Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Tourism & Management Studies

versão impressa ISSN 2182-8458

TMStudies vol.9 no.1 Faro 2013

The relationship between organizational culture and the transfer of management, functions and roles in the SMES succession: A case study between Hungary and North of Portugal

A relação entre cultura organizacional e transferência de gestão, funções e papéis na sucessão nas PME: um estudo de caso entre a Hungria e o Norte de Portugal

José Paulo Machado da Costa1, Eszter Bogdány2

1 Escola Superior de Tecnologias de Fafe – Portugal, paulocosta@e-prof.org

2 University of Pannonia – Hungary, bogdany.eszter@gtk.uni-pannon.hu

ABSTRACT

This article presents the results of a study about the analysis of the relationship between organizational culture and the transfer of management, functions and roles in the succession of SME's. The study is based on a questionnaire directed to the entrepreneurs and managers of SME's. The purpose of this article is to present the results of the last edition of the questionnaire and a comparison between companies in Hungary and in the north of Portugal.

The research focuses on the mapping of the state of succession (measured by the distribution of the transferred managerial functions/roles), and examine the influence of the organizational culture. What kind of culture? what kind of role will be passed? About the organizational culture: The empirical development of the Competing Values Framework was completed by Quinn & Rohrbaugh (1981) who simply wanted to find the most important criteria and factors of effective organizational operation. As a starting point, Campbell's list of 39 effectiveness indicators was used. It allowed the comprehensive description of organizational effectiveness. Some of the 39 indicators corresponded; as a result clusters could be created.

In the article we conclude with the characterization of the relations between four dimensions of organizational culture: the hierarchy form, the Market type, the clan form of organization and the adhocracy, were defined along two axis (internal/external focus versus stability/flexibility). About the managerial roles, we focus on three management roles that can be find in the literature: the governor, the leader and the manager.

Keywords: small and medium-sized enterprises (SMES), knowledge (k), knowledge management (km), succession.

RESUMO

Este artigo apresenta os resultados de um estudo sobre a análise da relação entre cultura organizacional e transferência de gestão, funções e papéis na sucessão das PME. O estudo é baseado num questionário dirigido a empresários e gestores de PME. O objetivo deste artigo é apresentar os resultados da última edição do questionário e uma comparação entre as empresas na Hungria e no norte de Portugal.

A investigação centra-se no mapeamento do estado da sucessão (medido pela distribuição das funções de gestão transferidas) e examina a influência da cultura organizacional. Que tipo de cultura? Que tipo de papel será passado? Sobre a cultura organizacional: O desenvolvimento empírico do Competing Values Framework foi completado por Quinn & Rohrbaugh (1981), que simplesmente queriam saber quais os mais importantes critérios e fatores de funcionamento organizacional. Como ponto de partida, foi utilizada a lista de 39 indicadores de eficácia de Campbell. Isso permitiu a descrição completa da eficácia organizacional. Alguns dos 39 indicadores corresponderam; consequentemente puderam ser criados clusters.

O artigo conclui com a caracterização das relações entre quatro dimensões da cultura organizacional: a forma de hierarquia, o tipo de mercado, a forma de organização do clã e adhocracia foram definidos ao longo de dois eixos (foco interno / externo versus estabilidade / flexibilidade). Sobre as funções de gestão, o artigo centra-se nas três funções de gestão que podem ser encontradas na literatura: o governador, o líder e o gestor.

Palavras-Chave: Pequenas e médias empresas (PME), conhecimento, gestão do conhecimento, sucessão.

1. Introduction

SMEs are in an increasingly difficult situation in the current economic downturn. Continuous changes have strong impact on their operations. To meet the challenges, a spirited leader is essential. Small enterprises are not just scaled-down versions of large companies, but their operations are based on entirely different principles (Storey, 1994, p. 74).

In the end of the 20th century the literature concerned more and more with micro-, small- and medium sized enterprises (SME).

