Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.9 no.1 Faro 2013

The influence of teenagers on a family’s vacation choices

A influência dos adolescentes no processo de compra de viagens de lazer

Maria Teresa Borges Tiago1, Flávio Gomes Borges Tiago2

Department of Business and Economics, University of the Azores, Portugal; 1mariaborges@uac.pt; 2flaviotiago@uac.pt

ABSTRACT

Family decision-making research has frequently examined the roles of adults and children on purchase decisions. Empirical results show a propensity toward a joint decision process in problem recognition and the final decision stages. This article argues that teenagers’ influence on a family’ buying decisions suffers from a certain conceptual and definitional ambiguity, and oversimplification regarding the different modes of influence. Nevertheless, there is a consensus in business and academia that kids in general have an increasing influence in the decision making process of families.

Thus, the objectives of this research are to measure teenagers’ and parents' perceptions regarding tactics used by both, especially pester power, in the context of the decision-making process for a family’s travelling choice and for breakfast cereals. The research aims to assess the differences driven by demographic characteristics.

Keywords : Teenagers, family decision-making, vacations, tourism.

RESUMO

A interação e influência das crianças e dos adultos nos processos de decisão de compra familiares têm sido alvo de inúmeros trabalhos académicos. As evidências empíricas apontam para uma decisão partilhada, quer na fase de reconhecimento do problema, quer nas últimas etapas do processo de decisão. Neste artigo a tónica é colocada na influência e nas táticas negociais empregues pelos adolescentes nesse processo familiar, que não tem sido alvo de grande atenção, apesar da reconhecida importância deste segmento, tanto pelos investigadores como pelas empresas. Assim, procura-se com este trabalho aferir as perceções e as táticas empregues pelos adolescentes e pelos seus progenitores com relação a dois tipos de produtos: viagens de lazer e cereais para pequenos-almoços. A escolha de dois tipos de produtos com tipologias e complexidade diferente permite retirar ilações quanto aos padrões empregues e à influência das caraterísticas demográficas no comportamento familiar de decisão de compra.

Palavras-chave : Processo de decisão de compra, adolescentes, viagens de lazer, turismo.

1. Introduction

In 2011, international tourism generated US$ 1.030 billion (€ 740 billion) in export earnings. UNWTO forecasts a growth in international tourist arrivals of between 3% and 4% in 2012. When looking at the different segments of tourism, one of the growing segments is the family traveler (travelers with children or grandchildren between the ages of 0-18 years). Last year, this segment represented almost 30% of U.S. adult leisure travelers.

From the very simple to the very complex, decision-making is something that consumers have to deal with several times a day in their daily lives, whether as an individual or as a family. The usual approach to family decision-making assumes that the two parents who have formed or are considering forming it, pool their incomes and maximize a neoclassical household utility function, subject to the total income constraint and the time constraints (Manser & Brown, 1980), but it also includes kids’ influence on the parents’ decision-making process.

Studies in several countries show that the social role of young people has changed over time. Young people, teenagers or even small children are better informed and richer than they have ever been, and play a critical role in the family decision-making structure. Thus, emphasis is placed on familial influences to capture contemporary family interactions in relation to purchases, communication and decision-making.

Since behavioral characteristics of youth are very different from those of adults, this demographic should be treated in a specific and appropriate manner, considering its stages of cognitive development and its consumption needs. Therefore, our aims are to contribute to the understanding of the influence tactics most used by teenagers in the purchase process, to determine the effectiveness of these tactics and the nature of influence used related to product type, and establish a relationship between the type of households and the tactics used.

This paper has five sections and is organized as follows. Section 1 contains a brief background for this research. Section 2 presents a literature review surrounding the role of young people in the family decision-making process. An evaluation framework is developed in section 3, as well as a set of hypotheses. In the last two sections we conclude our study, reiterate the major points and suggest avenues for further investigation.

