Background

The so-called ‘blue book’ of the Portuguese Association of General Practice and Family Medicine (APMGF) was published in 1990 and became the cornerstone for the development of primary healthcare (PHC) and general practice/family medicine in Portugal ever since. In 2005, the reform of PHC based on this book’s principles transformed this particular healthcare sector and introduced a ‘pay-for-performance’ (P4P) model.1-3 However, the initial transformative atmosphere gave way to the current feeling of an incomplete reform: a significant part of professionals are not integrated into the Family Health Units (USF), the current type of primary care unit model; and a great proportion of citizens lack access to a family doctor.

Within this context, the authors felt the urge to renew the fundamentals of the ‘Blue Book’ and to establish A new future for General Practice/Family Medicine in Portugal.

The family doctor is, in Portugal, the specialist of general practice and family medicine (MGF), the doctor of the person. In the Portuguese National Health Service (NHS), family doctors carry out their activity in PHC and provide Person-Centred care to a relatively stable group of individuals, the patients’ list preferably organized by families (a ‘family list’), throughout their different life stages. Their activity is centred on health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of chronic and acute illnesses, management of multi-morbidity, and biopsychosocial complexity. The relationship with the Person is an integral part of their work. 4-7

The family doctor is part of a multidisciplinary team, with other doctors, nurses, clinical secretaries, and other health professionals, integrated with the community and in articulation with other healthcare institutions. The initial implementation of PHC in Portugal created large, broader, health centers that provided all the primary healthcare in a predefined region and encompassed all other small community healthcare units. General and family medicine (GFM) has been recognized as a specialty in Portugal since 1982. This unique designation was proposed to include both Family Medicine and General Practice, terms adopted in other countries to refer to the medical specialty for PHC. 1-2,8-9

The Portuguese Association for General Practice and Family Medicine was formally created in 1983, by the pioneers of this medical discipline in Portugal. In 1981 specific training for the specialty was created. In 1990 a broader training program for ‘in-practice training’ was implemented and a great development of the PHC occurred. 1,9 In the final years of the ‘90s, an experimental approach to a P4P model was attempted. The initial good results led to a broader implementation of the model, and the inclusion of the P4P model in the reform of the PHC, which started in 2005. The reform had a bottom-up approach, in which incentives were given to the teams that would self-organize to achieve higher levels of quality of care. Such implementation led to the creation of three different types of health units with different payment schemes. The Personalized Health Care Units (UCSP) were the evolution of the former healthcare centers. The Model A Family Healthcare Units (USF) were intended to be an intermediate, transitional model, with similar demands, but without the individual remuneration incentive only attributed to professionals of Model B” USFs. 2,8 However, until 2023, the reform of the PHC had not yet been fully implemented and only 42% of the population was registered in Model B USF, a significant part (30%) was still in Model A and the UCSP covered the remaining population. The stagnation was clear, with progressive and marked degradation of working conditions in the NHS, which makes it increasingly less attractive for family doctors. The right to health is determined by the Portuguese Constitution and PHC is the foundation of the NHS. In the base of the PHC, the family doctors show a paradox: despite the largest ever number of specialists in GFM in the country, there have never been so many citizens without assignment to their family doctor. The inability to attract and retain more family doctors in the public sector is evident.

This is, therefore, a highly complex and challenging moment and a unique opportunity to reform the Portuguese health system and the National Health Service, clearly stating the centrality of PHC and family doctors.

Principles and values (core values)

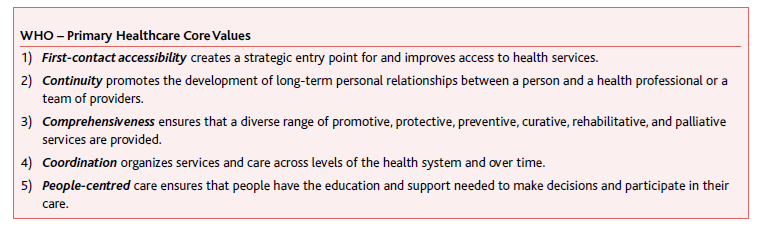

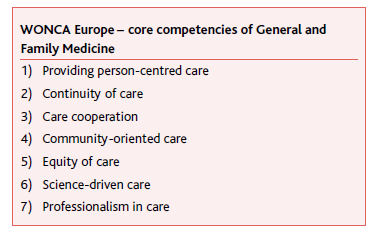

According to the WHO, “primary health care addresses the majority of a person’s health needs throughout their lifetime”. PHC should, therefore, be the basic healthcare offered by and to society as a whole to provide equity in access to healthcare and health. 10 Despite its evolution since the Alma Ata declaration in 1978, its principles still apply. 4 In Portugal, the APMGF adopts the principles and core values for PHC as defined by the WHO and the WONCA (Tables 1 and 2). 5