2. Literature review

Succession in small- and medium sized enterprises is a major research topic in recent years especially those are in focus where leading is in the hand of the owner. According to the European Commission in the next 10 years around 6 million SME owners will retire (EKB, 2008).

This fact indicates that SMEs will need new leaders who can keep the organization alive and even through their professionalism they can make the organization grow.

SMEs have great opportunities to support and increase competitiveness and also the increasing of employment in general. There is an indispensable question: how can the organization operate after the owner passes the baton?

The research stream for succession goes back to the 1960s. More and more researchers were interested in the research of transfer of leadership and in the influential effect of that transmission. According to Brady & Helmich (1984) there is a significant effect of the succession on the organization. Despite that, only a few researchers concentrated on this research area. Nevertheless they stated that the succession is a traumatic event, a critical change process for all organizations.

Friedman & Singh (1989) approached the impact of succession to the performance in 3 perspectives:

1. succession as an inconsequential event,

2. succession as a disruptive event, and

3. succession as a rational organizational adaptation.

These three perspectives form the foundation of the basic succession theory models. It has taken several years to prove and clarify the models themselves. The basic models, the numerous and conflicted results in connection with the succession called the attention to the integration of the results.

Kesner & Sebora (1994) created an integrative model in order to call the attention of the researchers to the need of the integration. They distinguished 4 components of the succession: the antecedents, the event, the consequences, and the contingencies (Kesner & Sebora, 1994). After the integration, the results were summarized by Giambatista (2005) who examined the research results from 1994 to 2005. He examined 3 components of the research stream: the antecedents, the event, and researches which examined the antecedents and also the consequences. He highlighted the main deficiencies of the succession models. According to Giambatista (2005), the researchers did not use detailed and profound theoretical models in relation to the research of succession. He mentioned such theoretical models as the organizational learning and adaptation (Rowe, Cannella, Rankin & Gorman, 2005), change theory and inertia (Haveman, 1993; White, Smith & Barnet, 1997) or institutionalism. Nevertheless he pointed out that the research is outstanding in relation of the succession in SMEs (Giambatista, 2005).

The present succession research stream can be divided into two parts: on the one hand the effect of the leadership or the ownership transfer on the organizational performance, on the other hand the succession planning, or the succession as organizational function.

Several deficiencies could be noticed after reviewing the literature. But it does not help to create an integrative image in relation to succession because most researches focus on the examination of basic models (Fizel & D’Itri, 1997), and do not apply other models which could help integrating the results. According to Giambatista (2005) the questions of basic models are answered, it is time to overstep the examination of the contingencies. Most researches deal with the effect of the succession to the organizational performance, nevertheless the examination of the influential indicators of the succession is neglected. From a practical viewpoint the theoretically well founded researches, and the most involved actors (SMEs) of the succession are least emphasized. It would be important to find out more about the small organizations also because “succession is recognized as ubiquitous and important for organizational performance. This is especially true for smaller organizations that are in the process of moving from founder to professional management” (Kesner & Sebora 1994, p. 363). There is a need to a comprehensive viewpoint in order to understand the complex and paradox process of the succession (Berg & Smith, 1990). It is time for the researchers to understand that the transfer of leadership and management is too complex and as a result they cannot be examined solely with logical models. Most researches are based on the experiences of those researchers who were part of a succession process (Haddadj, 2006).

Resulting from the above it will be indispensable to examine the framework of the succession in order to identify indicators which not only affect the outcome of the succession but also influence the process.

There are a few researchers who examine the roles of the successor and the incumbent in the process of the succession (Wheeler, 2008; Cannella & Shen, 2001). In the process of the identification of the successor and the incumbent roles it is important to distinguish the features of the roles of leader and manager (Bass & Stogdill, 1990; Kreitner & Kinicki, 2004).

2.1. Identification the tasks of the governor, leader, manager

In order to identify the appropriate tasks in relation with the roles of the leader and manager we reviewed the most important literature. Nevertheless, for identification purposes we also made interviews with competent researchers, experts and organizational managers. It is important to note that the present literature review does not cover all leadership and management research results, our review represents only the most significant features. The aim of the review is to demonstrate such parameters which clearly define the leaders’ and managers’ tasks.