2. Literature review

Many (if not most) important decisions are not made by one person acting alone, and most consumed items, such as food, are often jointly “consumed” (Davis, 1976). Therefore, families are by nature a relevant unit for studying consumer behavior. The research on family decision-making has tended to examine disparities in spousal influence; the role of the young family members was often neglected (M. Belch & Willis, 2002; Davis, 1976; Kozak, 2010; Manser & Brown, 1980; Su, Fern, & Ye, 2003).

To determine how a family makes buying decisions and how it affects the future purchasing behavior of its members, it is very helpful to understand the functions provided by the family and the roles played by its members in the decision-making process (see Figure 1).

Figure 1During the investigation of family decision processes, four stages take place. The first explores how a family decides and the roles played by the couple; the second analyses how spouses act in terms of wielding influence in spousal conflict resolution during a decision ( Corfman & Lehmann, 1987); the third emphasizes a joint decision-making process in greater detail with a focus was on how partners discuss the matter and which influence tactics are used (Kirchler, 1995); the fourth assumes the existence of new roles and patterns inside the families as well as reflecting on the almost natural click-buying decision-making of teens.

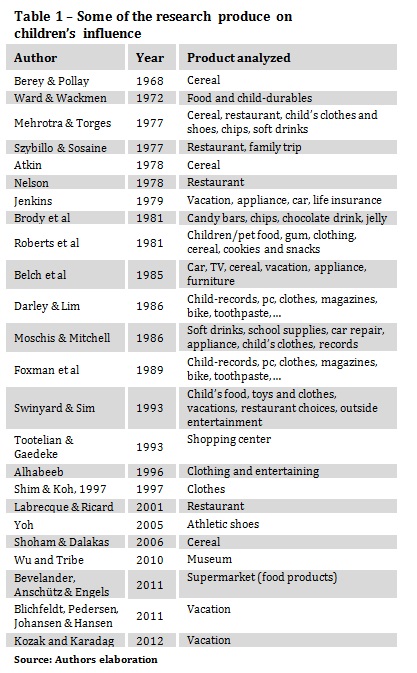

Going beyond the second phase, several studies focused on the growing influence of children in family decision-making and interviewed children as well as parents about the children’s influence (Labrecque & Ricard, 2001). Most of these were produced and published in the 1970s and 1980s (see Table 1).

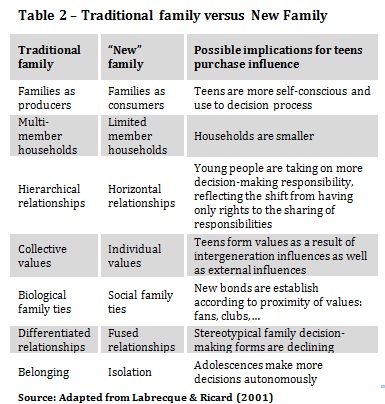

Over the last four decades, family structures all over the world have undergone profound modifications, especially in developed countries. These trends changed family characteristics and how young people were perceived by society. Some of the major social transformations present in modern societies are related to delayed marriages, older parents, postponed childbearing, single-parent families, reconstituted families and stepfamilies as well as other individual phenomena, such as the growing participation of women in the labor market (Flurry, 2007). All these transformations have significantly altered the social statuses of children and adolescents within the family, and contributed to the construction of a youthful image and demarcation of independent decision-making (see Table 2).

For a long time, young people were considered subjects with less developed psycho-cognitive processes and experiences than those of older age, and therefore scant attention was given to their opinions and expressions on any subject, even those most relevant to them. Since the 1980s, this perspective has undergone profound changes, including the increasing buying activities performed by these teens.

Studies in the United States show, through percentages and monetary values, the great importance of the youth segment for marketers. Since 1997, the influence of children on parental purchasing decisions increased by 54%; they influence 80% of household expenditures on food (Flurry, 2007). In the late 1990s, youth-focused marketing reports show that American children influenced $188 billion directly and $300 billion indirectly in parents’ purchasing behavior (Shoham & Dalakas, 2006). Similar evidence exists in other parts of the world, such as China. Chinese children (ages seven to 11) influence 68.7% of parents' regular purchases and 23.3% of a family’s durable goods purchases (J. McNeal & Yeh, 2003). Israeli children influence more than 50% of family purchase decisions (Shoham & Dalakas, 2006).

