Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies no.7 Faro dez. 2011

Determinants for tourism and poverty alleviation

Determinantes para a Redução da Pobreza Através do Turismo

Susana Lima1; Celeste Eusébio2 and Maria do Rosário Partidário3

1Lecturer, ESEC, Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra , GOVCOPP, DEGEI, University of Aveiro sulima@esec.pt

2PhD, Assistant Professor, GOVCOPP, DEGEI, University of Aveiro celeste.eusebio@ua.pt

3PhD, Associate Professor, IST, Technical University of Lisbon mrp@civil.ist.utl.pt

ABSTRACT

In the last decade, commitment to tourism as a development strategy for the developing world has gained a renewed interest by governments and development organizations in the fulfillment of the Millennium Development Goals. This was established as a major priority by donors, governments, NGOs, national and international tourism bodies, bilateral and multilateral institutions, like the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). The purpose of this paper is to identify the main determinants that should be integrated in the international cooperation for development programs that use tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation. By way of a case study it is analyzed the role played by the UNWTO.Volunteers Program in this context examining if it integrates the determinants previously identified in the literature review. To accomplish the research objectives, data collection included: documental analysis, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews with UNWTO participants. While no evidences exist yet due to the recent implementation of the UNWTO.Volunteers, the findings suggest that if these programs manage to have a positive influence on all, or at least in some of the dimensions, then it is possible that it responds to some of the main determinants for poverty alleviation in order to reinforce the local communities capacity-building.

KEYWORDS: Tourism, Poverty Alleviation, International Cooperation for Development, UNWTO. Volunteers Program.

RESUMO

Na última década, verificou-se um crescente interesse pelo turismo como estratégia de desenvolvimento no compromisso assumido com os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento do Milénio. De facto, esta estratégia foi definida como uma prioridade por doadores, governos, ONGs, administrações nacionais e internacionais de turismo e instituições bilaterais e multilaterais, como é o caso da Organização Mundial de Turismo. O objetivo deste artigo é identificar as principais determinantes que deveriam ser integradas nos programas de cooperação internacional para o desenvolvimento e que assumem o turismo como instrumento de redução da pobreza. Através de um estudo de caso, é analisado o papel desempenhado pelo Programa UNWTO.Volunteers neste contexto, verificando até que ponto as determinantes identificadas na revisão da literatura são integradas. Para atingir os objetivos da investigação, a recolha de dados assentou na análise documental, observação participante e entrevistas semi-estruturadas a participantes no programa em análise. Apesar de não ser possível ainda encontrar evidências sobre os resultados do programa, devido à sua recente implementação, os resultados da investigação apontam para a importância de integrar aquelas determinantes, se não na totalidade, pelo menos parcialmente, no sentido de contribuir para a redução da pobreza nos destinos objeto de intervenção, pelo reforço da capacidade das comunidades locais em assumirem o seu próprio desenvolvimento.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:Turismo, Redução da pobreza, Cooperação Internacional para o Desenvolvimento, Programa UNWTO.Volunteers.

1. INTRODUCTION

Poverty eradication is the first of the United Nations established Millennium Development Goals (MDG), with sustainable tourism being recognized as a major development activity to the attainment of this goal. Over the last years, commitment to tourism as a development strategy for the developing world has gained a renewed interest within governments and development organizations in the fulfillment of the United Nations MDGs. However, despite several developing plans, aid projects, grants, loans and structural adjustments, limited progress has been made to achieve the targets defined in that goal (Lima et al., 2011).

Poverty is a multidimensional and complex concept that cannot be reduced to a single dimension of human life. Poverty includes inadequate income and human development, but also embraces deprivation of a longer life span, access to safe water, lack of health, acceptable housing, knowledge, creative life, freedom, voice, participation, dignity, self-esteem, power, representation, personal security and respect of others (Zhao and Ritchie, 2007; Sharpley and Naidoo, 2010).

Several approaches to international development assistance emerged in the recent decades in which tourism is considered the main tool for poverty alleviation. Nevertheless, a gap is evident in the scientific literature as little emphasis has been given to the impact of tourism on poverty alleviation through international development cooperation programs.