The longish research stream represents well the main differences between the managers and leaders. Table 1 exhibits the main differences:

Table 1

The role of manager is characterized by the rules, consistency, predictability and order. The main task of the manager is the efficient and effective implementation of the organizational goals by the planning, organizing, managing and controlling of the organizational resources. They believe in the rules, accept the presents’ losses with such expectation that they will win next time. The leader communicates indirectly, through messages and signals. The managers’ goal is to be what the company expects from him/her – they accept the status quo. The manager uses traditional techniques to reach the predetermined goals. They are too busy to handle difficult or impossible problems. They accept reality, focus on the systems, structures and lean on controlling. They follow a short-run viewpoint, and concentrate on the “How? and When?” questions.

The leaders’ tasks could also be itemized similar to the managers’ tasks. The equivalent of planning is the representation of attractive vision for people and marking out the way what people need to follow. The equivalent of organizing is lining up people in order to achieve the vision. The equivalent of leading is the motivation and inspiration of the people in order to stay in the right path. The leaders’ goal is working, and in order to reach goals, high and outstanding performance is expected. The roles of the leader are like a capability that allows them to influence, motivate and empower people to contribute to the organizational performance and efficiency. The leader rebels against rules, creates new approaches to the long-standing problems and give open questions to the new opportunities. The leader works in a high risk position and is ready to explore the risk and danger. The leaders’ goal is to execute the talents, motivate, coach and build trust. They are looking at the future in order to define tasks which help reach the organizational goals. The leaders’ goal is to be what you are.

The literature shows clearly what managers and leaders really do. Based on this and also based on the interviews we determined the main tasks of the leaders and managers.

Table 2 shows the main differences in the relation of the tasks:

Table 2

Beside these two roles, we also consider important that not just they could appear in the successor and the incumbent roles. We also examined the third role, the governors’ role. The governor directing the power structures is the appropriate role for owners who would like to participate in the direction of the organization but they do not want to take part in the daily operation.

The governor who dominates the decision-making channels, influences, handles the formal and informal power structures, balances between boards or bodies, lobbies, forms coalitions, maneuvers between influential bodies (Angyal, 1999). In short the governor satisfies stakeholders. The governor ensures that the organization has a clear mission; gives directions in order for the organization to have“ ou „so the organization can have a clear strategy. He or she also provides wisdom, insight and good judgment. The governor maneuvers with differing, competing, or colliding priorities, interests, values, and perspectives. “They must serve as mediator, translator, negotiator, and facilitator… To characterize these ideas succinctly: leadership answers the question “what,” management answers the question “how,” and governance answers the question “who.” Or, to put it more playfully, leadership is inspiration, management is perspiration, and governance is incorporation“ (Mclaughlin, 2004, p. 6).

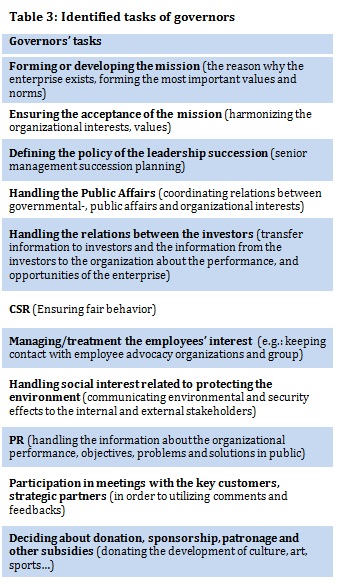

Table 3. shows the main tasks of governors:

2.2. Organizational culture

The theoretical background of our research is based on the Competing Values Framework (CVF). The CVF was completed by Quinn & Rohrbaugh (1981). They simply wanted to find the most important criteria of effective organizational operation. They created 39 effectiveness factors which resulted in 4 clusters. These 4 clusters indicated the 4 types of culture: the clan, the adhocracy, the market and the hierarchy. The Hierarchy form of organization can be characterized as a formalized and structured workplace. As a result, it is considered predictable and secure. This type of culture is held together by rules and formal regulations. The Market type of organization places a major focus on efficiency. Generally employees are competitive, leaders are authoritative, result-oriented, have high expectations and urge competition. The organization is held together by the shared values such as reaching common goals. The Clan form of organization is an accommodating workplace where people share a lot. It is like a big family. Leaders act as mentors who often step into the role of a caring parent. Team work and loyalty are principal values. Adhocracy puts an emphasis on dynamism, being adventurous, and creativity. People stick their necks out and take risks. Leaders are innovative and risk-oriented. The glue that holds the organization together is commitment to experimentation and innovation (Cameron & Quinn, 2006).

3. Methodology

The Competing Values framework was the base for a questionnaire known as the OCAI - Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument. It includes six statements that apply to the four culture dimensions.

The six groups of questions are the following:

1. dominant characteristics of the organization

2. organizational leadership style

3. management of employees

4. organizational glue

5. strategic emphases and

6. the criteria of success.

To characterize the individual dimensions, four statements were created for each of them. Respondents are asked to divide 100 points over four alternatives that correspond to the four culture types. This method measures the extent to which one of the four culture types dominates the present organizational culture. The higher the score, the more dominant a certain culture type (Cameron & Quinn, 2006). In this model, time is a crucial factor, because organizations in the early life-cycle stages mostly have an adhocracy culture. After that, this type of culture complements with the clan type, and the by the end of the process, it is completed by the elements of the market, and hierarchy. In our questionnaire it was important to examine also the desired organizational culture, which is how the leaders or the owners would see the enterprise in 5 years’ time.

In order to measure the leadership roles we created a questionnaire which includes 37 statements related to the previously revealed governor-leader-manager tasks. We asked the leaders or the owners to divide the leadership task (by using 100-point system) according to how the tasks are distributed between owner(s) and leader(s) and how this distribution would be desirable in 5 years’ time. The questionnaire was previously tested and validated by leaders and also experts in several rounds.

4. Results

The questionnaire was sent to companies in Hungary and in Portugal. The 87.5 % of the respondent Hungarian companies are family owned and the majority of the ownership is mainly Hungarian. 75% of the Hungarian companies operate in the processing industry, and 88% of the companies are small and medium size.

89 % of the Portuguese companies are family owned, and for except one respondent, the companies are fully Portuguese owned. 83 % of the respondent Portuguese companies operate in the processing industry, and 78 % of the respondents are small size companies.

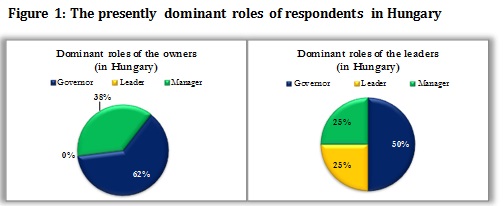

Figure 1 shows that 62% of the Hungarian owners and 50 % of the leaders deal with governors’ tasks, and all of the Hungarian company owners did not deal with the leaders’ tasks. 40% of the respondents in Hungary are owners and also leaders in the company, so most of the respondent companies’ ownership is dual. There is an interesting fact that most of the company owners did not pay attention to the leaders’ tasks, what is mostly the strategic, and vision related tasks. And also, if we examine the distribution of the dominant roles of the leaders, we can see that these leaders are competent mostly in the governors’ tasks, and 25-25 % of the respondent companies’ leaders deal with the tasks of the leader, and manager.

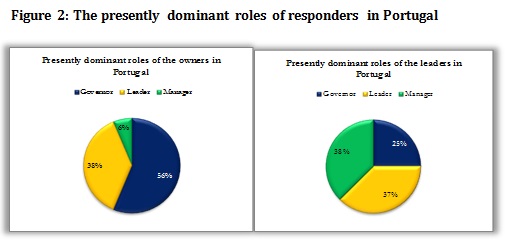

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the dominant roles in the respondent Portuguese companies. Similar to the Hungarian results the dominant roles of the owners are mostly (56%) governor, but contrary to the Hungarian results, 35% of the owners deal with the leaders’ task, and only 6% of the respondent companies’ owners handle managerial tasks. There is a harmony between the distributions of the dominant roles of the Portuguese leaders. Most of the leaders (37%and 38%) deal with both the leaders’ and the managerial tasks.