Regarding influence, we consider the process that occurs when an individual acts in such a way to intentionally change the behavior of another individual (Cartwright & Roth, 1957). In this sense, children and teenagers become responsible for selling many products through their influence on the purchasing decisions of parents.

Back in 1977, Ward et al. split the family influence on children’s consumption behavior into family’s behavior variables and family’s patterns variables. These effects combined have a direct influence on the development of general cognitive abilities of young children and an indirect influence on the development of children’s consumer skills.

Children tend to act as major decision makers at purchase time. They not only decide to acquire products directly related to them but also other products that will be consumed by the family. Thus, the youth market has increasingly attracted the attention of firms that find in this niche a new window of opportunity.

McNeal (1992) presented three divisions of the children’s market: (1) the primary market where youth are treated as end users; (2) influence market where kids are considered as direct and indirect influences on parents’ decisions; and (3) future market where youth are consider as a potential future purchase decision-makers.

The influence of young people in the family decision-making process has been widely studied, yet only a few works have been produced regarding the specific role of teenagers (M. Belch & Willis, 2002; M. A. Belch, Krentler, & Willis-Flurry, 2005; Foxman, Tansuhaj, & Ekstrom, 1989; Hunter-Jones, 2004; Mittal & Royne, 2010; K. Palan & R. Wilkes, 1997; Shoham & Dalakas, 2006).

Understanding the factors affecting the influence of the adolescent in family purchase decisions is a challenge, since this segment has gained much more power over the last two decades. In different studies, several variables are presented and their use varies from author to author. However, the most common are: the importance of the product or service and its use by adolescents, the stages of the buying decision, the influence strategies used and demographic variables relating to adolescents and parents.

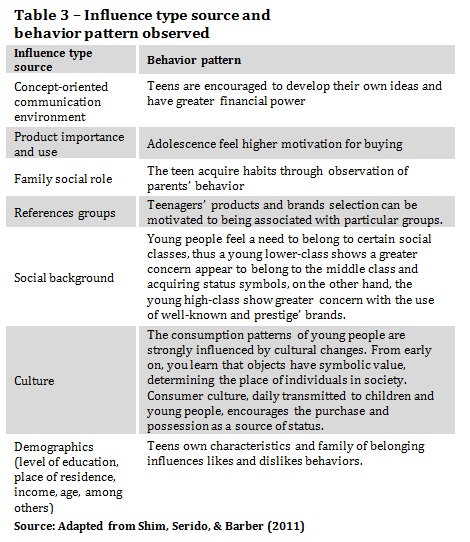

As noted by Isler, Popper, and Ward (1979) small children have huge purchasing power, even though they don’t spend their own money and just ask for products. On other hand, adolescents tend to be more avid consumers since they are at the initial stage of using their own money—in some cases with credit cards — and also have additional influence on family buying patterns. As surveys show, teenagers tend to be sophisticated consumers and use a variety of influence strategies on their parents (Shim, Serido, & Barber, 2011). Palan and Wilkes (1997) provided a categorization of influence strategies used by adolescents to influence the outcome of the family decision-making process. These persuading techniques vary according to the purchase decision stage — problem recognition, information search choice and decision-making. And they tend to determine the behavior patterns observed across decision stages, as found by most of the research. Nevertheless, the use of the different techniques is not done in a separate mode, reflecting other sources of influence, as presented below (see Table 3).

According to McNeal and Yeh (2003), the categories in which young people have a great influence on families’ buying decisions can be divided into three major areas:

a) Items for themselves. This area includes snacks, clothing and electronics.

b) Items for home. Young people also influence their parents regarding objects and furniture for the house.

c) Items for family members outside the home. These items include holidays, cars and restaurants.

In order to gain a full understanding of the parent-adolescent purchase relationship, this work closely examines the key construct of pester power, counting the teen’s influence on family consumption.