Considering that the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) is the leading international organization with a decisive and central role in the world tourism and on the ability to influence national and international development policies, it was considered relevant to analyze its role in the overall discussion around the international cooperation for development in tourism. This is even more required since it achieved the status of a UN specialized agency, having tourism since then gained official acknowledgement from the World Bank on its importance for poverty reduction, according to the MDGs. In the last decade, the UNWTO reinforced its efforts to promote sustainable tourism development in order to reduce poverty. It launched several initiatives and programs assuming a leading position to promote tourism as a potential tool for development, in line with the MDGs. This is the case of the Sustainable Tourism for Eliminating Poverty (STEP) and UNWTO.Volunteers programs, yet with different focus.

The former was launched in 2002 to develop sustainable tourism as an engine for poverty alleviation, in line with the principles of the pro-poor tourism initiative. It targets mainly the world’s poorest countries, with a major focus in Africa, and comprises mainly projects at a very local level. The UNWTO.Volunteers Program, in turn, has different characteristics being more focused on a knowledge transfer perspective. This program is presented in more detail as the object of a critical analysis based on the case study presented further ahead in this paper.

In line with the above, this paper is set with a twofold purpose: first, to identify the main determinants that should be integrated in the tourism international development cooperation programs when poverty alleviation is the main aim; and second, by way of a case study, to analyze the role played by the UNWTO.Volunteers Program in this context examining if it integrates the determinants previously identified. The paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the methodology used to conduct the research. It is ensued by a literature review about tourism, poverty alleviation and international cooperation for development. The following section presents the UNWTO.Volunteers Program as a case study, describing the program and its application to the Mexican state of Chiapas in 2008. A critical reflection about the UNWTO.Volunteers Program is provided in this section discussing each of the determinants for poverty alleviation identified in the literature review. This is done in order to understand the possible impacts of this program on poverty alleviation, in the specific case of Chiapas. The paper concludes with reflections on the theoretical and practical implications for future research and highlights concerns that need to be addressed in the discussion about tourism, poverty alleviation and international cooperation for development.

2. METHODOLOGY

Two key phases were involved in this research. The first phase sought to identify the main determinants to consider when poverty alleviation is the main aim under the tourism international development cooperation programs. This was done through a process that included the review of contemporary development studies and practices about tourism and poverty alleviation.

The second phase was concerned with the applicability and its discussion on the determinants of poverty alleviation in the context of a development intervention as identified in the first phase of the research. This was done in light of a case study based on the UNWTO.Volunteers Program.

The justifications for using a case study as a research strategy are well documented (Creswell, 1998; Yin, 2003). It was selected specifically the UNWTO.Volunteers Program undertaken in the Mexican state of Chiapas for two main reasons. First, the UNWTO.Volunteers Program constitutes an approach that aims to support developing countries to achieve a sustainable and more competitive tourism sector based on a knowledge sharing process between the local stakeholders, specialized international volunteers and local experts. This is considered a distinguishable approach comparing to other international development cooperation programs and with a potential to accomplish some of the main determinants identified in the first phase of the research. Second, being a volunteer of the UNWTO.Volunteers Program, the first author had the opportunity to have an active participation in the implementation of this program in Mexico in 2008.

To achieve the research objectives, data collection included three techniques: documental analysis, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews with UNWTO participants.

Documental analysis was based on several UNWTO data and reports related to the mentioned program conception and implementation. This was facilitated by the participation of the first author in an intensive UNWTO.Volunteers course that is a precondition to belong to its volunteers´ team. In this phase it was possible to learn all about the aims and phases conceptualized for the program. This was complemented by the participation in its implementation in Mexico that resulted from the respective selection process. Therefore, participant observation was carried out during the three weeks of the field work, in September and October of 2008. This allowed for the researcher to immerse herself in the social setting under study, getting to know the key actors in the process with whom it was possible to establish informal conversations and interaction. This personal experience gave a deep understanding of the context in which this program is developed and the dimensions that are more important to work with. Objective notes were taken in a field notebook which was crucial for the research. At last, in order to complement the researcher view of the program implementation in this exploratory phase, semi-structured interviews to UNWTO volunteers and experts were conducted. This took place in the last days of the fieldwork and was intended to cover all the eleven international volunteers, three local volunteers, and UNWTO experts. Nevertheless, mainly due to time constrains it was only possible to interview seven volunteers and one expert. The main aspects covered by the interviews included the expectations towards the impact of the program on the region’s development, the methodology used to collect and discuss data, as well as the role played by the program in terms of its potential to reinforce community capacity building.