Fundamental activities in general and family medicine

Studies show that a solid network of GFM services is associated with better health outcomes for the population, lower mortality, and a decrease in avoidable hospitalization rates and hospital-care needs. 12 The relationship between family doctors and the people they serve is associated with fewer hospital visits and better quality of life. As such, the PHC should be the main entrance of the health system, where most health needs are met, and the key point in the coordination and articulation of care with other services within the system. 13-15

In Portugal, there is still no clear definition of which tasks are to be carried out exclusively by the family doctor or which can be performed by other professionals, such as physicians from other specialties, technicians and nurses, managers, or other professionals. We believe that the definition and/or the redistribution of some tasks would improve the quality of care provided and the efficiency and effectiveness of the health system as a whole. The latter would be important for freeing up family doctors to dedicate more time to what they are best qualified to do, particularly in areas such as surveillance of vulnerable groups (such as child health or maternal health), surveillance of patients with chronic diseases, acute illnesses, and preventive care.

In the context of PHC, family doctors are responsible for both the clinical management of the patient and of the multidisciplinary team. The definition and distribution of tasks among the various professionals and places of care - known as skill mix - seem to be essential to increase the quality of care in GFM, allowing a more efficient focus on tasks for which the family doctors are better prepared than any other professional. The activities that might be measured and evaluated in the context of the P4P scheme need to be aligned with the defined tasks for the family doctors and must be identified according to scientific evidence. Moreover, there should be an adjustment of the activities evaluated in each professional group.

The citizen’s path in the health system must be reviewed to ensure Person-centred care and functional inter-institutional coordination. The provision of care at the hospital level should be seen as a time-limited task within a continuum of care throughout the person’s life, tailored to their needs, with equal access guaranteed through referral by the family doctor. To accomplish this goal there is the need for a comprehensive dialogue between the Ministry of Health, other ministries, and the various players in the health system to place health in all policies and shape the system to people’s needs, reducing bureaucracy and tasks with low health value.

A great number of bureaucratic tasks - some of which are inadequate or unnecessary - are a significant portion of the family doctor’s daily work. In this context, specific measures need to be undertaken as necessary means to reduce workload. 16 Namely, it is essential to remove certification processes, that are not specifically related to the process of care and may cause conflict in the doctor-patient relationship. This could be accomplished by creating specific structures for this purpose (certification centers); namely those associated with ‘long-term’ certificates of short-term sick leave, medical certificates for driving licenses, registered athletes, or for school/kindergarten entry. Other bureaucratic duties that must be addressed include social security forms, prescription renewal for chronic medication or prescription for laboratory tests, and medical exams. Task simplification must also be implemented in unit administration, including not only internal processes but also external coordination with other levels of care.

Operational organization of PHC Units

It is possible to identify a set of barriers to access to health care concerning the scope of GFM, that can be grouped into five dimensions: proximity, financial effort, capacity, suitability, and acceptability. 17-18

Concerning the physical structure of PHC units, it is urgent to rethink the architecture and the structure of future proximity care units, namely through the creation of large spaces, without architectural barriers and accessibility for people with reduced mobility: humanized and community-oriented spaces. All PHC units must be well equipped and with sufficient workspaces, including multipurpose workspaces. Buildings must be constructed considering the circulation of people and their future needs, as well as a predefined maintenance plan for all infrastructure, materials, and equipment.

The organizational structure of PHC units must be addressed comprehensively, considering all aspects of daily activity (for professionals and patients) and time expenditure. The patient circuit must be improved by the reduction of contact points and optimization of contact time with the unit. The use of technologies may bolster administrative simplification through automatic services in the digitalization of admission or standardized communication through telephone and digital channels with artificial intelligence (AI), for example. Multidisciplinary actions and teamwork are fundamental characteristics of the performance of a family doctor. Promoting a healthy work environment is essential not only to attract and satisfy professionals but also to ensure greater productivity and longevity at work. The health and well-being of all people who live and work in the healthcare system should be a priority for management. It is crucial to understand the different needs, expectations, and experiences of human resources, ensuring inclusion and a sense of belonging and promoting support and continuous development of all professionals. 19

