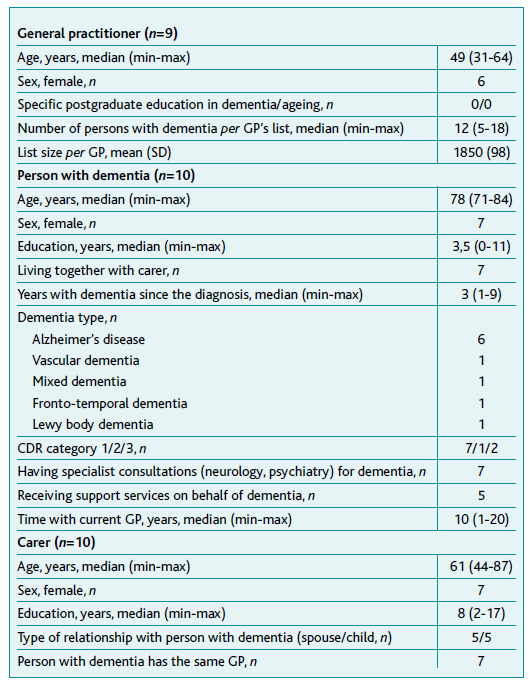

The characteristics of participants are summarised in Table 2.

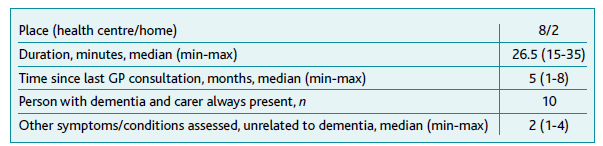

The characteristics of consultations are summarised in Table 3.

Three major themes and five sub-themes were identified and are summarised in Table 4.

Assessment of the impact of dementia on daily life

Half of the GPs enquired about sleep disturbances, agitation, and depression, from both patients and carers; although most of these assessments tended to be very brief, a few others were more extensive.

GP: And what about your sleeping? You used to sleep well, didn’t you?

Patient: Yes.

GP: How are you doing now?

Patient: Not very well since last week.

GP: Really? What happened? Can you explain?

C04

Most GPs explored the consequences of dementia with patients and carers alike. They focused almost exclusively on patients’ needs related to preparing meals and personal hygiene, disregarding their social relationships. Half of them also explored safety needs, such as medication errors and risk of falling, which seemed to be met.

GP: What about your medication? Do you take it on your own, or do they help you with that at the day centre?

Patient: I have a pill box with the days of the week.

GP: And you don’t get it wrong?

Patient: No.

GP: Don’t you get confused?

Patient: No, no.

Carer: They give her the medication at the day centre.

GP: Ah! So, the pill box is at the day centre!

C02

However, in these assessments, a few carers spoke on behalf of their relatives, and sometimes GPs went along with this pattern, despite some GPs trying to involve the patient in the conversation.

GP: (…) She goes to the bathroom alone, doesn’t she? [addresses the patient] Do you go to the bathroom on your own?

Patient: Luckily still- [carer interrupts]

Carer: She goes, yes.

GP: And do you need incontinence pants at night?

Patient: No- [carer interrupts]

Carer: No, no, but we have a few accidents because she doesn’t always realise she needs to go to the bathroom, I think she doesn’t realise (…)

GP: But she uses a little pad, right?

Carer: Yes, always!

C06

In general, the impact of dementia on carers was poorly assessed in these consultations. Most GPs did not actively explore carers’ needs. A few carers spontaneously mentioned the burden of care but GPs ignored this in half of the cases.

Carer: She really likes being at the day centre. It’s a break for me. [laughs] Even better if she was there one more day in the week… Not Sundays, but Saturdays… would be great [laughs]

GP: So… what was the medication prescribed by the neurologist?

C06

In one case, the presence of the patient in consultation seemed to have prevented the carer from expressing their difficulties in addressing the patient’s behavioural problems: a look of disapproval on the patient’s face noticed by the GP made them change the subject.

GP: What’s the most difficult thing for you?

Carer: When we tell her to do things she won’t do them.

GP: Mm-hmm

Carer: And she gets grumpy (…)

[GP assesses how the carer manages patient’s behaviour]

GP: It might help distract her with another subject (…)

Carer: Yes, but she…

GP: [addressing the patient] You’re making such a face…

Carer: Well, but she remains quite autonomous…

C05

Some GPs asked carers about their difficulties, but only when they lived together with patients. These difficulties were further explored in only one consultation, in which carer-GP interactions dominated.