According to Ghani & Zain (2004), there is now a unique market position of young consumers and their spending power and influence, which has resulted in increasingly large budgets. This has led to several opposing viewpoints. On one side, authors focus on the highly influential marketing process used to sell products to teens, also known as pester power. Most of these works attempted to understand the impact of advertising on teens’ purchasing behavior and influence, assuming that adolescents are highly persuaded by media ads and have conditional/emotional behaviors subsequent to exposure. However, Nash (2009) pointed out that the use of the pester power definition can sound pejorative to the industry practitioners, since it emphasized the use of promotional strategies aimed at young people, encouraging unwanted purchase requests to the family.

Empirical studies have acknowledged that adolescents use a number of different influence attempts, including, but not limited to, asking, pleading, bargaining, persisting, using force, telling, being demonstrative, sugar-coating, threatening, and using pity (Atkin, 1978; Isler et al., 1987; McNeal, 1992; Williams and Burns, 2000).

As Al-Zu'bi et al. (2008) noted, parents tend to have few educational goals in their minds regarding their consumer role, and therefore young people tend to use pester power to obtain the product or service they want. In their work, Proctor and Richards (2000) claimed that research concerning pester power must be established using more precise descriptions of what occurs in parent-teen purchase relationships beyond the initial requests and pleading forms. This is the path that will be followed in the next sections.

Evaluation Framework and Hypotheses

One of the potential global segments is the dot.com generation, which grew up technologically knowledgeable, socially active and with a high influence on household decision-making.

In accordance with Piaget’s theory, Roedder (1999) suggested that young people are able to: (i) make or influence consumer decisions in a more adaptive manner as compared to their younger counterparts; (ii) adopt a more strategic posture regarding consumption; cast a wider net in the information search stage; and (iii) have more sophisticated and rational strategies regarding requests and pleading to suit the situation or answer the objections of parents.

As showed in the abovementioned literature review, family power dynamics tend to change through the years. Children and adolescents in particular have gain power in the last two decades. Often a family travel group consists of the nuclear family; therefore analyzing the family dynamic is crucial to understand the choices made in vacation planning and decision-making (Blichfeldt, Pedersen, Johansen, & Hansen, 2011; Dunne, 1999;Thornton Gareth & Williams, 1997 ). There are two central questions that arise when studying this subject: 1) Do families allow adolescents to have power and control over their spending regarding leisure travel? 2) Do they use the same approaches in order to influence family purchase decisions in the case of vacations or daily life products?

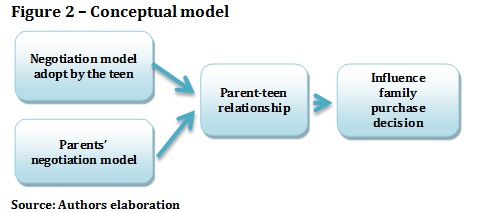

In order to fully answer these questions, a framework was developed. The goal is to update previous findings with respect to adolescent influence on family purchase decisions, particularly major purchase decisions for products and services used by the entire family (Beatty & Talpade, 1994; Foxman, et al., 1989) and compare those to the decisions regarding family vacations. For this purpose, the following model was adopted (Figure 2).

It is acknowledged that the family’ decision-making process relies on the parent-teen relationship, which encompasses many facets including social, consumption and behavioral aspects.

One basic characteristic considered in buying behavior is gender and the inequality between males and females. As noted by Flurry (2007), research over time indicated that female children were more influential than were male children across all stages of the decision-making process. These assessments found an exception in Chinese culture, as found by Pervan and Lee (1998). Considering the family changes occurring over the past two decades, such as postponed childbearing, single parent households and fused relationships, it is suggested that the moderating effect of gender may no longer be in effect. Therefore, hypothesis one is designed to test the proposition that no differences derived from children’s gender can be found in their purchase influence:

H1. No difference in purchase decision influence will be found between male and female teenagers.