The health system should incorporate digital solutions, make the best use of technology, and facilitate new ways of working, planning, and providing healthcare, especially considering new needs. It is important to dematerialize most documents, ensuring remote access to electronic health record (EHR), which could also serve to extract medical reports and certifications autonomously, considering standard protocols. 20-22 In this regard, it is essential to have a true high-quality unified health record (based on the full implementation of an effective EHR), that collects, in a single place, all the clinical information of any citizen, throughout their life cycle. 23-24 This EHR should enable information sharing between different levels of care and health providers, covering the NHS, contracted services, and the private and social sectors. Effective cooperation and coordination between different levels of care is highly necessary to ensure continuity and integration of care in primary, outpatient, home care, hospital, and social security institutions. A truly integrated single HER must permit differentiated access levels, information sharing by all providers, and a common denominator in the provision of care, under each care plan. The latter may be of great value to gathering information, automating report extraction, and being the base for referral to and from different healthcare levels or institutions. Furthermore, a centralized registry must allow access to a statistical module, with automatic monitoring indicators, that should facilitate clinical audits, stimulate research, and contribute to the reflection about clinical practice towards quality improvement.

To achieve this goal, it is necessary to establish common policies for the process of care. This needs to be articulated between different ministries, the public sector, and the social sector for a transparent and well-defined communication and articulation protocol. Attributions and responsibilities need to be established, along with a systematized circuit and a shared plan of care for every individual.

Human resources in general and family medicine

The revision and update of the salary grid are essential for the recruitment and attractivity of GFM careers: attributing fair remuneration to the effective medical responsibility and adapting it to the current cost of living along with the revitalization of the medical careers, consistent with a real and achievable professional progression. Moreover, other measures should include the flexibility of the work contract, with fair compensation for non-clinical activities (such as research and project leadership for example) and the adjustment of the workload based on the adequacy of the patients’ list size. 16,19

Beyond the remuneration aspects, measures like the facilitation of work-family balance and ensuring feasible workload and fluid workflow may contribute to this objective. Therefore, it is important to increase the flexibility of working hours and contracts, to review the number of patients in the family doctor patients’ lists, and to reduce bureaucratic procedures by increasing the real autonomy of teams and the modernization of information systems. 16,25 Other measures may include hiring all necessary human resources, involving other PHC professionals, and the acquisition or renovation of adequate facilities and essential equipment. Furthermore, there must be adequate remuneration for holding positions of responsibility: training supervisors, auditors, members of the technical council, coordinators, and clinical directors, among others.

In 2017, the APMGF published a work entitled ‘A new metric for the patients’ list: ensuring quality, adjusting the quantity’, which contains proposals for measuring, comparing, and resizing the family doctor patients’ lists. For the first time, this paper proposed a global indicator that allowed the adjustment of the size of patients’ lists to different clinical contexts of exercise on a national scale. Amongst other aspects, it developed the concept of weighted and adjusted units to adjust the size of patients’ lists to the complexity of local constraints. 26 The introduction of such a metric contributes to the creation of conditions to encourage the creation of new PHC units in places where current conditions are unfavorable. Moreover, it would make it possible to adjust the workload of a patient’s list with other non-clinical activities of public interest developed by family doctors.

The flexibilization of work is a demand of the present, crucial to maintaining work-family balance and the expected quality of life for the family doctors. The possibility to choose the reduction of workload should be carried out, in a free and flexible way, with due adjustment of remuneration and the size of the patients’ list. Other possible measures may include flexible working hours, reduction of basic working hours; providing sufficient time dedicated to list management and clinical governance, the possibility of teleworking, combining clinical activity with protected time for training, research, teaching, and management activities, with the proportional adjustment of the size of the patients’ list and fair compensation. 21,25

Professional career progression is a matter of critical importance. The revitalization of the medical career, with the professional progression of physicians based on well-defined technical and scientific skills is vital for continuous improvement, training, and professional development. The process must be flexible, transparent, rigorous in its application, and adequate to the specific functions of GFM. The introduction of certification and recertification processes may be important to ensure that the provision of care meets high-quality standards, following the advances in GFM and the health needs of the community.

Family doctors are frequently assigned to other missions besides direct medical assistance. These activities are frequently considered a reward or a promotion as a recognition for good work and demonstrated skills. However, for many of these roles, the compensation is poor or even nonexistent. Moreover, these activities are frequently not adequately valued by peers or the work team, and many times represent after-hours work, despite their relevance for the system. It is of great importance to value other activities in GFM parallel to clinical practice. It is crucial to ensure the conditions for family doctors to carry out other non-assistance professional activities, such as management, teaching, and research, amongst others, without any form of penalization in terms of medical careers or remuneration, as in the P4P model.