GP: What’s the most difficult thing for you?

Carer: When we tell her to do things and she won’t do them

GP: Mm-hmm

Carer: Now she’s a little better, but she has days…

C05

Management of the consequences of dementia

In general, GPs’ dementia-related interventions were uncommon in these consultations. They did not regularly provide information about dementia. Only one GP briefly instructed the carer on managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and the risk of falls.

Carer: Her stubbornness.... that’s basically it, we tell her to do particular things and she decides not to do them (…)

GP: And what do you do then?

Carer: Letting her be, not making a fuss… In the beginning, we used to discuss a lot…

GP: Right.

Carer: But now, I know better…

GP: It might help distract her with something else.

(…)

GP: …Then there’s walking from the bed to the bathroom when she needs to get up during the night … Do you have any rugs?

Carer: You’re right, there’s a rug, but I’m going to take it away from there.

GP: Good, either remove or secure it.

C05

Another GP tried to provide information about the diagnosis of dementia, but then abruptly changed the topic, preventing further questions.

Carer: What is sertraline for?

GP: It’s for depression. Often, people … women in menopause and older people… the loss of cognitive abilities, memory, etc., is sometimes associated with depression, sometimes not…but we always try to help. You felt better with sertraline, but memory issues persisted. That’s why, we did the CT scan and other tests (…) The scan suggested Alzheimer’s, didn’t it? But we will see what’s going on, OK? Let’s see… The CT scan showed this, didn’t it? You also have anaemia, which got worse. Have you been eating well? Meat? Fish?

C07

While none of the patients questioned their GPs about dementia, a few carers did. One carer asked what caused their relative to have dementia but the GP was vague in their answers.

Carer: Uh ... there’s another thing that I don’t know whe-ther it had any influence or not. She used to sleep an hour a night, and this went on for years (…) She was always working hard ... and she used to drink lots of coffee to stay awake....

GP: Mm-hmm

Carer: Maybe all that influenced this...

GP: Hmm, not really, no ...

Carer: ... because she didn’t have enough sleep, and this could have something to do with the situation, right? Couldn’t it?

GP: Ah ... not necessarily.

Carer: Just trying to explain this to you, Doctor, just trying to help…

C09

On most occasions, GPs did not provide explicit emotional support either to patients or carers. Some patients expressed their difficulties in accepting the consequences of dementia in daily living (e.g. driving ability), but most GPs did not validate their feelings.

Patient: My wife keeps forgetting that she had an accident, obviously not with me at the wheel…

GP: Do you think you are still fit to drive, is that it?

Patient: I think I am, I’ll take full responsibility.

GP: So, you don’t get lost, contrary to what your wife says...

Patient: Getting lost is different… Doctor, I haven’t done thousands of kilometres, I have done millions of kilometers…

GP: You think you can drive just like you did before.

Patient: No, I do have one difficulty: road signs have been changed. But I do manage, I stop and ask for directions. I haven’t done hundreds, but millions of kilometers!

C01

Only one GP explicitly explored the patient’s psychological distress, by using prosody (changes in tone, stress, and rhythm) to convey concern.

GP: OK, so when you talk about ‘instability of thought’ what do you mean?

Patient: Sometimes it takes me a long time to catch the thread of a conversation, that’s it…

GP: Mm-hmm…

Patient: I don’t know ...

GP: OK, I understand. Look, have you been feeling sad?

Patient: Yes ...

GP: Do you feel like crying or do you sometimes cry?

Patient: Before, I used to be moved by many things, but after I took sertraline ... it was the only thing that I felt was helping me ...

C04

Furthermore, carers were always present throughout these consultations, and in some cases, both GPs and carers prevented patients from expressing their thoughts and feelings ignoring their autonomy, as was the case of the GP who seemed to collude with the carer by adopting a paternalistic attitude.

Carer: (…) I put the breakfast on the table and it stays there for two hours, getting cold …

GP: But do you eat everything cold?

Patient: Sometimes yes, but I prefer to eat it cold rather than hot because I like to pray early in the morning.

GP: Well, but cold food is not good at all Mr. X! [patronising tone]

Patient: But I have my religion…

GP: OK, but praying after eating is as valuable as praying before.

Patient: OK, but in my opinion...

GP: Yes ... it is true, but then after praying, you should warm it up a little bit, again, so that you’re not eating things cold, OK?

C03

The few carers who received emotional support from GPs participated in consultations where doctor-carer interactions dominated. Few GPs used active listening techniques to facilitate the exploration of carers’ concerns. However, one GP addressed fears regarding a patient’s diabetes treatment plan by explicitly acknowledging nonverbal communication issues.