Looking at traditional models of vacation decision-making (e.g. Mansfeld, 1994; Um & Crompton, 1990), we find that the starting point of the vacation decision-making process is considered to be the making of the generic decision whether to go or not to go on vacation. Usually this type of decision is tightly connected to the parents’ cultural background and to their social status. Research on the effects of family socio-economic status on young people’ influence has been mixed; most of the research measured household income and parents' education levels (Shoham and Dalakas, 2006). For that reason, the second hypothesis developed here is concerned with parents’ background impact on their negation model, as well as the teen negation approach when deciding to go or not to go on vacation.

H2: Young people whose parents have attained higher educational levels will have more influence on purchase decisions than will young people whose parents have attained lower educational levels.

Palan and Wilkes (1997) examined persuading techniques used by teenagers within a family consumption context. These authors found a relationship between influence tactics and parental response strategies. Past researchers have acknowledged that young people use a number of different influence attempts, such as asking, pleading, bargaining, persisting, using force, telling, being demonstrative, sugar-coating, threatening, and using pity (Isler, et al., 1979; J. U. McNeal, 1992; Williams & Burns, 2000). McNeal and Yeh (2003) suggested that these young people’s tactics vary in accordance with the typology of product and moment/nature of consumption. The work of Shoham & Dalakas (2006) produced some interesting findings, e.g. that influence tactics are used differentially with varying effectiveness, but are product-invariant for the most part. Furthermore, Bevelander et al. (2011) found that young people spent their money readily on food and snacks; in this domain, they tend to adopt rational strategies of requests and pleading. These authors found that this behavior tends to decline over time, as clothing and entertainment products become more important at older ages and more sophisticated negotiation techniques start to be employed. Considering this, the influence of teenagers on vacation travel choices should vary as well as their influence tactics (Blichfeldt, et al., 2011). The results should also be quite different when comparing adolescent influence regarding daily family product consumption or the choice of family vacations. With this in mind, the third and fourth hypotheses are:

H3: Teenagers use different influence tactics with varying effectiveness.

H4: Teenagers use different influence tactics when negotiating a convenience product (breakfast cereals) or a tourism product.

Almost 40 years ago, Davis (1976, p. 241) stated that “ the number of products that an individual always buys for individual consumption must certainly represent a very small proportion of consumer expenditure ”, leaving a considerable part of purchasing decisions to a complex family dynamic model. Unveiling the influence of young people on this model is the aim of this work. Thus the different tactics of persuasion are analyzed, considering a daily-basis product (breakfast cereals) and a more complex product (family vacation destination).

Methodology

Beyond the borders of the U.S. and Asian countries, little or no empirical studies have been done regarding young people’s consumer behavior. As such, the present work focuses on Portuguese adolescent habits regarding tourism products.

Group interviews and face-to-face self-administered questionnaires, including drop-off and pick-up, were respectively employed to solicit responses from adolescents and their parents.

The group interviews were conducted during regular classroom hours with cooperation by the schools’ administrations. Data were collected in urban and middle-class preferential schools.

In this study, the questionnaire contained a similar structure to the one used by Shoham and Dalakas (2006). Therefore, the questionnaire included questions on adolescents’ influence tactics regarding two products – breakfast cereals and traveling products. Parental yielding was also assessed in this survey.

Results

A convenience sample (n= 119) of youth ranging from 10 to 12 (34,5 percent), from 13 to 15 (30,3 percent) and from 16 to 18 (35,3 percent) was chosen from four schools in coordination with the schools’ administration boards. Slightly more than half of the respondents (55,5 percent) were girls and the remaining (44,5 percent) boys.

Parents’ education levels ranged from primary, elementary school and secondary school (55,5 percent), to diploma (26,9 percent) and bachelor and higher education (17,6 percent). There are two additional remarks that need to be made: (i) average monthly household income was slightly higher than the national average, and that can reflect the selection of schools; (ii) the youth inquiries are in the context of planning one trip/year. Since the sample was collected in an island context, it stands to reason that for holidays, typical families try to go somewhere different.