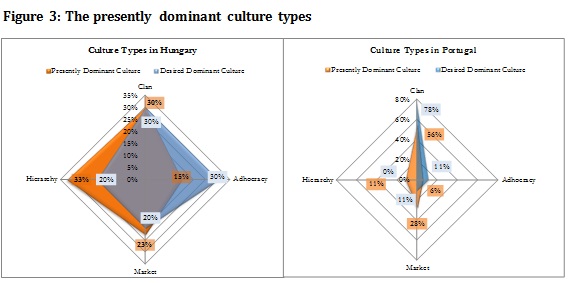

At the beginning of this article we stated that our aim is to compare the Hungarian and Portuguese small and medium sized enterprises in the light of the organizational culture and the transferred leadership roles. In order to examine the relationship between the organizational culture and the transferred leadership roles we have to show the main characteristics of the organizational culture. Figure 3 shows the comparison of the Hungarian and Portuguese organizational culture types by using the Cameron & Quinn framework.

As we see on Figure 3, the respondent Hungarian companies’ dominant culture is hierarchy, but the clan type is also quite dominant. There is a balance between the distributions of culture types among the respondent Hungarian companies. The research sample shows that the Hungarian companies represent all of the 4 culture types. Also we can see that, with time, the desired organizational culture changes in this context. The desired organizational culture is the way companies would like to operate in 5 years’. The Hungarian companies would like to shift toward the adhocracy or stay in clan. The other side of the figure shows the respondent Portuguese companies dominant culture types. It is absolutely clear that the respondent companies operate in a clan culture type, and also the desired culture is the clan. It is also interesting that companies with presently hierarchy culture wish to shift to adhocracy or clan cultures.

The aim of the research is to examine the relationship between the organizational culture types and the transferred leadership roles in Hungary and in Portugal. We showed the dominant leadership roles, and also the present and desired dominant organizational culture types.

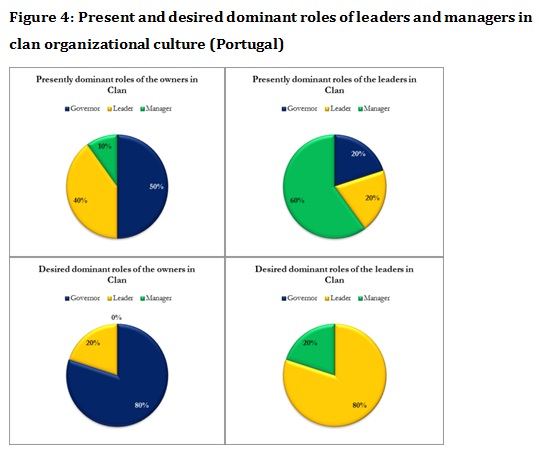

Figure 4 shows the transferred leadership roles in the clan organizational culture in Portugal.

As we can see on Figure 4, the respondent companies’ owners in Portugal would like to transfer all of the managerial tasks, and the leaders want to deal with the leaders’ task, and 20% of the respondents with the managerial tasks. It was expected, because most of the owners would like to deal with the outside communication, such as CSR, and also prefer not to carry the daily operation.