3. LITERATURE REVIEW

From the review of contemporary development studies and practices it was possible to identify as the major determinants for tourism to contribute to poverty alleviation the following: community participation (Brohman 1996; Chok et al., 2007; Cole, 2006; Tosun, 2000); ownership and leadership (Brohman, 1996; Cole, 2006; Scheyvens, 2007; Tosun, 2000; OCDE, 2005); opportunity in commercial viability and access to markets (Alsop and Heinsop, 2005; Harrison, 2008; Zhao and Ritchie, 2007); empowerment (Cole, 2006; Eade 1997; Scheyvens, 2007; Sofield, 2003; Zhao and Ritchie, 2007; Schilcher, 2007); access to information, knowledge and communication (Cole, 2006; Nadkarni, 2008; Romanow and Schilcher 2007; Sheate and Partidário, 2010; Tosun, 2000; White, 2004); networking (Cooper, 2006; Novelli et al. 2006; Shaw and Williams, 2009); safety and security (Hall and Brown, 2006; Zhao and Ritchie, 2007); focus on equity (Harrison, 2008; Schilcher, 2007); and governance (Brohman, 1996; Clancy, 1999; Dinica, 2009; Fritz and Menocal, 2007; Grindle, 2007; Harrison, 2008; Scheyvens, 2007; Schilcher, 2007).

Community participation is essential in development as it results in more suitable decisions (Cole, 2006). As a service industry, tourism is highly dependent on the goodwill and cooperation of host communities. Tosun (2000) further argues that the local community is more likely to know what will work and what will not in local conditions.

Several developing countries face the problem of ownership and control being confined mainly to foreign chains and large-scale national businesses, particularly within the hotel industry. This means that only multi-national companies and large-scale national capital reap most of benefits associated with the industry leading to higher leakages (Cole, 2006; Scheyvens, 2007; Tosun, 2000). The dimension of ownership should also consider the perspective of the agreements under the "Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness" which defends that any project for development cooperation should focus on national ownership where partner countries commit to "exercise leadership in developing and implementing their national development strategies" and donors "respect partner country leadership and help strengthen their capacity to exercise it" (OCDE, 2005, p.14).

Zhao and Ritchie (2007) propose an integrative framework for anti-poverty tourism research, arguing that any development effort or approach, to be justified and successful, should consider three main determinants: opportunity, empowerment and security.

Opportunity means the poor ought to have access to economic opportunity of which they can take advantage to change their destiny (Zhao and Ritchie, 2007).

In the context of the development work, empowerment is a key word although it may be subject to different interpretations. The definition of Eade (1997: 4) correspond to a consensual idea of a process of "gaining the strength, confidence and vision to work for positive changes in [women, man, and children’s] lives, individually and together with others". She further argues that "women and men become empowered by their own efforts, not by what others do for them", and therefore "when development programs are not firmly based on people’s own efforts to work for change, their impact may be disempowering". Scheyvens (2007) emphasizes it as the importance of local communities having a high degree of control over the tourist activities taking place in their area, and sharing the benefits. For this to occur it is often necessary for states to intervene to provide appropriate legislation and support in the way of information and training (Scheyvens, 2007).

While knowledge is a crucial element of empowerment (Tosun 2000), communities need access to a wide range of information. Furthermore, "meaningful participation cannot take place before a community understands what they are to make decisions about" (Cole 2006, p.632). In fact, as pointed out by Ashley et al. (2001), the poor have a weak understanding about tourists as well as the way the tourism industry works, and changing this state of affairs would be very important to make informed and suitable decisions about their own tourism development. A knowledge deficit perpetuates a vicious cycle of economic deprivation and poverty (Nadkarni, 2008).

Communication is then a central dimension for capacity building as it is a condition for knowledge sharing that in turn leads to empowerment. In fact, communication lies at the basis of all human development, in any context (Romanow and Bruce, 2006). Current theories of communication for development consider the lack of political, economic and cultural power of lower-status sectors as the major problem to be tackled in development (White, 2004). The majority do not have access to the education, technical assistance, good health and housing needed to make a contribution to development. Therefore, capacity building has to take place in the context of communication practices and processes. The most important thing communities can do to build capacity is to engage in multidirectional dialogue with all community stakeholders (Romanow and Bruce, 2006).