Pay for performance

In the context of a modern P4P model suited to the activity of family doctors, APMGF stands for a simplified and fair system that rewards quality over quantity, measured in terms of people’s health gains.

A new compensation model to reward performance in medical activity should:

Prioritize value in health;

Be person-centred instead of disease-centred (e.g., the HbA1c value);

Reduce assistance inefficiencies (such as duplication of care).

The awarded incentives must focus on the continuous improvement of the quality of care on the premise of value-based healthcare. The health units should “stop doing what is unnecessary to be able to do what is essential”, avoiding, for example, the duplication of care (between health professionals in the team and between sectors in the healthcare system).

The assessment of the work of family doctors should consider the fundamental characteristics of GFM and focus on health outcomes, accessibility, and satisfaction. The metrics used for evaluation should be, as far as possible, independent of the professional’s direct action to register/achieve them. The global reorganization of PHC requires a real unified health record that is person-centred and encompasses its integrated path through the health system.

The performance Indicators used to measure the professionals’ activity are pivotal for every P4P model. The indicators must be supported by robust evidence, with a weighed assessment of health gains and value. There should be an increase in the number of outcome indicators and fewer process indicators, ensuring a balance between simple, direct, and easily comprehensible indicators, with more complex/comprehensive ones that are, therefore, less subject to possible biases and distortions. Ideally, they should not be user-dependent. 27-29

Such reorganization requires a performance-sensitive universal remuneration model, without the need to differentiate typologies of services, that reflect the quality in its comprehensive dimensions, the quantity of care, and the equity between providers.

Conditions for general and family medicine with Quality - The Future

Clinical governance as the framework through which healthcare organizations are accountable for continuously safeguarding high-quality of care is an essential mechanism for quality improvement. Health governance strategies should be oriented toward producing health outcomes or consequences in the context of efficiency, quality, and clinical safety. 7,30 The latter should be decentralized, participatory, and based on principles of rationality and efficiency (reducing costs and resources required to execute them).

The implementation of such a system advocates for five dimensions: recording, comparison, reward, continuous improvement, and partnership.

For recording activity, the doctor should have access to a unified, integrated, intelligent, and user-friendly platform that allows up-to-date records of all important information about the individual. All information should be available to all teams transparently, enabling comparison and benchmarking. The installation of intelligent systems, periodic monitoring, and regular pedagogical audits are possible tools for continuous quality improvement for all healthcare units. 24 This allows for automatic monitoring of processes with effective accountability concerning the results obtained. A strategy to consider involves compensating professionals and their teams for improvement relative to the initial value. The proposed governance process relies on a logical strategy for quality improvement in continuous cycles of collective inter-team learning, training, and investment in research as a driver of improvement.

Ensuring accessibility fundamentally relies on adequately sizing patients’ lists and the prediction of their health needs. It also involves ensuring that different access routes to the family doctors are equitably manageable. Low health literacy significantly impacts the overutilization of healthcare services. Enabling and empowering patients, giving them the ability to understand and cope with life and illness and gain of control and responsibility over their healthcare decisions is an important aid in improving resource distribution, with gains for the people’s health. This is not a task exclusively within the medical sphere or healthcare services but for all society.

Teleconsultation and email played a significant role during mandatory lockdowns and will continue to have a role when another alternative is not feasible. The issue of data security is central, so only platforms that demonstrate compliance with this requirement should be used. New technologies should be seen as tools that enhance communication, work, and information management, freeing doctors for relationships and care. It will be essential that all forms of communication function in articulation with the applications used in each of the units and with the professionals’ schedules. 16,31-33

On the other hand, artificial intelligence can be useful in the context of consultations to support the decision-making process, with decision algorithms embedded in the system supporting diagnosis, treatment, and guidance. It can also be used for automatic coding, supporting the need for consultation, and potentially in self-care and compliance with guidelines. 20,22 Technological development should be accompanied by more effective management of human resources, especially healthcare professionals, as new forms of access require a reorganization of time and continuous training. It is crucial to invest in human resources, developing them in governance processes, empowering them in technical-scientific areas, multitasking, with organizational flexibility, making them able to face the change where efforts and health gains are effectively rewarded.