The results achieved regarding tactics’ frequency of use and effectiveness in the family decision process is presented in Table 4.

The patterns of most tactical choices are remarkably similar between the two different products of breakfast cereal and family trips. However, the second most-used tactic is begging and whining and the third choice is negation with logical arguments. In the case of the cereals, these tactics were adopted and deemed effective in a similar order. However, begging and whining proved to be an ineffective tactic for a teenager when trying to influence the family vacation decision process (46.3% of use against 10.9% of effectiveness). Social influence from their peers is also a non-effective tactic (21.9% of use against 14.2% of effectiveness).

Thus, it appears that the influence tactics and parental acquiescence do not form a continuum for both types of products, as found in previous studies. There is a clearly ordered pattern of usage and effectiveness of tactics in the case of the breakfast cereals. However, a different pattern was found for travelling choices.

Looking at the tactics adopted by three main subsets of the sample (10 to 12; 13 to 15; 16 to 18 years old) regarding tourism products, it is clear that the younger children tend to use more emotional-based strategies, such as begging, whining and persistence. The subset of 16 to 18 years old shows a higher use and influence of social references, revealing the relevance of their peers. This segment and the 13- to 15-year-old segment also disclosed that they tend to use guilt as strategic option.

We used general linear modeling to answer the remaining research questions. The evidence found in the literature led us to establish a priori four sets of interrelated dependent variables that derive from two suppositions: (i) the adoption of any influence tactic reduces the likelihood to adopt another tactic; and (ii) when a parent tends to succumb to one tactic, the likelihood he/she will also yield to another is reduced. In our research, 32 influence tactics and yielding were considered as dependent variables; adolescent’s gender and age, parent’s education level, and family income were the independent variables used.

The analysis yielded 128 analysis of variance (ANOVA) models. Of these, eleven were significant at p < 0,05 and another six at p <0,10. The Eta 2 for the 17 models varied between 2,6% percent and 9 percent. The results suggested that adolescents’ gender had little importance in explaining the frequency of use of the tactics by adolescents. However, adolescents’ gender was found to be significant in the choice of the tactics used to influence family vacation decisions: deals (sig=0,079; Eta2= 0,026) and screaming, shouting, anger, and getting mad (sig=0,036; Eta 2= 0,037). Furthermore, gender was found to affect the likelihood of parents yielding to adolescents’ requests.

To assess the possible impact of parental education level on young adults’ influence tactics and on yielding to these tactics, an analysis of variance was performed (6 of 32 the ANOVA models were significant). The results found that parents’ educational levels affect the choice and yielding, especially regarding breakfast cereals. The Eta2 suggested a higher level of pester power (0,062) when teens use the tactic of begging and whining in the choice of vacation destinations, especially for those parents with lower educational levels.

Our findings support the conceptual framework regarding hypotheses three and four, since there is a clearly ordered pattern of usage and effectiveness of tactics in the case of the breakfast cereals. However, a different pattern was found when analyzing the tourism product choices. Our results did not support the first two hypotheses. First, evidence showed that adolescent gender has significant impact on the choice of the tactics used to influence family vacation decisions. Secondly, the results indicated that youth whose parents have attained lower educational levels have more influence on purchase decisions than will youth whose parents have attained higher educational levels.

Conclusions and suggestions for further investigation

The influence of youth on family decision-making occurs when they act to modify the purchasing behavior of their parents or guardians. The information that teens transmit is selected according to their needs and wants, and they act in such a way to change and influence the purchase procedure with the aim of acquiring a product that pleases them. In this way, the intensity of influence used by young people tends to depend on two factors: their assertiveness and the tendency of parents to be acquiescent to their requests.

Upon examination and reflection of the literature, it became apparent that the adolescent influence on the family purchase decision process has not been adequately documented, especially regarding more complex products such as family vacations. Therefore, the aim of this work is to contribute to a deeper understanding of youthful consumer behavior regarding tourism products, to uncover new meanings associated with this phenomenon and to compare it to a convenience product decision-making process.