Where stakeholder engagement needs to be focused, it is crucial to generate strategic competitive advantage through networks (Cooper, 2006) which, associated with clusters of interests, are preconditions for innovation and community capacity building (Dredge, 2006). Nonetheless, many organizations and stakeholders need to be persuaded that cooperation will enhance their own competitiveness, and thus there is a need for demonstrating the benefits of cooperation across the destination (Cooper, 2006; Dredge, 2006; Shaw and Williams, 2009). Networking, clustering and agglomeration theories are increasingly being adopted to explain the role of tourism in influencing local growth and stimulating regional development as reviewed by Novelli et al. (2006).

Safety and Security refers to the reduction of the vulnerability of the poor to various risks such as ill health, economic shocks and natural disasters. Therefore, a social security system, specifically for the poor (Zhao and Ritchie, 2007), and safety nets, considered one of the key capabilities for good governance (DFID, 1999), would be required.

Concerning Equity, there should be a focus on redistribution, which entail closer attention to the role of the State (Brohman 1996; Clancy 1999; Harrison 2008) as well as to the wider world system "so that developing countries are granted greater decision-making power in institutions such as the World

Trade Organization" (Schilcher 2007: 182). Promoting tourism per se as a tool for poverty alleviation constitutes a neo-liberal pro-poor approach that neglects the dimension of equity, which may lead to an aggravation of poverty (Schilcher 2007: 167). To be sustainable, the processes of change induced by any development intervention must promote equity between, and for, all women and men (Eade, 1997).

The role of the State is crucial. There is a general agreement that "better and more effective states are needed if development is to succeed in the world’s poorest countries" (Fritz and Menocal, 2007: 532).

Without genuine government intervention the poorest are bound to carry a heavier burden in terms of costs of environmental degradation, cultural commodification and social displacement. Moreover, "it is often necessary for states to intervene to provide appropriate legislation (...) and support in the way of information and training" (Scheyvens 2007: .241). Institutional development and public involvement, but also transparency in decision making, interest representation, conflict resolution, limits of authority, and leadership accountability are all issues of governance (Grindle, 2007).

Governance is a critical issue in moving development towards sustainability. Its concept is complex and there is a wide variation in the manner in which development agencies, international organizations and academic institutions view its meaning. UNDP (2000: 1) definition of democratic governance focus on the essential role it plays for achieving the MDGs, considering it as "the system of values, policies and institutions by which a society manages its economic, political and social affairs through interactions within and among the state, civil society and private sector". Given the broad existing definitions, Grindle (2007: 555) states that "it is often not clear how governance can be distinguished from development itself".

As far as tourism governance structure is concerned, there are several actors to be considered, which have impacts on the sustainability performance of the sector: public authorities at all governmental levels, domestic and foreign private sector agents, tourists and local communities (Dinica 2009) and the civil society.

It is worth to note that the determinants of poverty alleviation are all interconnected. This means that any development effort to be effective should work on the set of determinants considered more important in the context of the intervention, and on the inherent mutual relationships in order to reinforce capacity building. In fact, capacity building combines the major determinants discussed above when tourism is to work as a tool for sustainable development contributing to poverty alleviation in developing countries.

Capacity building is, therefore, considered in this research in its wider context, as presented by Partidário and Wilson (2009), who state that it is a concept founded on sound principles of democracy, participation, development and continuous improvement of skills, shared learning processes and equal access to opportunities. The re-emergence of the debate on sustainable development, preceding and following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, in 1992, has placed capacity building at the top of priorities for international development assistance, as a condition to enable the achievement of effective and sound development in all regions of the world. Currently it is recognized that capacity building is not only about international development assistance, but it is about ensuring technical and decision capacities in all countries and regions, that will lead to new ways for making better decisions that ensure that environment and social issues are integral parts of economic development.

Therefore all efforts to break away the vicious circle of poverty through tourism as a tool to convert it into a virtuous circle should focus on the ways and means to reinforce the capacity building of local communities in all its dimensions. If the programs manage to have a positive influence on all, or at least in some of the dimensions, then it is possible that capacity building becomes reinforced contributing to the foremost goal that is poverty alleviation.

4. CASE STUDY: THE UNWTO.VOLUNTEERS PROGRAMME AND POVERTY ALLEVIATION

4.1. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE UNWTO.VOLUNTEERS PROGRAMME

In 2007, UNWTO put into practice the UNWTO.TedQual Volunteers Program – which was renamed latter as UNWTO.Volunteers Programme, through the UNWTO.Themis Foundation. This program was designed to support developing countries to accomplish a sustainable and more competitive tourism sector based on a knowledge management framework through education, training and research (UNWTO, 2009).