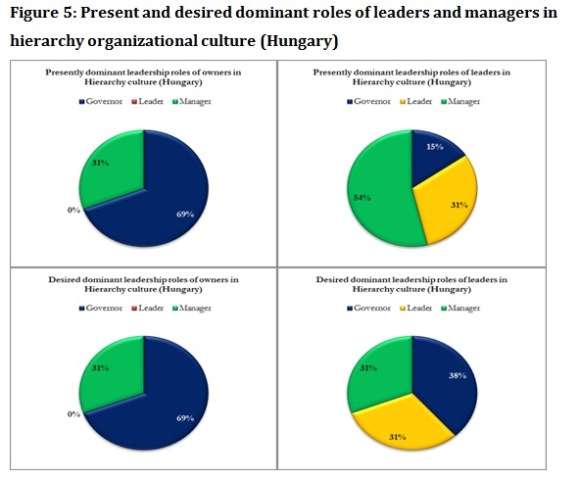

As we can see on Figure 5, in Hungary the respondent companies’ owners mostly deal with the governors’ tasks, and 31 % with the managerial tasks. But it is interesting to note that the desired owners’ tasks do not change. In the hierarchy culture, Hungarian owners would like to deal with the same tasks in the future even if the culture shifts toward the adhocracy. In contrast to Portuguese companies, the Hungarian owners don’t want to give up their managerial tasks. The reasons behind this are maybe that the Hungarian companies have a heavy administrative burden and the owners need a strong control over the daily operation. Additionally, a lot of Hungarian leaders deal with the governors’ tasks, and they would like to increase the number of these tasks in 5 years’ time. And it also should be noted that the Hungarian leaders in the future would like to deal with all of the three roles. We also saw the results in the clan culture type, and in this culture the transferred leadership roles were similar to the hierarchy culture.

We would like to examine the relationship between the transferred leadership roles and the organizational culture considering the Portuguese and the Hungarian results. As we could see, the respondent Portuguese companies’ owners mostly deal with the governors’ and leaders’ tasks and the Portuguese leaders with the managerial and leaders’ tasks. The Hungarian results show that the owners mostly deal with the governors’ and managerial tasks, and the leaders with the governors’ tasks. It is important to note that whilst the Portuguese companies’ owners would like to transfer the managerial tasks, the Hungarian owners barely want to hold the managerial tasks, and do not want to handle the leaders’ tasks.

5. Conclusion

This is a work in progress research and, even with partial results, they allow some speculation and inferences. First, it is interesting to note that the hierarchical culture predominates in the processing industries of Hungary while in Portugal there is mainly a clan culture and both countries wish to operate in clan organizational culture in the coming 5 years, suggesting the existence of companies characterized by traces of freedom and flexibility, with both internal and external focus. Less frequent are the industries with features that focus on processes, control and stability. Such aspects contribute to an overview of the styles of business companies.

Second, it is important to note that companies have, while organizations, quite simple dimensions and structures. Considering that most of the companies studied are family businesses, it is expected that the influence of the founders, entrepreneurs and owners is heavy. In fact, Block (2003) identified that the higher the “organizational distance” between leader and subordinate, as in the case of multiplication of hierarchical levels and functional areas, the weaker the influence of leadership over the culture.

It’s expected that the presence of the owners is a central element in the construction and maintenance of culture of these companies, through business management practices, actions of management people, practices recognition, interpersonal relationships, construction of the vision, strengthening of values, implementation of rituals and other elements related to crystallization of culture. In function of this proximity, it can be speculated that the style of leadership is an intervening element on the characteristics of the culture, whether it be clan, adhocracy, market or hierarchical type. The bibliography suggests that there is influence of leadership in culture (Trice; Beyer, 1991; Schein, 1992), although it can also be the influence of culture on the leader (House, 2004). Anyway, the family business contexts present in this study, either in Hungary or in Portugal, are conducive to fortify clan type cultures.

Third, by observation of the statistical data obtained, the Hungarian company owners did not deal with the leaders’ tasks, and about the distribution of the dominant roles of the leaders, we can see that these leaders are competent mostly in the governors’ tasks, and in equal parts, of the study companies’ leaders deal with the tasks of the leader and manager. Such characteristics are consistent with the conclusions of the work of Masood, Dani, Burns & Backhouse (2006) they found that leadership not transformational prefer to act in the cultures of the market or hierarchical, case of Hungary.