The results generated some interesting findings. First, it was shown that the tactics adopt by young people to influence family consumption patterns vary when considering a convenience product or a more complex product, such as tourism products. The results also show that in the case of cereals, teens tend to use the tactics that present a higher level of effectiveness. Our results also confirm that teenagers’ influence on vacation travel choice varies as well as the influence tactics they adopted (Blichfeldt, et al., 2011). The difference obtained regarding these two products are in accordance with the study by McNeal and Yeh (2003). One of the findings is that parents tend to acquiesce more to appeals made by younger children.

The work of Shoham & Dalakas (2006) did not find differences between gender regarding tactics adoption and pester power. However, our results show that in terms of tourism products, there are significant differences between girls and boys regarding tactics adopted and their effectiveness. Girls tend to influence parents more regarding tourism products.

Aside from this, the analysis reveals another different result from the work by Shoham & Dalakas (2006). These authors found evidence of higher pester power in parents with higher educational levels. But in our case, the results found that young people whose parents have attained lower educational levels will have more influence in purchase decisions than will young people whose parents have attained higher educational levels. This leads us to conclude that teenagers in highly educated households have less pester power, and therefore their influence on family tourism product decisions is lower.

The results allow us to make three major conclusions regarding adolescent influence on family tourism product choices: (i) there are three distinctive groups of teens that adopt different tactics, which correspond to a gradient from emotional to rational during their growing process and have distinctive outcomes for family decision processes; (ii) girls are more effective in influencing family decisions regarding travelling and vacation choices; and (iii) family educational background, usually tightly connected to income and past tourism experiences, influence parents’ acquiescence to youth tactics.

This information gathered here is beneficial to tourism marketing managers, who can use it to redirect their marketing strategies and target more youth segments. Since three distinctive segments were found, marketers can promote different strategies for each of these segments. To the youngest segment, marketing can emphasize the emotional dimension usually used by those children. The oldest segment can be target with more rational and elaborate messages, since it has been found that these teenagers process highly rational messages and use this same approach with parents. They also can use this knowledge to reach parents directly or indirectly through their teenagers, especially girls, since girls show a higher influence on the family decision process.

However, these findings should be viewed in light of some limitations. Further work is clearly needed to examine the inclusion of other variables, such as cultural dimensions and/or family background regarding tourism product consumption, such as past tourism experiences. Moreover, it would be interesting to enlarge this convenience sample and collect data in different countries. Certainly, there is ample scope for further research in this area.

Acknowledgement : Funding for this work is granted by FCT – CEEAplA, Research Center for Applied Economics and data gathered by Carmen Queirós.

References

Al-Zu'bi, A., Crowther, G., & Worsdale, G. (2008). Jordanian children's perception of fathers' communication structures and patterns: scales revision and validation. Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 9(4), 265-281. [ Links ]

Beatty, S., & Talpade, S. (1994). Adolescent influence in family decision making: a replication with extension. Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (2), 332-341. [ Links ]

Belch, M., & Willis, L. (2002). Family decision at the turn of the century: has the changing structure of households impacted the family decision making process? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 2(2), 111-124. [ Links ]

Belch, M. A., Krentler, K. A., & Willis-Flurry, L. A. (2005). Teen internet mavens: influence in family decision making. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 569-575. [ Links ]

Bevelander, K. E., Anschütz, D. J., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2011). Social modeling of food purchases at supermarkets in teenage girls. Appetite, 57, 99-104. [ Links ]

Blichfeldt, B. S., Pedersen, B. M., Johansen, A., & Hansen, L. (2011). Tweens on Holidays. In-Situ Decision-making from Children's Perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(2), 135-149. [ Links ]

Cartwright, D. S., & Roth, I. (1957). Success and satisfaction in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 13, 20-26. [ Links ]

Corfman, K., & Lehmann, D. (1987). Models of cooperative group decision-making and relative influence: An experimental investigation of family purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(1), 1-13. [ Links ]