Knowledge sharing and transfer are the main focus of this program which is further supported by volunteer participants from universities and other education institutions in the developed and developing worlds as well as governments and civil society in the countries which host the program.

The main aims of the UNWTO.Volunteers Program are the following (UNWTO, 2009):

* To train, in both theory and practice, volunteer professionals with the suitable vocation and skills in the field of tourism as an instrument for development;

* To support the UNWTO Member States and international cooperation agencies in the formulation and implementation of plans and programs through the technical contribution of UNWTO experts and volunteers;

* To disseminate, through education and training, the policies of the UNWTO in the field of tourism, especially, tourism's role as an instrument of development and its potential to contribute to poverty reduction;

* To promote the spirit of service and solidarity rooted in the essence of volunteerism.

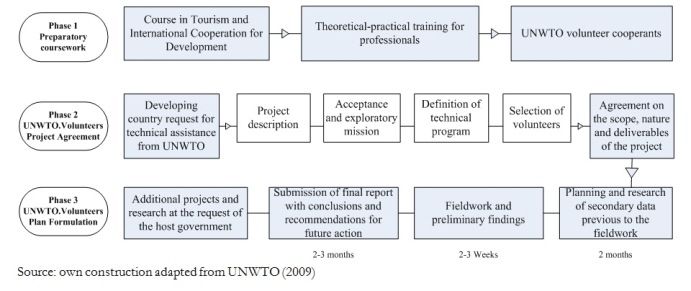

To achieve these purposes, UNWTO.Volunteers Program is structured as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: UNWTO. Volunteers Structure

The first phase of the UNWTO.Volunteers Program is concerned with the training of young professionals with vocation and skills in tourism as an instrument for development assistance. This is provided through the completion of a blended (online and classroom-based) "Course in Tourism and International Cooperation for Development", organized by UNWTO.Themis Foundation.

UNWTO.Volunteers Program undertakes a tourism development project in a region or destination in a developing country that asks for support to UNWTO to develop a project considered important for its sustainable tourism development efforts (Phase 2). This request should include a project description, which specifies the country and region, the counterparts, the local technical team, as well as the assigned areas which may include: marketing strategies; product assessment and identification of product gaps and product development; business plan creation; international development; and development of community-based tourism plans (Ruhanen et al., 2008; UNWTO, 2009). After an exploratory mission by UNWTO experts and staff to the host country, and the definition of a technical program, UNWTO and the host country government agree on the scope, nature and deliverables of the project.

The program will be undertaken then in collaboration with local stakeholders and the selected volunteer group and UNWTO experts, through the following steps (Phase 3): planning and research of secondary data previous to the fieldwork (2 months); fieldwork and preliminary findings (2-3 weeks); submission of final report with conclusions and recommendations for future action (2-3 months).

The volunteer participants will be involved for about six months in the project. During this period they will work on extensive research on tourism in the selected country including an analysis of general tourism trends for both the destination and the broader region, "including visitor arrivals data and traveler profiles, competitive benchmark analysis and assessments of current branding, image and marketing strategies" (Ruhanen et al., 2008: 29)

The intended knowledge management approach to volunteering implies the cumulative knowledge and expertise of the UNWTO being transferred to governments, tourism organizations, and civil society in the developing countries in order to to increase the country’s knowledge capacity, and thus assisting their sustainable development efforts (Ruhanen et al., 2008). Since 2007 and until 2010, the projects took place in the following destinations: Mexico (Chiapas, 2008), Uruguay (2008), Colombia (2009), and Brazil (2010).

4.2. THE UNWTO.VOLUNTEERS PROGRAMME IN CHIAPAS, MEXICO

In 2008, the UNWTO.Volunteers Program undertook a project in Mexico to develop a competitiveness plan for five municipalities of the state of Chiapas, and a tourism vision for the year 2015. This was organized by the Government of Mexico, the Government of the state of Chiapas and the UNWTO, and involved five municipalities.

In order to achieve the project purposes, in October of 2007 an exploratory mission was undertaken comprising fieldwork visits from the UNWTO officials to the five municipalities. This included some interviews with the official authorities from the state, municipalities and also the private sector. In August of 2008 an Agreement was signed for the formalization of the project named "Chiapas 2015", with the participation of the local official authorities and the UNWTO officials.