There is a relationship of mutual influence between leader and subordinates, taking into consideration the needs of both sides. The leader spends much of his time talking with his followers to learn more about your goals and problems. Leaders and followers go beyond their own interests or individual rewards towards the good of the team and the Organization, characteristics of transformational leadership, who prefer clan and adhocracy types of cultures, because they are more exposed to variations and demand more performances of situational leadership than in situations of greater control, stability and predictability (as in hierarchical cultures and market) – case of Portugal.

On the other hand, as referred to in House (2004), the Organization's culture and practices influence the attributes and the adopted behaviors and encouraged leadership, the opposite is valid too. In addition, a given culture transfers certain “implicit theories of leadership”, leading to acceptance and effectiveness of leader. This kind of dynamic makes unlikely the isolation of independent variables (leadership or culture), because it suggests a simultaneous and dynamic construction.

The concepts and relationships presented in this article - involving the cultural typology of Cameron & Quinn and transformational/transactional leadership - can bring contributions and insights for the actors involved in businesses, making clear the cultural characteristics and leadership of a given region, enabling reflections on its implications. In the context here explored, the hierarchical and the clan cultures were prevalent. Do they suit the targeted policies and strategies for the development of companies in the study? It is possible that such strategic guiding and environmental factors (competition, changes in customer profiles, new international incoming or with higher degree of professionalization, etc.) can guide efforts and local initiatives through alignment of people management practices (such as the selection and training of managers) and the development of consistent leadership and with cultures that would be more interesting to strengthen a particular business sector.

According to the results, it’s possible to infer that some cultural values can be influenced by some components of leadership performed by leaders. However, few associations were found between the two constructs in the study. We will further develop our research to delve into this issue.

It’s important to note that both the type of culture as the kind of leadership emerged of perceptions of the same respondents; this aspect may have made a little clearer the differentiation between “what is” and “what could be” (House, 2004) and can also evidence more individualized than group “implicit theories”. In this way, it would be interesting, in the continuity of this study, to include other respondents, other actors involved with the operations of companies. Also triangulation procedures (involving qualitative methods, on-the-spot observations, interviews, etc.), could promote a richer understanding, with more nuances, contributing to the clarification of the interactions between the concepts studied. As a form of continuity, we also suggest the replication in other regions of other countries, in order to enlarge the sample size and, at the same time, the comparative analyses. In addition, it could or this could be made in future relations with dimensions such as performance, service quality and innovation. Finally, the analysis considering social culture, historical and environmental pressures on companies studied could clarify the elements relevant to the understanding of these concepts and their relationships.

References

Bass, B. M. & Stogdill, R. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill's handbook of leadership theory, research, and managerial applications. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Bateman, T. S. & Snell S. A. (1999). Management: Building a Competitive Advantage. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Bennis, W. (1989). On becoming a leader. Reading, Mass: Perseus. [ Links ]

Bennis, W. & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders. The Strategies for Taking Charge. New York: Harper Perennial. [ Links ]

Berg D.N & Smith, K. K. (1990): Paradox and Groups. In J. Gillette & M. McCollom (Eds.), Groups in Context: Advancing the Group Dynamics Tradition (pp. 106-132). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Block, L. (2003). The leadership-culture connection: an exploratory investigation. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 24(6), 318-334. [ Links ]

Brady, G. F. & Helmich, D. L. (1984). Executive succession: Toward excellence in corporate leadership. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Cameron, K. S. & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: based on the competing values framework. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Cannella A., & Shen W. (2001). So close and yet so far: Promotion versus exit for CEO heirs apparent. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 252–270. [ Links ]

Capowski, G. (1994). Anatomy of a leader: where are the leader of tomorrow? Management Review, Vol. 83(3), 10-18. [ Links ]

Covey, S., Merrill, A. & Merrill, R. (1994). First things first: To live, to love, to learn, to leave a legacy. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Daft, R. (2003). Management. London: Dryden. [ Links ]