GP: Since you’ll stop her corticosteroid within 6 days, I won’t prescribe any insulin ... Oh, I see you are staring at me…

Carer: It’s just…

GP: You became quite distressed when…

Carer: I’m… a little worried because when her glycaemia goes up to 400 I get worried…

GP: I know, I know ... but I’m tapering the dose of the corticosteroid, and that will lower the glycaemia, you know? So, there is no reason for starting another medication and then stopping it, are you with me?

C10

Most patients were taking anti-dementia drugs, but most GPs did not manage them directly (renewing prescriptions or monitoring side effects). In fact, GPs and carers understood this medication to be ‘the neurologist’s medication’.

Carer: And the medication for memory… The one from the neurologist…

GP: Exactly… It has to be prescribed by neurologists. (…)

Carer: Since there were no great results, she [neurologist] increased the dose.

GP: Donepezil? OK. So, the present dose is 10 mg/day, is that it?

Carer: Yes.

GP: Very good. And regarding other medications, what prescriptions are you going to need?

C08

Coordination within primary care, with specialists, and with social services

There did not seem to be any liaison between GPs and specialists. The GPs had to ask carers for any information about the specialists’ clinical assessments and patients’ current medication.

GP: How did the neurology consultation go? Were there any changes in the medication?

Patient: No.

Carer: … But they noticed a memory deficit. (…) She made a blood test ...

GP: What test? Do you know?

Carer: As a matter of fact, no ...

GP: Must be related to the medication… But the medication wasn’t changed… And can you tell me the name of the drug that was prescribed?

C02

No coordination with nurses regarding dementia was mentioned in these consultations; however, referrals to nurses were mentioned regarding diabetes. Although nurses were present in the two home visits, their contribution was limited to issues related to general dependency (e.g. carers’ training on lifting). No coordination with social workers was mentioned and none of the GPs made referrals to any kind of social support services.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, we analysed a small purposive sample of triadic consultations in Portuguese general practice, all of them involving a person with dementia, a family carer, and their GP. Consultations were almost twice the length of routine consultations in Portugal, even though dementia-related content took up only 30% of the consultation. These GPs addressed a variety of subjects other than dementia. 34 This might have limited dementia-specific assessments, and dementia could have influenced, by itself, the assessment of other health concerns, sometimes extending the length of consultations.

Consultation analysis captured inquiries about the impact of dementia on everyday life, management of the corollaries of dementia (need for information, medication management, psychological support), and coordination of services. These inquiries lacked breadth and person-centredness, which is of potential concern for those patients and carers whose previous consultation had occurred more than five months previously. Furthermore, there seemed to be no effective liaison between GPs and dementia specialists (neurologists, in what concerned these consultations).

The GPs overlooked dementia’s consequences for social relationships and emotional well-being, even though most doctor-patient and doctor-carer relation-ships were long-lasting. This may reflect stereotyping of dementia amongst GPs35 or their unawareness of the potential benefits of the social health approach. 11-12,36

These GPs did not seem engaged in dementia management. They provided very little information and emotional support and did not seem to manage or monitor anti-dementia drugs, despite the median time since the previous consultation being five months. The absence of formal training in dementia or geriatrics, along with the reduced number of patients with dementia registered in their lists, may compromise GPs’ confidence in addressing the challenges posed by dementia overall. Moreover, the concurrent relationship between the patients and neurologists or psychiatrists may influence these triadic interactions in primary care. 20 The fact that GPs are not allowed to prescribe anti-dementia drugs at the more favourable out-of-pocket cost will contribute to their lower engagement in dementia care, 37 and probably more so in the scenarios we found, where coordination between GPs, neurologists, and psychiatrists was not even identified. Our findings are consistent with the current predominant role of neurologists in Portuguese dementia care, contrary to other health system scenarios in Europe. The role of GPs was neglected, and psychiatrists were not even mentioned. It is possible that these persons with dementia did not have past psychiatric history nor striking BPSD symptoms, both frequently associated with a psychiatric referral or follow-up.