A new unit model - The Quality System

There is a need to simplify the current quality system and the incentives scheme to fairly value work and attract available professionals. The established objectives should preferably include outcome metrics with proven impact on people’s health. 29

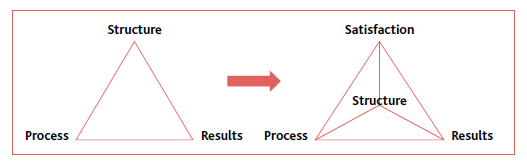

APMGF proposes the implementation of a novel and unique quality system based on a comprehensive, simple, and intuitive information system that incorporates the documentation of the units and is based on the classic Donabedian triad: “structure, process, and results”. 34 This system will be, simultaneously, the governance and the evaluation platform. The quality system considers two dimensions that should be aligned: 1) the satisfaction of the person in terms of valuing the results in health that matter, and not the mere satisfaction with the ‘services provided’; 2) the satisfaction of professionals with the care they provide, and the health outcomes achieved by the people they care for. Fig. 1

Figure 1 Evolution of the classic quality triad to a three-dimensional quality structure that considers satisfaction into account (workers and clients).

The information system needs substantial improvement, particularly to enhance its capacity and potential to contribute to organizational development. This includes the establishment of a computerized platform for each unit that encompasses all unit documentation, both public and confidential. This governance platform should generate team evaluations, impacting the remuneration incentives for the units. The evaluation of units would be carried out interactively and in real-time through the quality system platform in the components of Structure, Process, and Results, with a minimum threshold established for goal attainment to allocate incentives to team professionals. However, the existence of annual improvements should be valued. The assessment of satisfaction (professionals and patients) should not have a direct impact on the remuneration valuation of professionals but rather contribute to the continuous improvement of the team and the assessment of organizational risks and professionals’ well-being.

Based on this model, in addition to basic incentives for institutional improvement, we propose that the remuneration regime for GFM specialists should consist of three components: 1) base salary, corresponding to the basic salary for the respective level of the medical career; 2) individual compensation, based on the performance of each family doctor according with the achievement of defined objectives; and 3) team compensation, dependent on the valuation of the quality system, based on the value in health and the activity of the team, being attributed, proportionally, to all of its elements.

Management structures would have the role of supporting the units to achieve their objectives and help them to meet their needs, rather than negotiating thresholds. In this model they will also be responsible for providing the resources to, flexibly, meet recurring unpredictable needs for human resources, ensuring the agility and effectiveness of the replacement necessary to prevent the overload of the other professionals of the team.

The individual performance compensation should be paid independently of the team’s incentives. Its achievement should fairly value the activity of the physician. The valuation of the latter should include the achievement of objectives, components related to context, and the total number of people to whom care was provided. In this way, the obtained result would then be weighted by a capitation multiplier (a continuous value where the number 1 corresponds to the ‘base’ list size and increases proportionally with the addition of people to the list), as well as a ‘complexity multiplier’ (a value calculated based on the characteristics of the patients’ list and the context of care provision).

In summary, the calculation of individual incentives to be awarded is based on professionals’ performance, which depends on the objectives, the number of patients, and their complexity.

Other tasks and responsibilities undertaken by the doctors should be compensated with remuneration equivalent to the proportion of the incentive for an equivalent period of work (e.g., hours allocated to functions such as PCC, research, ICPCJ) or by assigning a fixed amount related to specific responsibilities in the unit, such as coordination or technical advice. The variable salary component to be assigned to team members, according to the quality system evaluation, should reward professionals for the increased organizational quality and care provision implemented, particularly in continuous improvement processes, teamwork, and citizen centrality.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, GC, NJ, AR, AP, PB, SS, NM, CO, DV, MS, AMC, CF, CM, CJ, JRT, IR, and VS; methodology, GC, NJ, AR, AP, PB, SS, NM, CO, DV, MS, AMC, CF, CM, CJ, JRT, IR, and VS; validation, GC, NJ, AR, AP, PB, SS, NM, CO, DV, MS, AMC, CF, CM, CJ, JRT, IR, and VS; investigation, GC, NJ, AR, AP, PB, SS, NM, CO, DV, MS, AMC, CF, CM, CJ, JRT, IR, and VS; writing - original draft, GC, NJ, AR, AP, PB, SS, NM, CO, DV, MS, AMC, CF, CM, CJ, JRT, IR, and VS; writing - review & editing, GC, NJ, AR, AP, PB, SS, NM, CO, DV, MS, AMC, CF, CM, CJ, JRT, IR, and VS.