With the agreement on the scope, nature and deliverables of the project, it was decided that the technical program should integrate the following elements:

- Diagnostic of the present situation of the local tourism system;

- Development Model proposal;

- Specific programs of action.

To undertake this project, it was selected an interdisciplinary team of eleven international volunteers from Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Guatemala and Mexico, all of which previously completed the UNWTO.Volunteers coursework program of the 2007 or 2008 editions. Additionally, three local volunteers were integrated in the team plus three UNWTO experts and officials.

To accomplish the defined technical program, the volunteer team was divided into three groups, to work online from its respective countries of origin, following a plan set off by the UNWTO experts for the project, relative to the research of secondary data about the tourism destination. Subsequently, the 3-week fieldwork trip took place in September and October of 2008, with the guidance of the officials from the tourism administration of Chiapas.

The volunteers undertook interviews, workshops, surveys and an inventory and analysis of the tourism resources. Consultation and engagement of the local community in the project was a primary consideration and during the fieldwork hundreds of people were consulted in interviews and workshops with representatives from municipal and state governments, the private sector and civil society.

In April 2009, the UNWTO delivered to the authorities of Chiapas the report "Chiapas 2015: Strategic Planning and Tourism Competitiveness", consisting of a development plan for tourism competitiveness, including the strategic development proposals for the 5 municipalities involved.

4.3. POVERTY ALLEVIATION DETERMINANTS IN LIGHT OF THE UNWTO.VOLUNTEERS PROGRAMME

So far the UNWTO.Volunteers Program shows no evidences on the effective impacts on poverty alleviation due to its recent implementation. However, it presents a considerable potential to give an innovative contribute to international development assistance for tourism in developing countries, as it looks to respond to some of the main determinants of poverty alleviation. The set of determinants considered as the basis to achieve capacity-building should be adapted to the different contexts of intervention within international development assistance. Considering the characteristics of the UNWTO.Volunteers Program previously presented, the question is at what degree the goals of the program match the capacity-building determinants considered and how far it may be able, or not, to accomplish it. We will refer to the experience of Chiapas for this assessment.

The UNWTO.Volunteers program was carried out throughout eight months by trained and skilled volunteers in order to achieve a strategic tourism planning project. This was aimed at filling a knowledge gap, building on existing information and research by means of participatory methods to explore and analyse perceptions and practice of local tourism systems in the region of Chiapas in order to convert such knowledge into capacity building. This depended, in fact, on information gathered mainly from local officials, in the planning and research of secondary data previous to the fieldwork phase, and most importantly during the fieldwork from a range of local stakeholders that demonstrated to have a great base of knowledge. They were able and interested in participating in diverse in-depth interviews and discussion fora, and some of them had a very critical perspective on the local tourism system. It meant somehow to reinforce the tourism sector governance through the incentives to join different stakeholders and to trigger the discussion on their own vision of the problems and tourist potential for the region.

The collaboration among all the stakeholders was enhanced by the program which was reinforced by communication and networking, encouraging the participation of all, including the private and public sectors and civil society. Nevertheless, while all participated in the public sessions when the preliminary findings and final report were presented, it does not mean that this participative process will last over time, or that all the stakeholders will be effectively involved in the plan implementation, and that the results will be effectively communicated to all of them. For that reason, and since the fieldwork research revealed a lack of communication and networking between the diverse stakeholders, the final Plan "Chiapas 2015" suggested the creation of an institutional organism comprising stakeholders of the five municipalities in order to achieve a global strategy for the development of tourism in the whole destination. As suggested in the plan, this should integrate members of the public administration, and from the private sector and civil society of the five municipalities (UNWTO.Themis, 2009).

The program encourages the involvement of a range of local stakeholders, directly or indirectly related to the tourism development process, through individual in-depth interviews and discussion fora. Thus, the traditional local decision-makers tend at least to get more conscientious about the importance of adopting participatory methodologies to design and implement tourism strategic plans. On the other hand, one of the main goals of the programme is knowledge transfer and sharing which is likely to encourage a more active participation of the local community. As Cole (2006: 631) argues, active

participation is "frequently constrained by a community’s lack of information and knowledge". As such, the knowledge brokerage that was implicit during the fieldwork, in terms of stakeholders’ involvement, as well as with the final strategic plan based on that shared process, may contribute to enable a more active participation in the future.