Carers’ assessments were, in general, poor, and sometimes limited by the presence of patients. In fact, these assessments only occurred in consultations in which GP-carer interactions dominated, suggesting that there was insufficient time to assess both the carer and the patient. Furthermore, GPs might prefer to address carers’ needs in separate consultations given most carers consulted the same GP as their index patient. 6

As expected, various patterns of communication emerged within the triad. The persons with dementia may have had difficulties making decisions about their own care due to disabling dementia communication patterns within the triad. 31 Both carers and GPs could have limited patients’ expression of their thoughts and wishes on several occasions; the former, by interrupting and speaking on behalf of them; the latter, by downplaying their concerns and colluding with carers. 23 On the other hand, carers facilitated GPs’ assessments of patients’ activities of daily living and safety issues; and facilitated information exchange between the specialists and the GPs, in the absence of truly integrated care.

Notably, throughout the consultations there were almost no references to nurses, psychologists, or social workers, consistent with our findings interviewing patients, carers, and health professionals.14

Comparison with existing literature

Consistent with previous research, 7-8,38 GPs did not seem to provide enough information about dementia. Frequently, neither the patients nor the carers asked GPs directly for this information, nor did the GPs offer them the opportunity to do so; this may indicate that dementia is not a subject for discussion with the GP for both patient and carer. 6 Our study supports previous suggestions that BPSD assessment is suboptimal in primary care, 4-5 which may result from GPs having educational needs in this area that remain unmet. 38 Importantly, this may lead to poor patient health outcomes and a higher carer burden. 39

Our findings are also suggestive of ‘fragmented care’, affecting the GPs and both specialists and social services (e.g. home care, day centres). This is consistent with international experience40 and with a European study that revealed great problems in accessing social services in Portugal. 41 Previous research on the barriers to dementia management in primary care has been focused mostly on the GP factors, 9 but potential benefits of involving other professionals in dementia care provision have been recently identified. 42

Finally, our study identified a few disabling communication patterns within the triad consistent with a previous study involving Admiral Nurses (dementia-dedicated nurses in the UK). 23 This may reflect study findings in which triadic encounters are complex, and where the dementia process can impair communication. 20-22 However, it may also indicate a lack of training in general practice in regard to communicating with persons with dementia. 9-10

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use naturalistic data to examine triadic encounters in the presence of dementia in general practice. It did not rely on participants’ recall of consultation contents but on their direct analysis. The analysis was performed by two authors with experience in consultations with dementia dyads in primary care, and in clinical communication training, which could influence their reflexivity. The analytical framework, allowed for a combination of inductive and deductive analysis.

There were also some limitations. This was a qualitative exploration study in a Portuguese small sample, so results are not necessarily transferable to other settings; however, triads were recruited from different social backgrounds and geographical areas. The participants were aware they were being tape recorded at the time of data collection, which could have altered their behaviour in consultations by the Hawthorne effect (particularly the GPs, who could also have prepared themselves for better performance). However, recording consultations for research purposes does not seem to affect their content. 43

General practitioners deliver continuing care to their patients and this study reports findings from just one consultation with each triad; therefore, the quality of dementia care delivery may not be fully reflected in the study findings. Therefore, information on the median time since the last GP consultation was provided in order to add context to the findings.

Implications for research and/or practice

This exploratory study has suggested areas for the improvement of dementia care in general practice. Analysis of triadic consultations with persons with dementia might be useful in judging care quality: a larger study could yield different, and perhaps more typical findings, and strengthen their transferability.

Findings regarding triadic interactions raise interesting issues that call for more in-depth analyses and larger samples.

Further research focusing on interactions within these triads is needed to identify GPs’ needs in consultation training. These results would inform consultation training using scaffolding approaches. Another area for future research concerns the coordination of care, further exploring the perspectives of all the stakeholders involved. Finally, strategies that promote family carers’ independent assessments may also improve the quality of care.

Conclusion

Overall, the present situation in Portugal is one of cautious hope, because the process of implementing the regional dementia plans has begun.18 Our findings may contribute to a national reflection on the important role of GPs and primary care services in dementia care.

It is challenging for GPs to assess dementia among other conditions in the context of fragmented care and contribute to tackling the major challenges related to dementia. In the future, the analysis of triadic consultations may provide potential process measures for assessing the quality of clinical practice and inform consultation training in general practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank the persons with dementia, their carers, and general practitioners who participated in this study. Maria J. Marques, Teresa Maia, Vítor Ramos, Isabel Santos, and Gabriel Ivbijaro have been involved in other studies of the project ‘Dementia in primary care: the patient, the carer, and the doctor in the Medical Encounter’.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, CB, MGP, and SI; methodology, CB, MGP, and SI; formal analysis, CB, and AF; investigation, CB; writing-original draft preparation, CB, MGP, and SI; writing-review and editing, CB, MGP, SI, AF, and SD; supervision, SD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.