Davis, H. L. (1976). Decision Making within the Household. The Journal of Consumer Research, 2(4), 241-260. [ Links ]

Dunne, M. (1999). The role and influence of children in family holiday decision making. International Journal of Advertising and Marketing to Children, 1(3), 181-191. [ Links ]

Flurry, L. A. (2007). Children's influence in family decision-making: Examining the impact of the changing American family. Journal of Business Research, 60(4), 322-330. [ Links ]

Foxman, E., Tansuhaj, P., & Ekstrom, K. (1989). Family members' perceptions of adolescents' influence in family decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 482-491. [ Links ]

Ghani, N. H. A., & Zain, O. M. (2004). Malaysian children’s attitudes towards television advertising. Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 5(3), 41-51. [ Links ]

Hunter-Jones, P. (2004). Young people, holiday-taking and cancer: an exploratory analysis. Tourism Management, 25(2), 249-258. [ Links ]

Isler, L., Popper, E., & Wart, S. (1979). Children's Purchase Requests and Parental Responses: Results from a Diary Study. Cambridge, Mass: Marketing Science Institute. [ Links ]

Kirchler, E. (1995). Studying economic decisions within private households: A critical review and design for a “couple experiences diary”. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(3), 393-419. [ Links ]

Kozak, M. (2010). Holiday taking decisions-The role of spouses. Tourism Management, 31(4), 489-494. [ Links ]

Labrecque, J., & Ricard, L. (2001). Children's influence on family decision-making: a restaurant study. Journal of Business Research, 54(2), 173-176. [ Links ]

Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and household decision-making: A bargaining analysis. International Economic Review, 21(1), 31-44. [ Links ]

Mcneal, J., & Yeh, C. (2003). Consumer behavior of Chinese children: 1995-2002. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(6), 542-554. [ Links ]

Mcneal, J. U. (1992). Kids as Customers: A Handbook of Marketing to Children. New York: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Mittal, B., & Royne, M. (2010). Consuming as a family: Modes of intergenerational influence on young adults. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9 (4), 239-257. [ Links ]

Nash, C. (2009). The parent child purchase relationship. (Masters thesis, Dublin Institute of Technology, 2009). Retrieved from http://arrow.dit.ie/busmas/24/. [ Links ]

Palan, K., & Wilkes, R. (1997). Adolescent-parent interaction in family decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(2), 159-169. [ Links ]

Pervan, S., & Lee, C. C. K. (1998). An observational study of the family decision making process of Chinese immigrant families. Asian-Pacific Advances in Consumer Research, 3, 20-25. [ Links ]

Shim, S., & Koh, A. (1997). Profiling adolescent consumer decision-making styles: Effects of socialization agents and social-structural variables. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 15(1), 50-59. [ Links ]

Shim, S., Serido, J., & Barber, B. L. (2011). A consumer way of thinking: linking consumer socialization and consumption motivation perspectives to adolescent development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 290-299. [ Links ]

Shoham, A., & Dalakas, V. (2006). How our adolescent children influence us as parents to yield to their purchase requests. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(6), 344-350. [ Links ]

Su, C., Fern, E., & Ye, K. (2003). A temporal dynamic model of spousal family purchase-decision behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 268-281. [ Links ]

Thornton Gareth, P. R., & Williams, A. M. (1997). Tourist group holiday decision-making and behaviour: the influence of children. Tourism Management, 18(5), 287-297. [ Links ]

Tootelian, D. H., & Gaedeke, R. M. (1993). The Team Market: An Exploratory Analysis of Income, Spending and Shopping Patterns. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 9(4), 35-44. [ Links ]

Ward, D., Wackman, B., & Wartella, E. (1977). How Children Learn to Buy: The Development of Consumer Information Processing Skills. Beverly Hills: SAGE. [ Links ]

Williams, L. A., & Burns, A. C. (2000). Exploring the dimensionality of children's direct influence attempts. Advances in consumer research, 27, 64-71. [ Links ]

Article history

Received: 30 June 2012

Accepted: 04 September 2012