The dimension of empowerment is also somehow reflected in the program as governance, knowledge and participatory approaches contributed to the enhancement of community cohesion as well as to the capacity of different stakeholders to strengthen their participation in political processes and local decision making. To increase transparency and improve governance, an enabling environment is required that ensures that citizens participate in policy making and implementation. For that reason it is crucial that the program has the full support of the local counterparts. This condition was verified in general with the five municipalities of Chiapas involved in the program.

In general, the effective results about the outcomes of this kind of interventions on the local development processes and poverty reduction through tourism are only possible in the long term, which in turn makes it difficult to judge, and assess, the impact of the program on the short term. Moreover, until now the program lacks a monitoring and evaluation follow-up plan, which although intended is not yet a reality.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Whereas there are several initiatives to combat poverty that have proven that tourism may be, for many developing countries, one of the most viable options for their economic and social development, there are still unexplored scientific arguments to support the real impacts of these programs at various levels. This research attempted to contribute to fill this gap in the scientific literature about tourism and poverty alleviation. Its essential theoretical implication was to identify the main determinants that support the wide concept of capacity building and its role in triggering poverty reduction through tourism. It has also contributed to learn more about a specific tourism program, in the context of international development cooperation, led by UNWTO. This program intends to be a global action framework to reduce poverty through tourism, with a major focus on the knowledge sharing dimension that is believed to be the driving force to reinforce the local capacity-building as it may influence the other determinants to take place. There is still however a long way to go and it will be necessary to carry out more research on a monitoring and evaluation follow-up plan. Any development effort to be effective should focus on the whole set of determinants proposed, considering the specific context of intervention.

This research also has practical implications for the planning, development and follow-up of future initiatives carried out by diverse development stakeholders. One of its direct contributions is that it provides planners and development agencies a holistic vision of the determinants that integrate the capacity building concept within the context of a tourism development system. In doing this they will get a clear sense of the determinants and their inter-relationships that need closer attention to be worked on a specific context of a development initiative. If the development programs manage to have a positive influence on all, or at least in some of the dimensions and its inter-relationships, then it is possible that capacity building becomes reinforced, which will allow local stakeholders to be the authors of, and sign-off, their own development. This in turn constitutes a crucial condition for sustainable tourism development, contributing to the foremost goal that is poverty alleviation.

The discussion conducted in this paper could be enhanced with an analysis on the role of other development agencies in tourism development, coupled by the development of monitoring and evaluation approaches, as well as the lessons learned. Analyzing the nature and influence of the determinants for tourism as a development instrument, and to establish a set of indicators to measure each of them, is an important area of research that can lead to a deeper understanding of how tourism can be a valuable development strategy towards poverty alleviation.

REFERENCES

ALSOP, R., AND HEINSOP, N. (2005), Measuring Empowerment in Practice: Structuring Analysis and Framing Indicator, WB Policy Research Working Paper No. 3510, Washington, DC, World Bank. [ Links ]

ASHLEY, C., ROE, D., AND GOODWIN, H. (2001), Pro-poor Tourism Strategies: Making Tourism Work for the Poor – A review of experience, London, Overseas Development Institute. [ Links ]

BROHMAN, J. (1996), "New directions in tourism for third world development", Annals of Tourism Research, 23 (1), 48-70. [ Links ]

CHOK, S., MACBETH, J., AND WARREN, C. (2007), "Tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation: a critical analysis of pro-poor tourism and implications for sustainability", Current Issues in Tourism, 10(2/3), 144–65. [ Links ]

COLE, S. (2006), "Information and Empowerment: The Keys to Achieving Sustainable Tourism", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(6), 629-44. [ Links ]

COOPER, C. (2006), "Knowledge Management and Tourism", Annals of Tourism Research, 33 (1), 47–64. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. (1998), Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions, London, Sage. [ Links ]

DFID (1999), Sustainable Tourism and Poverty Elimination Study, http://www.propoortourism.org.uk/dfid_report.pdf. [ Links ]

DINICA, V. (2009), "Governance for sustainable tourism: a comparison of international and Dutch visions", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (5), 583–603. [ Links ]

EADE, D. (1997), Capacity-Building: An Approach to People-Centred Development, Oxford UK and Ireland, Oxfam. [ Links ]

FRITZ, V., AND MENOCAL, A. R. (2007), "Developmental States in the New Millennium: Concepts and Challenges for a New Aid Agenda", Development Policy Review, 25 (5), 531-52. [ Links ]