Davis, K. (1967). Human Relations At Work: The Dynamics Of Organizational Behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Dover, P. & Dierk, U. (2010). The ambidextrous organization: integrating managers, entrepreneurs and leaders. Journal of Business Strategy, 31(5), 49-58. [ Links ]

Európai Közösségek Bizottság (2008): Soroljuk a kkv-ket első helyre! Európa jó a kkv-k számára és a kkv-k jók Európa számára. Luxembourg: Európai Kiadóhivatal. [ Links ]

Fizel, J. & D’itri, M. (1997). Managerial efficiency, managerial succession, and organizational performance. Managerial and Decision Economics,18(4), 295-308. [ Links ]

Friedman, S. & Singh H. (1989). CEO succession and stockholder reaction: The influence of organizational context and event content. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 718–744. [ Links ]

Giambatista, R. & Rowe, W. (2005). Nothing succeeds like succession: A critical review of leader succession literature since 1994. Leadership Quarterly, 16(6), 963–991. [ Links ]

Haddadj, S. (2006). Paradoxical process in the organizational change of the CEO succession, A case study from France. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 19(4), 447-456. [ Links ]

Haveman, H. (1993). Ghosts of managers past: Managerial succession and organizational mortality. Academy of Management Journal, 36(4), 864-881. [ Links ]

Hay, A. & Hodgkinson, M. (2006). Rethinking leadership: a way forward for teaching leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(2), 144-158. [ Links ]

House, R. J. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of sixty-two societies. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. [ Links ]

Kesner, I. & Sebora, T. (1994). Executive succession: Past, present and future. Journal of Management, 20, 327– 372. [ Links ]

Kotter, J. (1996). Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

Kreitner, R. & Kinicki, A. (2004): Organizational Behavior. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [ Links ]

Levitt, T. (1976). The industrialization of service. Harvard Business Review, 54(5), 63–74. [ Links ]

Maccoby, M. (2000). Understanding the difference between management and leadership. Research Technology Management, 43(1), 57–59. [ Links ]

Masood, S., Dani S., Burns, N. & Backhouse, C. (2006). Transformational leadership and organizational culture: the situational strength perspective. Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 220(6), 941-949. [ Links ]

Perloff, R. (2004). Managing and leading: The universal importance of, and differentiation between, two essential functions. Reston: American Society of Civil Engineers. [ Links ]

Plunkett, W. R.(1996). Supervision: Diversity and Teams in the Workplace. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Quinn, R. E. & Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public Productivity Review, 5(2), 122–140. [ Links ]

Riggs, Donald E. (Ed.) (1982). Library Leadership: Visualizing the Future. Phoenix, Arizona: The Oryx Press. [ Links ]

Rowe, W. G., Cannella A. A., Rankin, D., & Gorman, D. (2005): Leader succession and organizational performance: Integrating the commonsense, ritual scapegoating, and vicious-circle succession theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(2), 197– 219. [ Links ]

Schein, E. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Stogdill. R. M. (1997). Leadership, Membership, and Organization. In Grint, K. (Ed.), Leadership. Classical, Contemporary, and Critical Approaches (pp. 112-124). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Storey, D. (1994). Understanding the Small Business Sector. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Trice, H. & Beyer, J. (1991). Cultural leadership in organizations. Organization Science, 2(2), 149- 169. [ Links ]

Watson, C. M. (1983). Leadership, management and the seven keys. Business Horizons, March-April 1983, 8-13. [ Links ]

Weathersby, G. B. (1999). Leadership versus management. Management Review, 88(3), 5. [ Links ]

Wheeler, M. E. (2008). The leadership succession process in megachurches. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Temple, 2008). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/33/20/3320074.html. [ Links ]

White, M. C., Smith, M., & Barnett, T. (1997): CEO succession: Overcoming forces of inertia. Human Relations, 50(7), 805–828. [ Links ]

Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson-Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Zaleznik, A. (1977). Managers and leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review, 55(3), 67–78. [ Links ]

Article history

Submitted: 28 June 2012

Accepted: 17 November 2012