GRINDLE, S. (2007), "Good Enough Governance Revisited", Development Policy Review, 25 (5), 553-74. [ Links ]

HALL, D. AND BROWN, F. (2006), Tourism and Welfare, Wallingford, CABI. [ Links ] HARRISON, D. (2008), "Pro-poor tourism: a critique", Third World Quarterly, 29 (5), 851–68. [ Links ]

LIMA, S., EUSEBIO, C. AND PARTIDARIO, M. R. (2011), "Tourism and poverty alleviation: the role of the international development assistance", in Sarmento, M., and Matias, A., (eds) Economics and Management of Tourism: Tendencies and Recent Developments, Lisbon, Universidade Lusíada Editora, Colecção Manuais. [ Links ]

NADKARNI, S. (2008), "Knowledge Creation, Retention, Exchange, Devolution, Interpretation and Treatment (K-CREDIT) as an Economic Growth Driver in Pro-Poor Tourism", Current Issues in Tourism, 11 (5), 456-72. [ Links ]

NOVELLI, M., SCHMITZ, B. AND SPENCER, T. (2006), "Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: a UK experience", Tourism Management, 27, 1141–152. [ Links ]

OCDE (2005), Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/56/41/38604403.pdf [ Links ]

PARTIDARIO, M. R., AND WILSON, L. (2010), "Institutional and Professional Capacity-Building for SEA", in Sadler, B., Aschmann, R., Dusik, J., Fischer, T., Partidário, M. R., and Verheem, R., (eds) Handbook on Strategic Environmental Assessment, London, Earthscan. [ Links ]

ROMANOW, P., AND BRUCE, D. (2006), "Communication and Capacity Building: Exploring Clues from the Literature for Rural Community Development", Journal of Rural and Community Development, 1, 131-54. [ Links ]

RUHANEN L., COOPER C., AND FAYOS-SOLÁ E. (2008), "Volunteering Tourism Knowledge: a case from the UNWTO", in Lyons, K. D., and Wearing, S., (eds) Journeys of Discovery in Volunteer Tourism, Wallingford, CABI. [ Links ]

SHARPLEY, R., AND NAIDOO, P. (2010), "Tourism and Poverty Reduction: The Case of Mauritius", Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 7 (2), 145-62. [ Links ]

SHAW, G., AND WILLIAMS, A. (2009), "Knowledge transfer and management in tourism organisations: an emerging research agenda", Tourism Management, 30, 325–35. [ Links ]

SHEATE W. R., AND PARTIDARIO M. R. (2010), "Strategic approaches and assessment techniques-Potential for knowledge brokerage towards sustainability", Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 30, 278-88. [ Links ]

SCHEYVENS, R. (2007), "Exploring the tourism-poverty nexus", Current Issues in Tourism, 10 (2/3), 231-54. [ Links ]

SCHILDER, D. (2007), "Growth versus equity: the continuum of pro-poor tourism and neoliberal governance", Current Issues in Tourism, 10 (2/3), 166-92. [ Links ]

SOFIELD, T. (2003), Empowerment for Sustainable Tourism Development, Pergamon, Oxford. [ Links ]

TOSUN, C. (2000), "Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries" Tourism Management, 21, 613-33. [ Links ]

UNDP (2000), Good Governance: a User’s Guide, http://gaportal.org/sites/default/files/undp_users_guide_online_version.pdf

UNWTO (2009), Cooperation Activities, http://ekm.unwto.org/english/activities.php. [ Links ]

UNWTO.Themis (2009), Proyecto Chiapas 2015: Plan de estrategia y Competitividad Turística para los Clusters de Tuxtla Gutiérrez, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Palenque, Comitán de Domínguez y Chiapa de Corzo, Report prepared for UNWTO.Themis, Andorra, UNWTO.Themis (unpublished). [ Links ]

WHITE, R. (2004), "Is ´Empowerment’ The Answer? Current Theory and Research on Development Communication", Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies, 66 (1), 7-24.

YIN, R. K. (2003), Case study research: Design and Methods, Third edition, Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi, SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

ZHAO, W., AND RITCHIE, J. R. B. (2007), "Tourism and poverty alleviation: an integrative research framework", Current Issues in Tourism, 10 (2), 119-43. [ Links ]

Submitted: 25.09.2011

Accepted: 28.10.2011